|

Very few people I know have been to Sardinia. If they have, they went with the kids and stayed on the beach. If I ask people where in Italy they would like to go, Sardinia is rarely in their top 10. Yet it has so much to offer: Even I only went to Sardinia by accident. Some weavers who were coming on one of my Tastes & Textiles tours in Tuscany asked me to take them to visit a woman who weaves ‘sea silk’, the filaments of the beard of a sea mollusc. Reluctantly I agreed and hopped over from Pisa, only 50 minutes by plane to Cagliari, the capital of Sardinia. It wasn’t love at first sight. But, like people, I believe places merit more than a casual glance. Many reveal their treasures only to those who patiently dig below the surface. There’s no better way to get to know a place than to learn from the locals. Enter Antonio Arca. He was born in Alghero in northwestern Sardinia and moved to London in 2004, the same year I came to Lucca. His company Capo Caccia Fine Food imports the products he knows and loves from small, trustworthy suppliers. During one of my research trips to Sardinia, Antonio advised me to go to Sa Sartiglia festival in Oristano, in the west central part of the island. You can read about it here. I was travelling with friends who wanted to go to Cabras to see the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, but I was too engrossed in the festival. I was meeting farmers and family food producers at street stalls. One of these was Marcello Stara, a local rice farmer. I don’t know why I’m so excited by rice. Maybe it’s the flavour of good rice (not the bland quick-cook stuff) and its versatility in different cuisines from Asia to Italy. Maybe it’s the fact that it grows in water and required communal cooperation to provide the irrigation. Maybe it’s just how beautiful it looks in the field. In any case, I was already conjuring a tour to include Marcello and his rice during the harvest so we could find out how it’s processed and what freshly harvested rice tastes like. But one farmer doesn’t make a tour. I consulted Antonio. Did he know know other people in the area? Would he like to collaborate on a tour? Yes and yes. We planned a research trip together. First we needed a place to stay. For me it had to be an agriturismo (farm accommodation) so we would be investing in the rural economy. I found three suitable ones on the internet. Antonio chose L’Orto. Not only do they have enough private rooms with en suite baths, but they have a restaurant and dad is a fantastic cook. Everything local and perfectly cooked. We visited Marcello and his rice fields. He introduced us to Davide Orro and his family in the next village. Davide could almost be a tour in himself. He’s an enthusiastic winemaker and olive farmer and his sister Ester makes decorated festival bread. He planned our day: start picking olives, cure and bottle the olives, learn to make decorate bread with Ester. Lunch: bread, local cheeses and salumi, olives, wine. One of the grape varieties is known to have been grown in the area 3000 years ago. Davide suggested we go see Sandro Dessé. He’s even more versatile than the Orro family. You arrive at his farm and see a paddock of sheep and goats, one of donkeys and horses, pigs at the back and dinosaurs over to the side. Behind the pigs are fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Sandro is a practitioner of the circular economy. Not only does he produce the raw ingredients, but he processes them as well. There’s a small abattoir, a laboratory for curing pork, a cheese dairy and a kitchen for drying fruit and making pasta. His dining room seats 250 guests. Sandro’s wild, wide-eyed enthusiasm is contagious, but we can’t do everything in one visit. We must have a tour of the farm, and it would be fun to have a lesson making the delicious stuffed pasta called culurgiones, which we can eat for lunch along with Sandro’s many other products. Here we pick up the trail of some of Antonio’s friends. Paolo Lilliu, a butcher, who makes the salsiccia sarda, which you can cook when they’re fresh or air dry and eat like salami. On your morning with Paolo you’ll make your own, after which we’ll go to his friend Sandro Picchedda, a saffron and peperoncino (chili pepper) farmer for a barbecue and a traditional dessert made with saffron. Some other friends of Antonio introduced us to cowherd and cheesemaker Giuseppe Sanna who makes the Slow Food Presidium cheese casizolu from the milk of his own cows. He's willing to let you try your hand at forming the cheeses. My friends came back wide-eyed and enthusiastic about the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, bigger than life-size stone statues of warriors which probably date to around 800 BC. Having been an archaeologist, I had to see them too. Luckily they reside in the seaside town of Cabras, which is also a centre of bottarga production. We talked to several producers who told us about the technique for fishing the grey mullet, cleaning them and salting and curing the roe to make the much sought after and expensive delicacy bottarga. The gentle and generous Giovanni Spanu invited us into his production facility. The Giganti were even more impressive than I had imagined. They immediately became the mascots of the tour—little-known giants, the heroes of their land. Our living giants are smaller and gentler, but fighting all the same to maintain their products of quality and the role of the small farmer and producer in an ever more global economy.

Find out more about the Giants of Sardinia tour here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 26 August, 2018.

1 Comment

The etymology of the Italian word antipasto is ‘anti’ meaning before and ‘pasto’ meaning meal. My Italian-Italian dictionary adds that they are served before the beginning of the true and proper meal. So, how much can you eat right before you eat a ‘true and proper’ Italian meal? Remember that it consists of two courses, the primo or first course and the secondo or second course. The second course may have side dishes, contorni, and is often followed by the dolce, or sweet course. The Italians I know have differing opinions about the correct number of antipasti (plural of antipasto) to be served at a ‘true and proper’ meal. Stefano of Cantina Bravi in the Garfagnana can’t bear to serve fewer than seven. Nor can Agriturismo L’Orto in Sardinia (if you count the olives). Despite my begging her to reduce the number, Gabriella ignores me and continues to produce five at the seafood dinners she prepares for my salumi courses in Tuscany. Which would you choose? Returning to the dictionary, it says the antipasti are supposed to whet the appetite. Personally, I find more than one puts a damper on my appetite for the rest of the meal, and finally I’ve found some Italians who agree with me. I invited Marzia (one of my cheesemakers) and her husband to dinner last night. Since I figured one antipasto would never satisfy an Italian, I decided to serve three. A bit meagre, I knew. By the time we got to the secondo, a stuffed roast guinea fowl, they said they were already full. They declared that antipasti kill their appetites, and they could easily do without any. I must remind them next time my cheese course is at their house for dinner and they serve seven antipasti!

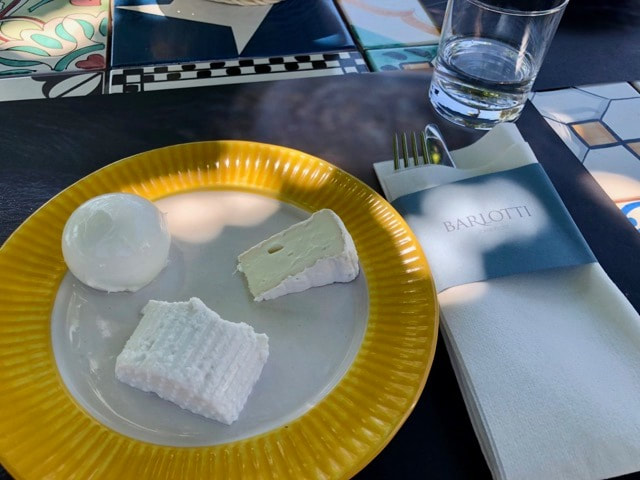

Back to my question: how many can you eat? If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 31 March, 2019. This blog post is part 2 of my recent travels around Italy. You can read the first part 'Food & Wine in Napoli & Pompei' here. But for now, let's start with the second half of my tour... I take the train from Pompei to Salerno and change for the regional train heading south. Maria Sarnataro picks me up at the station at Vallo di Lucania. We arrive at her home just in time for dinner. She has a surprise for me, a manteca. It’s butter encased in caciocavallo cheese and it has a story. The people of Basilicata who take their Podolica breed of cattle to alpine pastures for the summer make caciocavallo which they mature until they descend to the valleys in autumn where they sell it. They make ricotta from the whey, but there’s too much for them to consume fresh. It can’t be kept for more than a few days and there's nowhere to sell it. So, by an ingenious and complex process of draining, heating and cooling, they extract the butterfat from the ricotta. To conserve the butter without refrigeration they encase it in a thin layer of caciocavallo curd. Piero, Maria’s husband, is an agronomist. Part payment for his consultancy with these people was this manteca. There are so many mozzarella dairies in Salerno Province that you could spend several weeks visiting all of them. There are two that I’ve heard excellent reports of and haven’t managed to visit: Barlotti and Vannulo. Vannulo is organic, only sells from their own shop at the dairy and often comes at the top on lists of the 10 best mozzarellas. Maria has booked lunch there. On the way we stop at Barlotti where she introduces me to brothers Enzo and Gaetano Barlotti. We eagerly accept Enzo’s invitation to bring the participants on our mozzarella courses for a tasting. You taste so much bad mozzarella everywhere else that we need to educate our palates while here. He presents us with samples of his bocconcini, ricotta and a new brie-style cheese, all made with the milk of their own buffalo herd. The mozzarella and ricotta are among the best I’ve tasted. The ‘brie’ is a little bitter and needs some work, but it’s exciting that they’re experimenting with new cheeses. Many of the mozzarella dairies offer tastings in beautiful settings and some have a dining room where you can sit down to a multi-course lunch. Vannulo has perfected the tourist experience, which as you probably know by now, puts me right off. Maria is a friend of the owners, but they don’t welcome us when we arrive, and are nowhere to be seen. Maria tells me that it used to be different, but now it’s all hired staff, who display not an ounce (not even a gram) of passion for their products. Our vegetable salad from their organic garden is good, the mozzarella not outstanding. They’ve installed a leather workshop which sells their own handbags, etc, but they take no interest in us visitors. The museum of agricultural implements is marginally interesting, but I’ve been to better ones. If you come on the mozzarella course, you won’t be visiting Vannulo on our tasting afternoon. Francesca Fiasco’s vineyard at Felitto couldn’t be further from a tourist experience. The only sign on the road is Francesca herself waiting to show Maria and me her vineyards and cantina (cellar). She exudes passion and authenticity and does virtually all the work herself right down to designing the labels. She cultivates autochthonous varieties such as fiano, aglianico and piedirosso (the one I saw at Pompei) as well as varieties such as sangiovese and merlot, which arrived in the area so long ago that they are included in the DOC. She produced her first wine in 2016 and is already being recognised by wine critics. She gave me a case of wine with a handwritten label. Sadly, I couldn’t carry it back to Lucca on the train. I know Maria will make good use of it. She not only teaches cheese courses, but also sommelier courses. Just so you know my trip isn’t all hard work eating and drinking, this morning Maria takes me to her favourite secluded beach, fairly free of tourists (especially in these times of Covid-19). You have to go a long way to find gelato as good as Mirko Tognetti's of the Cremeria Opera at Lucca. Here I am at Sapri in southern Campania enjoying Enzo Crivella’s latest creation which he’s describing animatedly. They sound an unlikely combination, but it works. Try it! You have to make a perfectly balanced bread gelato. Maybe best to come on Mirko’s and my gelato course first! 😃

That marks the end of my tour. I'd love to welcome you onto one of our tours or courses soon. Take a look at our website to find out dates and details and get in touch with me to book your spot. I look forward to seeing you! Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

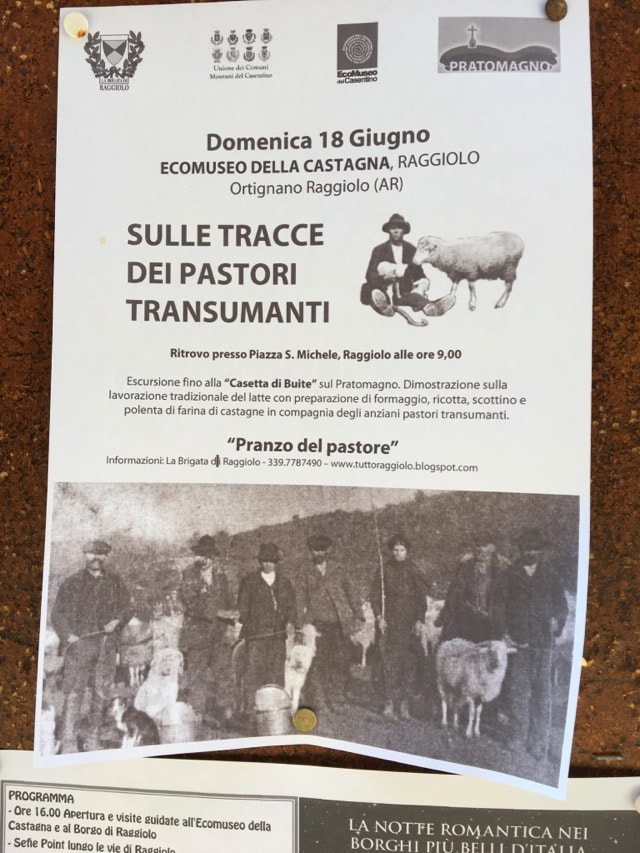

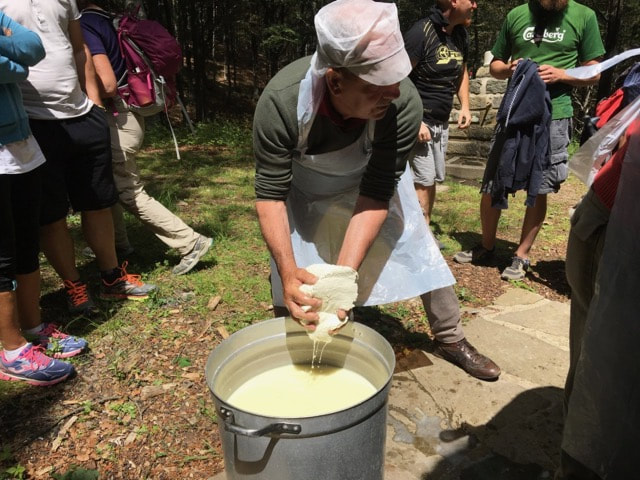

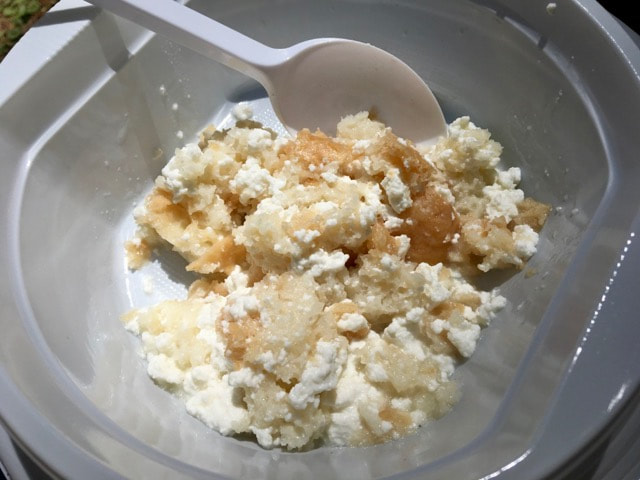

This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

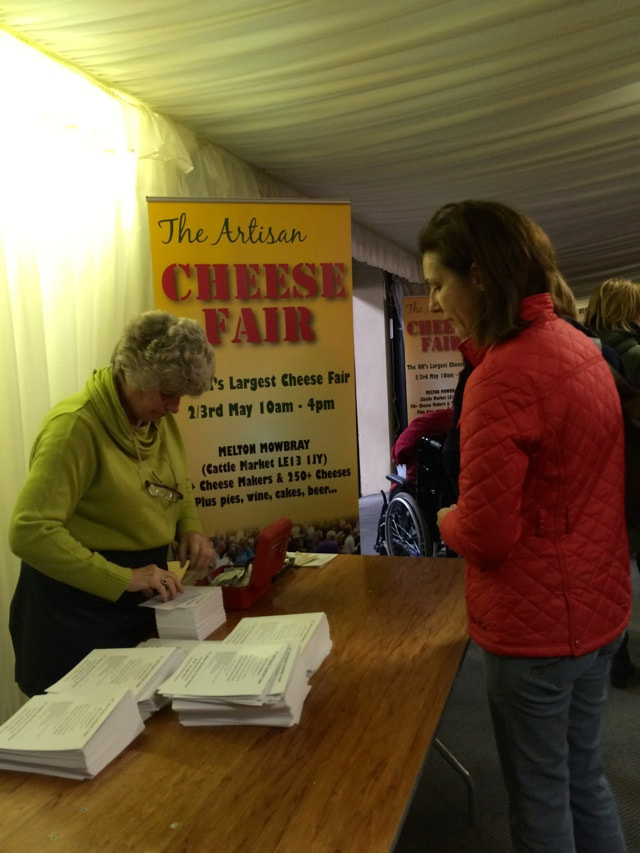

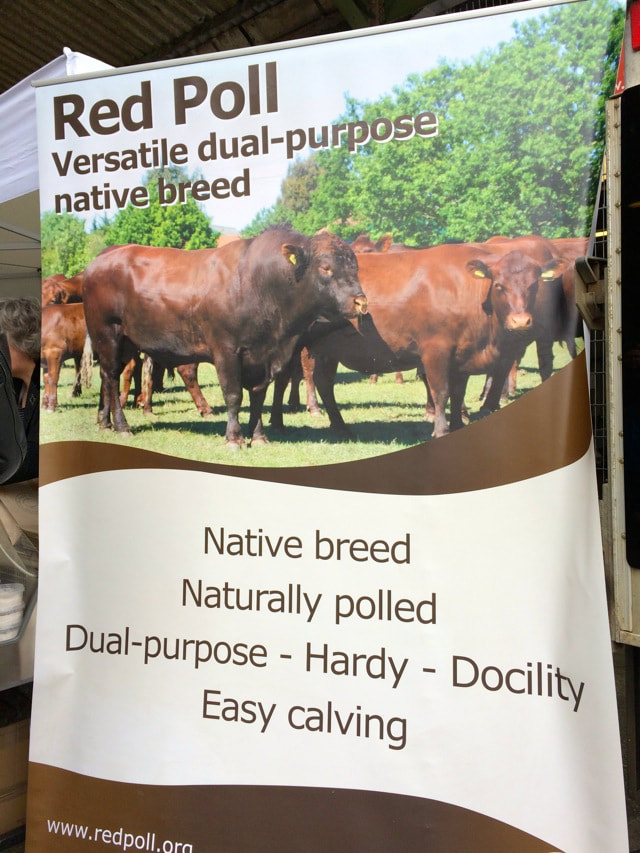

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html At the end of my Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I organise a little game: an England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament. This entails a trip back to the UK immediately before the course to go to Neal’s Yard Dairywhere I can always find a few excellent sheep cheeses. For the May course I did my shopping instead at the annual Artisan Cheese Fair at the old Cattle Market in Melton Mowbray. Although in its fifth year, I had never heard of it, but being featured by the Specialist Cheesemakers Association, I figured it would be worth the trip to Leicestershire, a direct train journey from Cambridge on the line to Birmingham, from where my friend Amanda joined me. It’s also one of the counties, along with Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, in which Stilton is allowed to be made. (Stilton, like Parmigiano Reggiano, is a registered product with a Protected Designation of Origin.) Unlike the market in Cambridge, which is today a ‘cattle market’ in name only, the one at Melton Mowbray still functions every Tuesday morning. I make a resolution to come back to witness the livestock auction. Turning to the entrance to the cheese fair opposite, we find the entrance fee is only £2 and admits you not only to the area populated with vendors’ stalls, but also to a series of cheese classes and tastings. The Red Poll Cattle Society was founded with the aim of preserving this versatile native breed. They note the long lactation period and ideal composition of the milk for cheesemaking. The British Isles are a land of cattle. Sheep these days are reared for meat, and it’s harder than I expected to find sheep’s milk cheese. These people from Canterbury can’t offer any. Amanda has served me excellent goat’s milk cheeses made by Pete Humphries of White Lake Cheeses in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, heart of cheddar country. At the far end of his stall, I glimpse a label saying ‘No Name Sheep Cheese’. He’s begun experimenting with sheep’s milk and this cheese is so new that he hasn’t come up with a name yet. It’s a bit young to compete with the mature pecorinos in the Italian team, but I hope it will make up in youthful energy for what it lacks in experience. Sharing a corner stall are two outstanding talents of British cheese, Jamie Montgomery who makes arguably the best cheddar in Britain, and Joe Schneider who makes Stichelton. Amanda and I found the farm on the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire for Joe and Randolph Hodgson of Neal’s Yard Dairy when they were setting up the dairy to produce what they expected to call ‘raw milk Stilton’, a return to how Stilton was made for centuries. However, due to an anomaly in the PDO definition of Stilton, it can only be made with pasteurised milk. One of the Dairy’s customers suggested Stichelton, an early name for the village of Stilton. Joe welcomed us to the stall and gave us a good chunk of this incomparable cheese to take home. Notice in the photo that the Stichelton isn’t excessively blue. The flavour of the blue mould doesn’t kill the flavour of the cheese. In search of two more sheep cheeses we crossed to another pavilion, passing a ukulele band and an artful display of Quickes Traditional Cheddar. Right at the entrance was the stall I needed. Carlow Farmhouse Cheese had brought several mature sheep’s milk cheeses to the fair. They don’t have their own website, and this one only admits to cow’s milk cheese. Their cheesemaker, Nadja, guided us through her samples. It was hard to choose, but I finally took some ‘pecorino-style’ and ‘cheddar-style’. Business done, we threaded our way through the crowds to a promising-looking pork pie stall. The pies were obviously raised by hand. The pastry is made by mixing hot melted lard with flour. It has to be exactly the right temperature to form it around the wooden moulds (see photo above)—not so hot that it burns your hands and not so cold that it cracks. The baker himself sells us our pie. He reminds me of my Italian artisan food producers when he talks about the natural ingredients he uses: the flour from a nearby windmill, pigs from a local farm and pig’s-foot jelly he makes himself. He’s sold 300 pies this morning and will be off soon to make another 300 for the next day’s fair. With a glass of incredibly strong cider, we settle down to lunch. I used to make pork pies myself, but these pies beat even my best. The crust was crunchy, the filling tasted like pork (not overpowered by spices and preservatives) and the jelly was well seasoned and firm without being rubbery. Melton Mowbray is a pretty market town, but even without its other attractions, it would be worth a pilgrimage for the King’s Road Bakery pork pies alone.

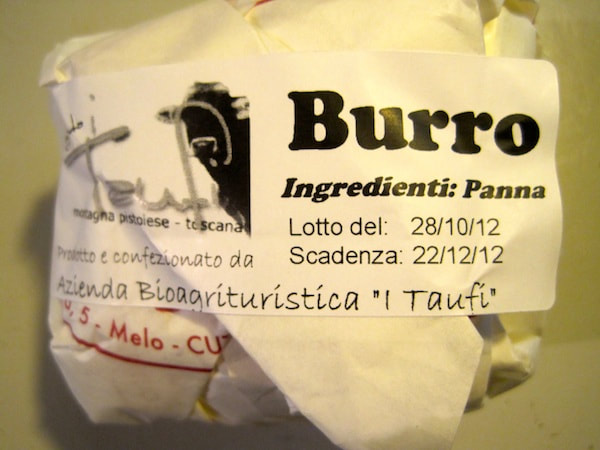

Italy is usually the clear winner of the pecorino match, but this time Ireland came out top in the opinion of our maestro Giancarlo Russo, a judge in international cheese competitions. Young ‘No Name’ was a big hit too with several of the course participants. The cheese course group arrived 45 minutes late at Daniela’s dairy. She had already added the rennet, the enzyme that speeds up coagulation of the curd, to have the curd ready for our planned arrival time. Now it was past its best. We feared we’d ruined her day’s production of cheese. Daniela’s youthful appearance belies years of experience making cheese. She knew the curd couldn’t be used to make a hard cheese to be matured for several months, so we used it to make some soft cheeses: stracchino and raviggiolo. I first went to visit Daniela Pagliai at her organic farm I Taufi early last June. I had learned about it from the address on the wrapping of some exceptional butter I’d come across at a gastronomia in Ponte a Moriano near Lucca. The wrapping claimed the contents were ricotta, so I assumed Daniela also made cheese, and I warmed to a person who wasn’t uptight about precision labelling. (Not that ricotta is cheese, but you have to make cheese first and then use the whey to make ricotta.) The address of the farm was Melo. I didn’t know Melo, but I’d been to the picture postcard town of Cutigliano from which you ascend the Pistoiese slopes of the Apennines, it seems like forever, to get to Melo. What appears on the map to be at the edge of civilisation, turned out to be a hub of pastoral activities with Daniela at the centre. On this first meeting she appeared self-possessed, only mildly curious about my tours and calmly accepting of my request to bring clients to watch her make cheese, as if life often brought novelties to her door. A warm honesty flowed from her candid smile and guileless eyes. She showed me her modern dairy, the maturing room and the cows in the barn. Her younger daughter clung to her apron; the older one arrived home from school. I was much more curious about her than she about me. In the dairy she had fondled a spino, the wooden stick traditionally used to cut curds, so I knew she respected tradition. I asked diffidently whether the cows ever went outside, and was relieved to hear they still practise transhumance, taking the cows to alpine pastures a couple of hours’ walk above where we were now. The cows have to wait until school is out and the whole family can up stakes and move to their summer home. We went to see it without them. On a shelf I noticed a slim book entitled Come le Stagioni: Daniela Pagliai (Like the Seasons), a biography of her written by a friend from Pistoia in the form of an interview. I bought a copy and learned she was practically born making cheese. During school holidays she and her dog herded her father’s sheep. By the time she was 14 she was in charge of the pigs and all the phases of cheesemaking on the family farm. At 16 she married Valter and discovered that his contribution to the marital economy was a herd of milk cows. She moved to her in-law’s farm and transferred her cheesemaking skills to cow’s milk. After five years she and Valter realised their dream of buying their own farm and becoming organic. In the book she sums up her philosophy of life: ‘I think there are many types of “love” all led by the heart. Without its beating, there can be no beginning. I’m not talking only of the beating that pumps blood through our veins, but also the beating for our children, our parents, our house, our land, our work, which are all united in one thing: love. ‘How can I explain to you how much I love my life and my work? How can I make you understand what I feel for my children and my husband? For nothing else in the world and no other life in the world would I change my own life and these loves. ‘For me life is like the seasons: moments of joy are like the flowers and perfumes of spring and like the ripening of its fruit and the embrace of the hot summer sun. Moments of melancholy are like the autumn with its rain, which sometimes also streams from my eyes, and like the winter, because you have to move with the rhythm of the snow, delicately placing your feet like the large snowflakes descending joyously from the sky, sprinkling the roof and our valley, and walking, walking lightly, toward a new spring.’ There was still snow on the ground when I took Giancarlo Russo to visit Daniela in preparation for our new cheese course. He approved, and Daniela became part of the course in which Giancarlo teaches the theoretical sessions. For more information about the Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese course: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/

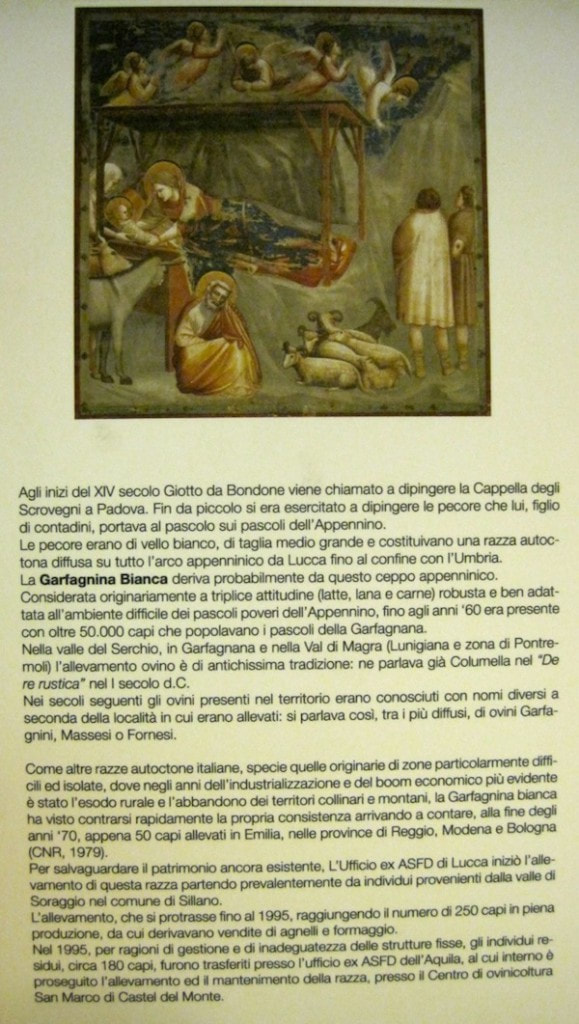

My thanks to Kirby Piazza for his photographs of Daniela and the farm. At noon on Wednesday 9 April in Florence, Dr Francesca Camilli of the Italian National Research Council will present a paper to the 1st European UNESCO-SCBD* Conference on ‘Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe’. Her paper is entitled: ‘The Garfagnana Model: exploitation of agricultural and cultural biodiversity for sustainable local development’. One of her prime examples will be Cerasa farm, a mountain paradise which is no secret to my clients who have written rapturously about their visits (here, here, here, and here May 2012). Mario, Gemma and their daughter Ombretta are a fundamental part of a project, overseen by the Germplasm Bank set up by the Comunità Montagna della Garfagnana (now the Unione dei Comuni), to preserve the indigenous Garfagnina Bianca sheep. If you’ve noticed some sheep lurking in the foreground of a nativity scene by Giotto, it could have been this breed, which was once common in the Apennine Mountains. Mario and the dogs look after the sheep. Gemma makes pecorino cheese and ricotta from their milk. Ombretta dyes their wool with natural dyes and has them knitted and woven into saleable products. Mario rears rams to sell to other farmers who want to join him in preserving the breed. Another strand of the Germplasm Bank project is the botanical station at Camporgiano. They have rescued dozens of indigenous varieties of fruit and vegetables. Besides being grown at the station, each variety has been entrusted to a custodian, a local farmer responsible for its propagation and preservation. I visited the station last year where the Director Dr Fabiana Fiorani explained their work. In 2013 the Garfagnana submitted several apple varieties to the European Pomological Exhibition at Limoges where it gained the distinction of ‘Custodian of Biodiversity’. Watch this space for the announcement that I can take you to the botanical station followed by a visit to one of the custodians and lunch in their home. The next opportunity to visit Cerasa is during the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June. The UNESCO conference lasts for three days, during which dozens of international experts deliver research papers. It could be a big yawn, but judging by some of the titles, I for one would be awake. For example, a paper by J. J. Boersma of Leiden University is intriguingly titled ‘Could the rewilding of Europe be seen as progress?’, with the implication that the answer is ‘yes’. To me the most interesting theme is that biodiversity of domesticated plants and animals appears closely connected to cultural diversity arising from the traditions and identity of a place. Finding the balance between tradition and modernity may be the virtuous path to sustainable rural development. The mere fact of an international conference organised by UNESCO on the topic of biodiversity and sustainable development raises hope that the planet will not be entirely subjugated to the interests of agri-business. A more local, but equally important action took place yesterday, also in Florence, when Slow Food organised a demonstration against the introduction of GM corn in Italy. Fingers crossed! Find out more: Joint Programme Between UNESCO and CBD, Convention on Biological Diversity, Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe Conference programme, Les Croqueurs de Pomme

*Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, based in Montreal, Canada Participants on our Advanced Salumi Course taste a vast array of salami, prosciutto, capocollo, soppressata and other cured pork delicacies, some not so delicate. For dinner they get to try other typical dishes of the areas where the course takes place. On our first night we’re in Versilia, the northern coast of Tuscany. Gabriella Lazzarini, one of my cooking teachers and a skilled chef, lives here near Viareggio and invites us to her home for a seafood meal, which is one of the highlights of the course. Not only is it special eating in a private home, but Gabriella’s repertoire of local recipes is exceptional. She buys fish from the small family fishing boats called pescherecci that bring their catches to the molo (quai) in Viareggio. They fish off the rocks close to the coast, and the fish look strange to people who are used to seeing branzino (sea bass), orata (gilt-head bream), tuna and other large, usually farmed or endangered species served in most of the seafood restaurants here. You don’t have to enrol in the salumi course to eat at Gabriella’s home. All Sapori e Saperi Adventure’s guests can choose a meal with her as one of their activities. The other unique dining experience is on Saturday night after we’ve moved east over the Alpi Apuane to Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. We go to the Osteria Il Vecchio Mulino where our host is Andrea Bertucci, who is known affectionately as ‘Andreone’, which means ‘big Andrea’. You can see that the love of his life is food. But Andrea doesn’t cook; in fact, his osteria doesn’t even have a kitchen. Andrea is a food collector. He finds the best products in the Garfagnana, and sometimes further afield, which he serves as a tasting menu. The nearest analogy is a tapas bar, but his place is more like a hybrid of a corner grocery, wine bar and a cheese and salami maturing cellar. Since the menu depends on his latest finds, there are always surprises. In his tiny oven, not a microwave, he heats crostini and savoury tarts. There’s usually a salumi board, but I suspect we’ll be salumied-out on the course and ask him for alternatives. On a two-burner electric hot plate he warms up local specialities prepared by his mother or friends. This time it’s polenta formenton otto-file, an heirloom variety of corn, with roe deer ragù. Every time we thank Andrea and say we must leave, he produces another goodie: cinta senese salami, cured roe deer loin, fruit salad he made that very day, 15 February, which is San Faustino’s Day, the patron saint of singles. I’ve checked on Google and it’s true!

The butter is made on an organic farm from cream of cows on the farm at Cutigliano (PT) and sold in a shop 44 km (27 mi) away in Ponte a Moriano (Lucca). Delicious, especially on my sourdough bread warm from the oven (organic flour from the Garfagnana, natural leavening, sea salt from Sicily, water from a spring above my village).

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed