|

Last night after dinner I went for a walk. The dirt track from Ai Frati, the restored monastery where we’re staying on my ‘Cheese, Bread & Honey’ tour, leads through chestnut woods. It was 9.30 pm and nearly dark. The black tree trunks were wreathed in clouds of fireflies, so dense that they produced a continuous display of tiny pinpricks of light. I stood transfixed. Then I thought of sharing it, but my iPhone 4S was blind to the beauty around it. I can still see the miniature fireworks in my head. I’m glad there are things that ordinary technology can’t deliver and you need to experience in the flesh.

0 Comments

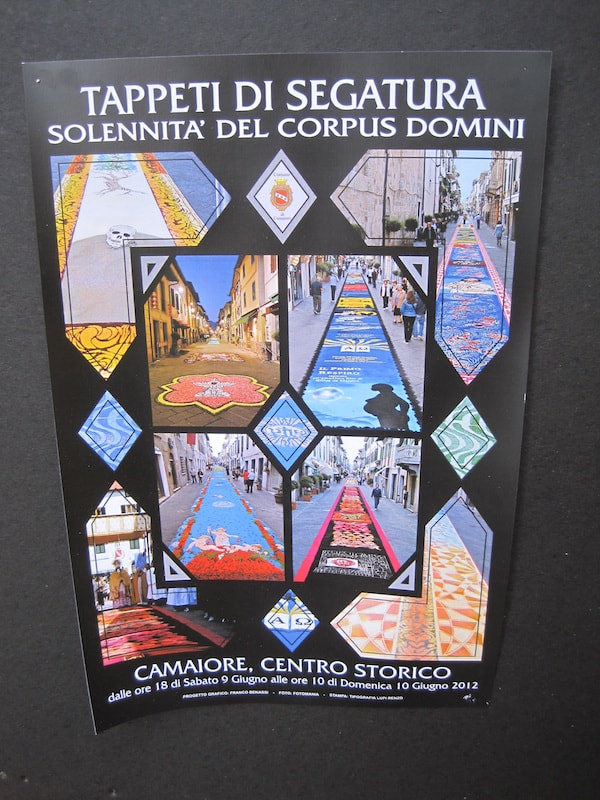

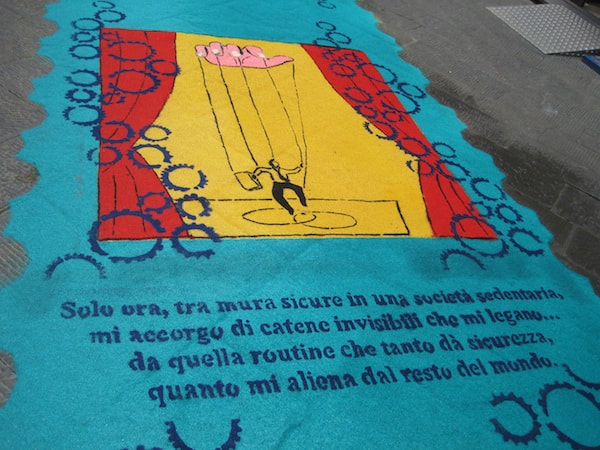

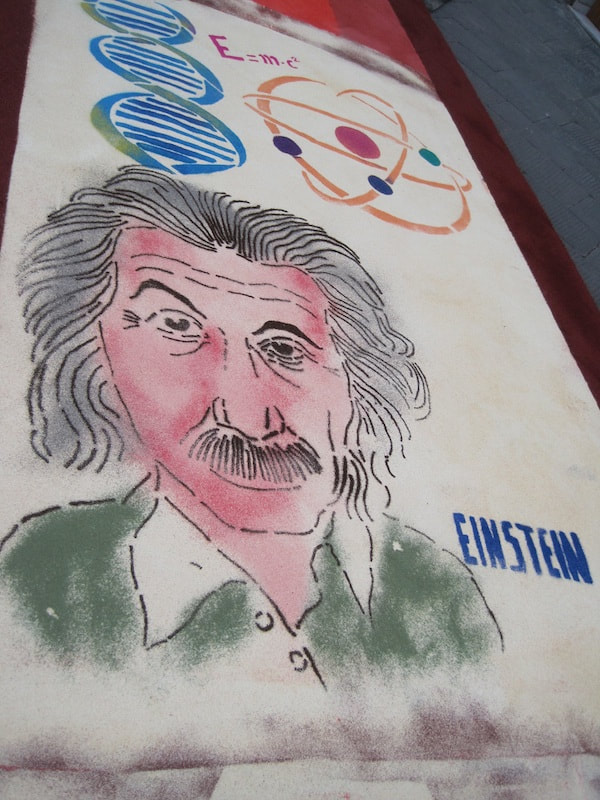

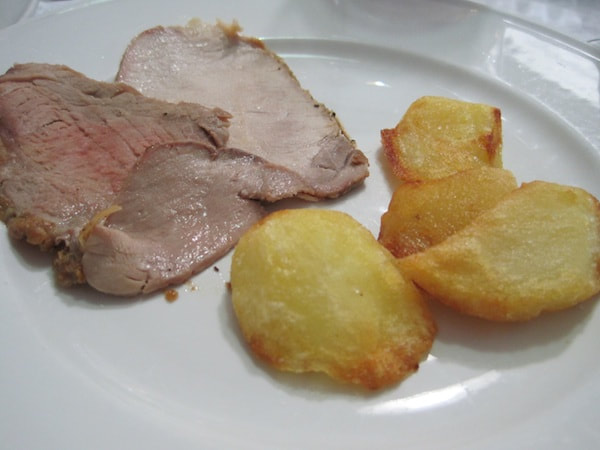

This sounds like a question you type into Google, but it’s what my clients ask me when I’ve taken them to a cheese maker on a mountain top or a handloom weaver in an unmarked house in a higgledy-piggledy mediaeval hamlet or a village festival that’s only announced by the huge number of cars parked along the road when you arrive. I don’t ask Google. In fact, Google usually hasn’t even heard of the people you visit on my tours. The answer is easy, but long. First, I live here (Google doesn’t). Second, I’m blessed with the ‘satiable curtiosity’ of Kipling’s elephant child. Third, I’m not afraid of appearing ignorant or stupid; the only way to learn is to ask lots of questions. Fourth, I go out and research everything that sounds exciting to me. Here’s an example. During the last 24 hours I’ve been to the festival of Tappeti di Segatura Colorata at Camaiore, the Antro del Corchia, Ristorante Vallechiara at Levigliani di Stazzema, Miniere dell’Argento Vivo, tiro della forma sports club and Ristorante Pizzeria Al Barchetto at Turritecava, Gelateria Gely at Fornaci di Barga. It went like this. Saturday 9 June 7.30–8.30 pm: Drive to Gabriella’s house in Capezzano Pianore, near Viareggio and Camaiore. Gabriella is one of my cooking teachers and has invited me to stay the night so she can introduce me to the treasures of Camaiore. 8.45 pm: Dinner with Gabriella, her husband Alfredo, her son and daughter-in-law. 10.00–10.15 pm: Alfredo drives Gabriella and me to Camaiore to watch the teams of carpet (tappeti) designers. Every year on the eve of Corpus Domini (a Catholic religious holiday celebrated on the ninth Sunday after Easter), patterned carpets of dyed sawdust (segatura colorata) are created on the paving stones of the two main streets of Camaiore. The enthusiastic artists work throughout the night so the public can view the finished carpets before 9.30 am when a religious procession walks along the streets and messes them all up. 10.15–11.00 pm: We join the throngs watching the carpet makers of all ages kneeling on the street to sprinkle sawdust in the correct places to build up complex pictures. 11.00–11.15 pm: Drive back to Gabriella’s house. 11:15 pm: To bed. Sunday 10 June 6.45 am: Rise and shine. 7.00–7.15 am: Quick cup of tea (one English habit I haven’t forsaken) and a dry rusk with Gabriella’s homemade wild blueberry jam. 7.15–7.30 am: Gabriella and I drive to Camaiore. Sensible Alfredo is still asleep. 7.30–8.15 am: Wow! 8.15 am: Church bells ring calling the faithful to mass. Uh oh. That means the procession after the mass won’t start until 9.30 or 10. I have too much research to fit in today to stay, and besides that, who wants to see this beautiful handiwork trodden on? We change plans and head to Pasticceria da Rosanno, Gabriella’s favourite, via a few exquisite little churches she tells me all about. 8.25–8.45 am: Coffee and the lightest Italian brioche I’ve ever eaten. 8.45–9.00 am: Start back to car but I’m sidetracked by Gabriella’s casual comment, ‘That’s a good gastronomia’, as we pass Salumeria Nicola. In we go. It’s difficult not to buy some of everything, but I only get a piece of special pecorino called ‘Scoppolato di Pedona’, which I’ll enter in the England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament during my Cheese, Bread & Honey tour the week after this. 9.00–9.15 am: Return to Gabriella’s house and I hastily depart. 9.15–10.00 am: Drive to Antro del Corchia, a cave I’m vetting for a family for whom I’ve designed a tour in July. In my haste to make the 10.00 shuttle bus, I drive right past the turning to Levigliani and have to go back. That’s one reason why I do these reccies. No time to buy a ticket, but I’m waved onto the bus anyway. 10.15–12.15 am: I’m no cave expert but the woman next to me is, and she’s impressed by the three underground lakes, a column that looks like a Golden Eagle plus a ‘petrified forest’ and ‘organ pipes’, and I’m relieved to hear that extensive tests have proved our breathing is but a drop in the ocean in such an enormous cave, the largest in Italy. No photos allowed in the cave. 12.15 pm: I was intending to go straight to the Miniere dell’Argento (silver mines), but naturally they’re closed for lunch. There’s nothing to do but take the guide’s advice and have lunch myself at the Ristorante Vallechiara at the other end of Levigliani. I phone Katherine, my communications manager, and tell her I’ll be late for the tiro della forma (cheese throwing) in the afternoon. 12.30–1.45 pm: I arrive at Vallechiara without a reservation. No worries. Mamma welcomes me into a pleasantly buzzing dining room where her son lays a table for me right in front of the speakers and mixing deck. I ask whether they can be turned down. No, but he lifts up my table and sets it behind the speakers, where the sound is muffled. A plate of pasta fritta (irresistible deep-fried bread dough), wine and tap water appear instantly (many restaurants make a fuss when I ask for tap water and my friends shrivel with embarrassment). The son joins mamma and a waitress carrying around huge trays of antipasto. Bruschetta, four crostini, salumi and melon, olives and a few other delicacies land on my plate before I can order. It turns out Sunday lunch is a fixed menu. No choice, but who can complain about what’s delivered? 1.45–2.15 pm: I have to be at the mine by 2.00, so no time (or room) for the second main course or dessert. I go to the bar for coffee and to pay. After 10 minutes the son arrives and tells me with a grin it’s much harder to pay than to eat in this restaurant. He sends a woman from the kitchen to make my coffee, but she doesn’t accept money. Finally another man arrives and I’m allowed to pay €20 for my delicious lunch that could have fed three. Incredible! 2.15–3.00 pm: Drive to the Miniere. The next tour starts at 3.00, so I sit in the sun. Someone greets me as a group emerges from the mine. It’s Nicolas Bertoux, a sculptor. I haven’t seen him and his sculptor wife Cynthia Sah in a few years. They’ve got more commissions than they can handle, and they’ve restored the studio and have a permanent collection in their private museum. I must come and bring my guests. I will. 3.00–3.30 pm: We don our hard hats and enter the mine. It’s not a silver mine after all. It’s a mercury mine, one of the rare ones where free mercury sits around on rock ledges in little globules. It’s fascinating, but I’m so late for the cheese throwing that I tear myself away before the end of the tour vowing to return. 3.30–4.09 pm: Up over Cipollaio Pass (no one can tell me why it’s named for an onion field or seller), past the disused marble quarry I take my clients to, down past Isola Santa with its houses with stone roofs. I love driving on the curvy mountain roads. Maybe I’ll become a rally driver as my next career. Through Castelnuovo and down the Serchio valley to Turritecava, left at the sign to Pizzeria Il Barchetto (little boat) and down to meet Katherine and her husband Andrea — I suspect I’ll need a man at the cheese-throwing sports club. 4.09–5.30 pm: Tiro della forma, which means ‘cheese throwing’, is a traditional sport of the Garfagnana. In Cheshire, England, there’s an annual cheese rolling competition, but it’s a tame game compared to this pecorino-hurling sport that goes on throughout the year. I’m here to have a look and talk to the owner of the club about bringing guests, especially during the ‘Cheese, Bread & Honey’ tour. We’ll be making our own pecorino, so why not toss it around too? I watch the pros and suspect a cricket bowler would be envious of their technique. See it in slow motion on our Facebook page. Matteo, the owner, is all in favour of Sapori e Saperi guests. Especially if we dine at his pizzeria. On the edge of his fishing lake, we find the cheerful staff clearing up after a wedding party; we check out the wood-fired pizza oven and approve the excellent menu of other typical local dishes. For half a second I contemplate sticking around until 7.00 for pizza, but add it to my future research list and opt instead for an artisan gelato in Fornaci di Barga. 5.30–5.45 pm: Drive to Fornaci di Barga. 5.45–6.15 pm: Behind the counter of Gelateria Gely is a tall, dark, handsome stranger, the owner Paolo Citti. I’ve heard from Debra Kolkka (Bagni di Lucca and Beyond blogger) that he takes his gelato seriously, and I want my clients to benefit from his long experience. I had already tasted his gelato the week before and compared it to three other gelaterias in the area: it’s in a class of its own. At first he’s wary. Maybe I’m a competitor, his recipes are secret, his laboratory is tiny, he’s very busy in the mornings making gelato for his two shops. I tell him about the other artisans I take my guests to and about how important I believe it is for people to learn directly from artisans how much better their food tastes and why. I win him over in the end. We’ll have a go. I can bring up to three people (I bet he wouldn’t turn four away) for a lesson in the afternoon. Who’s going to volunteer? (The news shop across the road is selling parmesan damaged in the earthquakes. Everyone is pitching in to help the producers.)

6.15–6.45 pm: Drive home weary but exhilarated by the results of my research. Everyone I met was kind and welcoming. They were all enthusiastic about helping me and my clients discover the best of Italy. Yesterday I took three generations of women to Vitalina’s dairy to learn to make ricotta and then to Beatrice Salvi’s hotel for a lesson in baking a traditional Garfagnana ricotta pie. You can’t make ricotta unless you make cheese first, so the added bonus was they learned to make goat’s milk cheese too. Before we arrived Vitalina had spent 2 hours milking 70 of her goats. She heated 60 litres of unpasteurised milk to blood temperature and added rennet. By the time we arrived, the milk proteins had coagulated to a gel and were ready for Liz, one of the guests of Sapori e Saperi, to have a go at cutting it to separate the curds and whey. Vitalina showed Maggie and Abby how to gather the curd which turned out to be harder than they thought, but they had fun feeling around for the curd at the bottom of Vitalina’s grandfather’s tinned copper pot. Vitalina learned from her grandfather and father and makes goat’s milk cheese and ricotta twice a day. After a little experience it’s really very easy. Notice that the curd is white but the liquid in the pan is yellow. That’s the colour of whey. Now the ricotta lesson begins. Vitalina turns the burner on high to start ‘recooking’ the whey. Ricotta means recooked and it can only be made from the whey. That’s why you have to get all the cheese curds out before you can make it. And by the way, almost all the fat comes out with the curds. While the whey is heating up, Maggie helps Vitalina press the remaining whey out of the cheese and Vitalina adds the whey to the pot. When the whey gets near boiling, the albumin protein molecules in the whey denature, which means they open up to expose their connection points so they can attach to other molecules to form white strands, just like when you boil an egg and the previously clear egg white turns to solid white. The white strands are ricotta. Luckily they float so you don’t have to plunge your arms into boiling whey. You just skim them off the top and layer them gently in the ricotta mould. Vitalina gives us some warm ricotta to taste. Everyone exclaims in unison: ‘Delicious! It’s nothing like the ricotta we buy in the States. This is so much better.’ Since ricotta is virtually fat free, they’re also bewildered as to why in the States there are two types of ricotta: full fat and fat free. I’m bewildered too and cynically guess it’s a marketing ploy. If anyone knows the answer, please leave a comment. Clutching our precious ricotta we go to lunch at L’Altana, my favourite restaurant in Barga. The cooking is excellent, but what I love about it is that the staff are equally good. One of our group is coeliac, and as soon as I tell our waitress, she goes off and comes back with a menu on which the items without gluten are marked. Since the menu changes daily, she’s done it specially for us. Then we walk to Villa Moorings Hotel where the owner, Beatrice Salvi, teaches us to use our ricotta in the traditional Garfagnana torta squisita, which means ‘very delicious pie’. First we make pasta frolla, a sweet pastry made of flour, egg, sugar, baking powder and melted butter. It’s the basis of most pastry in our area. The eggs come from Beatrice’s father’s farm. The yolks are deep orange, nearly red, and the whites are yellow and thick. The filling is made of ricotta, eggs, sugar, chocolate chips and a little Sassolino, an anise-flavoured liqueur. Goat ricotta is ideal for filling ravioli, but Beatrice and I were worried that it would be too strong for the pie, and Beatrice had bought some industrial cow ricotta just in case. Everyone tasted both of them except Beatrice. She said she didn’t like ricotta! I’m afraid I’m a bit of a bully when it comes to tasting, and finally she took a tiny spoonful of our goat ricotta. I wish I’d got a photo of the smile on her face. The industrial ricotta was a tasteless paste by comparison. We used our artisan ricotta, and the torta squisita, topped with a thin meringue, was truly delicious.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed