|

I first thought about the power of water when Bob Coleman, my tai chi teacher and director of works at Neal’s Yard Dairy (there’s always a food connection), was trying to get us to comprehend the force behind one of the moves in ‘grasp sparrow’s tail’. Water isn’t compressible, it doesn’t give when it hits you. We practised sending all our energy to our forearms and not budging an inch. While I was editing the World Bank’s independent review of the Narmada dam project in India with social anthropologist Hugh Brody, I became aware of the power of water to disrupt traditional communities. Moving to the valley of the Lima River, a major tributary of the Serchio (pronounced serk´-ee-o) River that flows across the Lucca plain and into the sea just north of the Arno brought me closer to the power of water. As you drive up and down the valleys, you see everywhere the evidence of the power of water to generate electricity through micro-hydro plants. It’s impossible to imagine what the Serchio was like before dams were built on every tributary and the main river itself, and huge tubes were drilled through the mountains between the tributaries so that water can be shunted to whichever reservoir needs it most. I’ve read that it was navigable, which it certainly isn’t today. One theory for the unequal heights of the arches of the Devil’s Bridge is that the masts of sailing ships had to fit through one of them. In mediaeval times the river (then called the Auser) progressively flooded land nearer and nearer to Lucca. Luckily, the Bishop of Lucca San Frediano, an Irish priest, was also an expert hydraulic engineer, and put a halt to the flooding by moving the course of the river to its present channel in 561 to 589. It takes a long time to move a river, but it did the trick. The Lucca plain is still crisscrossed by drainage canals to stop flooding and create rich arable land. Once or twice every winter due to a particularly heavy rainstorm or snowmelt, the Serchio is in spate. The swirling drive of the water is almost intoxicating as it fills the whole river bed and churns the worn river stones gouging out unfortified stretches of the river bank and piling up new pebble islands that will be visible when the water recedes. Occasionally it floods the main road at the Devil’s Bridge, just upstream from the big dam at Borgo a Mozzano, the last bulwark where the amount of water flowing across the Lucca plain can be regulated. Usually the most annoying damage is a few small landslides (frana in Italian) that either undermine or block the narrow mountain roads connecting the main road along the valley floor to the ancient villages high on mountain ridges. As I write this it’s been raining hard, really hard for five days in the Province of Lucca (probably elsewhere too, but what’s local has most impact). There’s an occasional break of a few hours, and then the rat-a-tat of the drops starts again. The force of the water in streams, rivers and canals is destroying roads, houses and fields. There are many more landslides and trees lose their grip and topple over also blocking roads. Although I didn’t ask for them, my computer gives me FaceBook updates from the Provincia di Lucca. In the last 24 hours they’ve been coming through nearly as fast as the raindrops. 24 hours ago #maltempo [bad weather]: The level of flow of the Serchio remains constant. The major danger remains the network of drainage ditches on the Lucca plain. #maltempo: Road maintenance crews from the Province removed detritus from the road at Acquabona (Castelnuovo Garfagnana) on the SR455. They positioned protection blocks. The road is open. #maltempo: On the strada provinciale 37 of Fabbriche di Vallico (locality Lombardo) in course of removal of detritus and water issuing from an adjacent ditch. Light inconvenience but the road is passable. #maltempo: In locality Ripa (comune of Seravezza) the eponymous river overflowed because of an obstruction of the river course caused by a landslide. Two houses are flooded. The comune sent its own volunteers to protect the houses and sent the Consorzio di Bonifica [land drainage] Versilia Massaciuccoli to remove the obstruction from the canal. #maltempo: The water flow at the dam at Borgo a Mozzano at 13.00 was 600 to 700 cubic metres per second. [I hope the Devil’s Bridge is holding strong. It’s over 1000 years old.] 21 hours ago #maltempo: Engineers are constantly monitoring the situation of the #serchio. #maltempo: The frazione of Tereglio is cut off due to two landslides which fell on the SP56 and on the SC Tereglio–Lucignana. #maltempo: A rise in the level of the #serchio has been registered. 15 hours ago #maltempo: A night of work for the personnel in the operations room for civil protection in the Province of Lucca. Many and diverse emergencies caused by the strong rain. At daybreak visits to the places are planned to assess the landslides and flooding. 14 hours ago #maltempo: In the comune of Gallicano, the frazione of Fiattone is reachable only by 4×4. The road was affected by a landslide. [Just below Fiattone is Podere Concori where Gabriele da Prato makes excellent wine. Are his terraces being swept away?] #maltempo: SP60 from Pascoso–Pescaglia remains closed due to a landslide. Road maintenance crews are working at the site. Pascoso continues to be unreachable. [A comment 5 hours ago: It’s still closed.] 13 hours ago #maltempo: Transit barred by a landslide on the comune road Mulino di Burica, in frazione Fabbriche di Casabasciana (comune Bagni di Lucca). At the moment one house is cut off. [It’s getting closer. That’s at the bottom of my hill.] #maltempo: A landslide has closed the road to Sillico, comune of Pieve Fosciana. [How will Ismaele, one of the norcini who teaches my Advanced Salumi Course, get up there to feed his pigs and cattle?] I feel anxious. What will be next? It feels like the world around me is crumbling, washing back to the sea where it came from. 12 hours ago #maltempo: The comune road to Bargecchia (Pieve Fosciana) was rendered impassable by a landslide obstructing also the road to Capanne di Bargecchia. The two communities are cut off, reachable only on foot. Work has already begun. #maltempo: The road to Sillico in the comune of Pieve Fosciana previously interrupted by a landslide has been reopened as an alternating one-way system to ambulances only. [Will they feed Ismaele’s pigs?] #maltempo: Worrying the level of Lake Massaciuccoli which has reached 48 cm. It is continually being monitored especially in the vicinity of Massarosa. #maltempo: In locality Lombardo, in the comune of Gallicano, a landslip is affecting a high tension electrical pylon. ENEL [electricity company] is assessing the situation. 11 hours ago #maltempo: After the peak flow during the night of 1100 cubic metres per second, the flow of the Serchio at 7.00 am was down to 950 cu.m/sec. The levels are being constantly monitored by the Province’s engineers. 3 hours ago #maltempo: President Baccelli [President of Lucca Province] inspects the SP56 in the Valfegana. [That’s the road to Marzia, one of my cheesemakers. Good thing they’re almost self-sufficient.] Gradually the reports bring better news; roads have been partly opened and dikes repaired, but some people have lost their houses. President Baccelli has asked for financial assistance from the Tuscan region. In one of the gaps in the rain, I go out to investigate whether Casabasciana has suffered any damage. I’m relieved to find that all the houses and roads are intact. Mediaeval town planners had the good sense to bed their villages on solid rocky spurs high above the valleys that were subject to flooding. The cobbled streets slope toward the centre where the water gushing from downpipes from roofs coalesces into mini-rivers that flow downhill out of the village. I think of the people swept away by tsunamis and major floods. We’ve escaped lightly, this time.

0 Comments

You never know what you’ll find at an artisan cheesemaker’s in Tuscany. I’d been meaning to visit I Taufi farm for several years, and finally made it last summer. I’m no longer surprised by the superwomen I meet at these farms, but Daniela Pagliai is exceptional, and I’ll tell her story another time. In her farm shop, there was a shelf of pamphlets and leaflets. I took a selection to read at home. One turned out to be about a village woman, born in the late 1800s who improvised verses in ottava rima as she worked and in the evenings around the kitchen fire. I thought improvising poetry was a dead art; something troubadours did in the Middle Ages. Yet here was a woman who was doing it during my lifetime, and she hadn’t even gone to school. I did a little research on ottava rima and discovered that it has been traced back to Bocaccio in the 14th century and so may have originated in Tuscany. Interesting, but then I forgot about it.

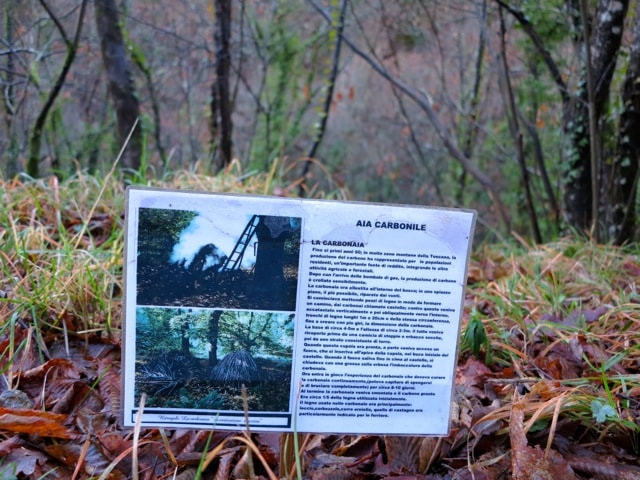

On Tuesday last week I received an email from Stefano, the owner of Il Mecenate, one of my favourite restaurants in Lucca, announcing four classes on the improvisation of ottava rima taught by a master of the art Mauro Chechi. A native Tuscan born in the Maremma, he trained in jurisprudence (another improvisatory art?), but gave up practising in 1979 for a life in the theatre. [youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTBbbTgL5T8[/youtube] The lesson took place at the headquarters of the Partita Democratica* in Piazza San Francesco in Lucca. When I arrived at the bleak shopfront, after dinner next door at Stefano’s, there were about a dozen people milling around in the unheated room, lined with 1970s tongue-and-groove knotty pine wainscotting above which hung framed black-and-white photos of past party luminaries. The furnishings consisted of a long formica-topped table and green plastic stacking chairs. The class was billed to begin at 9 pm, and Mauro tried to start at about 9.15, but people kept trickling in until 9.30. In the end 18 men and women, old and young, stylishly dressed and carelessly clad were assembled. Many seemed to know Mauro and all had some acquaintance with ottava rima. Since I wanted to blend in, I didn’t take any photos or videos. One Italian who did got the evil eye from those around him. Mauro told us that ottava rima is still practised in several regions of Italy including the Abruzzo, and there are practitioners in most of the countries where Romance languages are spoken. It’s particularly easy to improvise the rhyming scheme when many words have the same endings. It’s much harder in English, although some English poets have used it, a famous example being Byron’s Don Juan. Each verse has eight lines of 10 or 11 syllables with a rhyme scheme abababcc. The rhyming sounds at the ends of the lines are the anchoring landmarks that permit you to improvise, acting perhaps like chord sequences for a jazz musician. After giving us a couple of examples, Mauro started going round the room asking each person to try it. Some people had obviously done it before. The youngest, a man in his 20s, was particularly adept. I was relieved that some people declined, as I did when it came my turn. I wondered whether the woman next to me wished I hadn’t attended, when Mauro asked her to improvise on the theme of the English visitor! But she made a good job of it and shook my hand warmly when I left. Some people wanted to go away and practise at home before trying in public, but Mauro said they’d never get better unless they practise with an audience. One man who excelled advised that you have to sing it in order for the words to come easily. If you’re wondering why this is in my blog which is usually about food and gastronomic tours, then you’d better ask Slow Food who made this video at Slow Folk 3. [youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P5pbPEubmJ4[/youtube] Only a few kilometres from Daniela’s farm this ottava rima show recently took place to a packed hall. The audience was having so much fun, it could have been a stand-up comedy routine. I couldn’t tear myself away, even though I only understood scattered words. [youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbUdwjrK3Kc[/youtube] I probably won’t pursue the art any further myself, but I feel a world where people still have fun improvising in ottava rima is a better place to live. *Centre left party whose member Enrico Letta is the current Prime Minister of Italy. Is it better to visit the Presepe in Grotta (nativity scene in a cave) during the day or at night? We puzzle over this at lunch, which, as usual in Italy, goes on so enjoyably and so long that it’s dusk when we arrive at the bottom of the trail. The way is lit by a string of low-energy lightbulbs, which is just as well, since the trail is not for the faint of heart. When we finally reach the cave, our guide Stefano has no doubts that the only time to make the pilgrimage to the presepe is in the evening when you follow the lights, mimicking the Magi who followed the light of the star. I put this to the test when I come with other friends the next morning to repeat the journey in daylight. This time I’m more relaxed, not worried about getting to the cave before the rough, steep path disappears in shadowy gloom. We take time to appreciate the work put in by the speleological club, which had created a detailed nature trail along the path. This sign reads: ‘Botanical path. Le Campore: 600 m. Respect the woods. Wear hiking boots. Keep dogs on a lead. Carry an emergency lamp. Thank you for your patience’. Even at 11 am Carlo Galgani’s forge is in the shade. For three months during the winter the sun never reaches the bottom of the valley. The steps up to the cave at 600 meters are steep and uneven and were more than a little scary in the gloom of dusk the night before. The walk itself is an education. Trees and plants are identified along the way. Here we learn that around Lucca you’re allowed to forage for wild asparagus only between 10 February and 20 May, and each person may pick just thirty spears a year. This might be another activity to add to the foraging weekend I’m developing. Cultural history makes its appearance along the trail too. This sign explains that in the past there were many charcoal burners in the area. Carlo the blacksmith still uses charcoal from one of the few remaining charcoal burners. I’ve been meaning to try to visit him to find out whether I can bring guests to watch the process. As we near the cave, the trail gets even more arduous, but a laughing waterfall cheers us up the last set of rickety steps. Within the cave are pastoral tableaux staged with gesso figurines. Their manufacture made the fortune of many artisans in the Serchio Valley from the seventeenth century until the second world war, and their trade carried them as far afield as Scandinavia and Brazil. A family in my village still manufactures them, and I’m reminded that they offered to show me their small factory at the bottom of the hill, which I still haven’t gone to see. So many riches still to investigate. No one remembers bagpipes in this area. Perhaps this shepherd comes from the Abruzzo. Marco is on duty as the daytime guide. He tells us all the facts about the cave in a torrent of words with a flurry of hands. He says Stefano is the poetic guide and he’s the practical one. The cave has only one opening and slopes steeply down to an emerald lake at the bottom which is 7 or 8 metres deep in winter. There’s no life in it at all. Back outside Marco explains that all the gear has been ferried down by the cable car from the dirt road above the cave. We take this even more precipitous path up to the road, which we follow gently down to the valley and our car. The evening before we descend carefully down the lighted nature trail with some Italians who repeat rapturously, ‘Suggestivo, veramente suggestivo’; the English ‘full of atmosphere’ sounds lame, perhaps ‘charming’ or ‘romantic’ conveys our impressions better.

When I think of seasonal eating, I usually think of what’s available from my orto (vegetable plot), fruit trees and local farms at a particular time of year. But there’s another kind of seasonal eating: the traditional foods that help us celebrate holidays and rites of passage. In Tuscany and more especially in the Province of Lucca, this is the time to eat befanini, a simple biscuit or cookie. The name comes from ‘Befana’, which in Italian derives from ‘Epifania’, or Epiphany in English, which in turn comes from the Greek verb meaning to appear. The date is always the 6th of January, the twelfth day of Christmas, the day with all those Drummers Drumming, but also the day when Christians celebrate the ‘Incarnation of Jesus Christ’ and the arrival of the Magi in Bethlehem bearing gifts. As far as I can discover, the Befana, a witch who travels around on a broomstick taking presents to children on the eve of Epiphany, is particular to Tuscany, and especially to the Province of Lucca. It’s first documented in the 13th century. [January 2019: my original source for this has disappeared from the internet. You can find other theories on Wikipedia.] Americans will immediately wonder how this little old witch became associated with Halloween, or vice versa. If anyone has the answer, I’d love to know. The befanini of Barga are the most elaborate I’ve seen, truly works of art. My friends Francesca (who created the befanini above) and Marta explained to me that these biscuits were made by peasants to offer to the Befana when she visited their farms. In an agricultural economy with little cash, sugar was scarce and only used for special occasions. Besides the sugar, the befanini acquired extra value by virtue of the labour lavished on their decoration.

In my village of Casabasciana we celebrate the Befana in the traditional way, which you can read about in my blog: The Good Witch Befana. One of the most satisfying things about celebrating with locals, is that you always learn something new. When I wrote that blog two years ago, I hadn’t been educated by Francesca and Marta. Perhaps the Befana isn’t a pagan character after all, and now I realise that giving money to the Befana is an innovation, a way of monetising the custom. But I suppose you can’t repair the church bells with befanini. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed