|

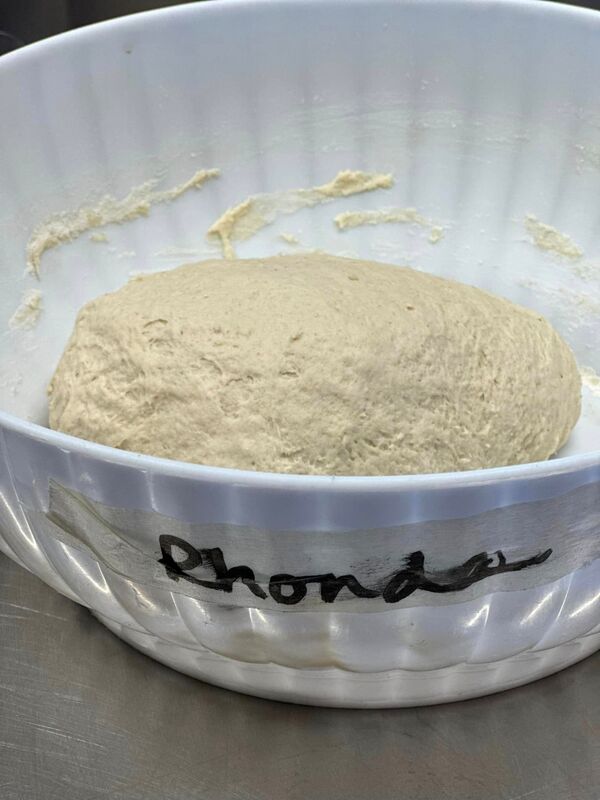

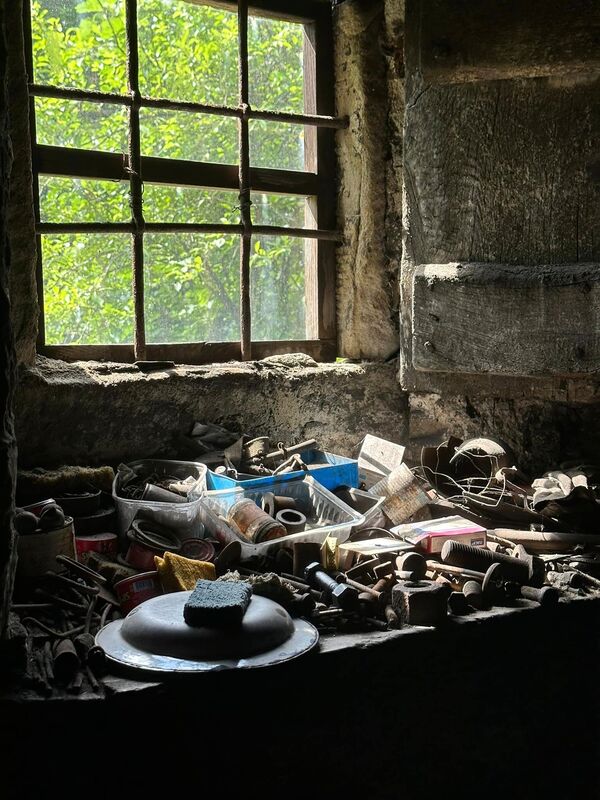

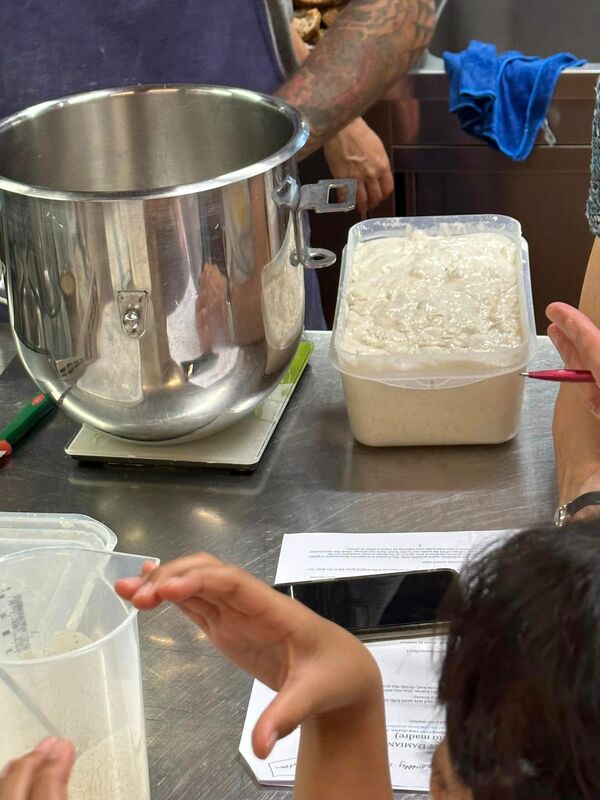

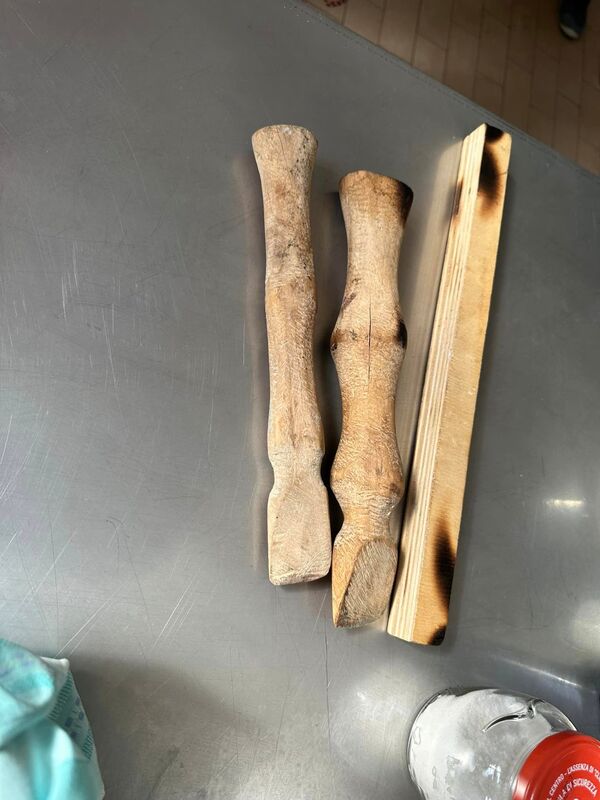

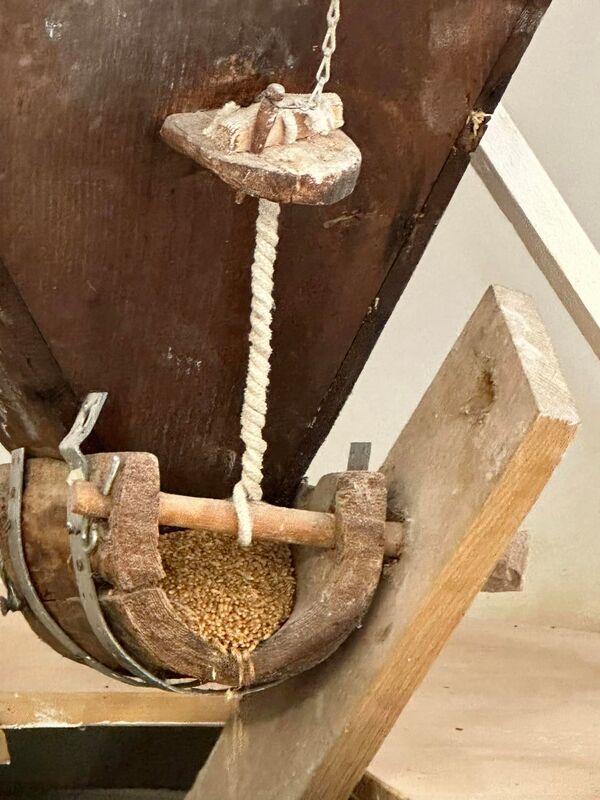

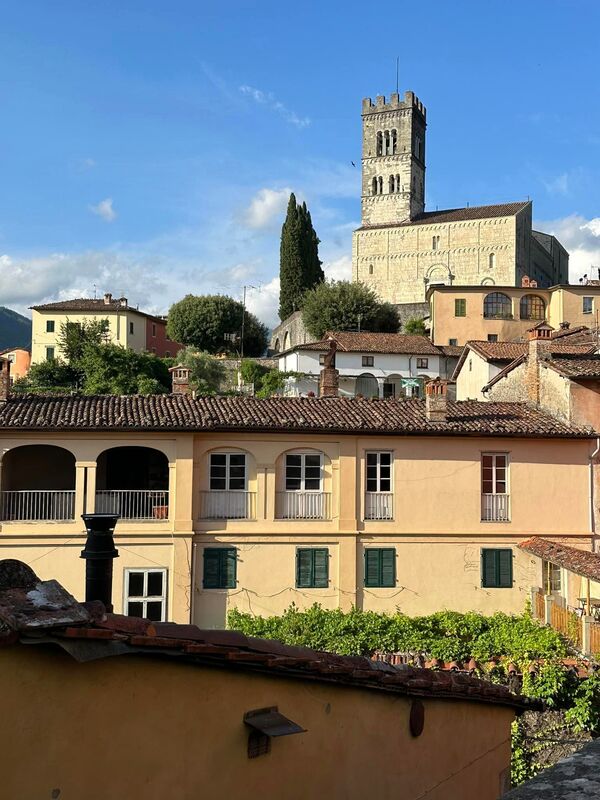

Rhonda Gothberg, a goat farmer and cheesemaker from Washington State, USA, joined us on the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany this year. She shared wonderful commentary and photos online during the course and has allowed us to share them with you in this blog post. We have put together her comments and photo captions below. Enjoy! First a note from us: Rhonda had travelled around Italy before joining the course, which began in Hotel Park Regina, Bagni di Lucca.  Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Sourdough bread making today with Chef Damiano at Fattoria Sardi. We were also treated to lunch there. We go back tomorrow to bake the bread and another lunch. Oh my goodness...all around excellent. A highlight today is a visit with Carlo. He’s 85 years old. His family has been blacksmithing for over 500 years. Sadly, no one is coming up behind him. This place is fascinating! It is run completely on water power. Such a skilled master artisan. We were all mesmerized. Today we worked with Chef Damiano again and got our bread baked from yesterday. We then had a tour of Fattoria Sardi vineyards and wine areas. We learned to make our own sourdough starter. Then another fabulous lunch. After that we visited a farmer who grows ancient varieties of wheat. A brief rest at the hotel then out to dinner for pizza and a beer. We learned to make these yeasted flat breads [Ed.--fogaccia leva di Gallicano] yesterday. These are made on traditional flat iron sort of griddles. Some call the pan testi but there are other names [Ed.--cotte in Gallicano] depending on the village tradition. Our hosts have been best friends since birth. What a duo! The ensuing lunch with this traditional food was really good. It is served with a local bean and sausage ‘soup’ [Ed.--fagioli all'uccelletto, a traditional Tuscan bean stew]. Then they taught us a version made with chestnut flour [Ed.--necci] and rolled around fresh ricotta. After this, we went to another village to learn the same technique for one with no yeast or rise, a mix of flour and cornmeal [Ed.--criscioletta of Cascio], with strips of pancetta cooked into it. Needless to say no one was hungry for dinner. A flour mill that is still driven by water. Note that the water wheels are horizontal. They made the flours for our flatbread class. Then on to more beautiful places. Rhonda was unable to take part in the final day of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany. If she had she would have learned about the Slow Food Presidium Garfagnana potato bread with Paolo Magazzini. With a visit to Paolo's farro polishing machine and free range beef cattle during gaps in bread making. Topped off with a lunch cooked by Paolo's wife!

This was all part of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany, which will be taking place again from 11–16 February. It used to be in July, but it's too hot now to do anything, much less bake bread. Find out more here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here.

0 Comments

Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

‘Relax!’ is a command to me as a tour organiser and to you as a traveller. There’s no way you can see everything, so we may as well leave time to rest, absorb and enjoy. My favourite way to wind down is to go to a village festival, called a sagra. It’s impossible not to relax, while at the same time soaking in the local culture.

The village of Cascio is top of my list for an experience without deadlines. I’ve already written about its wood-fired oven sagra in spring (http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/a-feast-from-wood-fired-ovens/). At the end of July and early August the village puts on its equally relaxing Sagra delle Crisciolette. See below for a note about the criscioletta. Right now, we’re going to the sagra. Just click here to take you to the Slow Travel Tours website for your anti-stress therapy (and to find out what a criscioletta is): http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/relax/ The Garfagnana is unquestionably beautiful. It’s rugged mountains cloaked with green forests set it apart from the Tuscany of Chianti to the south and the Po Plain of Emilia over the Apennine Mountains to the east. But I could never understand what use it could possibly have been to the Dukes of Ferrara, the Este family. In 1429 Nicolò d’Este annexed the Garfagnana to his realm and for almost four centuries the Garfagnana remained under the Dukes, who defended it against the republics of Lucca and Florence. I searched the internet; I asked my city guide in Ferrara. It seemed never to have occurred to anyone to wonder why. Today I went to the Sagra della Minestrella di Gallicano. Minestrella is a soup of wild herbs and beans made only in Gallicano, a town of fewer than 4,000 people. Today it is the southernmost town in the Garfagnana. When the Garfagnana was under the rule of the Dukes of Este, Gallicano was the northernmost Lucchese stronghold (apart from the even smaller town of Castiglione di Garfagnana). Directly across the river in Barga the Florentines held sway. Surrounded by strong neighbours, Gallicano went its own culinary way. The plan of the day included an introduction to wild edible herbs, a walk (in the rain — not planned) identifying the edible herbs along the path to the Antica Trattoria dell’Eremita (Old Restaurant of the Hermitage), where we not only feasted on the legendary minestrella, but numerous other traditional dishes illustrating the use of wild herbs, not omitting the focaccia leva, a flatbread unique to Gallicano. The conversation turned time and again to the detailed history of the region and the extent to which it influenced agriculture and culinary tradition. Everyone seemed to be well versed in the history of the place. It was the symbolic and often the actual basis of their ownership of the land. I talked to Cesare, who had organised the event, about taking my clients to forage for edible herbs and use them to prepare a meal. He was agreeable, but cautioned that the activity wasn’t to be just about the identification of the plants, their recipes and flavours; it had to include their cultural history, what they meant to the families who ate them. Ivo Poli, who had given the lecture on the wild plants, gave me a lift back to my car. He lives in the next town north of Gallicano and had always been a Garfagnino (citizen of the Garfagnana). I asked him the question that had teased me for so long. It’s easy, he said, ‘We had the petroleum of the Renaissance: charcoal.’ I’d walked in the tree-covered mountains; I’d seen a charcoal burner at work; I’d watched the blacksmith Carlo Galgani beating iron in his charcoal fire; I’d been to a village that produced nothing but nails; but I’d lacked the historical glue to put them together. Far more important than nails and horseshoes, every ruler needed charcoal to smelt iron to make arms to defend his borders and subdue new territories. The village streets lined with grand houses with imposing doorways suddenly make sense as residences of the oil barons of their day.

Yesterday I took three generations of women to Vitalina’s dairy to learn to make ricotta and then to Beatrice Salvi’s hotel for a lesson in baking a traditional Garfagnana ricotta pie. You can’t make ricotta unless you make cheese first, so the added bonus was they learned to make goat’s milk cheese too. Before we arrived Vitalina had spent 2 hours milking 70 of her goats. She heated 60 litres of unpasteurised milk to blood temperature and added rennet. By the time we arrived, the milk proteins had coagulated to a gel and were ready for Liz, one of the guests of Sapori e Saperi, to have a go at cutting it to separate the curds and whey. Vitalina showed Maggie and Abby how to gather the curd which turned out to be harder than they thought, but they had fun feeling around for the curd at the bottom of Vitalina’s grandfather’s tinned copper pot. Vitalina learned from her grandfather and father and makes goat’s milk cheese and ricotta twice a day. After a little experience it’s really very easy. Notice that the curd is white but the liquid in the pan is yellow. That’s the colour of whey. Now the ricotta lesson begins. Vitalina turns the burner on high to start ‘recooking’ the whey. Ricotta means recooked and it can only be made from the whey. That’s why you have to get all the cheese curds out before you can make it. And by the way, almost all the fat comes out with the curds. While the whey is heating up, Maggie helps Vitalina press the remaining whey out of the cheese and Vitalina adds the whey to the pot. When the whey gets near boiling, the albumin protein molecules in the whey denature, which means they open up to expose their connection points so they can attach to other molecules to form white strands, just like when you boil an egg and the previously clear egg white turns to solid white. The white strands are ricotta. Luckily they float so you don’t have to plunge your arms into boiling whey. You just skim them off the top and layer them gently in the ricotta mould. Vitalina gives us some warm ricotta to taste. Everyone exclaims in unison: ‘Delicious! It’s nothing like the ricotta we buy in the States. This is so much better.’ Since ricotta is virtually fat free, they’re also bewildered as to why in the States there are two types of ricotta: full fat and fat free. I’m bewildered too and cynically guess it’s a marketing ploy. If anyone knows the answer, please leave a comment. Clutching our precious ricotta we go to lunch at L’Altana, my favourite restaurant in Barga. The cooking is excellent, but what I love about it is that the staff are equally good. One of our group is coeliac, and as soon as I tell our waitress, she goes off and comes back with a menu on which the items without gluten are marked. Since the menu changes daily, she’s done it specially for us. Then we walk to Villa Moorings Hotel where the owner, Beatrice Salvi, teaches us to use our ricotta in the traditional Garfagnana torta squisita, which means ‘very delicious pie’. First we make pasta frolla, a sweet pastry made of flour, egg, sugar, baking powder and melted butter. It’s the basis of most pastry in our area. The eggs come from Beatrice’s father’s farm. The yolks are deep orange, nearly red, and the whites are yellow and thick. The filling is made of ricotta, eggs, sugar, chocolate chips and a little Sassolino, an anise-flavoured liqueur. Goat ricotta is ideal for filling ravioli, but Beatrice and I were worried that it would be too strong for the pie, and Beatrice had bought some industrial cow ricotta just in case. Everyone tasted both of them except Beatrice. She said she didn’t like ricotta! I’m afraid I’m a bit of a bully when it comes to tasting, and finally she took a tiny spoonful of our goat ricotta. I wish I’d got a photo of the smile on her face. The industrial ricotta was a tasteless paste by comparison. We used our artisan ricotta, and the torta squisita, topped with a thin meringue, was truly delicious.

When I went to dinner with some friends, I took them some formentini, biscuits I had baked. I also gave a few to the other couple who was there. After a delicious dinner followed by an elaborate meringue pudding, I departed feeling extremely well fed and as if I might not be able to eat for a week. A few days later I received a surprising email from the other couple telling me they had loved the cookies, had eaten them all before they arrived home (only a 10-minute drive away!) and asking for the recipe. Here it is.

Formentini (cornmeal cookies) The name comes from the word formenton which means maize or corn in the Garfagnana dialect. The recipe is from a wonderful little book of traditional recipes of the Lucca region, Cucina di Lucchesia e Versilia, by Emiliana Lucchesi. Quantity: masses (I make half a recipe) 600 g plain white flour 400 g corn meal 400 g sugar 225 g butter, gently melted 2 eggs 1 packet baking powder (16 g) juice and grated rind of 1 orange milk Sieve together the two types of flour and the baking powder and pour them onto a pastry board (spianatoia) in a mound. Make a hole in the centre and add the other ingredients. Knead everything well with your hands, adding enough milk to obtain a soft compact dough. Roll out with a rolling pin to a sheet about 3 mm thick. Before making the last pass with the rolling pin, sprinkle the dough with a little sugar and roll it into the surface of the dough. Cut into diamonds or rectangles (about 4 cm on a side), place on a buttered and floured baking sheet and place in a 220˚C oven for 10–15 minutes. They are done when they are just beginning to brown around the edges. Remove from the baking sheet immediately and leave to cool on a wire rack. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed