|

As soon as Marzio saw my last blog ‘What Grandparents Ate‘, he phoned to tell me I’d got it all wrong. Picchiante aren’t pig’s lungs; my dictionary is correct: they’re cow’s lungs. Could be. Ismaele rears beef cattle as well, including the rare Pontremolese breed. I emailed Ismaele to find out what he’d given Marzio. The reply just arrived with a variant of the name picchiante: ‘Il picchiatello è di manzo’ (the lungs are beef).

0 Comments

Health warning: Vegetarians and hesitant carnivores may find this blog disturbing. At the end of the last Advanced Salumi Course I was chatting with the norcino (pork butcher) Ismaele Turri and my driver Marzio Paganelli outside Ismaele’s butchery. Marzio asked me whether I’d ever eaten picchiante. I’d never even heard the word, so I wasn’t sure. They’re lungs, he explained, and his grandmother used to make a delicious dish with them. Did I want to try them? I wasn’t sure, but thought I ought to in the name of research. Problem is, where could he get them? He hadn’t seen them at a butcher shop in years. Ismaele rears pigs, and when one is slaughtered, he gets the whole animal back from the abattoir—head to tail, skin, offal, bones and blood. Nothing missing. He led us into the cold room; I briefly saw something long, grey and smooth before he popped it in a plastic bag and handed it to Marzio. No money changed hands. We fixed Tuesday for the dinner. I phone Tuesday midday to check what time to arrive. Marzio is already in the kitchen. He says if it doesn’t come out well, we don’t have to eat it. I consider taking a pork chop. When I arrive at 8 pm, his wife Carla tells me she’d gone out for the day to avoid cramping his style. I’m relieved that there are good smells coming from the kitchen. Marzio loves to recount recipes as if they were stories. This is what gave me the idea of ‘Cooking with Babbo’. Babbo is the Tuscan equivalent of ‘dad’ or ‘pa’. I bring my guests to the Paganelli’s summer haunt, a renovated chapel on the ridge above their home in the valley, and we cook whatever Marzio feels like. No menu, no recipes. While a ragù simmers, he’ll grab a jug and lead you down to the spring below the house, or take you to the veg patch to pick tomatoes. Carla is there too, and steps in to teach her to-die-for tiramisu. As a rule I don’t approve of cooking lessons as the only introduction a traveller gets to our food. Tuscan cuisine relies above all on good primary ingredients, and you have to know where to find them and how much better the flavour is than industrial food. That’s why I take my guests to visit artisan farmers and producers. But ‘Cooking with Babbo’ is as much a lesson in the dynamics between Italian husbands and wives as a cooking lesson. It’s a cultural experience. This time Marzio lifts the lid to a simmering pot and shows me the deep, rich red sauce from which small brown cubes of meat protrude. The story begins. He chopped two onions and sautéed them for several minutes in extra virgin olive oil, pressed from his own olives. He had already prepared the lungs. That’s what took longest, because you have to remove all the tubes so the finished dish won’t be chewy. He added the cubed lungs to the onions along with a small clove of garlic and a pinch of peperoncino (chile pepper), and sautéed them for an ‘abundant 15 minutes’, splashed in some white wine and evaporated it (sfumare), added chopped, peeled tinned tomatoes (much better in winter than tasteless hothouse ones) and some tomato paste. Then some hot water (or vegetable stock) to cover. He put the lid on the pot and simmered it for ‘an abundant 50 minutes’. Time is often as important an ingredient as the physical ingredients. The recital over, the pot is brought to the table along with a platter of hot, fairly firm polenta which he has piled in a mound and decorated with a fork. Formenton otto file, he states. It’s the old variety of maize whose stoneground meal makes polenta that actually tastes like corn. He cuts a slice of polenta with a knife and struggles to carry it to my plate. His grandfather used a pliable willow branch, which was perfect for cutting the polenta and getting the slice to a plate in one fell swoop. Carla spoons the picchiante in umido, the lung stew, to the side of the polenta. We look at each other, exchange the ritual buon appetito, and taste it. I’d expected a slightly slimy texture, but the cubes of lung are resistant while not being tough and the flavour is deep and complex. Truly delicious! As we enjoy Marzio’s creation, we ponder the origin of the word ‘picchiante’. The Italian for ‘lung’ is ‘polmone’. Maybe it’s Tuscan. When I get home, I check my Italian-Italian dictionary compiled by two Tuscan scholars, Devoto and Oli. They confirm the word as 16th-century Tuscan, but say it refers to the lungs of a cow. Nevertheless, the Italians in my village know I’m talking about pig lungs when I tell them what I’ve eaten. It also means door knocker, and was applied to lungs because they lie near the heart. Marzio and Carla talk nostalgically about all the ingredients that have disappeared from shops and the dishes that no one makes anymore. They think young people don’t like them, and wouldn’t eat them even if their parents could be bothered to prepare them. Every year Carla’s family reared a pig which they slaughtered in January. Marzio and I chorus, ‘Il giorno di Sant’Antonio’, the 17th of January. Sant’Antonio is the patron saint of animals, and it always seems strange to me that this is the day of the slaughter, but Carla thinks he only protected young animals. Anyway, no part of the pig was wasted; there were traditional ways of eating or using everything. Not only every cut of an animal was used, but a large variety of wild and cultivated plants formed part of the daily diet. This is partly old people’s talk. We’re at that age when the world seems to be going to the dogs. But I’m cautiously optimistic. I see hopeful green shoots: farmers’ markets, artisan bakers and butchers, restaurants featuring liver, pigs’ feet and foraged plants. And Marzio is still making his grandmother’s picchiante in umido.

Participants on our Advanced Salumi Course taste a vast array of salami, prosciutto, capocollo, soppressata and other cured pork delicacies, some not so delicate. For dinner they get to try other typical dishes of the areas where the course takes place. On our first night we’re in Versilia, the northern coast of Tuscany. Gabriella Lazzarini, one of my cooking teachers and a skilled chef, lives here near Viareggio and invites us to her home for a seafood meal, which is one of the highlights of the course. Not only is it special eating in a private home, but Gabriella’s repertoire of local recipes is exceptional. She buys fish from the small family fishing boats called pescherecci that bring their catches to the molo (quai) in Viareggio. They fish off the rocks close to the coast, and the fish look strange to people who are used to seeing branzino (sea bass), orata (gilt-head bream), tuna and other large, usually farmed or endangered species served in most of the seafood restaurants here. You don’t have to enrol in the salumi course to eat at Gabriella’s home. All Sapori e Saperi Adventure’s guests can choose a meal with her as one of their activities. The other unique dining experience is on Saturday night after we’ve moved east over the Alpi Apuane to Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. We go to the Osteria Il Vecchio Mulino where our host is Andrea Bertucci, who is known affectionately as ‘Andreone’, which means ‘big Andrea’. You can see that the love of his life is food. But Andrea doesn’t cook; in fact, his osteria doesn’t even have a kitchen. Andrea is a food collector. He finds the best products in the Garfagnana, and sometimes further afield, which he serves as a tasting menu. The nearest analogy is a tapas bar, but his place is more like a hybrid of a corner grocery, wine bar and a cheese and salami maturing cellar. Since the menu depends on his latest finds, there are always surprises. In his tiny oven, not a microwave, he heats crostini and savoury tarts. There’s usually a salumi board, but I suspect we’ll be salumied-out on the course and ask him for alternatives. On a two-burner electric hot plate he warms up local specialities prepared by his mother or friends. This time it’s polenta formenton otto-file, an heirloom variety of corn, with roe deer ragù. Every time we thank Andrea and say we must leave, he produces another goodie: cinta senese salami, cured roe deer loin, fruit salad he made that very day, 15 February, which is San Faustino’s Day, the patron saint of singles. I’ve checked on Google and it’s true!

I always get excited about the winter Slow Food Soup Tournament. The 2014 dates of the Disfida della Zuppa have just been announced. The displays of skill of the competing zuppistiare a wonder and will satisfy the mid-winter yearnings of any hungry foodie. Compare it to eating the Ladies’ Moguls Freestyle Skiing. I’ve written about zuppa in several blogs (if you’d like to read more, see below for the links), so this time I’m just going to tell you briefly what zuppa is and translate the email I received this morning soliciting zuppisti to enter the Tournament. Zuppa derives from the 16th-century ‘suppa’ which means ‘a slice of bread impregnated with liquid’, a sort of crouton. The Lucchese zuppa alla frantoiana, the protagonist of the Tournament, supposedly originated at olive presses (frantoio means olive press). After you pressed your olives, you took your new oil to the fireplace in the frantoio where a pot of soup was simmering over the flames. The press’s owner put a crust of bread in a bowl, ladled the zuppa over it and you seasoned it with a drizzle of your oil. Since olives were pressed between November and January, the ingredients were winter vegetables. (Nowadays the fashion is for bitterer, more piquant oil and many olives are pressed in the second half of October before they’re completely ripe.) This year there will be 11 matches before the semi-finals and the ‘Cup Final’. Anyone who makes zuppa can compete, whether mamma, son, aunt or professional chef. The philosophy behind zuppa is deep and produces endless discussions at the matches. What are the essential ingredients? At past tournaments the consensus has been: dried beans, olive oil, bread and cavolo nero. In the realms of ‘freestyle’, you can add wild edible herbs, seasonal vegetables, whatever your family recipe includes or whatever takes your fancy. What’s not allowed? Unseasonal vegetables like zucchini. In the light of this, Slow Food’s call for contestants is poetic and provocative: Non è mai troppo tardi per partecipare alla disfida ed entrare nel’albo ufficiale degli zuppisti lucchesi. Portate la ricetta della nonna, della zia, della trisavola, la vostra. Con erbi, senza erbi, con pane, senza pane, con cipolla fresca, senza cipolla fresca, ne abbiamo vite tante, ma non ancora tutte. La ricetta della zuppa è per definizione una ricetta che non esiste, se non nell’esperienza di chi la fa e ne custodisce i sapori, i profumi, gli aromi, i ricordi. Which means: It’s never too late to participate in the tournament and enter the official annals of Lucca soup makers. Bring the recipe of your grandmother, your aunt, your great-great grandmother, your own. With herbs, without herbs, with bread, without bread, with fresh onion, without fresh onion, we’ve nourished ourselves with many, but not yet all. The recipe for zuppa is by definition a recipe that doesn’t exist except in the experiences of those who make it and preserve the flavours, the fragrance, the aromas and the memories. The jury is us the public, so if you’re near Lucca between now and the end of March and want a truly Slow Italian experience, contact me at [email protected] and I’ll book you in for the date of your choice. But hurry, the competitors are world class and the games sell out quickly. Dates of zuppa matches

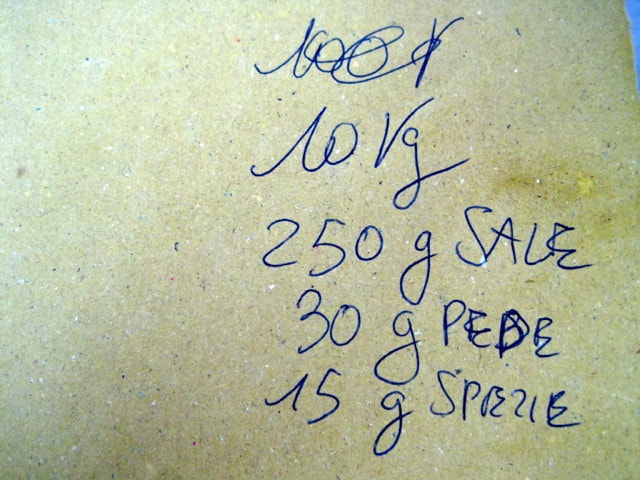

13 February: Ristorante pizzeria “i Diavoletti” di Camigliano, 18 February: Sala parrocchiale di Capannori, 21 February: Rio di Vorno, 26 February: Antica e Premiata tintoria Verciani – il Mecenate a Lucca, 28 February: Osteria da mi pa’, 1 March: Aquilea, 7 March: Osteria storica morianese da Pio, 8 March: Agriturismo Alle Camelie, 14 March: Sala parrocchiale di Carignano per il gruppo Equinozio, 21 March: Rio di Vorno per i Gruppi GAS Lucca Pisa, date to be announced: Pecora Nera Links to my other zuppa blogs: Soup Tournament, Elegy to Soup, Soup Put to the Test, Souprize, Slow Food Disfida della Zuppa or Soup Tournament, Another Zuppa If your lifelong dream has been to stuff a pig in a sack, your moment has arrived. French charcuterie, Italian salumi, Spanish jamón and English cured meats are all the rage. Not only are gourmet hams and salamis hogging (sorry, I couldn’t resist) the cold counters at fashionable delicatessens and stylish online shops, but every farmers’ market boasts a stall or more selling artisan salami made from rare breed pork. Want to learn to butcher a pig, salt a pancetta? Just type ‘charcuterie course’ into Google and you get 2,360,000 results for courses from Dorset to Down Under by way of Denver. If you’re a butcher, chef or pig breeder wanting to make Italian salumi, your choice is more limited. Even though when you enter ‘salumi course’, you get 237,000 results, not many are designed for professionals. But the top four are and they’re us: the Saperi e Saperi Advanced Salumi Course. Everyone who comes tells me our course is unique: it’s aimed at food professionals; it takes place in Tuscany; it lasts for four days, short enough for a small-scale pig breeder to get away and long enough to cover the subject in depth; the price is moderate—you don’t have to sell the farm or the restaurant to come. In my opinion, what makes the greatest difference is that we’re in Italy. ‘We’ is course leader Giancarlo Russo, native Tuscan, and course organiser me, adoptive Tuscan. We know there’s no such thing as ‘Italian’ salumi, nor even ‘Tuscan’ salumi. Move 20 km and you find different styles and practices. We know if we use only one norcino to teach the course, participants will get a totally skewed idea of how salumi is made. They’ll think there are rigid rules, because each norcino is sure his method is best. Giancarlo is consultant to Slow Food on meat and contributor to the book Salumi d’Italia. He knows the vast range of salumi in Italy and that there’s no hope of covering all of it. What to do? We base the course in northwestern Tuscany and use three norcini more than 20 km apart. In his theoretical sessions Giancarlo covers some practices in other parts of Italy. We’ve chosen our norcini carefully. All of them are at least third generation butchers, having learned from grandparents and parents. They are true artisans. They are aiming at excellence, not a uniform product. They use the best maiale pesante (heavy pig of more than 155 kg) they can get, always Italian. They don’t use starters, sugar or milk powder. They use a small quantity of potassium nitrate (E252), never nitrites. They dry their salami either naturally or in a drying cupboard and mature their products in a natural cellar. They reveal all their secrets except the exact mix of spices, which is a family recipe. You’re encouraged to take photos and videos. They want you to go home and make good salumi. Otherwise, they’d be wasting their time. Our first norcino is Massimo Bacci from Versilia, the northern coastal plain of Tuscany. Massimo is a consummate salumi maker and a natural teacher. He’s clear and patient; he explains and demonstrates and allows you to tie a salami as many times as you need to get it right. Massimo explains the stages in drying and maturing, and he produces the best lardo I’ve ever tasted, using the same marble basins as in Colonnata, higher up the mountain from him. His 83-year-old dad pops in from the adjoining shop every 20 minutes to make sure his 60-year-old son is giving us the correct instructions. Their mortadella nostrale (a salami, not cooked like mortadella di Bologna) always comes first or second in the all-Italy artisan salami competition. From Versilia we speed down the autostrada to San Miniato, a town along the Arno River between Florence and Pisa, where we visit Maurizio and Simone Castaldi, two brothers who learned their art from their father and uncle. We first came to them so we could include the fennel-flavoured salami finocchiona in the course. The finocchiona zone lies between Florence and Arezzo, south of our other two norcini. During our first visit, we discovered that their strongest suit is the production of prosciutto, and we now include an in-depth study of prosciutto from salting to air drying. Now we head to our third norcino at Venturo farm in the Garfagnana, the mountainous area north of Lucca. We’re just over the Apennines from Parma and Modena in the Po Plain, so many of the products are the same. Ismaele Turri learned from his father, as well as working in a neighbour’s butcher shop from the age of 14. He’s a farmer and pig breeder. He slaughters two of his largest pigs in honour of our course. Participants are guided from the butchering of the pig to all the various typical salumi of the Garfagnana: prosciutto toscano, coppa, guanciale, pancetta, salami, cotechino, soppressata, biroldo (blood sausage) and a few other surprises. Since we allow no more than seven people on the course, there’s lots of time for hands-on practice. If you stay for the extension workshop on the Tuesday after the course, you watch a production run at the Rocchi family salumifico near Lucca. Their efficiency is a sight to behold. At the end of the course we ask for feedback, which Giancarlo and I use to improve the course to meet the needs of future food professionals. Even experienced butchers who already make salami tell us they learn a lot on the course. Last year a couple who came on our first course got their salami accepted by Harrods. We’re proud to be the launchpad for such successes.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed