|

Passing through Saltocchio on the train from Pisa Airport to Bagni di Lucca reminds me of the obscure piece of information revealed to me by the carpenter repairing the windows of my hosue. ‘Saltare’ means ‘to jump’ and ‘occhio’ means ‘eye. The name of the parish supposedly derives from the accident that befell one of Hannibal’s elephants, which lost an eye in a battle at that very place along the Serchio river.

0 Comments

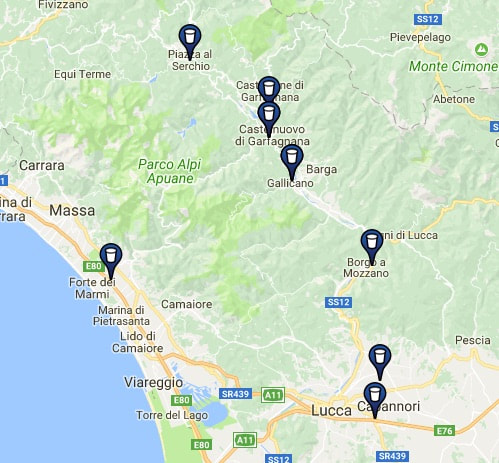

On the way back from a cooking lesson I’d arranged for clients, I’m crawling along at a Slow Food snail’s pace (no doubt infuriating the rush-hour drivers behind me) when I spy the little wooden hut I’m searching for. The hut — a kind of mini-barn — shelters a machine that dispenses unpasteurised milk almost straight from the cow and is part of an Italian rural development programme to shorten the supply chain and put consumers’ money directly into the pockets of farmers. The farmer tests every batch of milk with the lab equipment in his barn. Health and safety officials also check the milk regularly. There’s a website where you can find all the ‘mechanical cows’ in Italy. Here are the ones near me. A crowd of customers is gathered round, each hugging one or more empty glass bottles. It looks like happy hour at a bar, but as I get closer, I realise they’re waiting for the young farmer to clean and refill the ‘mechanical cow’. The landscape being more industrial than pastoral in this part of the Capannori, I ask the farmer how far away his farm is. He pulls me a few steps to one side and points through a gap in the buildings to his cow barn, about half a kilometre from us. Not many food miles required to fill the machine. Sensing a captive audience, he signals me over to his milk truck and opens the side door to reveal a secret cargo… Lying on the back seat is a large bunch of stringa. His own produce he proudly explains, harvested that afternoon for a customer who will be arriving any moment, so he regrets he can’t sell me any. ‘Stringa’ means ‘shoelace’ and refers to a small diameter green bean, grown only in the Lucca plain and nearby Versilia, that reaches 70–80 cm in length — more a bootlace, really. I explain that I organise gastronomic tours to visit small producers and ask whether I could bring some guests by to see his farm. He suggests I telephone next time I’m passing and he’ll show me around. He returns to his work, now filling the bottle dispenser with new glass bottles, for new customers or those who have forgotten theirs at home. By now the crowd has dispersed and I fill my own bottle. The milk costs 1 euro a litre and, for small consumers, you can buy it in units of 100ml, rather than having to buy a whole litre at once. It tastes intensely of milk, unlike the white liquid one buys at the supermarket, which costs €1,40. I say arrivederci, but he’s loath to lose a sympathetic ear. He looks indecisive, then makes up his mind, goes to the truck and steals a large handful of stringa from the bunch on the seat. ‘Here’, he says, ‘You know how to cook them, don’t you?’ ‘Yes, stew them with onions, garlic and tomato.’ ‘They’re delicious with rabbit, but only with my grandmother’s.’ He reminisces, ‘When I was a boy, I refused to eat rabbit if my mother bought it from the butcher. It didn’t have any flavour compared to my nonna’s. But she’s gone now, and I don’t have time to keep chickens and rabbits’, he continues wistfully. I promise to return soon, and bear my booty home to stew my stringa.

Last Thursday Cristina, who owns the restaurant the Antico Uliveto in Pozzi di Seravezza, and I walked up to the high pastures of the Alpi Apuane in northern Tuscany to visit a couple who are among the very few who still take their flock of sheep up to the mountain tops in summer. They live in a house powered only by a single solar panel and cook over an open fire in the large kitchen fireplace. Our lunch was composed almost entirely of their own produce. It included a porcupine that had been eating their squashes and melons and which Siria, the wife, had made into a delicious stew with their own tomatoes and a few olives brought up from the valley. When we arrived she was just beginning to fry some of the potatoes they grow, and soon had a huge pot of water hanging from a hook over the fire. As soon as it boiled, she added handfuls of maize flour (she apologised for it’s being last year’s — they’ve harvested this year’s maize but haven’t been down to have it ground) and we took turns stirring until it thickened into a soft polenta. It didn’t matter at all about it’s being a year old; it was Maranino maize and tasted like the corn it came from, unlike the tasteless polenta flour you can buy in a supermarket, or even most Italian delicatessens. We washed it all down with a very drinkable red wine made by the husband Pacifico. The meal ended with Siria’s pecorino cheese and sweet juicy plums from their orchard. After a cup of coffee and walnut liqueur (nocino), also made by them, Pacifico took us to see La Fannia, a beech tree at the top of the ridge that is said to be over 500 years old, and an abandoned silver mine, now the refuge of some rare red-bellied salamanders. We walked down as the sun set over the sea at Forte dei Marmi lighting up Monte Forato behind us. A day with Siria and Pacifico will definitely be on offer to gastronomic tour guests next summer.

September 2017: Since I wrote this blog, Siria and Pacifico decided they didn’t want visitors disturbing their peace. I don’t blame them, but it’s a loss to us. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed