|

By Alison Goldberger March, what a month it’s been for us all! We went from looking forward to a month filled with courses to living under a lock-down. Who could have expected what was to unfold? However, we were extremely lucky to have two talented students join us on the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany at the beginning of the month just when the coronavirus came to northern Italy and we all still hoped it could be contained. The course was fully booked but travel restrictions and strict government rules were already starting to be put in place meaning some of our participants didn’t make it. We welcomed Seamus Platt who is head chef at The Shambles in Seattle and sources all his ingredients locally. I was particularly interested to hear his pigs come from a small farm that has a variety of old breeds. Katie Krauss is an ex-chef who now produces her own premium distilled vodka and dry gin in Australia. She’s also teaches salumi making. An interesting pair! Below are some of our favourite photos from the course. As soon as the students were dropped off at the station Erica had to quickly negotiate the realities of the new coronavirus lock-down. One unexpected problem was trying to get a friend’s car out of an airport car park before it closed down. While they were stuck in England Erica had to rescue the car…without breaking the strict new rules. Read all about it in her blog post. Now it’s the little things that keep us all going! Erica has been enjoying cooking some delicious, and seasonal meals. Such as castagnaccio made from chestnut flour. It’s a real comfort food but naturally sweet and with no added sugar. It’s made from chestnut flour, a little extra-virgin olive oil, grated orange rind, water and topped with walnuts and rosemary. Best hot from the oven! The woman who owns her village shop has also been baking colombine (literally ‘little doves’) early as a treat for the locals! It’s usually eaten at Easter and is a yeasted bread dough with just a little sugar and butter – it should be neither sweet nor savoury so it can be eaten with either jam or salumi. Above you’ll see a photo from a beautiful walk she took along the mulattiera from her village to the hamlet of Corona (a complete coincidence!) – she wrote about it for Slow Travel Tours here. It’s definitely not an easy time for small businesses but we are looking forward to welcoming you back to Italy soon to share the knowledge of our artisans and show you the most beautiful, off the beaten track parts of this fantastic country.

If you have any questions about future tours, please get in touch with Erica at [email protected]. We wish you all good health!

0 Comments

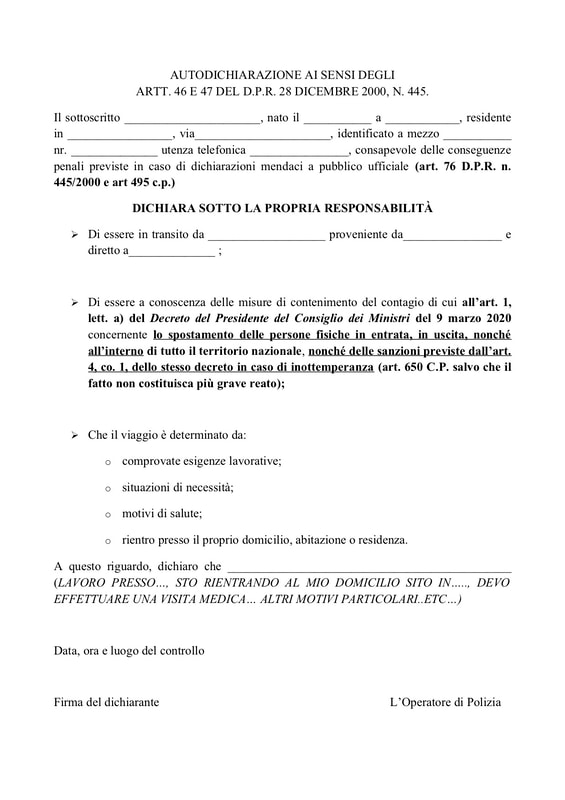

When they issued the country-wide community containment decree for coronavirus on the evening of Monday 9 March, I’m sure the last thing the Italian government had in mind was K&P’s car. My English friends had left it in the care of Europark, an excellent, inexpensive private car park five minutes’ walk from the terminal at Pisa Airport. K&P were in England, planning to return on 23 March. On the morning of Thursday 12 March I received a panicky email from P. Their flight had been cancelled; they didn’t know when they would be able to get back. What would happen to their car? When I phoned Europark, they were panicky too. They had been ordered to close as soon as possible. Their terms guarantee that the car park will be under video surveillance 24-hours a day. If they closed, they wouldn’t be able to fulfil this condition. They had to empty the car park by Saturday morning. Everyone except K&P had either managed to get back earlier to pick up their cars or would be back before Saturday. K&P’s car was the only one that would be left. We had to get it out. But how? I read the whole decree in Italian. It contained much interesting information and caring thoughts for Italian citizens, but nothing about cars marooned in car parks. The only conditions under which an individual was allowed to move from his or her home were:

For whichever reason you were travelling, you had to carry with you a self-declaration of the purpose of your journey. The penalty for not having one or lying was either three months in prison or a fine of 206 Euros. Already two people from Lucca had been checked by the police and fined. First brilliant idea: Maybe it was within the scope of my driver’s ‘proven need to work’. He could go with a colleague and drive the car up to me. He didn’t think so. His work is providing the public service of driving people from A to B, not driving someone else’s car. Second brilliant idea: Maybe we could find a car bodywork garage with a tow truck who would go get it. Surely it was within their ‘proven need to work’. My driver would phone his mate to find out whether he could do it and how much it would cost. He would also ask the police whether he himself could do the job under the terms of the decree. By now it was late Thursday afternoon, and they wouldn’t be open until Friday morning. Meanwhile, I was emailing P and phoning Europark to make sure nothing had changed there and to find out what they needed from K&P to release the car to someone else. P was also organising with neighbours down the hill to park the car at their house where they could keep an eye on it. On Friday morning my driver confirmed that his friend could pick up the car. It would cost a goodly sum, but at least the car would be free. The police had said it wasn’t within their authority to state whether my driver could do the job or not. I phoned the bodywork garage. They were busy all day Friday. They could go on Saturday. I phoned Europark. By Saturday they would be closed. Third brilliant idea: I phoned my car mechanic. If I ran an artisan car repair course, Roberto would be my man. He understood the problem immediately. He would ring his friend Stefano, who has a car roadside rescue business near Lucca. I could phone Stefano in five minutes. Stefano turned out to be the white knight of this saga. He could be at Europark at 3 pm with his low loader. What make of car was he to pick up? Me and cars. I’d ridden in the car, but had no idea. I remembered K&P talking about wanting a Jimmy, so that’s what I said. I needed the name of Stefano’s company for P’s email to Europark. Stefano pronounced it, and I heard what sounded like Boodado e Terrenche. It took some inventive searching on Google to find Bud e Terence. It seems that to liberate a car, you have to be an aficionado of Italian films. Of course I know many of the classics, but I’d never heard of this thin and corpulent duo who were starring in films from the ‘60s to the ‘80s, nor of the Bud & Terence film festival at Masone in Ligura. I sent the wording of the email for Europark to P, leaving blanks for the model of car and the registration number. She copied me into the email to Europark, but I didn’t read it. At 2.58 pm, Stefano rang me. He was at Europark, but the car they had given him wasn’t a Jimmy. Uh, oh. I checked P’s email. Sure enough, it wasn’t a Jimmy. It was a Diahatsu Terios. Stefano would be here in an ‘oretta’ (this should mean a ‘little hour’, but in fact means a little over an hour). He’d phone me from Topo Gigio bar and lunch place, a landmark at the bottom of our hill known by everyone for miles around, and I’d drive down to meet him and guide him to A&J’s house. Would the police be checking our tiny winding road? I prepared two self-declarations, one for going shopping at Bagni di Lucca (I could go buy something if necessary) and one for returning home. As it turned out, Stefano was already coming up the road as I headed down. What a hero! If you ever need roadside rescue anywhere in Italy or France (probably other countries too) — when we’re allowed to travel — give him a ring (+39 339 6239872). By Alison Goldberger In February we took off from our base in Tuscany to head to Emilia (the northwestern part of Emilia-Romagna). This region of Italy is particularly famous for not one, but two delicious types of salumi— Prosciutto di Parma and Mortadella di Bologna! This is why a group of eager students joined us to learn how to make these incredible products for themselves on our Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma. During our induction we dove right into WHY we learn here and discussed artisanal production vs la Grande Industria. We met passionate farmers Giorgio & Claudia Bonacini at their farm, Il Grifo, near Reggio-Emilia. They are the definition of artisanal production. As we toured the farm where they rear Mora Romagnola pigs we heard about how they keep the whole production cycle at home and how they farm their 65 hectares biodynamically. They showed us the Modena cut, how they make salami, mortadella and the method for salting whole pieces. We also had the chance to inject a coscia (leg) with flavoured brine to make prosciutto cotto, but we didn’t have time to cook it. We think it would have tasted absolutely wonderful though! As soon as you ask Giorgio a question, he grabs a pen and sheet of paper and starts illustrating what he's talking about. We sometimes joke that we'll mount an art exhibition of his drawings! One of the parts of the course the students found really interesting was sitting around a table with him and learning how fermentation works. Giorgio loves the science behind curing and fermenting and this passion really rubbed off on our students! We also visited the Brianti family where Aldo and his son Luca rear free-range Nero di Parma pigs and Piemontese cattle on their organic farm. The guys gave us a run-down on a range of salumi typical of Parma—with a break to enjoy Sunday lunch with the family! Here’s a special piece of salumi by the Brianti’s, Fiocco di Santa Lucia. The photo on the front is Luca’s youngest daughter Marika. The fiocco is usually made from one of the leg muscles, but the Brianti’s have started curing one of the shoulder muscles, which they are also calling fiocco. It means ‘ribbon’, so a muscle that is longer than it is wide! Classic prosciutto di Parma was taught by Maurizio Cavalli. He and his family cure and age the Brianti’s prosciutto. In addition to prosciutto, they also produce coppa, culatello, culaccio and fiocchetto. It’s not all about salumi on the course though. We love to give our guests a real taste of the particular parts of Italy we visit. So we also paid a visit to Acetaia del Cristo where we learned all about the production of aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena DOP. Yes, it requires all those words to distinguish the true balsamic vinegar, which takes 12 years to be ready to bottle, from the aceto balsamico IGP, which takes only three months. We tasted it too of course—and discovered for ourselves the huge differences between the two!

Phew! If this has whetted your interest, take a look at our website for more information. And sign up to our newsletter to be the first to know the dates for 2021! |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed