|

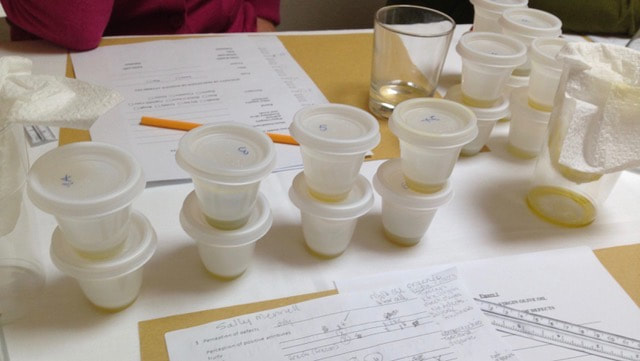

This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 28 January 2017. Did you know that olive oil is the only common cooking oil that is the juice of a fruit? All the other oils we use in our kitchen come from seeds: sunflower, rapeseed (canola), peanut and grapeseed. This realisation leads directly to another question. Would you cut an orange, leave it on the counter for a week and then squeeze and drink the juice? Would you step on an apple, leave it on the table for three days and then eat it? Yet that’s what happens to many olives before they’re pressed to extract olive juice. I’ve tasted and written a lot about olive oil, but this idea had completely escaped me until I met Elisabetta Sebastio last year. She’s a professional olive oil taster both for Italian Chambers of Commerce and international olive oil competitions. We ran our first full-day olive oil class during my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November 2016 (now we run a full course on the subject of olive oil: Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany). It was a revelation for all of us. We gathered around her kitchen table. She taught us how the professionals taste and rate oil. We tasted eight olive oils. The first was a surprise and I don’t want to ruin the impact by telling you what it was. Then there were four new-season oils: one from Sicily, two from Tuscany and one from the Abruzzo. Some people liked the tomato scent of the Sicilian one, others the bitter piquancy of the Tuscans. Lots preferred the less in-your-face qualities of the Abruzzese. Under Elisabetta’s guidance it was so easy and we were proudly feeling like experts when we started on the three defective oils. Wow! It was so clear that they didn’t measure up, and we could describe what was wrong with them: rancid, vinegary and fusty. We didn’t want to put them in our mouths. You’ll taste lots of mildly rancid oils in restaurants due to poor storage in clear bottles in the warmth. There were more revelations. Contrary to popular belief, true extra-virgin olive oil has the highest smoke point of any vegetable cooking oil. Another fact some people don’t realise is that it deteriorates with every passing day, even in a sealed bottle. If you’ve got some excellent oil, carpe diem. It will be worse tomorrow. But olive juice isn’t just for cooking. In Italy it’s mainly used as a condiment, like salt and pepper. This got us thinking about which olive oil goes best with which foods. Elisabetta had devised a lunch to demonstrate the classic pairing of regional dishes with an oil of the same region. We got to help prepare orecchiette (an ear-shaped pasta from Puglia) with an artichoke sauce seasoned with extra-virgin olive oil from Puglia. Sadly, we ran out of space in our stomachs before we could taste all the different dishes Elisabetta had prepared. I took another group to her home in December. One of them loved chocolate and Elisabetta assured me she could source some olive-oil flavoured chocolate. The platter of chocolates was beguiling and they tasted fantastic. She had made them herself! Join me on the course Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany from 18–23 November 2021 and meet the amazing Elisabetta and have fun with olive juice.

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here.

0 Comments

By Alison Goldberger 2020 is definitely a year none of us will ever forget, that's for sure. It all started off so promisingly with lots of excitement about meeting all of you who had booked on a tour or course! Of course we all know how it ended—with a year very difficult for a small tourism business. Although we were disappointed we had to cancel many tours and didn't get to meet you, we were buoyed by all your messages, interaction on our social accounts and hope you enjoyed the virtual tours we ran. And of course, it wasn't ALL bad, and Erica and I have survived the year in good health! So we'll start our review at the beginning, before we had even heard of the virus that would characterise the year... January One of our first posts on Facebook was this stunning photo taken from Erica's window. She captioned it: 'The view from my window. Must be a good omen for 2020!' It makes me laugh a little now looking back at this. As I said in the introduction, 2020 started off great! The Art & Science of Gelato course got into full swing and we welcomed the super talented Sorravee 'Gin' Pratanavanich. Gin had grand plans, after learning with us she was due to head off to take up a chef internship at a hotel in Abu Dhabi. Looking ahead, Gin would like to open a pastry shop and gelateria in Bangkok. We were also delighted to be able to run the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany in January. Two of our artisans met during this course, Mirko who leads the Art & Science of Gelato course learned how to make salami from artisan norcino Massimo Bacci. Mirko wasn't the only one learning however. We met lots of interesting participants during the January Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany. Here we see them learning all about knots. Knots are important to hold things in place and to squeeze air out. To produce a nice looking product, you need to tie tidy knots. And as you can see, our participants were taking this very seriously! On the blog in January we also shared a beautiful piece by Lin Hobley about her experiences of the Tastes & Textiles: Woad and Wool tour. Read it here. February February saw us on the Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma. We left Tuscany for Emilia (the northwestern part of Emilia-Romagna). This region of Italy is particularly famous for not one, but two delicious types of salumi— Prosciutto di Parma and Mortadella di Bologna! Check out the blog post here for more pictures and information about what happened during this tour in February! March March of course brought with it COVID-19, and in Italy things became serious very quickly! It was still an unknown entity in March, and we weren't sure how things would play out. We welcomed a couple of intrepid souls onto the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany in March, in what would be the last course for a while! We were still hoping that things would all blow over but were concerned about the impact the travel bans would have on those looking to come on courses and tours in the near future. Anyway, Australian vodka producer Katie Krauss and American head chef Seamus Platt joined us. They managed to learn everything the course had to offer before dashing off on the last flights home! Erica quickly had to get used to life under lockdown, long before many other countries started to introduce such measures. It did, however, result in her having a bit of an adventure! As flights started to get cancelled across Europe, one unexpected result was the car of some friends trapped in the Pisa airport car park, which was due to close. After calling in various favours the car was freed...read exactly how in the blog post here or click the car image above! It also allowed for a bit of cooking and exploring the beautiful surroundings outside her door. More information and pictures are here in the March round up blog post. Across Italy people started to pull together in the face of tough lockdowns, travel bans and an unknown virus. Many sang and played music from balconies and out of windows. Antonio Daniele, head cheesemaker at Caseificio Prime Querce, and one of the artisans who teaches our Mozzarella & its Cousins course made this graphic and said: 'We must withstand and fight. We'll come out of this stronger than before.' April In April we started to adjust to the new normal. For Erica, even cooking dinner turned into an epic adventure! This meal took her on a journey to remember people she'd met along the way and about the history of the ingredients. It really is a fantastic story, you can read the whole thing here - or by clicking the image above. Lockdown meant Easter alone for Erica, but her neighbours certainly wouldn't see her starve! She wrote in a Facebook post: "Under lockdown they couldn't invite me to eat with them. At 11.30 am the doorbell rang. It was Eugenia with three slices of pie with different fillings—rice, lemon and chocolate. At 12.30 the doorbell rang again. It was Daniela bringing her homemade tortelli and sugo. I was only planning marinated and grilled goat chops with cannellini beans and insalata with local red wine. Now I had a three-course lunch. Such kindness and generosity, and I certainly didn't feel alone." In April we also ran one of our first 'virtual tours' to give you all a taste of what you would have been experiencing, had you been allowed to visit Italy. We all travelled around Sardinia on the Celebrating Sardinia tour and had a great time! You can read the whole thing for yourself in the blog post here, or by clicking the image above. May In May we would have been running the Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, but that was not to be of course. So we also offered a little preview on Facebook. We visited Enea Giunti's goat farm and learned how to make fresh goat cheese. We stayed at Agriturismo La Torre at Fornoli and met Vitalina who shared her extensive knowledge of cheese making. We milked cows at Marzia Ridolfi's and drove up to Daniela Pagliai's to see her small modern dairy and how she makes a number of different cheeses from one pot of milk. And all this in the company of Maria Sarnataro, a real expert on cheese! Read all about what else we saw in the blog post here. The Tastes & Textiles: Woad and Wool tour was also meant to run in May, but instead we ran it as a virtual tour. It was a fascinating tour with so many interesting sights and photos, which you can see here in the blog post. June Another month and another virtual tour, this time it was the Tastes & Textiles: Hanging by a Thread tour. Card weaving, farm accommodation, vineyards, Garfagnana potato bread, knitting, felting, weaving, wonderful food, an ethnographic museum, a woolen mill - it was all there and more. Read all about it in the blog post here. After the tour Erica shared some of the delicious meals she'd been making. She had been experimenting with ricotta. The people who sell it in the open-air market won't sell a small amount. She has to buy a whole one. This spring she tried this simple sauce for short pasta made with fava beans (broad beans) and ricotta - delicious! The classic dish everyone around Erica makes with ricotta is ravioli. She said of this meal: 'I have a lot of chestnut flour in my freezer—gifts from friends who collect, dry and mill their own. I made pasta di castagna (about 1/3 chestnut flour) with a filling of fresh ricotta, young nettle tops, an egg, salt, pepper, nutmeg. The slightly bitter nettles contrast well with the sweet chestnut flour. The sauce is simple melted butter with fresh sage leaves.' This recipe in particular got my mouth watering! There is a self-seeded cherry tree hanging over Erica's orto (veg garden). In June it produces a small crop of mildly sour cherries. Every year she makes one focaccia with the cherries, but it never turns out exactly the way she wants it. Until this year. It's exactly the thickness and degree of sweetness she'd been searching for. Persistence pays off! July and August With some restrictions lessening in Italy, Erica took the chance to do some travelling! At the end of July she headed off to Pompei. She first saw the sights of Napoli and was welcomed by her collaborator on the cheese courses, Maria Sarnataro. First they tried some tasty delicacies, including the famous sfogliata. While in Pompei Erica hired a wonderful private guide, Francesco Tufano, an archaeologist who could answer all of her questions and more! Read all about the trip here in the blog post. The second half of Erica's trip took her from Pompei to Salerno where she and Maria visited some mozzarella dairies. She was very impressed when she visited Caseificio Barlotti and met brothers Enzo (pictured) and Gaetano Barlotti. She hopes to bring future participants on the Mozzarella & its Cousins course for a tasting in their beautiful garden. She had some samples of his bocconcini, ricotta and a new brie-style cheese, all made with the milk of their own buffalo herd. The mozzarella and ricotta are among the best she'd tasted. Read all about this part of the trip in the blog post here. Erica also took a research trip to Le Marche for the Tastes & Textiles: Woad & Wool tour. It's during these types of trips she meets the artisan's we visit on tours and finds the incredible restaurants we dine in! Perhaps you don't know where Le Marche is. Le Marche means 'The Marches', which in English refers to an area of land on the border between two countries or territories (eg, the Welsh Marches). In fact, Le Marche borders three other regions, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany and Umbria, with the Adriatic Sea to the northeast. Before the unification of Italy in 1861, they had a lot of borders and ports to protect, which means lots of spectacular fortresses and castles to visit! This photo above was one of my favourites from the trip, showing masked men waiting for their wives to finish shopping in Urbania. During the trip she also met some fascinating people, including Federica Crocetta, who has a passion for dyeing textiles with natural plant dyes, and Emanuele Francione, who learned the craft of textile block printing with rust from his grandfather. Read all about the tour in the blog post here. September In September Erica was back home, and making passata! You can read all about it in the blog post here, or by clicking the photo above. There was also some excitement for Mirko, who teaches the Art & Science of Gelato course as he opened a new Cremeria Opera just outside the walls of Lucca. Erica and Mirko had a little celebration...wearing masks of course! October In October Erica attended a fantastic lunch cooked by her favourite Lucca chef Damiano Donati. She said: 'His restaurant in the centre closed during lockdown. I was forlorn. Now he's popped up at Fattoria Sardi vineyard better than ever. He calls his fixed menu for Sunday lunch Fuoco e Materia (Fire and Matter). He was always fascinated by contrasting textures. Now he has a wood-fired oven in his kitchen and is playing with smokey flavours too, and it works. Here he is relaxing on the terrace after lunch. The dishes included: squash cooked two different ways and wrapped in chestnut leaf parcels, beetroot risotto, chicken stuffed with pork accompanied by smokey crushed potatoes. If you opt for the wine tasting, you get a different delicious biodynamic wine paired with each course.' There was also a little time to squeeze in some truffle hunting for a private tour! Truffle hunter Riccardo instructed Brendan in how to use three of his senses—sight, smell and touch—to assess whether the truffle is poor, mediocre or excellent. This 66 gram truffle is excellent, and after his truffle lunch with his wife and child, he decided to buy it so they could go on indulging in truffles for the rest of their holiday. We were also delighted to be able to hold a REAL LIFE Art & Science of Gelato course in October! We welcomed Niels, chef on a super-yacht. On the October course we teach how to make sourdough panettone as well as gelato so you know how to do it in time for Christmas. For his unique flavours Neils created pineapple and rosemary sorbetto, date and whisky gelato and Piña Colada sorbetto! November In November Erica went to Frantoio Lenzi to get her year's supply of olive oil. At the height of the harvest, frantoi (olive mills) are open 24/7 and it's always chaotic. She picked up bag-in-box new oil. You can recycle the box, but not the bag. However, by excluding air it keeps the oil from oxidising so rapidly and preserves the health benefits and the flavour for longer. The oil is fruity (tastes like olives!), medium picante and medium bitter. Her conclusion: a nice rounded flavour. 2020 would have brought us the first participants on our new Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany course, but it was not to be. Nevertheless, we ran a virtual tour to whet your appetite! Read all about it in the blog post here. December One of the most popular blog posts of the year was about the abandoned farm houses of Casabasciana. Wonderful photos and stories, can be seen in the blog post here. The year wound down with a poignant blog post featuring a video about the death of peasant farming. It was made by farmers in Umbria, but it could have been made anywhere in Italy—or in many other countries in fact. We visit many small farmers during tours and one of the things that was important when setting up Sapori e Saperi Adventures was to help preserve this way of life. You can watch it in our blog post here. After such a trying year it was nice for Erica to join her local community to decorate the village Christmas tree, a long-standing tradition which was just a little different this year.

We hope you have had a healthy 2020 and wish you all the best for 2021. We'd love nothing more than to welcome you onto one or more of our tours and courses. Get in touch with Erica at [email protected] for more information or for answers to any questions you may have. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This article originally appeared on Slow Travel Tours here. There’s a baby in the house. It’s my new-born olive oil course this autumn, on which you’ll find out how to get the maximum enjoyment from olive oil. Do you have any idea how exciting it is to visit an olive mill to see and smell the new olive oil pouring out? And what about the flavour? If you haven’t been in Tuscany in the autumn, you will have a hard time imagining how intense and delicious it is. Then there’s the food for your eyes: those old silver-haired beings rooted on terraces retained by dry-stone walling. Who will have fun learning about olive oil? Many educators focus on a particular group of people: chefs, gourmets, home cooks, dieticians, olive cultivators, olive oil vendors. They reason that each group wants to know different things, that their curiosity is confined to their own particular box. I have a different methodology and more faith in the innate curiosity of people. I always design my courses for the person I was when I first arrived in Lucca. When it comes to olive oil, I knew nothing except that some dishes should be cooked with it. I used a supermarket brand of extra-virgin olive oil, not the cheapest and not the most expensive. I didn’t know what I wanted to know. I didn’t even know what questions to ask. In my fifteen years in Tuscany, a whole universe of olive oil has opened up before me and yet there’s always more to discover. Just this week I visited Pietro Barachini, a propagator of olive trees. I saw the forest of tiny cuttings which would be ready for sale only after two years. Then it takes ten years or more for the tree to be in full production. Producing olive oil is not instant gratification! What about tasting the oil? What is that medium-priced supermarket extra-virgin olive oil missing (is it even really extra virgin)? What defects can you taste in it? Every day you have guided tastings. You won’t become an oil judge overnight, but you’ll discover a brand new palette of flavours from the fruity tomato-leaf scented Sicilian oils to our spicy, bitter Tuscan oils. Your mind will be racing with ideas for using different oils with different ingredients. Your lessons making gelato and chocolate with olive oil will stimulate your creativity. We also want you to know about the health-giving aspects of olive oil. They make a significant contribution to the Mediterranean diet and are another good reason to consume high quality oil. You’ll also get answers to your practical questions, like how to find good olive oil in your own country, what the writing on the label means and how to store the oil to slow down its deterioration until next year’s new oil is available. If you want to learn in five thrilling days what it has taken me fifteen years to find out, come on the Olive Oil: Tree to Table course this autumn. It’s taught by Elisabetta Sebastio, a professional olive oil taster and judge, sitting on panels that decide which oils will get the highly sought-after DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) each year, along with several other experts who want to pass on their knowledge at whatever level you’re at from beginner to experienced professional. By the end you could be jumping up and down with excitement at having the tools and confidence to make your own choice of which olive oil to buy and how to use it in your home or your restaurant’s kitchen. If you sell olive oil, you’ll be able more intelligently to advise your customers. If you’re a producer, you’ll have the opportunity to talk with experts. The culture of olive oil will be in your blood.

If you have an open mind and an insatiable curiosity, ask for a booking form now: [email protected] If you’d like to read more about olive oil, here are some of my other blogs: Olive Juice, No Olive Oil, Olive Oil is Fast Food It was the olive harvest of November 2004 that set me on the path to creating Sapori e Saperi Adventures and organising my special type of slow travel tours. Ten years on there will be very little olive oil from Lucca. To find out about the Tuscan olive oil disaster, please read my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website, a group of independent tour organisers like me.

http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/no-olive-oil/ The 2014 Slow Food guide to the extra-virgin olive oils of Italy is out. Since the 2013 harvest 130 Slow Food collaborators have been working hard to assess more than 700 farms and over 1000 different oils. Like wine, some vintages of olive oil are better than others: 2012 was a great year for Lucca oil, but 2013 was particularly difficult, producing less characterful oils. Nevertheless, the guide recommends nine oils from Lucca Province. To read more about olives and olive oil, please go to my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/extra-virgin-lucca/

Oxidation isn’t usually a hot topic of conversation. When my 1968 MGB GT was rusting away, I discussed it at length with the vintage car body shop, and I submerge peeled potatoes in water to prevent them going brown, but dinner parties don’t usually include riveting exchanges about the interaction between oxygen molecules and the substances they contact. In the olive grove, however, oxidation is the dragon that would ravish the extra-virgin oil, filling it with free radicals and a rancid flavour. Everyone talks about it. Picking olives and pressing the oil has been a popular activity for many of my clients this autumn, and for our hosts Augusto Orsi and his son Claudio of ‘Alle Camelie’ avoiding the evils of oxidation is what determines the way they pick and press the olives. Their estate abuts the olive terraces of some neighbours who conduct the olive harvest in the old way. Augusto points to nets spread on the ground under the trees to catch the olives that drop during the weeks before they begin their harvest. He shudders slightly as he explains, ‘The moment an olive is detached from its branch, it begins to oxidise. It needs to get from the tree to the bottle really fast. We put our nets down under a few trees, pick the olives, move the nets along to the next trees, pick the olives, etc. Hard work, but the flavour of the oil makes it worthwhile.’ When his neighbours do begin to pick their olives, they beat them off the trees with bamboo poles thus bruising the olives and sometimes breaking the skin, allowing the fruit to oxidise even more quickly. Augusto, Claudio and their four farm labourers pull each olive off by hand. We help pick from the ground, but the other harvesters are often at the top of a ladder propped against the tree or standing on one of the thick branches to reach the olives at the top. Augusto would probably say, ‘Time consuming, but the flavour of the oil makes it worthwhile’. The harvested olives should be pressed as soon as they are picked. Some estates invest in a small, though expensive, olive press and press olives on the day they’re picked. Augusto takes his to a co-operative modern frantoio every other day, but is thinking about buying his own. [He did the following year.] Pressing the olives at a traditional frantoio is tantamount to delivering the maiden to the dragon’s den, where the huge picturesque grindstone rolls round and round crushing the olives in a huge open basin — 45 minutes of exposure to oxygen. Then the paste is smeared onto woven mats, stacked on a spindle and pressed to squeeze out the oil. Old dry, oxidised paste sticks in the crevices of the mats and oil runs out around the edges exposed to the air. In a modern continuous-method frantoio, the grinding takes only a few minutes in a closed container, and the paste is pumped into a closed vat where it is heated very gently to release the oil which runs into a stainless steel container with a well-fitting lid. Take a deep breath filled with oxygen, and taste the oil from ‘Alle Camelie’. The magnificent flavour certainly justifies the care they take to avoid oxidation.

I’m sitting round Franca’s kitchen table, already populated by her husband Peppe, their married son Marco, and Carlo, a builder and work colleague of Peppe’s. Carlo, always jolly and looking well-fed, observes with a sly smile that you can buy ‘extra-virgin olive oil’ in the supermarket for €1,80 a litre. He pauses for dramatic effect, and Franca, taking the bait, says she pays €8; she looks uncertain about admitting she may have been cheated. Carlo immediately supports her. ‘Of course it’s not extra-virgin. How could anyone produce extra-virgin olive oil at that price? You can’t believe it just because it’s written on a label. The cheap stuff is made from the remains of the first cold pressing by adding chemicals and heating it up to extract more oil. It doesn’t have any aroma or flavour at all.’ Franca looks relieved; she buys hers from a woman who comes to the village every year with her new olive oil. She doesn’t even ask to taste it anymore, because after so many years she trusts the woman to supply oil she knows she likes. But if you want to taste oil, Carlo’s recommendation is that you toast a piece of bread and drizzle it with oil while it’s still warm, thus releasing the aroma and flavour of the oil. Franca and I favour pouring a little puddle in our palms and leaving it to warm before slurping it up while also sucking in some air. At olive oil tastings I’ve been given oil in a little plastic cup to warm in one hand with my other covering the cup to keep in the perfumes that are released by the warmth of your hand. Before smelling, you position your nose close to the cup and when you remove your hand, you’re hit by the pungent odour of crushed olive — or not, if it’s a poor oil. Besides the synthetic oil, Carlo’s bad category includes oil that burns your tongue, which in his opinion includes Lucca oil. One of his favourites is a mellow oil from Montecatini. Here I disagree. I love the early oil pressed from olives harvested in October on the Lucca plain, peppery on the tongue and a little bitter at the back of the throat. Carlo insists, ‘The olives have to be completely ripe, black. Then the oil is sweet and mellow. The best is from Genova.’ I’ve tasted Ligurian oil and agree its delicate flavour is well suited to the fish that forms a large part of the diet in that coastal region just to the north of us. Even the Genovese basil is more delicately flavoured than our Tuscan variety, and no self-respecting LIgurian would make pesto from our hard-hitting leaves. We finally agree it’s all a matter of individual taste — ‘a ciascuno il suo’. Walking home, I reflect that my sophisticated oil-producing friends stereotype old farmers, who harvest their olives from late November onwards when they’re fully ripe, as ignorant or greedy. They’re only simple peasants who wrongly believe they’ll get more oil from riper olives and care nothing about the flavour. It never occurs to modish followers of fashion that their traditional neighbours may have just as well-developed palates, and after analysing the old and the new flavours, decide that what they’re used to is best. What do you think?

Super-highways rarely belong to the country they’re in. While racing along with cars and lorries overtaking on all sides, you could be anywhere, except for the blurred glimpses of houses or fields beyond the crash barriers. The village of Molina di Quosa tumbles like a stream down a mountain valley and spreads out on that ribbon of land squashed between the Serchio River and the hills of the Monte Pisano overlooked by the autostrada and the railway that link Lucca to Pisa. And that’s all I knew about it despite my many trips between the two cities. Now a couple of friends and I were heading there at a sedate pace on a small twisting country road for a festival based around new olive oil and chestnuts, vintage cars and Vespa scooters, with a wild mushroom exhibition thrown in for good measure. [November 2020: Due to the perversity of IT, several years ago all the photos were stripped off this blog. Most have also disappeared from my photo library and that of my friends, in particular nearly every photo of olive oil. Here you see what the microchip demons have chosen to leave behind.] It must be a winning combination since before we even reach the village, parked cars line the verges and coming into the village itself we nose up to a queue of stationary cars held up by a policewoman to let the crowds cross the road. We abandon the car in a field that has been requisitioned as the festival car park and walk back along the main road, passing several large elegant villas skulking behind high walls and heavy iron gates. I must read that history of Pisa, in Italian, that I bought at Pisa airport in one of my fits of wanting to know everything about everything between the sea and the Garfagnana. It might explain why anyone with money and status would have wanted to live on the Serchio River bank kilometres from anywhere. The original main street of the village runs perpendicular to the road we drove in on, up the side valley. We turn up it between shops and houses on one side and, on the other, stalls selling craft jewellery, kitsch wooden carvings and honey. After a porchetta stall (we make a mental note to return for lunch), we come to the first roasting chestnuts and the first olive oil stall. The signora tells me that her olive groves are at Montemagno, but she takes the olives to the frantoio (olive mill) at Vicopisano which is an excellent modern press. The olives were picked yesterday and pressed and bottled early that morning in time for the festival. The owner of the olive press arrives just in time to verify both the quality of his frantoio and the timing of her pressing. She offers me a slice of bread doused with oil — these oil anteprime (previews) are the only times I’ve ever seen oil poured over bread in Italy, but I notice a stack of small plastic cups and ask to taste the oil in one of them. She agrees this is the best way to taste the oil, but ‘many of us’, she circles her hand to encompass the anonymous bystanders, ‘are ignorant’. She pours a small puddle of thick green oil into the cup. I hold the cup in one palm to warm it while keeping the other hand firmly clamped over the top. After a minute or so, I put the cup to my nose and raise my hand enough to sniff up the pungent aroma. Then I slurp up some of the oil with lots of air and taste the strong heady flavour, bitter at the edges and peppery at the back of the throat. The most interesting producer for me is a young man who is offering comparative tastings of his last year’s oil and this year’s, also just pressed that morning. But these first few bottles contain oil only from the bitter leccino variety of olives, since they’re the ones at the top of his slopes and ripen earlier than the sweeter frantoio and moraiolo lower down. Last year’s bottles contain a blend of all three varieties, and have a decidedly gentler flavour, partly due to the blend and partly a result of ageing in the bottle. His azienda is organic and he’s joining forces with some other producers, including a norcino (pork butcher) to present taste workshops. He invites me to visit.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed