|

‘The golden rules of authentic paella’ caught my eye on the ‘Food & Drink’ page of The Week(19 July). It reported that a ‘paella activist’ had founded a group dedicated to the preservation of Valencia’s signature dish. I signed into their website en.wikipaella.org to explore more. In answer to the question, ‘Is there a unique authentic paella recipe?’ I read the reply, ‘Each zone and season offers variations and peculiarities, and there are as many versions as villages and cooks’. So why are they worried about variations in the recipe? In what does ‘authenticity’ exist? Part of the answer must lie in the next sentence: ‘All of them use ingredients taken from the land. This is what nowadays is called Gastronomy KM0.’ The land is the territory of Valencia, and what can’t be found there can’t be used in paella. Maybe one should say, ‘what couldn’t be found there in the past’, but this raises another question of how far in the past does one draw the line? It reminded me of the Slow Food Lucca Compitese’s successful efforts to keep alive the traditional zuppa alla frantoiana through their annual zuppa tournament. Many variations exist, but to stay true to its origin during the olive harvest at Lucca it must contain beans, cavolo nero, stale bread and extra virgin olive oil. It may contain other winter vegetables, but absolutely no zucchini even if they are now grown in hothouses and imported to the area. The same applies to tomatoes. Risotto could use an action group too. It originated as a sort of rice porridge. The finished dish should be all’onda, as important a concept in cooking a risotto as al dente is to the correct cooking of pasta. The final consistency of risotto should be not too liquid and not too dry; when you shake the pan (a shallow, wide pan please) the risotto should form a wave (onda). How many risottos have you had that are more like paella? The website tells me, ‘As we all know, rice in authentic Paellas must stay dry and loose.’ This conservationist attitude to traditional dishes seems to be rare in England and the United States (and for all I know, in other countries too). Their citizens happily appropriate the names of dishes, but not the constraints. Any old dish made with rice might be variously titled ‘paella’, ‘risotto’ or ‘pilau’ with scant regard for their origins. I’ve had ‘cassoulet’ in England that was English pork sausage and tinned beans in tomato sauce. Some of these variations in foreign lands may be delicious, but why not give them different names? Risotto isn’t traditional around me in Lucca Province. Here a dish based on rice is usually called ‘riso ai funghi’ (rice and wild mushrooms), for example, on a restaurant menu. This neither capitalises dishonestly on a famous dish, nor distorts the public’s idea of what the true dish should be like.

So in addition to preserving traditional cuisine, let’s celebrate new untraditional recipes with creative new names.

0 Comments

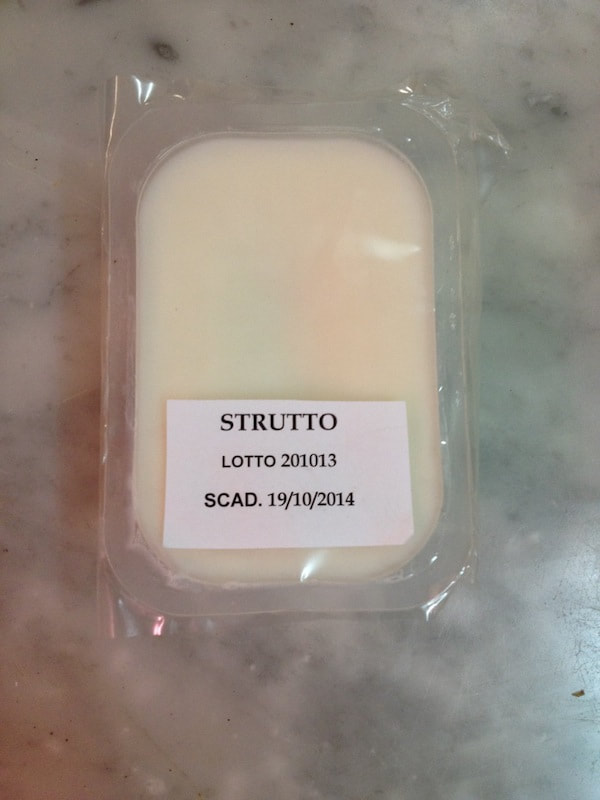

Participants on the Advanced Salumi Course work with three norcini (specialist pork butchers) in three different parts of Tuscany. Recipes and methods change every 20 km, depending on regional variations and family traditions. If people stay for the extension workshop, they experience a fourth point of view with another family. They learn to make authentic Tuscan salami, prosciutto, and several other air-dried and cooked pork products. One of the lesser known of these are ciccioli, or grassetti as they’re called in the Garfagnana. Grassetti are the crispy residue of producing lard, much used in the past for frying and baking, especially in mountainous areas at altitudes where olive trees are less well adapted than the pig. The process entails cutting pork back fat (without the skin) into cubes… …and rendering it over a low heat until the pieces are brown. Then the pieces of hot fat are put in a press to squeeze out as much liquid fat as possible. The resulting pork chips are salted and drained on absorbent paper. They’re more addictive than salted peanuts, and chefs who attend the course realise immediately their potential as bar snacks. Gina Piazza (whose husband Kirby Piazza took most of the photos in last week’s blog ‘Like the Seasons: the Life of a Cheesemaker’) came on the course in March and sent me this report in early June: We had a press made by a welder friend and from 2 pounds of back fat we came up with a handful of ciccioli—but they’re amazing and I did it just as Ismaele makes it. I have 12 pounds of fat on order so maybe next batch will yield at least a few pounds. Now I have tons of rendered fat! The Advanced Salumi Courses for winter 2014–15 are almost full with one place left on the November course and three places on the February course. For more details of the course see Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany

The cheese course group arrived 45 minutes late at Daniela’s dairy. She had already added the rennet, the enzyme that speeds up coagulation of the curd, to have the curd ready for our planned arrival time. Now it was past its best. We feared we’d ruined her day’s production of cheese. Daniela’s youthful appearance belies years of experience making cheese. She knew the curd couldn’t be used to make a hard cheese to be matured for several months, so we used it to make some soft cheeses: stracchino and raviggiolo. I first went to visit Daniela Pagliai at her organic farm I Taufi early last June. I had learned about it from the address on the wrapping of some exceptional butter I’d come across at a gastronomia in Ponte a Moriano near Lucca. The wrapping claimed the contents were ricotta, so I assumed Daniela also made cheese, and I warmed to a person who wasn’t uptight about precision labelling. (Not that ricotta is cheese, but you have to make cheese first and then use the whey to make ricotta.) The address of the farm was Melo. I didn’t know Melo, but I’d been to the picture postcard town of Cutigliano from which you ascend the Pistoiese slopes of the Apennines, it seems like forever, to get to Melo. What appears on the map to be at the edge of civilisation, turned out to be a hub of pastoral activities with Daniela at the centre. On this first meeting she appeared self-possessed, only mildly curious about my tours and calmly accepting of my request to bring clients to watch her make cheese, as if life often brought novelties to her door. A warm honesty flowed from her candid smile and guileless eyes. She showed me her modern dairy, the maturing room and the cows in the barn. Her younger daughter clung to her apron; the older one arrived home from school. I was much more curious about her than she about me. In the dairy she had fondled a spino, the wooden stick traditionally used to cut curds, so I knew she respected tradition. I asked diffidently whether the cows ever went outside, and was relieved to hear they still practise transhumance, taking the cows to alpine pastures a couple of hours’ walk above where we were now. The cows have to wait until school is out and the whole family can up stakes and move to their summer home. We went to see it without them. On a shelf I noticed a slim book entitled Come le Stagioni: Daniela Pagliai (Like the Seasons), a biography of her written by a friend from Pistoia in the form of an interview. I bought a copy and learned she was practically born making cheese. During school holidays she and her dog herded her father’s sheep. By the time she was 14 she was in charge of the pigs and all the phases of cheesemaking on the family farm. At 16 she married Valter and discovered that his contribution to the marital economy was a herd of milk cows. She moved to her in-law’s farm and transferred her cheesemaking skills to cow’s milk. After five years she and Valter realised their dream of buying their own farm and becoming organic. In the book she sums up her philosophy of life: ‘I think there are many types of “love” all led by the heart. Without its beating, there can be no beginning. I’m not talking only of the beating that pumps blood through our veins, but also the beating for our children, our parents, our house, our land, our work, which are all united in one thing: love. ‘How can I explain to you how much I love my life and my work? How can I make you understand what I feel for my children and my husband? For nothing else in the world and no other life in the world would I change my own life and these loves. ‘For me life is like the seasons: moments of joy are like the flowers and perfumes of spring and like the ripening of its fruit and the embrace of the hot summer sun. Moments of melancholy are like the autumn with its rain, which sometimes also streams from my eyes, and like the winter, because you have to move with the rhythm of the snow, delicately placing your feet like the large snowflakes descending joyously from the sky, sprinkling the roof and our valley, and walking, walking lightly, toward a new spring.’ There was still snow on the ground when I took Giancarlo Russo to visit Daniela in preparation for our new cheese course. He approved, and Daniela became part of the course in which Giancarlo teaches the theoretical sessions. For more information about the Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese course: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/

My thanks to Kirby Piazza for his photographs of Daniela and the farm. Where you lay your head at night can make or break your holiday. Your accommodation seems a simple thing to choose. You go to Tripadvisor, read the reviews and make your booking. You’re looking for a bedroom with a comfortable bed, a bathroom, a decent continental breakfast, cleanliness and friendly attentive staff. That’s probably exactly what you’ll get; a secure place to retreat to after visiting the famous works of art and architecture in some of most beautiful cities in the world. But at the heart of every country are its citizens, people who live differently from you. By your second or third trip, you can begin to think about getting to know them. This is what my tours are about. I want my guests to experience how Italians live their everyday life, which is something you still can’t do on the internet. It’s a compulsive reason to travel to Italy. I seek total cultural immersion, and so I usually choose an agriturismo for my guests, farm accommodation in the countryside, often on the edge of a village. Each one has a character completely its own determined by the personality of the owners, the setting, the architecture of the farm buildings and the produce of the farm. Here are some examples from my part of Italy, the area around Lucca and the spectacularly beautiful Garfagnana. I didn’t choose Al Benefizio; it chose me. Early in my sojourn in Italy I was at an agricultural meeting near Barga, feeling totally out of my element, when two women approached me and introduced themselves in English. One was Francesca Buonagurelli, the owner and farmer at Al Benefizio, and she is one of the main reasons for staying at Al Benefizio.

To read more about my favourite agriturismi around Lucca and the Garfagnana, please go to the full blog at Slow Travel Tours. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed