|

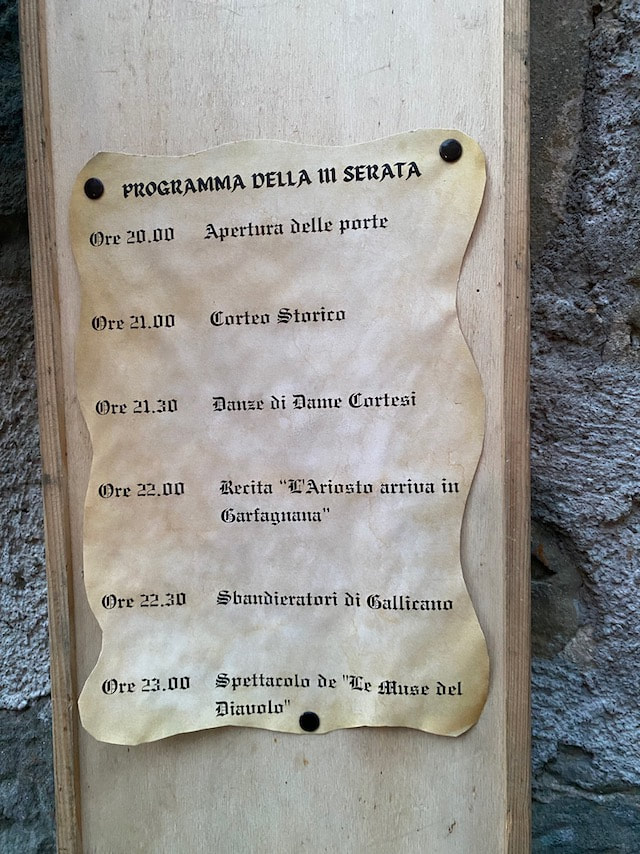

'The Bandits of Sillico in the Garfagnana of Ariosto ...at dinner time'. The translation into English of the title of this historical and gastronomic festival leaves most of the story untold. As you'll see below, the real joy is in the way this tiny mediaeval village works together to present a spectacular meal and show. But you'll need a bit of local history to get into the spirit. In the 1400s the Garfagnana (the mountainous region north of Lucca) wanted to free itself from the tyranny of the Republic of Lucca and asked for help from the Este family, the Dukes of Ferrara. The Dukes obliged and installed a governor at the region's capital, Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. In 1522 they sent the poet Ludovico Ariosto to fill the post. He hated all three and a half years he spent there, especially his dealings with the local brigands whose chief was Moro of Sillico. When Ariosto arrived, they essentially ruled the Garfagnana. Being a poet, he wrote many letters to the Duke complaining about their activities and asking for more troops, and through his descriptions we have a lot of detail about the brigands. To this day Castelnuovo vaunts its noble governor while Sillico brags about how Moro outwitted him. I know the back route to the upper gate where the queue is shorter. The entertainers are arriving too. Here's Giulio, director of the Sbandieratori and teacher of our fogaccia di Gallicano lessons, another tradition he's helping to preserve. Let me quickly brag a bit on Giulio's behalf. His troop has performed throughout Europe and is known for its fast, explosive and unpredictable style. It has won the national championships more often than any other group. Bravi! 8.00 pm—Opening of the gates 9.00 pm —Historical procession 9.30 pm—Dance of the courtly damsels 10.00 pm—Play "Ariosto arrives in the Garfagnana" (spoiler, Moro wins the poetry competition improvising in ottava rima) 10.30 pm—Sbandieratori di Gallicano 11.00 pm— Show "The Muses of the Devil" (wish I had the stamina to have stayed for this) Now we climb the steep cobbled streets to arrive at the terrace where the main course is served. This is Nadia. Her husband Bruno lights three metati (chestnut-drying huts) every October and I often take my salumi course participants to see how much work goes into producing the naturally sweet chestnut flour of the Garfagnana. Festivals are good places to meet old friends. The quickest route to the piazza where the shows take place is through Palazzo Carli where we are catapulted from the 16th century into the 19th. We come out of the palazzo to a spectacular show in the piazza in front of the house where Moro was born. We climb to the top of the village to arrive at the fourth banquet: dessert. I'll leave you with the sound of the bagpipers. Thank you to Klaus Falbe-Hansen for supplying most of the photos in this blog and to him, his wife and their friend for accompanying me for this thoroughly enjoyable evening.

2 Comments

Did history lessons make you feel that a cloud in the sky outside the classroom window was absolutely riveting? They did me. If only I could have gone to the village shop for my lessons. The shop is only 30 seconds walk from my front door. You can get almost anything there from meat to dry goods to paintbrushes, and I go every morning to buy at least some bread that comes from a village 5 km away up the valley. One morning about a month ago I commiserated with Eugenia about her ankle which she sprained while getting water at the spring up at the cemetery to wash the grave stones of her ancestors buried there. She commented that we’d had too much rain and the stones were slippery with moss. Yes, I agreed, but it was beautiful yesterday and I went for a walk down to the river, across the foot bridge and up the valley along the road to the little dam that is part of a micro-hydroelectric plant. Renato explained that it furnishes the water for the main plant at the foot bridge, which used to be a silk spinning factory. I knew that silk was one of the main sources of wealth for the Republic of Lucca in mediaeval and Renaissance times and the silk industry had only completely died out in the 1970s, but I hadn’t realised that even at Casabasciana people reared silkworms. I take my guests to visit Stefania Maffei who rears silkworms like her grandmother did and runs workshops for school children to reacquaint them with their own history. I asked where the mulberry trees were, since I hadn’t seen any. They’re mostly gone now, but Renato knew of one in a field near the little church below Crasciana (the village 3 km above Casabasciana). I mentally add that to my list of things to find. Talking about old industries, I remembered to tell them that I had just noticed the old kiln Eugenia had told me about last year, where they used to make terracotta bricks and roof and floor tiles. It’s only 5 minutes’ walk down the old cobbled mulattiera (mule track), just below where the modern road cuts through the track and above the madonnina (a wayside shrine). I’d never noticed it before, but this time I was looking from side to side for wildflowers and there were the ruins covered by brambles. Piqued by my apparent interest in building materials, Renato volunteered that there used to be a lime kiln at Crasciana which produced the lime for mortar and lime-wash used for centuries in buildings here. Actually, although I’m interested in architecture and the aesthetics of buildings, the mechanics of building have never gripped me. But now, the fact that these things used to be made right here around me, caught my imagination and when I got home, I looked up lime extraction and processing on the internet. I’m going to find out where our kiln was and and try to locate the ruins. Two days later I learned from my landlord that one of the cellar rooms of the house was the calcinaia, where they used to slake the lime when whitewashing the walls of what was formerly one of the grandest houses in the village. Everything begins to come together. Maybe that was what was wrong with history before. It was the equivalent of ‘fast travel’ — too many isolated facts without any connection to anything.

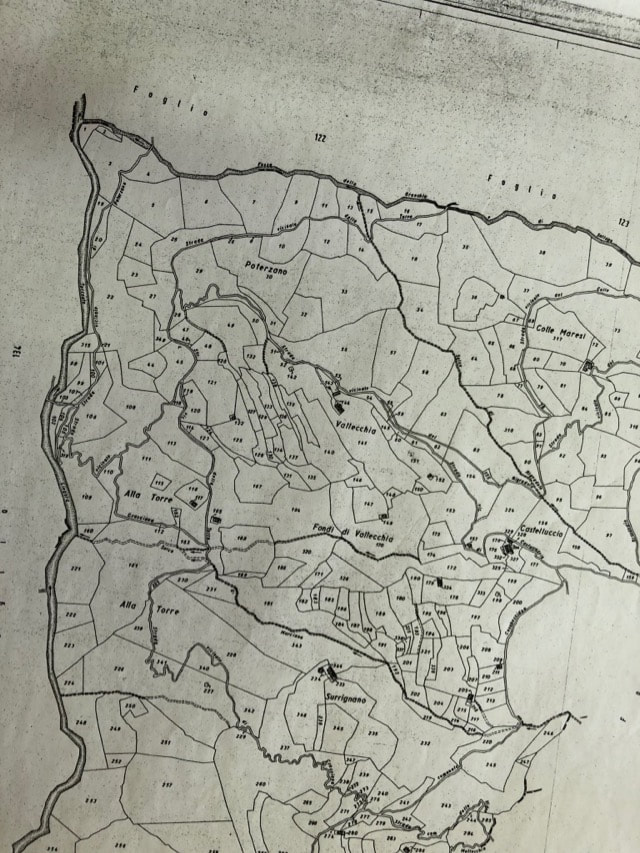

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 3 June 2012. What is it about an abandoned house that makes it so fascinating? Does it offer an escape route for our imaginations, like a fairy-tale, conjuring up fantasies of life in other times? Or perhaps it helps us feel connected to the past and ultimately to all humanity? Or maybe it’s just simple voyeurism: peeking through the curtains at a lost way of life? Whatever the reason, I felt a surge of curiosity when I first discovered the roofless casa colonica, or farmhouse, at Surignano. I approached the house on a well-defined dirt drive that cut through the chestnut woodland. It sat on the southwestern edge of a gently sloping plateau near a stream crossed by a still intact wooden bridge. I thought it must have been the house of a well-to-do landowner. The imposing stone building stands three storeys tall. At ground level two impressive arched doorways lead into the former cantinas, which would have housed animals and farm equipment. There were three or maybe four spacious rooms on each of the floors above, though the floorboards and beams are too rotten to risk exploring. Questions filled my mind. Who had built this magnificent house? And when? Who lived in it? How did they make a living? That was in 2009 before Saperi & Saperi had taken off and I still had free time to explore along woodland paths leading out from my village of Casabasciana. In 2020, the year of Covid-19, with no tours or courses taking place, I’m drawn again to explore in the direction of Surignano. It’s along what was the main road to Brandeglio, the village I can see from the windows of the upper floor of my house in the village, 2.5 km (1.5 mi) as the crow flies to the southwest across the Liegora River. This ‘main road’ was in fact no more than a footpath, because until the 1960s walking was the only mode of travelling between villages. It is still well used by walkers and maintained by men of the village and a group that uses it for an annual mountain bike event. As I walk I try to imagine the landscape 70 years ago. People have told me that all the land was terraced and cultivated with cereals, vines and olives. Everyone had a few sheep, a couple of pigs and maybe a cow or two. It’s almost impossible to visualise what it was like. I can see remnants of dry-stone walling, but not even a ghost of those numerous families working the land. My view in every direction is blocked by trees — mainly chestnut infested by acacia, brambles, wild clematis, broom and tree heather. After 30 minutes I arrive at Castelluccio, the farmhouse where my neighbour Domenico was born and brought up. It is not abandoned. He goes there every afternoon to keep the roof intact and the brambles and wild clematis at bay. It and the surrounding land give a hint of what the countryside would have looked like in the past. He arrives in his 4x4 Fiat Panda on the strada sterrata (dirt road) that descends from Crasciana, the village above mine. I often find him there if I stop to drink the icy cold water his grandfather piped in from a spring higher up. I cross that road and continue southwest towards the Liegora River, now on another strada sterrata suitable for a 4x4. I pass a couple of crumbling buildings that must have been either metati (drying houses for chestnuts) or sheds for storing equipment closer to fields. Another 10 minutes and I reach the road that I remember leads to Surignano, but I’m sure I need to take a fork off it to the left. Now I notice that a logging operation has cleared a huge swathe of land and, I presume, erased the former drive and destroyed the neat terracing. Continuing straight I come to log piles surrounded by carpets of spring flowers. I find the old wooden bridge, now nearly invisible and decaying under velvety green moss. Finally, dropping down through a thicket of birch saplings, I emerge behind the house. Struggling around to the front the façade shocks me, like seeing a friend after 11 years, so much older, greyer and wrinkled. What a story this house must be able to tell! Layers of history of the land and the people who lived here. But it is mute, sulking after decades of neglect. By now my Italian is up to asking questions of my neighbours in the village. At first they aren’t very interested, but the few clues they throw me are more tantalising than having the whole story land in one indigestible bundle on my doorstep. – Have you found Cerro? It was even more beautiful than Surignano. –You know, my mother Olga lived there. –The forestry commission planted that ugly fir tree plantation without even asking the owner’s permission. –Did you see the church San Martino on the way? On the left, diagonally across the corner. Only a part of the façade is left. It’s from the 8th century. – My grandmother lived at Lupinaia. I often walk out to look at it. –It’s been restored, by a family perhaps from Ponte a Moriano. But it belongs to the frazione of Crasciana, not Casabasciana. –I heard that the wife doesn’t like it, so they hardly come anymore. –There used to be a path opposite the Croce del Bacco that led to Collemaresi. –You can also get there from just before the path crosses the Rigrado stream, but it’s probably blocked by brambles. –Go straight down from the Metato di Bacco to the three pine trees, and then straight down another 100 metres. You can’t miss it. Here, I’ll show you the pine trees from my gate. –Memmo Nardi lived there. His grandson Guglielmo still comes to Crasciana every winter. –Vallecchia is below Castelluccio. –The Logi family were contadini there but they moved into the village in the ‘50s. –Someone took me there once. If I can remember the way, I’ll take you. One by one I found all six farmhouses and their attendant outbuildings. All but Castelluccio and Lupinaia are knee-deep in brambles and wreathed in ivy and wild clematis, all partially collapsed. They were built in the 1780s. All seem to speak of a prosperous past, but now I know that the prosperity was mainly that of the landowners. Apart from Domenico and his family who owned Castelluccio, the inhabitants were tenant farmers paying rent, usually a percentage of the produce, to the owners. Their descendants tell me that Collemaresi, Cerro, Vallecchia and half of Surignano were owned by the Finucci family, who lived in the grand house opposite the one I rent in the village. They are gone too. The houses were large because families were large. Typically couples had 5 to 8 children. When sons married, their wives came to live with them in the family home, and grandchildren swelled the head count. Jobs on the farm were numerous and required many hands to plough, plant, prune, harvest, care for animals, make cheese, slaughter the pig and cure the meat, cook, clean, weave, sew, cut firewood, maintain buildings and equipment. But it wasn’t all work. In the long winter evenings they would gather round the kitchen fireplace for the veglia, storytelling and playing games. In addition to the houses themselves, there is the network of mulattiere (mule tracks) and paths that connected them to each other, to sources of water and to villages with shops, schools, markets and craftspeople. They reveal social and economic relationships. Domenico showed me a set of cadastral maps in the ex-schoolhouse, documenting land ownership around the village. I asked our village president to have them scanned so I could study them. Unfortunately the plots of land are identified only by numbers, and I don’t have the key to who owned each one and how ownership shifted. But on them you can see the old paths. Trying to find them in the woods is a gloomy task, and highlights how inadequate are the number of able hands left in the village to maintain them. During every storm trees come down blocking paths, landslides cover others, cobblestones wash out, people no longer use them, boar and deer find other routes, acacia and broom colonise the abandoned tracks. Most of the villagers are more realistic than I am. They know maintaining the countryside as it was would be a series of fruitless battles lost to the inexorable forces of nature. But occasionally my curiosity has inspired someone to recover the past. We now have a WhatsApp group called Casabasciana in Storia (Casabasciana in History) where people occasionally post information and photos from the past. One day I asked Giovanni how the people at Surignano and Cerro got their water. He told me there’s a spring halfway between them with a lavatoio (laundry), but I couldn’t find it. Then suddenly a couple of days later, he posted a photo of it to the WhatsApp group. He had gone out and cleared the brambles, and described to me exactly how to get to it. Many of the farming activities are ones you learn about first hand on my tours and courses, because I’ve found people who, with a bit of mechanisation and marketing, are still making mixed farming pay at the family level. But it’s more difficult now. That’s partly because almost no money was required right up until the 1960s. Farms were self-sufficient. There was very little that needed to be bought in. But after the war, in the ‘50s and ‘60s the introduction of the internal combustion engine catapulted subsistence farmers into the cash economy. They needed tractors, cars, chainsaws and the petrol to run them. They could no longer repair everything themselves, so they had to pay for expertise to keep their machines running. Finally, agribusiness dealt a mortal blow. My next blog will mourn the death of all but the most resilient small family farms.

I go with Marco on the way home from the mill. It turns out he’s from Saltocchio, the village on the way to Lucca that Alberto, who is not from Saltocchio, told me took its name from from a battle there in which one of Hannibal’s elephants had lost its eye (‘saltare’ means jump and ‘occhio’ means eye). Marco’s legend is completely different. There used to be a small lake in the shape of an eye in front of the church and a boatman ferried worshippers across to its door, hence ‘jumping over the eye’. In a couple of hundred years will people wonder why a particular spot on the South Bank of London is called ‘London Eye’?

Franca gets to the community hall at 7.30 every morning to sort chestnuts. When I arrive around 9.00 there are already four family members around the table. Now that I’ve discovered the therapeutic value of talking, I decide to find out more about them. There’s Olga who is 85 or 86. I think of her as Domenico’s mother, rather than the other way round, because she lives in her son’s house, opposite mine, with him and his wife Ebe. Olga walks with a stick, which seems totally unnecessary to me. I met her once coming along the woodland path from Castelluccio, the farmstead where she raised her family, which is a brisk 45-minute walk from our village. Her stamina at the chestnut table is unbeatable, and her speed and accuracy of sorting puts the rest of us to shame. I reckon she could do all 24 sacks of them as quickly by herself and she just tolerates us to make us feel needed. I ask her whether anyone is living at Castelluccio now. No, no longer, but they used to cultivate all the land there. She doesn’t sound sad or nostalgic. Times change, and it wouldn’t be practical to live there now. Then I ask about a couple of houses farther out, one of which has recently been restored. Do I mean Lupinaia? Well, I don’t know. I didn’t know every house had a name. Someone asks whether I discovered Surignano. The house with the beautiful Roman arches? Some English people bought it a few years ago, but never restored it. They think they bought it on the internet and when they arrived and saw the state it’s in, abandoned in the midst of the chestnut wood, they lost heart. The others now start throwing names into the ring and try to describe to me where they are — houses, churches, water mills, streams. The conversation becomes animated. Names are repeated, rolled around in the mouth to recapture the flavour of them. Each place is like a family member with its own personality. The landscape is a patchwork of names. Nowhere is omitted, nowhere is nameless wilderness.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed