|

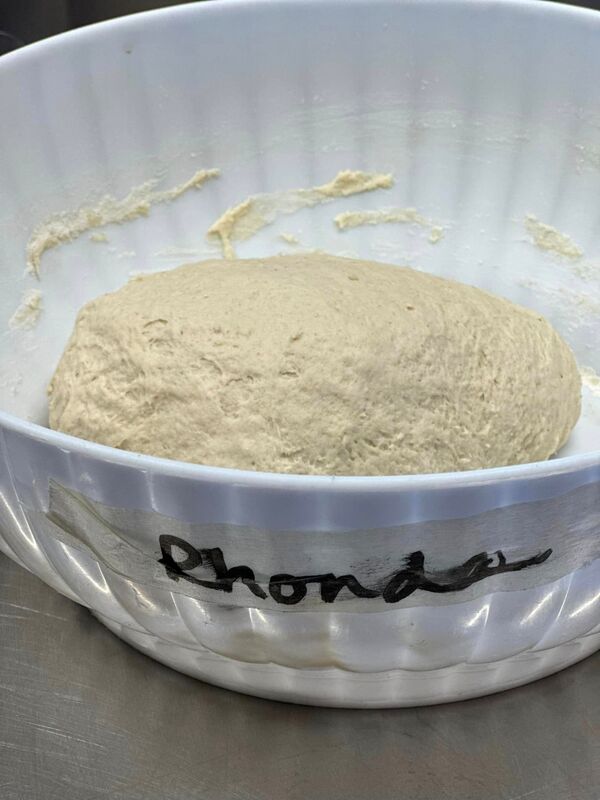

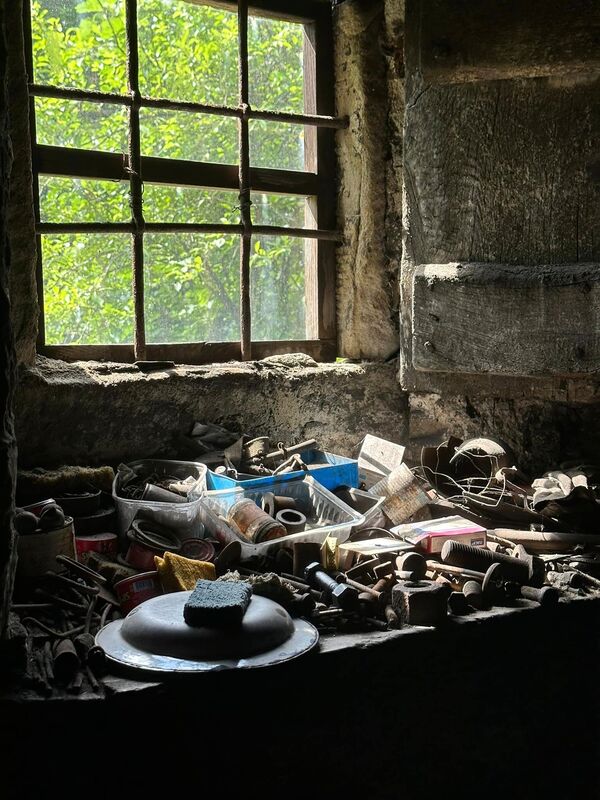

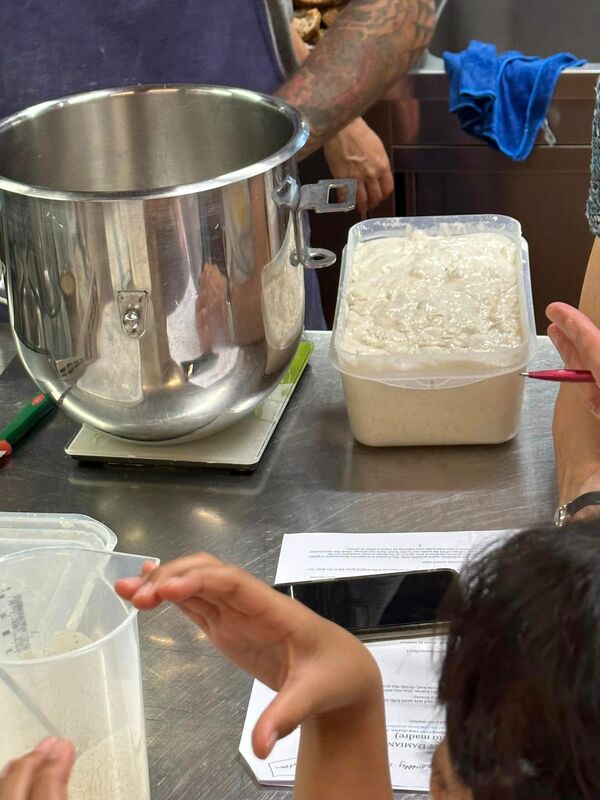

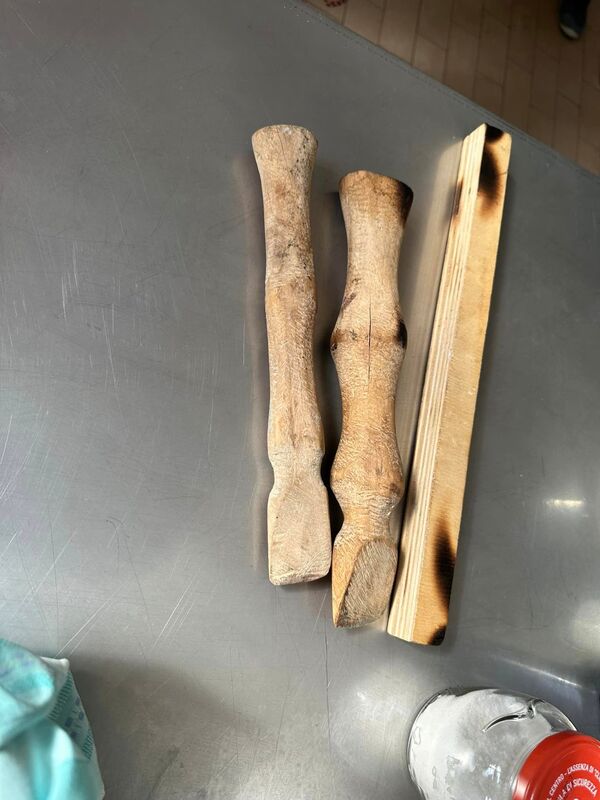

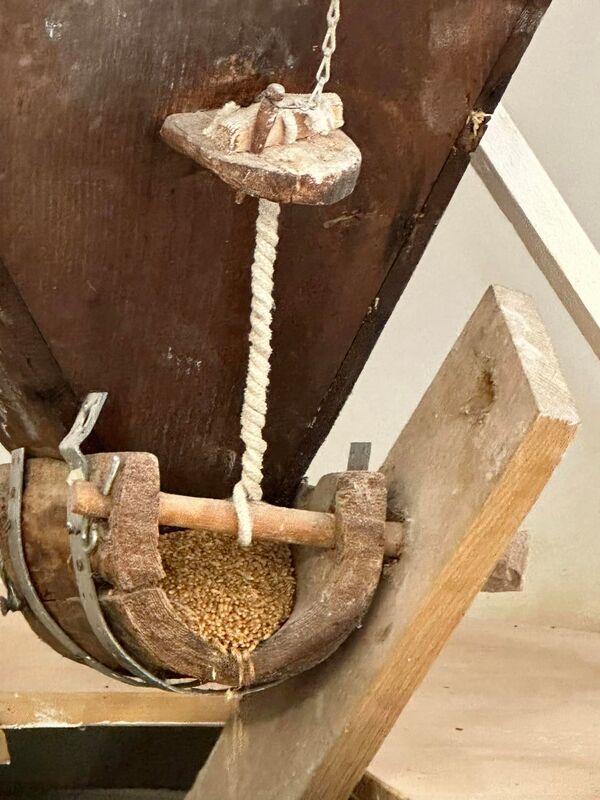

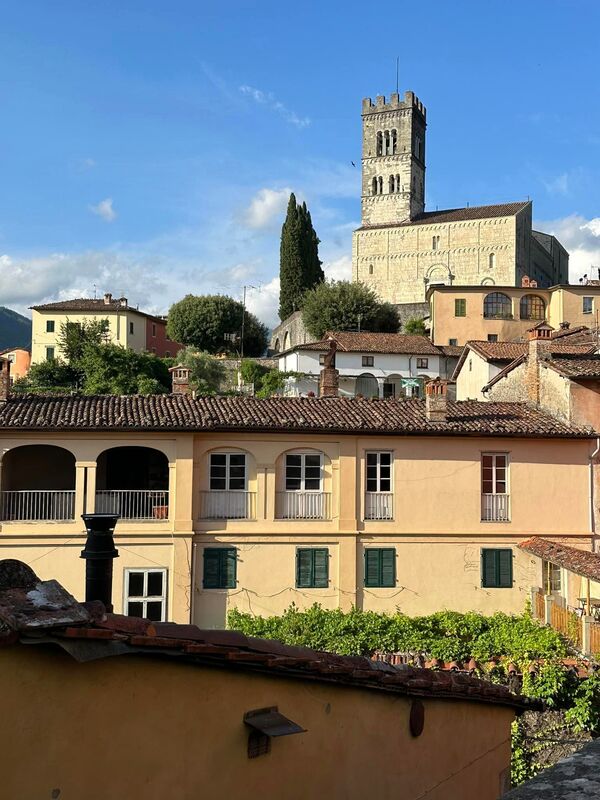

Rhonda Gothberg, a goat farmer and cheesemaker from Washington State, USA, joined us on the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany this year. She shared wonderful commentary and photos online during the course and has allowed us to share them with you in this blog post. We have put together her comments and photo captions below. Enjoy! First a note from us: Rhonda had travelled around Italy before joining the course, which began in Hotel Park Regina, Bagni di Lucca.  Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Sourdough bread making today with Chef Damiano at Fattoria Sardi. We were also treated to lunch there. We go back tomorrow to bake the bread and another lunch. Oh my goodness...all around excellent. A highlight today is a visit with Carlo. He’s 85 years old. His family has been blacksmithing for over 500 years. Sadly, no one is coming up behind him. This place is fascinating! It is run completely on water power. Such a skilled master artisan. We were all mesmerized. Today we worked with Chef Damiano again and got our bread baked from yesterday. We then had a tour of Fattoria Sardi vineyards and wine areas. We learned to make our own sourdough starter. Then another fabulous lunch. After that we visited a farmer who grows ancient varieties of wheat. A brief rest at the hotel then out to dinner for pizza and a beer. We learned to make these yeasted flat breads [Ed.--fogaccia leva di Gallicano] yesterday. These are made on traditional flat iron sort of griddles. Some call the pan testi but there are other names [Ed.--cotte in Gallicano] depending on the village tradition. Our hosts have been best friends since birth. What a duo! The ensuing lunch with this traditional food was really good. It is served with a local bean and sausage ‘soup’ [Ed.--fagioli all'uccelletto, a traditional Tuscan bean stew]. Then they taught us a version made with chestnut flour [Ed.--necci] and rolled around fresh ricotta. After this, we went to another village to learn the same technique for one with no yeast or rise, a mix of flour and cornmeal [Ed.--criscioletta of Cascio], with strips of pancetta cooked into it. Needless to say no one was hungry for dinner. A flour mill that is still driven by water. Note that the water wheels are horizontal. They made the flours for our flatbread class. Then on to more beautiful places. Rhonda was unable to take part in the final day of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany. If she had she would have learned about the Slow Food Presidium Garfagnana potato bread with Paolo Magazzini. With a visit to Paolo's farro polishing machine and free range beef cattle during gaps in bread making. Topped off with a lunch cooked by Paolo's wife!

This was all part of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany, which will be taking place again from 11–16 February. It used to be in July, but it's too hot now to do anything, much less bake bread. Find out more here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here.

0 Comments

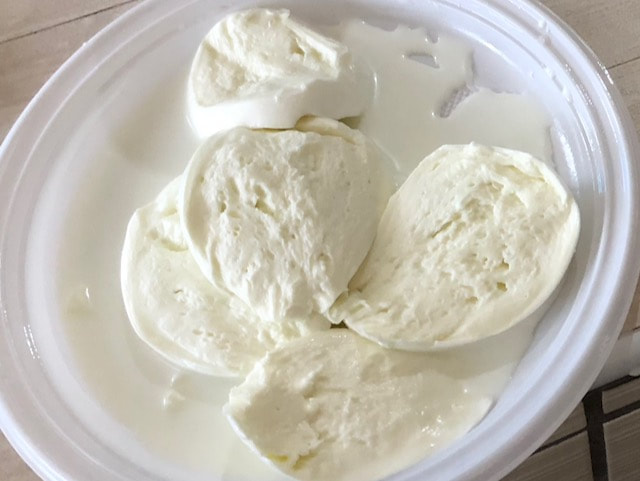

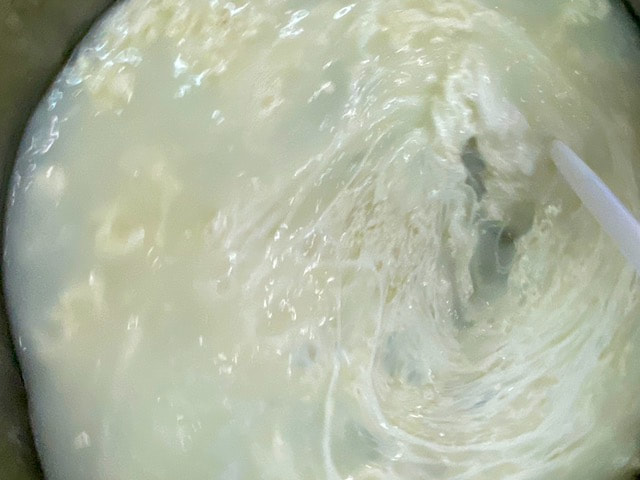

Guest blog by Adam S. Thompson, Head Cheesemaker & Partner at OroBianco Italian Creamery (Texas, USA) I've waited a long time to learn the art of pasta filata. After 15 years of making "mozzarella" or something in that genre, I can finally say I actually know how to make traditional pasta filata cheeses, using water buffalo milk, as it was intended to be produced. My name is Adam S. Thompson, and I'm the head cheesemaker and partner at OroBianco Italian Creamery — the one and only water buffalo dairy and creamery in Texas. I've been making cheese for over 15 years, with my first one being a quick method mozzarella, using citric acid and store bought milk. Before the buffalo, I had a goat dairy and made an array of cheeses and yogurts from their milk. I've also made sheep and cow milk cheeses at a couple of other operations, and trained in Mexico City on Oaxaca cheese — a pasta filata cheese, but made in a completely different fashion. I joined the team at OroBianco in September of 2021, however, I had been doing some testing of the milk as early as March of 2021. For the past year, I've made a couple of decent products that somewhat resemble mozzarella, but never could get the texture and flavor of what we really wanted — an authentic buffalo mozzarella, that oozes the milky water out when you bite into it. Made and served fresh and meant to be eaten almost immediately. While Covid restrictions were preventing me from taking this course, Erica Jarman of Sapori & Saperi helped me as much as possible from afar, even getting a Zoom class going with the former head cheesemaker at Prime Querce farm and dairy. She had also been telling me that I needed to see the process and experience it firsthand to really understand it. I’ve attempted the mozzarella at least 50 times over the last year, sometimes pushing into the morning sunrise, trying to accomplish this cheese making process. Time and time again, I would get a nice cheese, but not the mozzarella we were aiming for. Finally, in October 2022, I arrived in Campania, Italy, to take the course. The class was the most educational course I’ve ever received in such a short amount of time. I think it helped I had been trying and failing, as I had many questions to be answered and walls to get over. Any time I had a question, no matter how small or off-topic to the current stage, Erica would wait for the cheesemaker to finish what he was talking about, and field my questions to him. We trained at two different dairies, Chirico and Prime Querce. Each place had its own methods and variations for the different pasta filata cheeses, but the basics were more or less the same. The cheese making facilities were full of passionate people, who would move like ants at times, in a synchronized, and super-speed fashion at times. I was allowed to make a complete batch at one facility, then work on all of the different stages at another, in the midst of normal production. I had no question left unanswered after this course. The mozzarella and pasta filata training here was incredible, but there was much more to this course. We also had the pleasure of being accompanied by a very talented sommelier, and did nightly wine tasting, and went to dine at some of the finest establishments I’ve ever eaten at. Some were embellished with gold trim and crystals, serving high-grade steaks, and some were little hidden gems, with the morning’s fresh catch served in unique presentations. We even had a “dinner with friends” where one of the B and B owners invited some locals, and we dined family style in the living room. The entire course was very organized and maintained on a sometimes very strict schedule, and this ensured we were always where we needed to be to learn, and visit the extracurricular, planned activities. Everything was purposeful and useful to bring these skills back to Texas and incorporate into my cheesemaking, as well as bringing information about the water buffalo themselves back to the dairy. To anyone wanting to learn the art of pasta filata, this course is a must-take. You won’t call one of these places directly and get a class, and you won’t find these courses online, or marketed on some big cheese website. Most places are very secretive, or do not want to waste the time teaching other people how to make this classic cheese. The food alone is worth the cost of the course, in my opinion. Of course my focus was always on the cheese making, but the course being completely submerged in the culture, and getting to taste different foods, and wines, from around the terroir left me with an elevated sense of inspiration. The people there were very welcoming, and passionate about their trade. Not only have I finally locked down the mysteries of mozzarella, but found myself returning home and making my own tomato sauce, gnocchi, and other classic Italian dishes for my family. If you’re “stretching” mozzarella at home or for a dairy/cheesemaking facility, you’re likely doing it wrong. True mozzarella only takes the perfect curd, and almost boiling water, and it “spins” together almost effortlessly. The mozzarella should make you take a step back when biting, so the beautiful, milky whey doesn't get all over you. So break out the pocket-book, book this course, and get a class that will give you all the tools you need to make mozzarella, as well as fill you with inspiration and the Italian culture that makes this cheese what it is.

By Alison Goldberger When I wanted to learn how to make salami I knew travelling to Italy was the only way to do it, so I booked onto the Advanced Salumi Course in Tuscany with Sapori & Saperi Adventures. The course was incredible, and I learned so much. I was also so impressed by Erica and her company that I asked her if we could collaborate. I’m a Scottish journalist and organic pig farmer but have lived and worked in Austria since 2015. Now I assist Erica with social media and online marketing. I absolutely love telling people about my time on her course and now I am excited to share with you why I think travelling with a local expert in 2022 (and beyond) can only enhance your holiday experience! Eat in incredible restaurants...and in private homes One of the most wonderful experiences I had was to dine in restaurants uncovered by Erica after years of eating and living in Tuscany. You can be guaranteed you’re not just eating in the restaurant all the other tourists found online! We were treated to dinner at Il Vecchio Mulino, where Andrea brought out course after course of exquisite local food. Many of Erica’s courses and tours also include meals in private homes. In Capezzano I was welcomed into Gabriella’s home where I ate the best seafood I’ve ever had. The freshest seafood cooked to perfection and an extremely warm welcome – it was an unforgettable experience. Learn how to make prosciutto as the artisans do Do you have a passion for prosciutto like I do? It’s unlikely you can just stroll up to any producer and they’ll tell you how it’s done. But when you travel with a local you certainly can, and they are happy to answer all your questions. When learning all about salumi in Tuscany I visited numerous artisans and gleaned the knowledge they’ve garnered over a lifetime. On these tours you’re also supporting these very small businesses, creating wonderful slow food with a passion you’re unlikely to find in large-scale producers. What’s more, you get to taste their incredible products! Savour products from small-scale producers You want to visit a local organic olive oil producer, or have always wondered how chestnut flour is produced, or perhaps gelato is more your thing? These were all requests during my course and every one was fulfilled! I took home a bag of chestnut flour after seeing how chestnuts are dried and milled. I sampled the best pistachio gelato at Cremeria Opera in Lucca and bought the tastiest new-season olive oil from Claudio Orsi of Alle Camelie. Erica has built up so many contacts across the region and she is happy to help visitors find what they’re looking for.

Erica drove us during our course so she was always on hand to answer questions and give us explanations about what we were seeing as we travelled. It was information born from a passion for Tuscany and gave us a wonderful insight into the history of the region as well as what it’s really like to live there. This is a feature of all tours and courses from Sapori & Saperi. For instance, on the Tastes & Textiles tours participants learn all about Lucca’s rich tradition of producing textiles. Meeting local craftspeople provides a wealth of knowledge you couldn’t get elsewhere! Did someone mention gelato I know one of my first thoughts when I think of Italy is gelato. We were taken for a quick pit-stop to sample some delicious gelato. It was actually in the Cremeria used for the Art & Science of Gelato course run by Sapori & Saperi. During that course participants immerse themselves in the icy world of Mirko Tognetti of Cremeria Opera Naturali per Gusto, Lucca. They learn his secrets and the science behind gelato and how to create their own flavours. Sounds like an absolute dream to me!

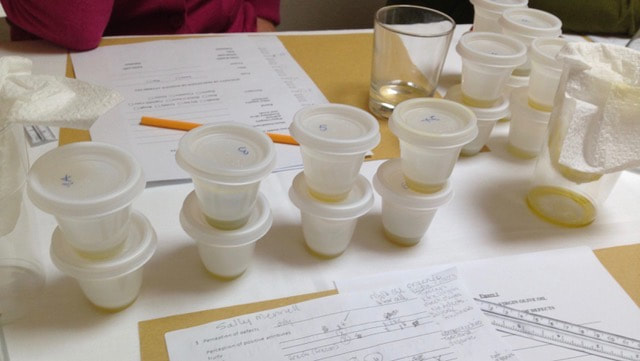

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 20 January, 2019. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 28 January 2017. Did you know that olive oil is the only common cooking oil that is the juice of a fruit? All the other oils we use in our kitchen come from seeds: sunflower, rapeseed (canola), peanut and grapeseed. This realisation leads directly to another question. Would you cut an orange, leave it on the counter for a week and then squeeze and drink the juice? Would you step on an apple, leave it on the table for three days and then eat it? Yet that’s what happens to many olives before they’re pressed to extract olive juice. I’ve tasted and written a lot about olive oil, but this idea had completely escaped me until I met Elisabetta Sebastio last year. She’s a professional olive oil taster both for Italian Chambers of Commerce and international olive oil competitions. We ran our first full-day olive oil class during my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November 2016 (now we run a full course on the subject of olive oil: Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany). It was a revelation for all of us. We gathered around her kitchen table. She taught us how the professionals taste and rate oil. We tasted eight olive oils. The first was a surprise and I don’t want to ruin the impact by telling you what it was. Then there were four new-season oils: one from Sicily, two from Tuscany and one from the Abruzzo. Some people liked the tomato scent of the Sicilian one, others the bitter piquancy of the Tuscans. Lots preferred the less in-your-face qualities of the Abruzzese. Under Elisabetta’s guidance it was so easy and we were proudly feeling like experts when we started on the three defective oils. Wow! It was so clear that they didn’t measure up, and we could describe what was wrong with them: rancid, vinegary and fusty. We didn’t want to put them in our mouths. You’ll taste lots of mildly rancid oils in restaurants due to poor storage in clear bottles in the warmth. There were more revelations. Contrary to popular belief, true extra-virgin olive oil has the highest smoke point of any vegetable cooking oil. Another fact some people don’t realise is that it deteriorates with every passing day, even in a sealed bottle. If you’ve got some excellent oil, carpe diem. It will be worse tomorrow. But olive juice isn’t just for cooking. In Italy it’s mainly used as a condiment, like salt and pepper. This got us thinking about which olive oil goes best with which foods. Elisabetta had devised a lunch to demonstrate the classic pairing of regional dishes with an oil of the same region. We got to help prepare orecchiette (an ear-shaped pasta from Puglia) with an artichoke sauce seasoned with extra-virgin olive oil from Puglia. Sadly, we ran out of space in our stomachs before we could taste all the different dishes Elisabetta had prepared. I took another group to her home in December. One of them loved chocolate and Elisabetta assured me she could source some olive-oil flavoured chocolate. The platter of chocolates was beguiling and they tasted fantastic. She had made them herself! Join me on the course Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany from 18–23 November 2021 and meet the amazing Elisabetta and have fun with olive juice.

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This article originally appeared on Slow Travel Tours here. There’s a baby in the house. It’s my new-born olive oil course this autumn, on which you’ll find out how to get the maximum enjoyment from olive oil. Do you have any idea how exciting it is to visit an olive mill to see and smell the new olive oil pouring out? And what about the flavour? If you haven’t been in Tuscany in the autumn, you will have a hard time imagining how intense and delicious it is. Then there’s the food for your eyes: those old silver-haired beings rooted on terraces retained by dry-stone walling. Who will have fun learning about olive oil? Many educators focus on a particular group of people: chefs, gourmets, home cooks, dieticians, olive cultivators, olive oil vendors. They reason that each group wants to know different things, that their curiosity is confined to their own particular box. I have a different methodology and more faith in the innate curiosity of people. I always design my courses for the person I was when I first arrived in Lucca. When it comes to olive oil, I knew nothing except that some dishes should be cooked with it. I used a supermarket brand of extra-virgin olive oil, not the cheapest and not the most expensive. I didn’t know what I wanted to know. I didn’t even know what questions to ask. In my fifteen years in Tuscany, a whole universe of olive oil has opened up before me and yet there’s always more to discover. Just this week I visited Pietro Barachini, a propagator of olive trees. I saw the forest of tiny cuttings which would be ready for sale only after two years. Then it takes ten years or more for the tree to be in full production. Producing olive oil is not instant gratification! What about tasting the oil? What is that medium-priced supermarket extra-virgin olive oil missing (is it even really extra virgin)? What defects can you taste in it? Every day you have guided tastings. You won’t become an oil judge overnight, but you’ll discover a brand new palette of flavours from the fruity tomato-leaf scented Sicilian oils to our spicy, bitter Tuscan oils. Your mind will be racing with ideas for using different oils with different ingredients. Your lessons making gelato and chocolate with olive oil will stimulate your creativity. We also want you to know about the health-giving aspects of olive oil. They make a significant contribution to the Mediterranean diet and are another good reason to consume high quality oil. You’ll also get answers to your practical questions, like how to find good olive oil in your own country, what the writing on the label means and how to store the oil to slow down its deterioration until next year’s new oil is available. If you want to learn in five thrilling days what it has taken me fifteen years to find out, come on the Olive Oil: Tree to Table course this autumn. It’s taught by Elisabetta Sebastio, a professional olive oil taster and judge, sitting on panels that decide which oils will get the highly sought-after DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) each year, along with several other experts who want to pass on their knowledge at whatever level you’re at from beginner to experienced professional. By the end you could be jumping up and down with excitement at having the tools and confidence to make your own choice of which olive oil to buy and how to use it in your home or your restaurant’s kitchen. If you sell olive oil, you’ll be able more intelligently to advise your customers. If you’re a producer, you’ll have the opportunity to talk with experts. The culture of olive oil will be in your blood.

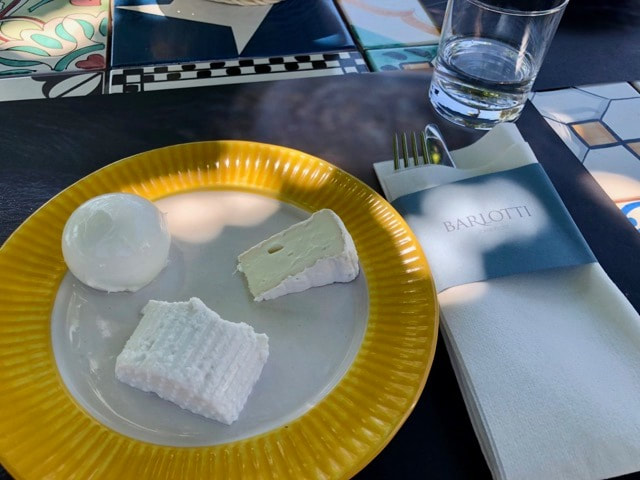

If you have an open mind and an insatiable curiosity, ask for a booking form now: [email protected] If you’d like to read more about olive oil, here are some of my other blogs: Olive Juice, No Olive Oil, Olive Oil is Fast Food This blog post is part 2 of my recent travels around Italy. You can read the first part 'Food & Wine in Napoli & Pompei' here. But for now, let's start with the second half of my tour... I take the train from Pompei to Salerno and change for the regional train heading south. Maria Sarnataro picks me up at the station at Vallo di Lucania. We arrive at her home just in time for dinner. She has a surprise for me, a manteca. It’s butter encased in caciocavallo cheese and it has a story. The people of Basilicata who take their Podolica breed of cattle to alpine pastures for the summer make caciocavallo which they mature until they descend to the valleys in autumn where they sell it. They make ricotta from the whey, but there’s too much for them to consume fresh. It can’t be kept for more than a few days and there's nowhere to sell it. So, by an ingenious and complex process of draining, heating and cooling, they extract the butterfat from the ricotta. To conserve the butter without refrigeration they encase it in a thin layer of caciocavallo curd. Piero, Maria’s husband, is an agronomist. Part payment for his consultancy with these people was this manteca. There are so many mozzarella dairies in Salerno Province that you could spend several weeks visiting all of them. There are two that I’ve heard excellent reports of and haven’t managed to visit: Barlotti and Vannulo. Vannulo is organic, only sells from their own shop at the dairy and often comes at the top on lists of the 10 best mozzarellas. Maria has booked lunch there. On the way we stop at Barlotti where she introduces me to brothers Enzo and Gaetano Barlotti. We eagerly accept Enzo’s invitation to bring the participants on our mozzarella courses for a tasting. You taste so much bad mozzarella everywhere else that we need to educate our palates while here. He presents us with samples of his bocconcini, ricotta and a new brie-style cheese, all made with the milk of their own buffalo herd. The mozzarella and ricotta are among the best I’ve tasted. The ‘brie’ is a little bitter and needs some work, but it’s exciting that they’re experimenting with new cheeses. Many of the mozzarella dairies offer tastings in beautiful settings and some have a dining room where you can sit down to a multi-course lunch. Vannulo has perfected the tourist experience, which as you probably know by now, puts me right off. Maria is a friend of the owners, but they don’t welcome us when we arrive, and are nowhere to be seen. Maria tells me that it used to be different, but now it’s all hired staff, who display not an ounce (not even a gram) of passion for their products. Our vegetable salad from their organic garden is good, the mozzarella not outstanding. They’ve installed a leather workshop which sells their own handbags, etc, but they take no interest in us visitors. The museum of agricultural implements is marginally interesting, but I’ve been to better ones. If you come on the mozzarella course, you won’t be visiting Vannulo on our tasting afternoon. Francesca Fiasco’s vineyard at Felitto couldn’t be further from a tourist experience. The only sign on the road is Francesca herself waiting to show Maria and me her vineyards and cantina (cellar). She exudes passion and authenticity and does virtually all the work herself right down to designing the labels. She cultivates autochthonous varieties such as fiano, aglianico and piedirosso (the one I saw at Pompei) as well as varieties such as sangiovese and merlot, which arrived in the area so long ago that they are included in the DOC. She produced her first wine in 2016 and is already being recognised by wine critics. She gave me a case of wine with a handwritten label. Sadly, I couldn’t carry it back to Lucca on the train. I know Maria will make good use of it. She not only teaches cheese courses, but also sommelier courses. Just so you know my trip isn’t all hard work eating and drinking, this morning Maria takes me to her favourite secluded beach, fairly free of tourists (especially in these times of Covid-19). You have to go a long way to find gelato as good as Mirko Tognetti's of the Cremeria Opera at Lucca. Here I am at Sapri in southern Campania enjoying Enzo Crivella’s latest creation which he’s describing animatedly. They sound an unlikely combination, but it works. Try it! You have to make a perfectly balanced bread gelato. Maybe best to come on Mirko’s and my gelato course first! 😃

That marks the end of my tour. I'd love to welcome you onto one of our tours or courses soon. Take a look at our website to find out dates and details and get in touch with me to book your spot. I look forward to seeing you! By Alison Goldberger In February we took off from our base in Tuscany to head to Emilia (the northwestern part of Emilia-Romagna). This region of Italy is particularly famous for not one, but two delicious types of salumi— Prosciutto di Parma and Mortadella di Bologna! This is why a group of eager students joined us to learn how to make these incredible products for themselves on our Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma. During our induction we dove right into WHY we learn here and discussed artisanal production vs la Grande Industria. We met passionate farmers Giorgio & Claudia Bonacini at their farm, Il Grifo, near Reggio-Emilia. They are the definition of artisanal production. As we toured the farm where they rear Mora Romagnola pigs we heard about how they keep the whole production cycle at home and how they farm their 65 hectares biodynamically. They showed us the Modena cut, how they make salami, mortadella and the method for salting whole pieces. We also had the chance to inject a coscia (leg) with flavoured brine to make prosciutto cotto, but we didn’t have time to cook it. We think it would have tasted absolutely wonderful though! As soon as you ask Giorgio a question, he grabs a pen and sheet of paper and starts illustrating what he's talking about. We sometimes joke that we'll mount an art exhibition of his drawings! One of the parts of the course the students found really interesting was sitting around a table with him and learning how fermentation works. Giorgio loves the science behind curing and fermenting and this passion really rubbed off on our students! We also visited the Brianti family where Aldo and his son Luca rear free-range Nero di Parma pigs and Piemontese cattle on their organic farm. The guys gave us a run-down on a range of salumi typical of Parma—with a break to enjoy Sunday lunch with the family! Here’s a special piece of salumi by the Brianti’s, Fiocco di Santa Lucia. The photo on the front is Luca’s youngest daughter Marika. The fiocco is usually made from one of the leg muscles, but the Brianti’s have started curing one of the shoulder muscles, which they are also calling fiocco. It means ‘ribbon’, so a muscle that is longer than it is wide! Classic prosciutto di Parma was taught by Maurizio Cavalli. He and his family cure and age the Brianti’s prosciutto. In addition to prosciutto, they also produce coppa, culatello, culaccio and fiocchetto. It’s not all about salumi on the course though. We love to give our guests a real taste of the particular parts of Italy we visit. So we also paid a visit to Acetaia del Cristo where we learned all about the production of aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena DOP. Yes, it requires all those words to distinguish the true balsamic vinegar, which takes 12 years to be ready to bottle, from the aceto balsamico IGP, which takes only three months. We tasted it too of course—and discovered for ourselves the huge differences between the two!

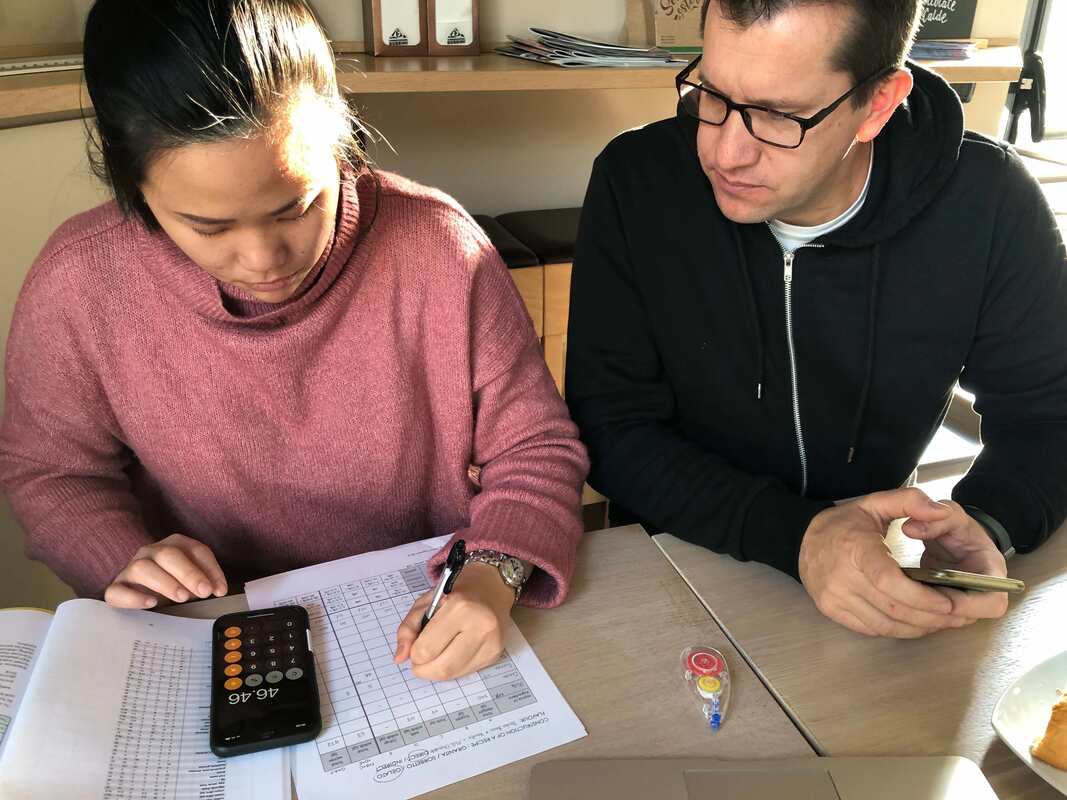

Phew! If this has whetted your interest, take a look at our website for more information. And sign up to our newsletter to be the first to know the dates for 2021! By Alison Goldberger Every month there’s something happening at Sapori & Saperi – lots of interesting people visit and we take lots of photos of our tours and courses. We thought it was about time we shared some with you on a regular basis. Here’s our January round up, giving you an extra insight into the tours and courses with Italian artisans you could attend with us, as well as some snippets of life in Italy! As the new year rang in Erica feasted on a New Year’s Eve meal, typical for the region she lives in. She ate cotechino with lentils. As they’re round, they symbolise money and will make you rich. We’re still waiting! Maybe next year. The good news is that you can learn how to make cotechino during the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany! During the first course of the year we welcomed the talented Sorravee ‘Gin’ Pratanavanich — find her on instagram. As a qualified pastry chef from the Culinary Arts Academy in Switzerland, she wanted to learn how to make delicious natural gelato — so naturally Sapori & Saperi and our artisan Mirko were there to help her. Gin learned the true science of gelato too – and that’s not easy! How to balance the fat, sugar, milk solids and water to make sure the product not only tastes incredible but has the perfect texture too. Friday on the Art & Science of Gelato course is always ‘crazy flavours day’, and Gin really went for it with her recipes. She created the incredible ‘Coffee B’ gelato made from coffee, caramelised walnuts and Baileys! She also took some inspiration from the Thai street food ‘garlic and pepper chicken’ and used soya, black pepper and crispy garlic in her gelato. A brave experiment. She learned it’s valuable to let your imagination run wild — whether you create something delicious, or you learn what doesn’t quite work! We had an unusual first day on the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany as Mirko joined in to learn how to make salami and sausage with our artisan norcino Massimo Bacci. Will Massimo learn how to make gelato next? We had a great group taking part in the course – here you can see them intensely watching artisan norcino Ismaele Turri as he prepares Tuscan prosciutto. Check out our student, former chef to the Ambassador at the British Embassy Prague and now head of charcuterie at Amaso, Vojtech Kalasek, who posted lots of great images on instagram throughout the whole course. During our tours and courses we like to slip in some surprise extra visits. This time we visited Pastificio Martelli which makes pasta in the Renaissance hilltop town of Lari, where our prosciutto specialist Simone Ceccotti has his butcher shop. We left wondering how many machines you can use and still be artisan. We decided that one important thing is that it's natural: only Italian durum wheat and water and dried very slowly for 50 hours. And just as important, that it tastes good and the slightly rough surface holds the sauce.

January also brought us a wonderful guest blog post from Lin Hobley, a weaver-artist and past participant on the Tastes & Textiles Woad & Wool tour. We published a review of the year, and Erica gave a run down of our different hotels and accommodation on Slow Travel Tours. If you’d like to join us, check out our website. Can’t wait to see you! Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

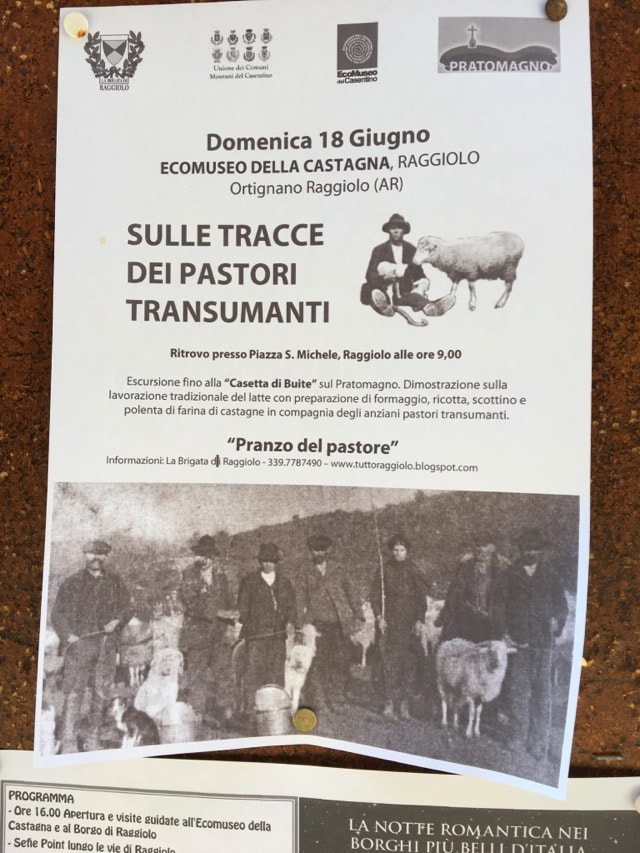

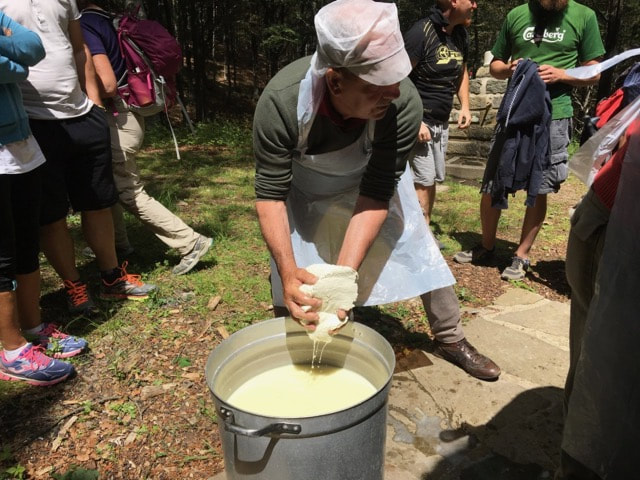

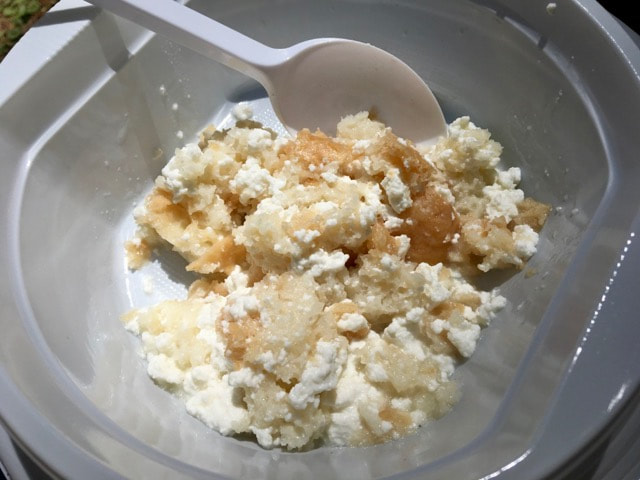

This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed