|

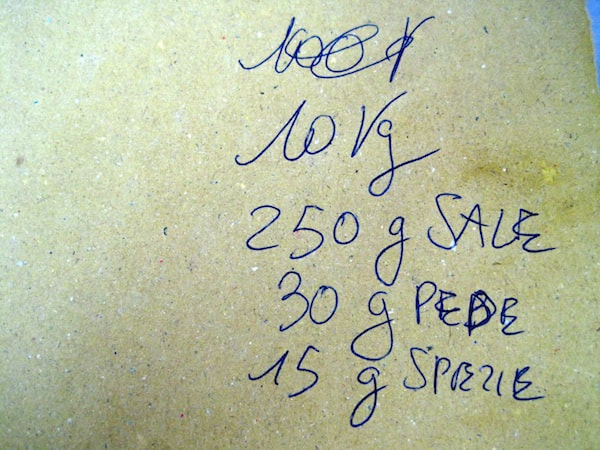

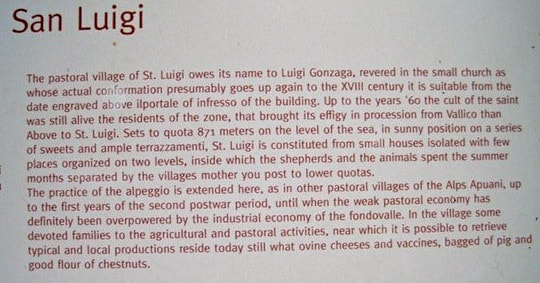

I spent from last Thursday to Sunday elbow deep in pork: whole pig, half pig, shoulder of pig, belly of pig, leg of pig, trotters, back fat and heads of pig. It was the fourth Advanced Salumi Course that I’ve organised for professional pig breeders, chefs and butchers, as well as keen amateurs. I never realised how many closet salami makers there are out there. Thursday afternoon we begin with a 3-hour introduction to salumi, the Italian word that describes the whole exquisite array of pink, red and white cured pork that adorns the counters of Italian delicatessens. This theoretical session is given by Giancarlo Russo, co-author of the Slow Food guide Salumi d’Italia and consultant on meat to Slow Food Italy. He designed the course for me and helped me find the norcini, specialist pork butchers, who teach the hands-on sessions. Thursday evening we have the best meal of the course at Gabriella Lazzarini’s home. She loves to cook seafood dishes and buys her fish from family fishing boats at the pier in Viareggio, near Camaiore where we stay the first night at the beautiful Villa Lombardi. This time she has prepared four antipasti including an unbelievably delicious stewed squid on creamy polenta. The first course is homemade pasta with a red mullet sauce followed by two second courses, of which one is the typical frittura viareggina, fried mixed poor-man’s fish. Since it was live and jumping at 8.00 am that morning, each fish has its own intense flavour. We barely have room for the fresh winter fruit salad with wild blueberries preserved in alcohol, but we manage to stuff it in nevertheless. Friday morning we head to Massimo Bacci’s butcher shop and salumi laboratory in Montignoso. Massimo clearly loves sharing his craft with other people. He starts by teaching us which cuts of pork go into sausages and which into salami. He shows us how he grinds the meat; he shares his secret spice recipe with us and shows us how he infuses wine with garlic to add to the ground pork. We learn how to massage the meat and everyone gets a chance to try it. Like kneading bread, it takes practice to get the right movement of palms and fingers and to make sure all the meat gets to the right stickiness ready for stuffing into sausage or salami casings. Occasionally Massimo’s 81-year-old father pokes his head through the door in a lull between customers and corrects his 60-year-old son in something he’s demonstrating. Filling the casings is called insaccati in Italian, literally putting meat into sacks. A sign I found in the middle of the countryside gives the creative translation ‘bagged of pig’. Tying sausages the Italian way is a challenge. So as not to make a fool of myself, I usually watch and help Giancarlo interpret (none of the norcini speak English), but this time I had a go and didn’t do too badly. Everyone falls in love with the natural hemp string used, and my carry-on allowance on Ryanair is often used up taking it back to England to post to former students. The next nearly insurmountable challenge is tying salami. It has to be tight enough to press any remaining air out of the salami while not cutting the casing. Massimo has an elegant way of doing it, and under his patient tutelage everyone finally produces their own adequate example. Now we see the salami drying cupboard. Massimo uses a programmable one because he doesn’t have the ideal natural conditions to achieve 100% good results. After about 7–10 days in the cupboard, he moves the salami to a partially underground room with some ventilation. He can control the temperature and humidity, but rarely has to. Now the salami is left to mature for a minimum of two months for the small ones and a lot longer for the larger ones. It’s not an exact science, and Massimo pinches the salami to determine whether it’s firm enough yet. Eying his maturing salami, I imagine Massimo feels like I do when I’ve made a batch of marmalade and I gaze at the rows of gleaming jars. We still have more to learn from Massimo. He shows us how he hangs small cocktail sausages for 5–7 days for a wine bar that serves them raw as an antipasto. In fact, in Tuscany we all eat raw sausage, usually spread on crusty country bread. Pigs don’t have trichinosis in Italy, so it’s perfectly safe, but the idea doesn’t appeal to English and American participants. Bravely they taste a tiny bit and as soon as they find out how good it is, they always come back for more. Massimo’s other product is lardo, cured pork back fat. Massimo lives just below the marble quarries of Colonnata, renowned for its lardo, and he too packs his slabs of fat seasoned with salt, pepper and herbs into marble ‘coffins’. One is dated 1896. I read that when Mario Batali started making and serving lardo in New York, his waiters asked him what they should tell customers when they asked what it was. They were sure no one would order it if they said it was pork fat. Batali told them to say it was ‘white prosciutto’, and it seems to have worked. I ask people whether they eat butter on bread; a fine slice of lardo is no more fat than that and tastes just as good. By now it’s lunch time and we get to taste all Massimo’s salumi. The bread is a traditional sourdough made only at Vinca in the Lunigiana. Since Massimo is a wine connoisseur even the wine is special and different for each course. We buy some salumi and reluctantly tear ourselves away to get to our afternoon session with Fabio Nutini, a subject for another blog.

0 Comments

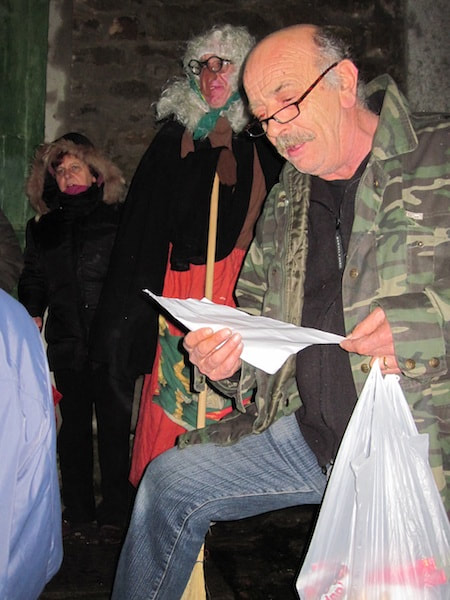

The Befana is a good witch. She arrives on her broomstick on 5 January, the eve of Epiphany, or Twelfth Night. She goes from house to house, accompanied by villagers singing a begging song. In Casabasciana she brings presents for good children and lumps of coal for bad ones. Adults receive a present too, in return for which they make a donation to the upkeep of the village church, and the end of the song thanks them for their gift. It’s interesting that an apparently pagan character is willing to handover her takings to established religion. In some villages in the Garfagnana there is a tradition of the Befana being a cross-dressed man. We run an equal opportunities policy; last year a woman dressed up in the costume, and last night a man played the role. Besides the broom essential for locomotion, a large nose, glasses, a wild wig and headscarf are de rigueur. The evening begins at about 8 pm when the men gather in the bar and the women take the befana-to-be to the village hall to dress him or her. When they emerge everyone sets off on a zigzagging route stopping at each of the inhabited houses of the village. It’s misting gently, but if traditions are to be preserved, one mustn’t be put off by a little rain. At each house we sing Casabasciana’s begging song (each village has a different one and, yes, it’s a bit boring after the 20th time) and deliver presents, different ones for girls, boys and adults. All the children of Casabasciana must be good, since no one receives a lump of coal. Did anyone consult their parents? Ancient hilltop villages abound in nooks and crannies that invite decoration. Outside Margherita’s house, at the top of the village on the site of the original fort, is a charming little presepe. By 10 pm we’ve reached Angela’s house where we’re welcomed to refreshments. Angela has baked befanini and cialde, both of which are typical here for the night of Befana. Befanini are simple biscuits, cookies decorated with coloured sugar sprinkles. Cialda means wafer. Here they are flavoured with anise seed and rolled into cones. Anna Rosa makes hers the old-fashioned way, baking them between patterned iron plates heated over a flame. Angela has a cialda machine. I wonder if I could tell the difference in a blind tasting. Some bottles of fizz are uncorked, the donation box is opened and the grand sum of €380 is declared. Satisfaction all round, since the take is better than last year despite the economic crisis, someone observes. By 11 pm a happy glow follows us as we depart for our own houses.

Even though most of us are back at work and it feels like life as usual, today is only the tenth day of Christmas, which continues for twelve days from 25 December, ending on the 6th of January, Epiphany, when the Magi arrived at the stable to shower the Baby Jesus with gifts. Here in Italy presepi, reconstructions of nativity scenes, are still on display. As I went to see them in tiny villages and small towns, I thought of the community spirit and individual skills needed to produce these complicated constructions. The Media Valle del Serchio (just north of Lucca and including Bagni di Lucca) is renowned for its gesso (plaster of Paris) figurines, many of which were cast to be used in presepi. Presepi come in all shapes and sizes. Many are in churches or church halls and show the artist’s conception of every day life in Bethlehem, like this one in the church at Pieve Fosciana in the Garfagnana. At first, I was enjoying the treasure hunt too much to take photos and missed the one in the chimney pot, but here are some others. Sometimes a whole village is turned into a presepe vivente, a living presepe, where attic’s are ransacked for pre-war clothing, children write on slates in candlelit schoolrooms, woman sit on rush chairs doing their tatting, wine is mulled over a fire in the street and at midnight real parents bring their infant, usually dressed in Baby Gap jeans, to the manger at the base of the fort at the top of the village. The most inventive presepi are the miniature ones in the church hall at Pieve Fosciana. Several have moving parts, most include music and one of the Annunciation shows the angel Gabriel magically appearing and disappearing, which I totally failed to capture in a photo. The prize for the kitschiest must be this one in a piazza in Lucca.

It’s the custom at midnight at the New Year’s Eve dinner in Casabasciana to pop open the spumante, take a gulp and then get up and greet everyone with ‘Auguri! Buon Anno!’ and a kiss on each cheek. At my first New Year’s Eve dinner in Casabasciana, there were three or four generations present. Now the younger people have their own party with loud music. We oldies prefer good food and conversation. We’ve agreed an amicable devolution. Appropriately, our dinner is in aid of an old people’s home, an ancient building overlooking the car park that’s being restored as and when there’s enough money for the next phase of construction. The exact time of starting dinner is never fixed. Even at restaurants, you just say you’re coming for lunch or dinner. They don’t ask what time. Tonight it’s not before 8.30, so we congregate in the bar near the community hall to be ready to strike when summoned. I stop on the way to the bar to check on progress in the wood-fired oven… …and in the kitchen. We take our places at the long trestle tables and the courses arrive in leisurely fashion. First, the antipasti misti, an assortment of crostini and, on New Year’s Eve, there are always lentils. Being round, they symbolise the cycle of the years. My favourite is the thin focaccia with lardo. Next two primi: I can’t resist seconds of the maccheroni. As you can see, it’s not elbow macaroni, which is a southern Italian pasta; instead it’s simple squares or rectangles of handmade pasta. Then two secondi. The hunting squadron donated a couple of wild boar as their contribution to the old people’s home. They’ve shot 173 since the season opened on 1 November. This one is young and tender. The other secondo is roast beef, medium rare and thinly sliced. Someone has a 60th birthday. A specially commissioned poem is recited and the birthday cake arrives. In addition there are cialde (more about these on Befana, 5 January) and clementines. At 11.45, a couple of the younger generation arrive, get the sound system going and insert a tango CD. Obviously they think us oldies can’t manage the DJ side of things. Usually we don’t have fireworks, but this year, the youngsters surprise us with a display in the piazza. Hugs and kisses and auguri to all!

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed