|

Did you know that olive oil is the only common cooking oil that is the juice of a fruit? All the other oils we use in our kitchen come from seeds: sunflower, rapeseed (canola), peanut and grapeseed. This realisation leads directly to another question. Would you cut an orange, leave it on the counter for a week and then squeeze and drink the juice? Would you step on an apple, leave it on the table for three days and then eat it? Yet that’s what happens to many olives before they’re pressed to extract olive juice. I’ve tasted and written a lot about olive oil, but this idea had completely escaped me until I met Elisabetta Sebastio last year. She’s a professional olive oil taster both for Italian Chambers of Commerce and international olive oil competitions. We ran our first full-day olive oil class during my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November. It was a revelation for all of us.

Learn more on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/olive-juice/

0 Comments

What happened to Janet after indulging in artisan food in Tuscany? Here’s the unexpected answer in my latest post on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/life-changing/ Shortly after she returned home to California I received a WhatsApp message from her which began:

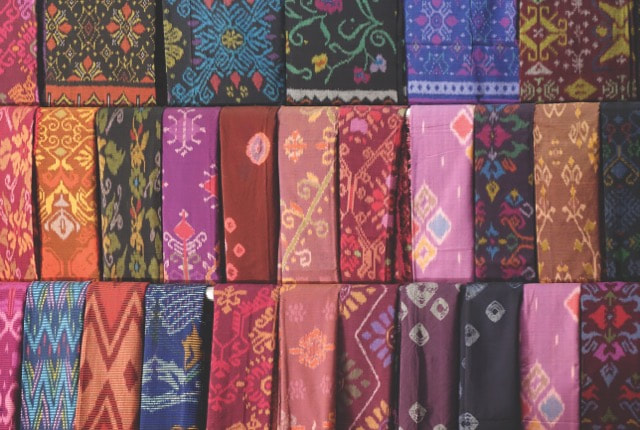

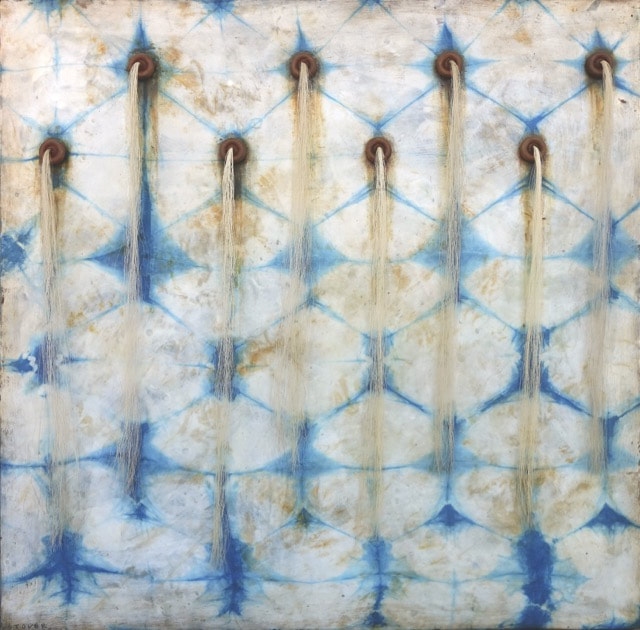

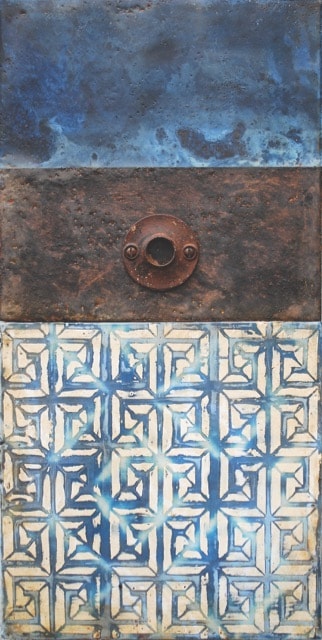

“You have ruined me!!!” I was worried, but not for long. Read the rest of my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/life-changing/ Guest blog by Susan Stover, artist and educator On the eve of the Tastes & Textiles tour, I’m posting Susan Stover’s insights about the power of travel to invigorate one’s creativity. (All photos by Susan Stover.) Travel can greatly impact an artist’s work. It can influence, be a catalyst for change, or further catapult the journey already started. In the absence of familiar surroundings, it can magnify what captures the eye and the emotions. All is new, exciting, and exhilarating. Both making art and traveling have opened up new experiences and challenged me in unique ways. There is so much to be inspired by—the atmosphere in the landscape, hues and textures of a traditional market, shrines and temples, and environments of living and creating. I recently returned from my second trip to Indonesia in the last 15 months. As the experiences and inspirations linger in my subconscious, they continue to influence my artwork. My love of textiles was rekindled as a result of these travels. Fabrics abundantly adorn shrines and temples, are used as offerings, typify ceremonial dress, and are displayed as consumer goods. I am inspired not only by the beauty of the fabrics, but also how they function in a society where art, life, and spirituality are all connected. Nowhere is this more evident than in Bali. Concepts of duality, animism, and the desire for harmony between the natural and supernatural worlds are the foundation of Balinese beliefs. My fascination with the connection of art and spirit lies in the mystery, the unanswered questions, the quest for balance and purpose, the desire for connectedness with others and with the sacred, however they choose to define it. Textiles embody these concerns, which are more evident in cultures other than my own. When traveling, I am conscious of how closely tradition and technology are related. Weaving and dyeing cloth are technologies that have existed for millennia. As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the western world is more removed from these technologies, as most cloth is made in factories. Our direct relationship to the production of fabric and items for survival does not exist. In countries like Indonesia, these traditions are part of cultural identity and there is a sense of pride in the hand making of them. Some of the places in Java and Bali that I visited still produce cloth exactly as it has been done for hundreds of years. The tools and settings of these shops look like they have not changed over the ages, and it was like stepping back in time. It was always surprising to see cell phones in these environments—the juxtaposition of ancient and modern. This is what I am after in my own work—taking something from one arena, bridging the gaps of time and place, and situating it in a new venue. There is an inherent beauty to the handmade, purposed item that looks old and worn. Often I think of history, what or who came before me, what was left behind, and how we are joined to others by the same activities that keep our hands busy. The rhythmic beating of a loom and the repetitive movements of stitching and stamping can be meditative and calming. There is a satisfaction to this type of labor. Textiles imply an association with human touch and human interaction and I am curious how the maker’s role functions individually and collectively in a community. What interests me is the information that textiles contain, as patterns and techniques encode knowledge from ancestors and tell us much about a culture’s cosmology and development. Perhaps it is my own desire for connection to the larger world that drives me to seek out authentic artisans working in methods that have been handed down from one generation to another. Throughout the years, my work has incorporated the combination of textiles and painting. I have worked in many ways using dye, paint, thread, fabric, and fiber. Prior to traveling to Indonesia, I had been using surface design techniques on silk and embedding them into encaustic to develop my own visual language of unique mark-making and patterning. A shift happened in the work as a result of traveling—the fabric itself became the subject matter and a springboard for new content. I wanted to make work that looked like old cloths that were worn in a way that would suggest some sort of use or purpose. They could be fragments or relics and could incorporate techniques typically found in ritual textiles and costumes. Recently, I have been combining surface design techniques (such as discharge, silk painting, and indigo dyeing) on silk with encaustic on panel. There is marvelous allure of adding color to cloth and a magical alchemy of dyeing with indigo. When layering the silk into encaustic, the wax is beautifully absorbed by the silk. The silk then becomes semi-transparent, revealing rich subtleties of colored wax underneath. Murky layers of wax on top of the silk can add depth, mystery, and freeze the fabric in the moment. Working with encaustic in many ways is like working with fiber. There is a tactile quality to the wax that makes one want to touch it. The translucent layers of wax are similar to working with layers of dye. Wax can reflect and absorb light like various fibers. There are the textural and sculptural capabilities of wax as there are with fibers. When I started thinking of my “paintings” as “objects,” it stimulated ideas of working sculpturally and freed me from thinking within the confines of the panel. It opened up the possibilities of working with other fibers, materials, and techniques. Incorporating these materials and working in this way, my intention is to create artwork that evokes a sense of transcendent mystery and purpose. The goal is to imbue the work with a vulnerability and vitality that reflects the presence of the maker. Each piece is a personal meditation on what connects the past and present, the beauty of imperfection and age. The challenge is how to make the things that inspire me and at the same time place them in a contemporary context. How do I celebrate these inspirations, use these traditions, and express it in a way that is relative to my own culture? As I travel and seek inspiration, I am aware of how tourism and commercialism affect these places. Traditional weaving patterns can be found printed cheaply on cotton fabric. ”Fake” batiks are abundant. Natural dyes and materials are often replaced by cheaper synthetic ones. Symbolic meanings are in danger of being lost as techniques and knowledge may not be handed down to future generations. I believe that it is important to recognize the value and conservation of traditions and cultures with awareness and mindfulness of our impact on them. Threads of Life and the Bebali Foundation in Ubud, Bali, seek to preserve and restore indigenous textile cultures in Indonesia. They work with women’s weaving cooperatives to help manage their resources sustainably and relieve poverty in remote areas. The Bebali Foundation does botanical research of natural dyes and mordants. I spent a wonderful afternoon in the Bebali Natural Dye Garden dyeing with the indigo that is grown there. The garden beds are filled with different varieties of indigo and plants for other colors and mordants. My consciousness and respect has grown for the beauty existing in other parts of the world as a result of my travels. I am grateful for the rich heritages that endure and am optimistic of how they might evolve. I am looking forward to future art inspiring journeys in Italy, India and a return to Java with others who share a similar interest in appreciating the artistry of cultural traditions.

Susan Stover teaches and shows her work nationally and internationally and maintains a full time studio practice in Graton, CA: www.susanstover.com. This article first appeared in the Surface Design Journal Winter 2015/2016 “Wax & Fiber” issue, Volume 39, Number 4. The Journal is available in single print issues for purchase at: www.surfacedesign.org/marketplace . A subscription to the quarterly Surface Design Journal is just one of many enriching textile-arts and education benefits enjoyed by members of Surface Design Association, which will celebrate its 40th anniversary next year. Members receive the beautiful print publication 4 times a year along with access to all of our digital editions (published since the Spring 2015 “Warp Speed” issue, Volume 39, Number 2). www.surfacedesign.org/subpage/digital-edition-now-available Feasting is a way of celebrating special events, and many festivals have acquired a constellation of typical dishes. Often these are elaborations of everyday food, tarted up for the occasion. In many parts of Italy (maybe all, but I haven’t been everywhere) no meal is complete without bread, so what better food to make a fuss of. The Garfagnana has its own special Easter bread called pasimata. Paolo Magazzini, the village baker at Petrognola to whom I take my guests for bread lessons, recounted his procedure, the lengthy traditional way. You take flour, sugar, butter, eggs, milk and lievito madre (starter dough). Day 1 morning: mix all ingredients. 12 hours later: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. Day 2 morning: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. 12 hours later: add sultanas, aniseed, vin santo (sweet Tuscan dessert wine), chestnut-flavoured liqueur. Day 3 morning: light wood-fired oven. Bake a batch of bread. Put pasimata dough in round tins. After one hour, take bread out. Oven will be exactly the right temperature for pasimata. Bake pasimata for 40 minutes. Remove from oven and eat enthusiastically. The long rise over 48 hours allows time for the development of exceptional flavours and aromas. Today many people make a ‘fast cake’ version in an hour by substituting baking powder for sourdough starter. Next Easter I’m going to organise a blind tasting of the slow and fast versions.

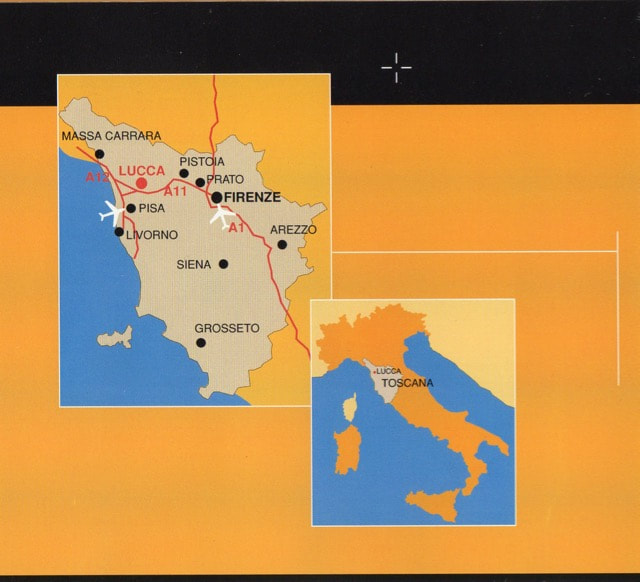

I didn’t ask Paolo for the quantity of each ingredient, since I can get my fix from him. For those not so lucky, here’s a similar recipe from Castiglione in Garfagnana, a walled town which during the Renaissance was batted back and forth like a ping-pong ball between Lucca and Modena. Perhaps they consoled themselves between battles by eating pasimata. My Tuscany isn’t the manicured cypress-lined lanes of Siena and Chianti. It isn’t the great art and architecture of Florence. My Tuscany is Lucca in the northwestern part of the region. As enchanting and perfectly formed as the city of Lucca is, it isn’t my Tuscany either. My Tuscany is the Piana di Lucca, the flat plains and low hills surrounding the city. My Tuscany is Versilia, the coastal plain to the west of the city. My Tuscany is the Media Valle del Serchio and the Garfagnana, the mountains and the Serchio River valley to the north of the city. This is the territory you come to for your adventures with Sapori e Saperi (‘flavours and knowledge’). Some friends have made four short films capturing the essence of my Tuscany. Although they call it Part 2, I’m dishing up Lucca first. If you’ve been on the cheese course (Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/), you’ll recognise Monica Ferrucci and her goat cheese. Or, your feet might have helped Gabriele da Prato crush his grapes. Maybe you’ve attended the Disfida della Zuppa (Soup Tournament) and helped judge the zuppa alla frantoiana entries (read more about the Disfida here: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/better-than-the-winter-olympics/). Or did you pick and press olives with me. If not, treat yourself to my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November (http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/small_group_tours/autumn-in-tuscany/). You’ll have a crash course in olives and their oil, you’ll also hunt for white truffles (and eat them) and, best of all, you’ll get to know a little bit of my irresistible Lucca.

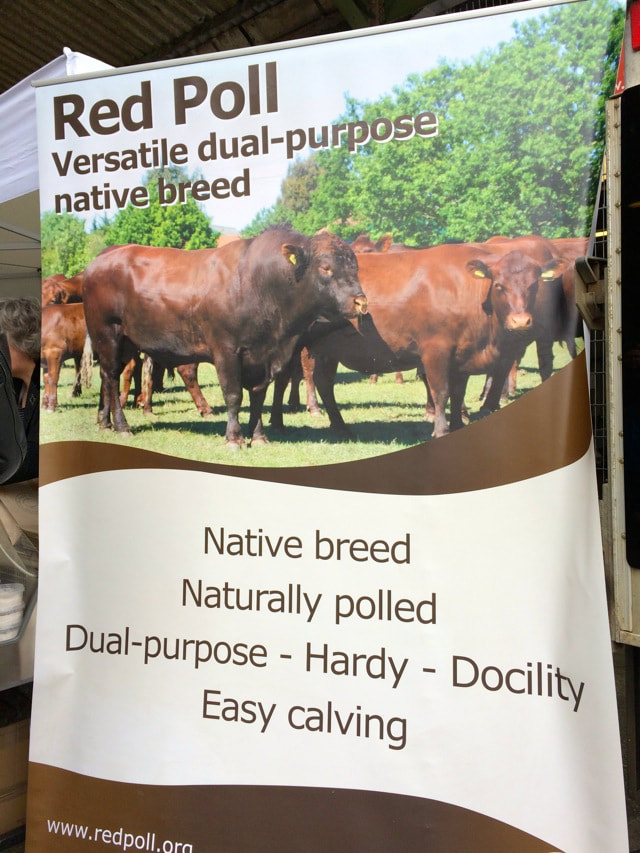

At the end of my Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I organise a little game: an England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament. This entails a trip back to the UK immediately before the course to go to Neal’s Yard Dairywhere I can always find a few excellent sheep cheeses. For the May course I did my shopping instead at the annual Artisan Cheese Fair at the old Cattle Market in Melton Mowbray. Although in its fifth year, I had never heard of it, but being featured by the Specialist Cheesemakers Association, I figured it would be worth the trip to Leicestershire, a direct train journey from Cambridge on the line to Birmingham, from where my friend Amanda joined me. It’s also one of the counties, along with Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, in which Stilton is allowed to be made. (Stilton, like Parmigiano Reggiano, is a registered product with a Protected Designation of Origin.) Unlike the market in Cambridge, which is today a ‘cattle market’ in name only, the one at Melton Mowbray still functions every Tuesday morning. I make a resolution to come back to witness the livestock auction. Turning to the entrance to the cheese fair opposite, we find the entrance fee is only £2 and admits you not only to the area populated with vendors’ stalls, but also to a series of cheese classes and tastings. The Red Poll Cattle Society was founded with the aim of preserving this versatile native breed. They note the long lactation period and ideal composition of the milk for cheesemaking. The British Isles are a land of cattle. Sheep these days are reared for meat, and it’s harder than I expected to find sheep’s milk cheese. These people from Canterbury can’t offer any. Amanda has served me excellent goat’s milk cheeses made by Pete Humphries of White Lake Cheeses in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, heart of cheddar country. At the far end of his stall, I glimpse a label saying ‘No Name Sheep Cheese’. He’s begun experimenting with sheep’s milk and this cheese is so new that he hasn’t come up with a name yet. It’s a bit young to compete with the mature pecorinos in the Italian team, but I hope it will make up in youthful energy for what it lacks in experience. Sharing a corner stall are two outstanding talents of British cheese, Jamie Montgomery who makes arguably the best cheddar in Britain, and Joe Schneider who makes Stichelton. Amanda and I found the farm on the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire for Joe and Randolph Hodgson of Neal’s Yard Dairy when they were setting up the dairy to produce what they expected to call ‘raw milk Stilton’, a return to how Stilton was made for centuries. However, due to an anomaly in the PDO definition of Stilton, it can only be made with pasteurised milk. One of the Dairy’s customers suggested Stichelton, an early name for the village of Stilton. Joe welcomed us to the stall and gave us a good chunk of this incomparable cheese to take home. Notice in the photo that the Stichelton isn’t excessively blue. The flavour of the blue mould doesn’t kill the flavour of the cheese. In search of two more sheep cheeses we crossed to another pavilion, passing a ukulele band and an artful display of Quickes Traditional Cheddar. Right at the entrance was the stall I needed. Carlow Farmhouse Cheese had brought several mature sheep’s milk cheeses to the fair. They don’t have their own website, and this one only admits to cow’s milk cheese. Their cheesemaker, Nadja, guided us through her samples. It was hard to choose, but I finally took some ‘pecorino-style’ and ‘cheddar-style’. Business done, we threaded our way through the crowds to a promising-looking pork pie stall. The pies were obviously raised by hand. The pastry is made by mixing hot melted lard with flour. It has to be exactly the right temperature to form it around the wooden moulds (see photo above)—not so hot that it burns your hands and not so cold that it cracks. The baker himself sells us our pie. He reminds me of my Italian artisan food producers when he talks about the natural ingredients he uses: the flour from a nearby windmill, pigs from a local farm and pig’s-foot jelly he makes himself. He’s sold 300 pies this morning and will be off soon to make another 300 for the next day’s fair. With a glass of incredibly strong cider, we settle down to lunch. I used to make pork pies myself, but these pies beat even my best. The crust was crunchy, the filling tasted like pork (not overpowered by spices and preservatives) and the jelly was well seasoned and firm without being rubbery. Melton Mowbray is a pretty market town, but even without its other attractions, it would be worth a pilgrimage for the King’s Road Bakery pork pies alone.

Italy is usually the clear winner of the pecorino match, but this time Ireland came out top in the opinion of our maestro Giancarlo Russo, a judge in international cheese competitions. Young ‘No Name’ was a big hit too with several of the course participants. A guest blog by Bob Schroeder Bob, his brother Dick and their friend Cullen Case came on my Advanced Salumi Course. They wanted to make the most of their visit and signed up for a truffle hunt on the Tuesday afternoon after the extension workshop. Bob gave me permission to republish his enthusiastic report to his family and friends back in the States. January 20, 2015 We went truffle hunting today. Lots of fun. Our guide actually trains dogs. He took Guy Fieri of Food Network fame on a hunt. Thanks, Bob!

In case you don’t know, truffles can be found all year long. Although the white Italian and black Périgord truffles are the stars, they’re all good and well worth tasting. We have seven edible ones in Tuscany. After the hunt, we go back to Riccardo’s home for a truffle feast cooked by his wife Amanda. We sit in their kitchen sipping prosecco with the antipasti and get to be part of the family. ‘Garfagnana Dove Il Tempo Non Corre’ is the motto printed on aprons sold by the tourist office in Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. It means literally, ‘Garfagnana where time doesn’t run’. We might say, ‘where time stands still’. In fact, it creeps along slowly. I’ve just reread a piece by Rebecca Solnit in the London Review of Books (29 August 2013) in which she reflects on some of the effects our electronic age have had on our experience of time: the interruptions to our concentration, the fragmentation of our solitude and relationships. She wonders how far we will allow big corporations to shatter our lives. Will we all be wearing Google glasses with continuous pop-up messages reminding us of practicalities while causing us to forget to ‘contemplate the essential mysteries of the universe and the oneness of things’? Then she muses: ‘I wonder sometimes if there will be a revolt against the quality of time the new technologies have brought us… Or perhaps there already has been, in a small, quiet way. The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn’t food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn’t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes and labour, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken.’ Reading this I realise it’s that wholeness I see in the producers to whom I take my clients: an immersion and satisfaction in what they do. It’s not that they don’t have to work hard or that they don’t have troubles, but that doing something from start to finish, from sowing to harvest, from slaughter to salami, from fibre to fabric, for themselves, their families and their communities produces a contentment way beyond the monetary value of their work. I can think of so many examples it’s hard to know where to start or stop. …in a wood-fired oven he built himself heated with wood he chopped himself. He didn’t grow the wheat, but he does grow farro and corn. The farm is an agriturismo which he and his wife Cinzia run. And he has a bar a short walk from the farm. Paolo Magazzini is another unhurried multi-tasker. He’s a farro and beef cattle farmer. He fertilises his fields with the manure of the cattle. He ploughs, plants with his own seed corn, harvests and pearls the farro. He provides the pearling service for about a dozen other farmers. Paolo is also the village baker, carrying on his mother’s trade. His recipe includes his farro flour and his own potatoes. From her smile, I wonder if she’s thinking about the beautiful finished articles he weaves. Schoolchildren come to her workshop to learn about the history of their families and Lucca in the silk trade. Gino will carry the business forward with a smile into the next generation. What more could any parent hope for? …in his forge powered only by water. It takes considerable inner fortitude to resist the health and safety inspectors who want her to use stainless steel. Andrea is never short of time when he can spend it with customers who he feeds with his latest artisan food finds. He dreams up new recipes when he comes to check his beer in the middle of the night. …and the long hours he spends in the woods with his dog infuse his family and work life too. The wholeness of my producers’ lives floods over to envelop my driver Andrea Paganelli and me.

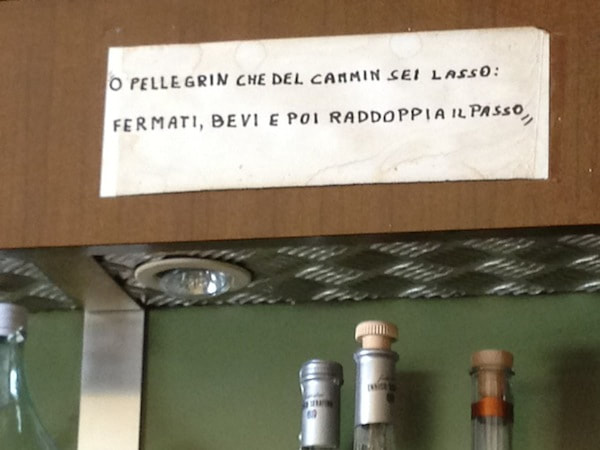

A couple of Thursday evenings ago I wrote a to-do list for Friday. The first item on the list was to pick up some leaflets at Topo Gigio, the bar-trattoria in Fabbriche di Casabasciana, the village at the bottom of my hill. The leaflets advertised a concert on Sunday for the benefit of the centre for the elderly at Casabasciana, which I was helping to organise. Considering the length of my list, all the things I wanted to get done before the weekend, the sensible thing would have been to hop in my car and drive the 3.8 km (2.4 mi). But it was a warm, not too hot, sunny day, and I hadn’t walked the mulattiera in ages. People in the village used to walk down it to school or work and back up again at lunch time every day. It seemed a bit feeble not to do it. I strapped my pennato lucchese, a Lucca-style billhook, around my waist and invited my friend Penny to accompany me with her secateurs. Mulattiera translates as ‘mule track’, but this makes it sound a paltry dirt path. In fact, the mulattiere (plural) were the super highways of the past, often many metres wide, surfaced in rounded cobbles or flat paving slabs, with stone-lined drainage channels at the sides or down the centre. Where necessary they were stepped. In mountainous areas like mine, they ran along ridges, usually just below the crest. Although they frequently crossed streams and small rivers, it was at the top where the water course was narrow and presented no great obstacle even in the rainy season. They descended to the valleys of major rivers only where absolutely necessary to arrive at a destination on the other side of the river. I’m not sure how old the roads in the Garfagnana are. It’s known that the Roman Consul M Claudio Marcello had the Via Claudia or Clodia Nova built in the 2nd century AD, and it’s likely that it followed an Etruscan road and possibly even earlier routes. The mulattiera that links Casabasciana with the valley is said to be mediaeval, but that’s the date people always attach to anything old. It’s about 4 metres wide and forms the main street in the village, descends about 100 m below the village and splits in two, the left fork diving steeply down to the pieve, the old romanesque parish church, and then continues to Sala, a hamlet of about 15 houses, which is linked by another mulattiera to the Liegora River which runs into the Lima River to the right. The other branch carries on straight down to the Lima, along which Fabbriche di Casabasciana is strung out. I’ve learned from my neighbours that upkeep of the mulattiera was the responsibility of each family through whose property it passed. In the ’60s the present-day car road was built, and since then the mulattiera has been used less and less by the locals. Only the sections used by woodsmen, hunters of wild mushrooms and wild boar, and horse riders (mostly tourists) are now maintained, and even these denizens of the forest tend to favour newer dirt roads suitable for 4×4 vehicles. It’s to us stranieri, who arrive with the notion of nature as a setting for recreation instead of work, that the task of cleaning the mulattiere now falls. Penny and I set off at about 9.30. We hacked, slashed and clipped our way to the bottom by around noon. Some parts of the road had been cleared but others were thick with elder and acacia saplings intertwined with clematis (old man’s beard) and brambles. It was particularly galling to find that one household had cut their land down to within a metre of the mulattiera and hadn’t been civic-minded enough to cut that stretch of the mulattiera as well. At Topo Gigio, arms scratched and bleeding, we bragged about our feat to the men playing cards or arriving for lunch, and taunted them by asking where they had been when needed. ‘O pilgrim, weary of your journey: stop, drink and then redouble your pace.’ Restored by the excellent worker’s lunch, I collected the leaflets and we set off back up the mulattiera. Even though uphill, it was much easier going this time.

If anyone knows of a volunteer work group skilled at repairing cobbled roads, please get in touch with me at info@sapori-e-saperi.com. They’ll receive warm hospitality at Casabasciana. Participants on the Advanced Salumi Course work with three norcini (specialist pork butchers) in three different parts of Tuscany. Recipes and methods change every 20 km, depending on regional variations and family traditions. If people stay for the extension workshop, they experience a fourth point of view with another family. They learn to make authentic Tuscan salami, prosciutto, and several other air-dried and cooked pork products. One of the lesser known of these are ciccioli, or grassetti as they’re called in the Garfagnana. Grassetti are the crispy residue of producing lard, much used in the past for frying and baking, especially in mountainous areas at altitudes where olive trees are less well adapted than the pig. The process entails cutting pork back fat (without the skin) into cubes… …and rendering it over a low heat until the pieces are brown. Then the pieces of hot fat are put in a press to squeeze out as much liquid fat as possible. The resulting pork chips are salted and drained on absorbent paper. They’re more addictive than salted peanuts, and chefs who attend the course realise immediately their potential as bar snacks. Gina Piazza (whose husband Kirby Piazza took most of the photos in last week’s blog ‘Like the Seasons: the Life of a Cheesemaker’) came on the course in March and sent me this report in early June: We had a press made by a welder friend and from 2 pounds of back fat we came up with a handful of ciccioli—but they’re amazing and I did it just as Ismaele makes it. I have 12 pounds of fat on order so maybe next batch will yield at least a few pounds. Now I have tons of rendered fat! The Advanced Salumi Courses for winter 2014–15 are almost full with one place left on the November course and three places on the February course. For more details of the course see Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed