|

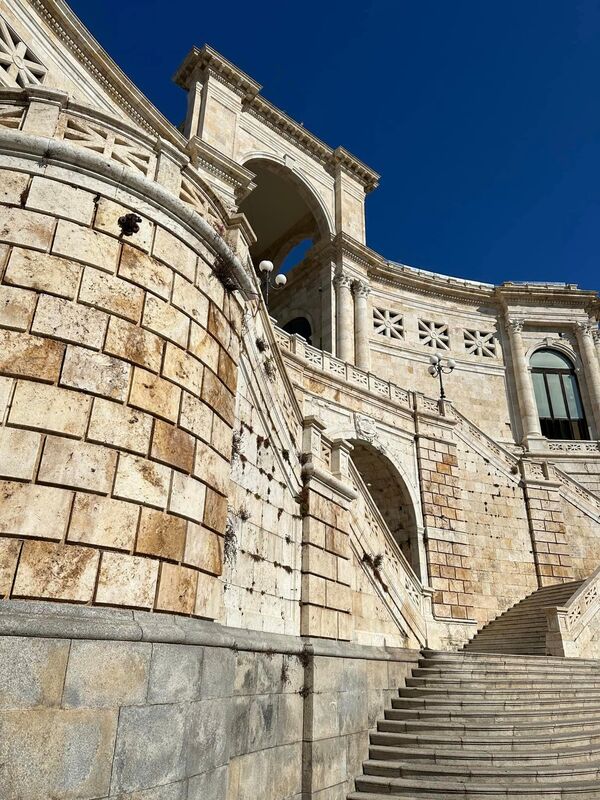

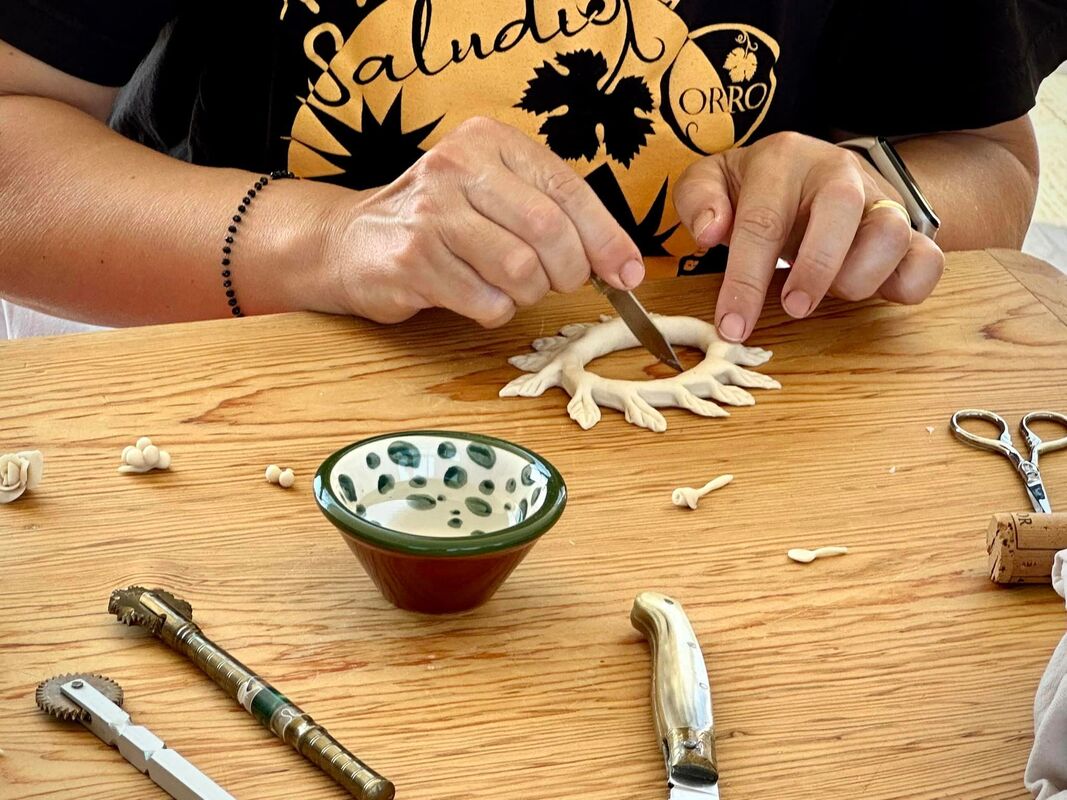

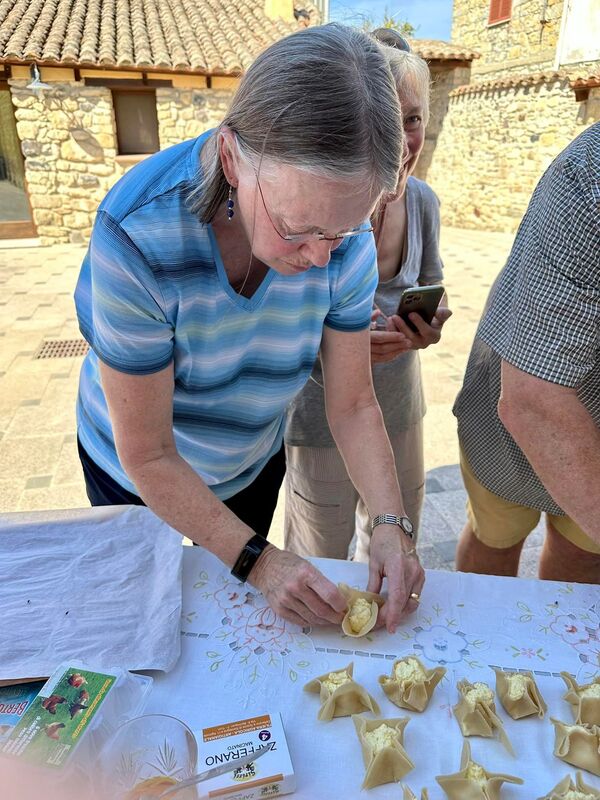

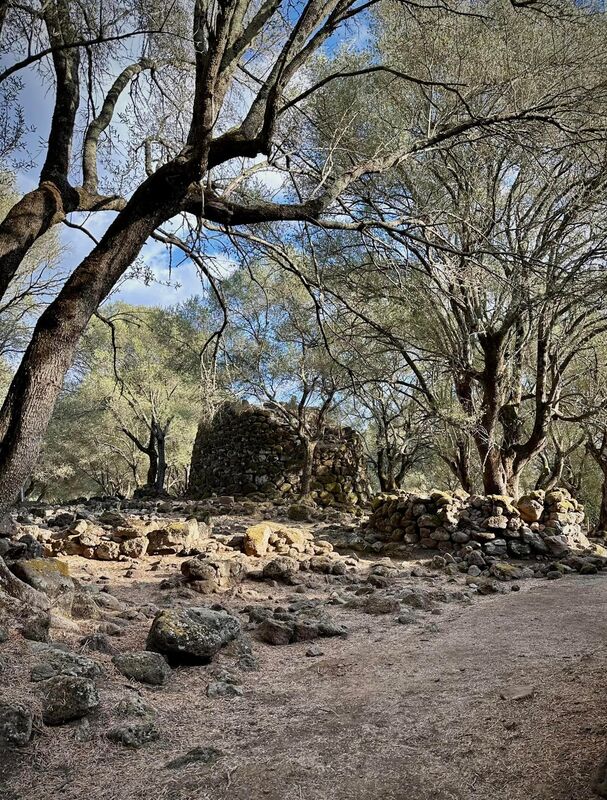

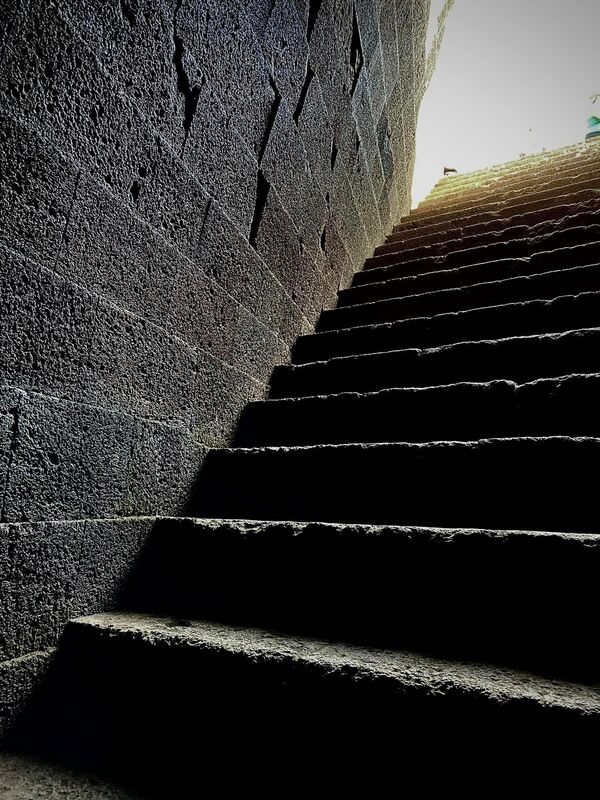

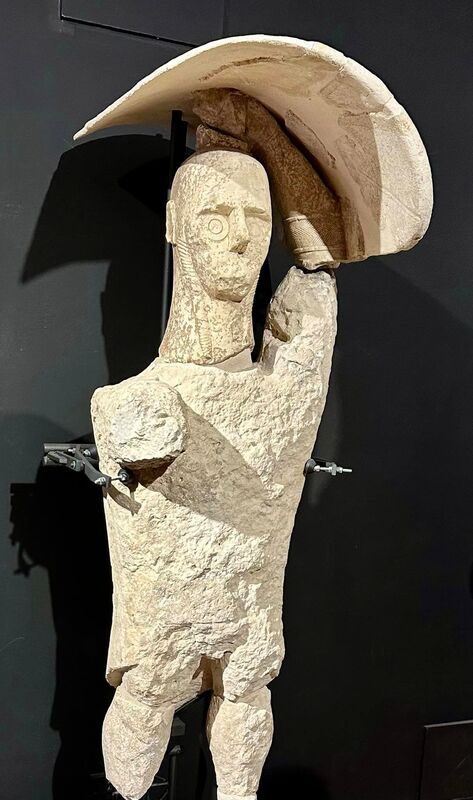

It's always wonderful to travel to Sardinia, but during the recent tour Erica had a special guest—her cousin Jeff Blaine who had travelled with his wife Sue from Chicago to join the tour. Jeff & Sue also happen to have a talent for photography so we are delighted to be able to share what they captured during the tour. (Except where indicated, the photos are by Jeff.) Our Italian adventure begins with food and family… Cagliari is the capital city of the Italian island of Sardinia…Bellisima! Mercato San Benedetto Visiting the Museo Archeologico Nazionale Explorations in the Sardinian Nuragic civilisation… Olives, Bread and Wine with the Orro Family and sightseeing in Oristano… Rice and Cheese! Culinary adventures in Sardinia… We’ve always wondered; now we know… how the sausage is made! Food & Archeology… Culurgiones ogliastrini & Nuragic ruins… Nuragic giant & farewell to Sardinia This was all part of the Giants of Sardinia tour which will be taking place again from 28 September –5 October 2024. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. Other blogs about Sardinia: Cross-Dressing in Sardinia, Sardinia and its Giants

0 Comments

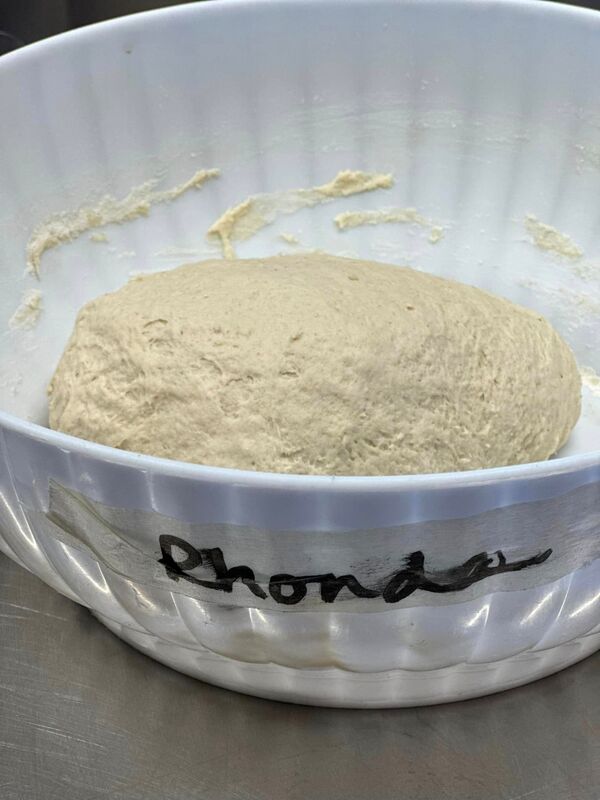

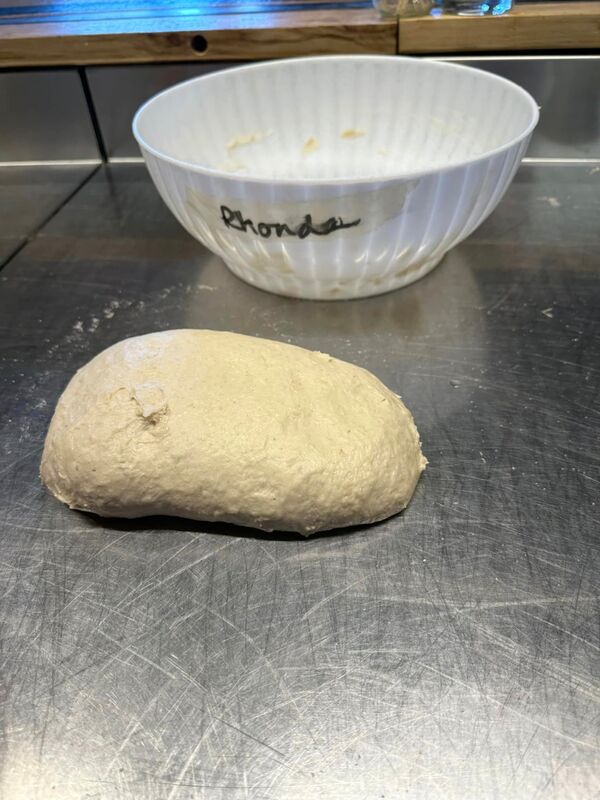

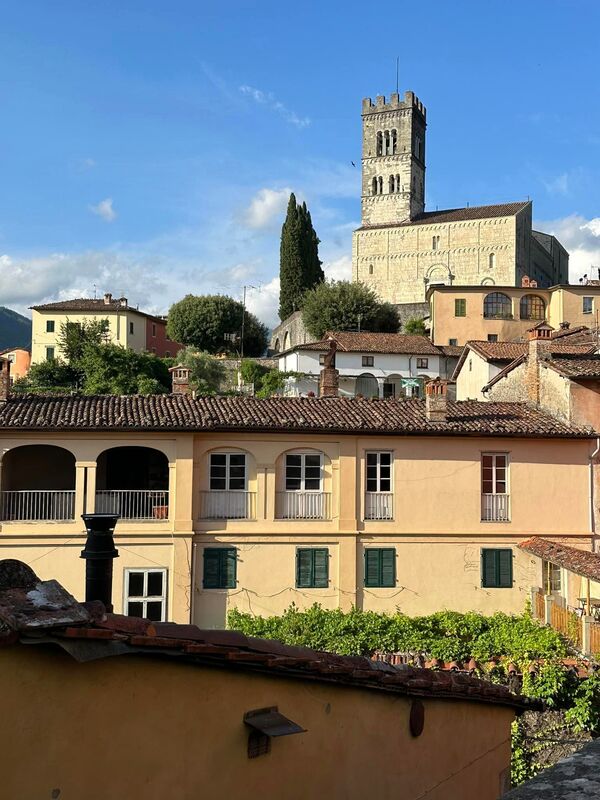

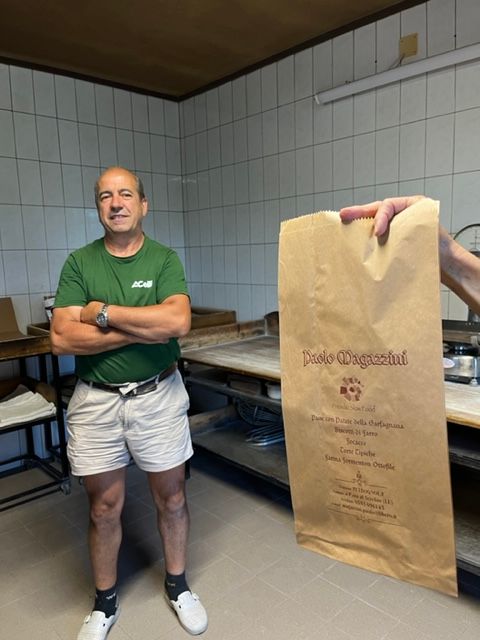

Rhonda Gothberg, a goat farmer and cheesemaker from Washington State, USA, joined us on the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany this year. She shared wonderful commentary and photos online during the course and has allowed us to share them with you in this blog post. We have put together her comments and photo captions below. Enjoy! First a note from us: Rhonda had travelled around Italy before joining the course, which began in Hotel Park Regina, Bagni di Lucca.  Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Arrived at our hotel. It’s an old classic. Maybe not for everyone but I like it. Very friendly desk help to me, the newbie. Sourdough bread making today with Chef Damiano at Fattoria Sardi. We were also treated to lunch there. We go back tomorrow to bake the bread and another lunch. Oh my goodness...all around excellent. A highlight today is a visit with Carlo. He’s 85 years old. His family has been blacksmithing for over 500 years. Sadly, no one is coming up behind him. This place is fascinating! It is run completely on water power. Such a skilled master artisan. We were all mesmerized. Today we worked with Chef Damiano again and got our bread baked from yesterday. We then had a tour of Fattoria Sardi vineyards and wine areas. We learned to make our own sourdough starter. Then another fabulous lunch. After that we visited a farmer who grows ancient varieties of wheat. A brief rest at the hotel then out to dinner for pizza and a beer. We learned to make these yeasted flat breads [Ed.--fogaccia leva di Gallicano] yesterday. These are made on traditional flat iron sort of griddles. Some call the pan testi but there are other names [Ed.--cotte in Gallicano] depending on the village tradition. Our hosts have been best friends since birth. What a duo! The ensuing lunch with this traditional food was really good. It is served with a local bean and sausage ‘soup’ [Ed.--fagioli all'uccelletto, a traditional Tuscan bean stew]. Then they taught us a version made with chestnut flour [Ed.--necci] and rolled around fresh ricotta. After this, we went to another village to learn the same technique for one with no yeast or rise, a mix of flour and cornmeal [Ed.--criscioletta of Cascio], with strips of pancetta cooked into it. Needless to say no one was hungry for dinner. A flour mill that is still driven by water. Note that the water wheels are horizontal. They made the flours for our flatbread class. Then on to more beautiful places. Rhonda was unable to take part in the final day of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany. If she had she would have learned about the Slow Food Presidium Garfagnana potato bread with Paolo Magazzini. With a visit to Paolo's farro polishing machine and free range beef cattle during gaps in bread making. Topped off with a lunch cooked by Paolo's wife!

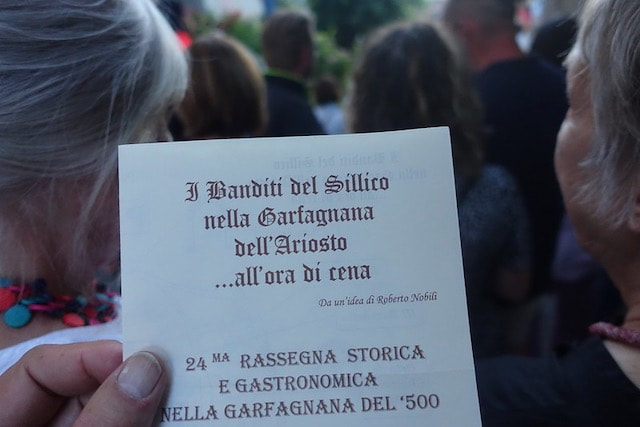

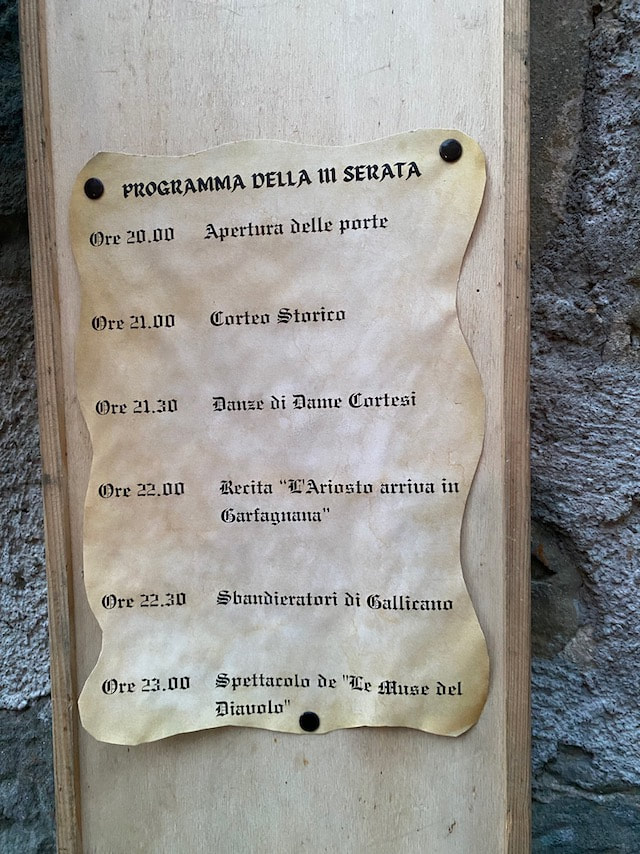

This was all part of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany, which will be taking place again from 11–16 February. It used to be in July, but it's too hot now to do anything, much less bake bread. Find out more here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. 'The Bandits of Sillico in the Garfagnana of Ariosto ...at dinner time'. The translation into English of the title of this historical and gastronomic festival leaves most of the story untold. As you'll see below, the real joy is in the way this tiny mediaeval village works together to present a spectacular meal and show. But you'll need a bit of local history to get into the spirit. In the 1400s the Garfagnana (the mountainous region north of Lucca) wanted to free itself from the tyranny of the Republic of Lucca and asked for help from the Este family, the Dukes of Ferrara. The Dukes obliged and installed a governor at the region's capital, Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. In 1522 they sent the poet Ludovico Ariosto to fill the post. He hated all three and a half years he spent there, especially his dealings with the local brigands whose chief was Moro of Sillico. When Ariosto arrived, they essentially ruled the Garfagnana. Being a poet, he wrote many letters to the Duke complaining about their activities and asking for more troops, and through his descriptions we have a lot of detail about the brigands. To this day Castelnuovo vaunts its noble governor while Sillico brags about how Moro outwitted him. I know the back route to the upper gate where the queue is shorter. The entertainers are arriving too. Here's Giulio, director of the Sbandieratori and teacher of our fogaccia di Gallicano lessons, another tradition he's helping to preserve. Let me quickly brag a bit on Giulio's behalf. His troop has performed throughout Europe and is known for its fast, explosive and unpredictable style. It has won the national championships more often than any other group. Bravi! 8.00 pm—Opening of the gates 9.00 pm —Historical procession 9.30 pm—Dance of the courtly damsels 10.00 pm—Play "Ariosto arrives in the Garfagnana" (spoiler, Moro wins the poetry competition improvising in ottava rima) 10.30 pm—Sbandieratori di Gallicano 11.00 pm— Show "The Muses of the Devil" (wish I had the stamina to have stayed for this) Now we climb the steep cobbled streets to arrive at the terrace where the main course is served. This is Nadia. Her husband Bruno lights three metati (chestnut-drying huts) every October and I often take my salumi course participants to see how much work goes into producing the naturally sweet chestnut flour of the Garfagnana. Festivals are good places to meet old friends. The quickest route to the piazza where the shows take place is through Palazzo Carli where we are catapulted from the 16th century into the 19th. We come out of the palazzo to a spectacular show in the piazza in front of the house where Moro was born. We climb to the top of the village to arrive at the fourth banquet: dessert. I'll leave you with the sound of the bagpipers. Thank you to Klaus Falbe-Hansen for supplying most of the photos in this blog and to him, his wife and their friend for accompanying me for this thoroughly enjoyable evening. By Alison Goldberger This year marked the 150th anniversary of the Carnival at Viareggio and Erica was there taking it all in…and of course taking some photographs too. The Carnival has been taking place since 1873 and involves many highly decorated papier-mâché floats and masquerades traveling in a procession down the ‘passeggiata’, or promenade along the seafront in Viareggio. It sounds like fun and games, but it’s a serious business. The floats take part in four ‘classes’ and creators can move up and down classes depending on how many points they are awarded for their creations. Moving up or down a class can make or break the designers. The four classes dictate the size and budget of the float and the order in which they travel. As you can see from the photos, the floats are huge and take months and months to build. There are of course many light-hearted and fun floats, and this year some celebrated the 150th anniversary. However, they are often allegorical, and this year touched on the war in Ukraine. A huge gorilla adorned with military medals entitled 'The Evolution of the Species' represented war and misery. There was a stark juxtaposition between the jolly celebrations of the anniversary and heavy anguish about the future of the human race. The photo above shows ‘Armed Peace’ by Alessandro Avanzini – a young girl wearing a helmet and gas mask. Her coat opens out into a flag of peace, symbolising the hope for peace. The final day of the Carnival (February 25) will also take on a political note with an 'Orangemob' - orange fireworks in protest against gender based violence. The announcement of the winning float follows!

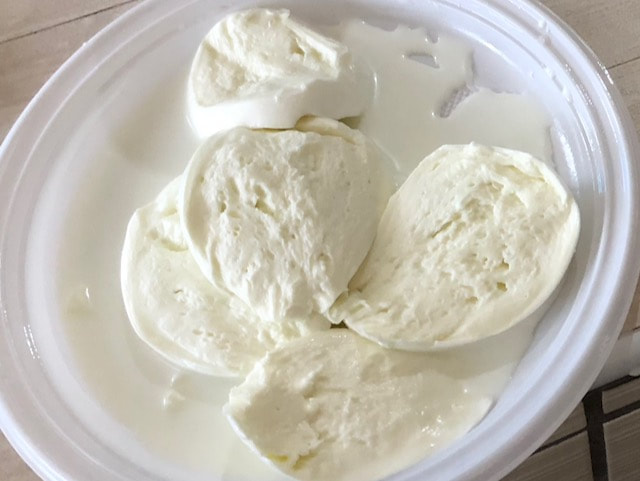

It is always a spectacular event. If you would like to read more about Carnival take a look at this previous blog post. Carnival traditionally ends on 'Fat Tuesday' or Martedì Grasso, if you'd like to read more about that, check out this previous blog post. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. By Alison Goldberger We hope you enjoyed our round-up of 2022. Perhaps it whetted your appetite for our tours and courses and you're thinking of joining us this year? We are already looking forward to meeting you! But first, let’s take a look at what’s in store in 2023… FEBRUARY Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma Our salumi courses are always the first of the year – winter is the best time to make salumi of course! Many of our artisans use traditional methods to air dry their products, so cool weather is a must. If Prosciutto di Parma is your thing, you could take our last space on the Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma in February. This course also teaches Mortadella di Bologna as well as some niche products – nose to tail at its best. This will be the only time this course runs in 2023, the 2024 date is still to be announced. MARCH Mozzarella & its Cousins The Mozzarella & its Cousins course is a professional development course teaching cheesemakers how to make pasta filata cheeses – mozzarella, scamorza and burrata (just reading it makes your mouth water, right?). For those of you who don’t happen to have buffalo milk at hand, we also take a look at the differences when using cow’s milk. This course will run in March, and there are still a couple of spaces left. It might run again in July and October, so please get in touch if you can't come in March. Art & Science of Gelato Create your own flavours, use professional machinery and get into the nitty gritty of sugar and fat content and how that translates into the perfect scoop during the Art & Science of Gelato course. Mirko Tognetti runs one of the top gelaterias in Italy and is passionate about natural gelato and sharing his knowledge. He also shares his insights into the business side of things. This course has availability in March, August and October. In October we also learn how to make panettone with a sourdough starter. APRIL Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese Join us in April on this professional development course which gives artisan cheesemakers the chance to expand their knowledge through working with five Tuscan cheesemakers. The Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course teaches various cheeses including lactic-coagulated goat’s milk cheese, rennet-coagulated cow, sheep and goat cheese and ricotta. Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese Extension The two-day extension introduces you Parmigiano Reggiano cheese at Caseificio Santa Rita Bio in Modena Province. They make parmigiano from the milk of the indigenous white Modenese cow. At the dairy we have the invaluable opportunity to see the whole process from milk to brining with all questions answered. And a tasting of their spectacular parmigiano of several ages from one year up to ten years. Celebrating Sardinia This wonderful tour is always popular and is fully booked for 2023, but there are places left for the April 2024 tour. During the Celebrating Sardinia tour our guests arrive during the Sardinian feast for their patron Saint Antioco and are thrown into the island’s colourful food and culture during two days of street parties. After the party there are many more interesting things to discover – pecorino cheese, salt pans and a day on a fishing boat to name but a few. MAY Tastes & Textiles: Woad & Wool During this tour in the picturesque borders of Tuscany, Umbria and Le Marche (a dream landscape!) you have the chance to dye with woad, block print with rust, visit the makers of Casentino wool and cook local specialities. The Tastes & Textiles: Woad & Wool tour allows guests to delve into living traditions and meet the makers who have been creating these very special crafts for generations. This tour will take place in May, and there are still some spaces available. JUNE Tastes & Textiles: Hanging by a Thread Join us in June as we visit the last of the textile artisans using methods handed down through generations. Tastes & Textiles: Hanging by a Thread 2023 also includes a new activity – making sandals with a luxury-market shoemaker. It goes without saying, there will be delicious food too, and various cooking lessons from our artisans who invite you into their homes. JULY Artisan Bread Course Tuscany Real. Bread. Need we say more? Okay, maybe a little more then. Five artisan bakers share their knowledge through hands-on classes during the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany. Think sourdough, focaccia, pizza, heritage grains, wood-fired ovens and the very special Garfagnana potato bread. Travel back home inspired. This course will run in July. AUGUST Tuscan Heritage August sees us hop aboard a time machine for a journey into Tuscany’s past. A few of the highlights of the Tuscan Heritage tour are hunting for truffles with an Etruscan dog, feasting on Palaeolithic beef and 14th-century pork, gazing at the countryside from a 16th-century fortress and tasting Chianti Classico wine from 17th-century terraces. Divine! SEPTEMBER Tastes & Textiles: Wine to Dye For This popular tour is full for September 2023, and we're now taking bookings for September 2024. During the Tastes & Textiles: Wine to Dye For tour we visit Pistoia and Pescia and try our hand at weaving baskets with marsh reeds, making watermarked paper and using wine as a mordant to dye leather and fabric. Tastes & Textiles: Sea Silk in Sardinia This 5-night Tastes & Textiles: Sea Silk in Sardinia tour takes us in search of the truth about byssus, or sea silk. The dark brown beard of the giant mollusc Pinna nobilis shimmers like gold thread when cleaned, treated with lemon juice and viewed in bright light. We visit the last remaining byssus weavers – a special experience. SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER Giants of Sardinia Off to Sardinia once more in October for the fully booked Giants of Sardinia tour. In 2024 this tour will run from September 28 – 5 October and is available to book. This tour encompasses Bronze Age stone giants as well as the giants of Sardinian cuisine – what a combination! NOVEMBER Autumn in Tuscany The delightful Autumn in Tuscany tour is fully booked for 2023, but available to book for November 2024. The sweet smell of roasting chestnuts, wood fires, new olive oil, truffles and new wine in the cellar. An indulgent dive into the traditions of the area and a culture seen through the eyes of local artisans. A season to remember. Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany Just as the year begins with salumi, so it will end. In November we will once again visit the artisan norcini of Tuscany during the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany. We glean their knowledge of making sausages, salami, Lardo di Collonnata IGP, pancetta, prosciutto and sopressata as well as many other delectable items. It’s a practical course and you can come armed with your notepad and camera to return home ready to make these products yourself, or vastly improve on what you currently make.

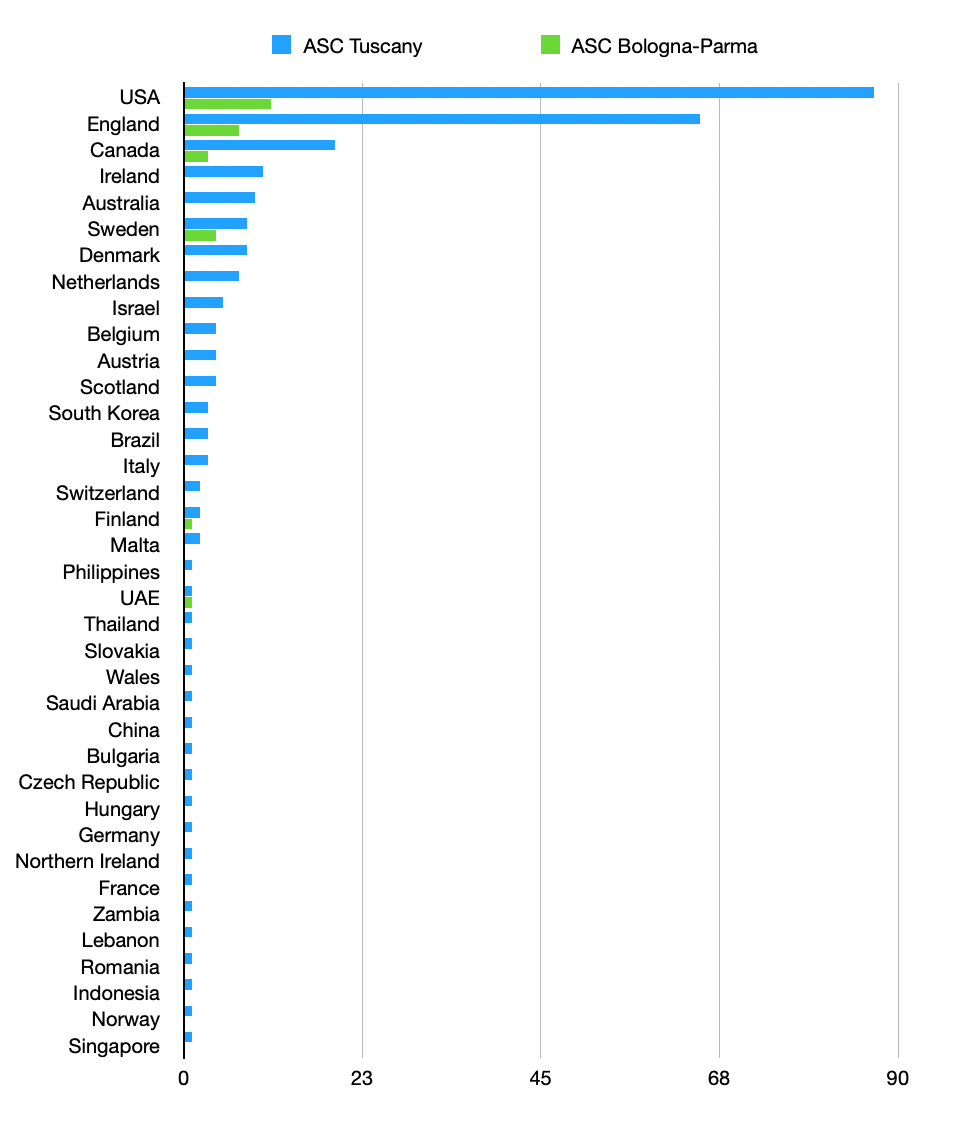

If you’re feeling inspired to join any of our tours and courses in 2023, or indeed to book a place in 2024 for some of this year's fully booked tours please get in touch with Erica. Find out all you need to know about each tour and course on the website. Our Facebook and Instagram pages will keep you updated with current tours and give you an insight into what to expect when you join us. We hope to see you soon! If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. I'm much more interested in quality than quantity. But since we have only two confirmed bookings on the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany in January 2023 and none on the March course, I've begun to wonder whether the market is saturated. Has everyone on the planet who wants to make Italian salumi already done our courses? How many courses have we actually run since the launch in November 2010? Should we be celebrating our 50th course or is it more or less? I admit I got a bit obsessed with the numbers. And I'm surprised by the results. Total number of Advanced Salumi Courses Tuscany: 48 since launch in November 2010 Bologna-Parma: 7 since launch in January 2017 Total number of participants Tuscany: 246 Bologna-Parma: 27 Pretty impressive, but what really surprised me were the number of nationalities represented by the participants. Thirty-seven countries! You'll notice a little cheating: the four 'kingdoms' of the United Kingdom are tallied separately, but I was curious about how many people came from each. Now I wonder: have we contributed positively to international relations? Purely in terms of numbers the US outdistances the rest, but as a percentage of the total population England must be the winner. When I first moved to Cambridge (England) in 1967, there were several dedicated pork butchers in the town. I don't know of any now. Perhaps today's butchers, pig farmers and chefs yearn to re-establish that tradition of curing pork but in a manner reflective of our more international outlook. In the realm of salumi, by which I mean dry cured pork as opposed to cooked dishes so common in France, no nationality merits emulating more than the Italians. Returning to the question in the title: how many salamis? I don't have a record of how many salamis our participants have made over the years. Hundreds? Thousands? So, is the market completely saturated? Or is this just the lull in the eye of the storm? Are bookings for February 2023 in Bologna and Parma and March in Tuscany about to come flooding in? These are questions for you, my readers. If you'd like to be on the mailing list for our salumi courses, click here: http://eepurl.com/hVwz6 If you're not already on our blog mailing list, you can sign up here: http://eepurl.com/geSMLv Some other salumi blogs from the early days of the course you might be interested in:

Moments of Glory From Pig to Salumi Salumi Course in Tuscany February—Learning the Art of Prosciutto in Emilia By Alison Goldberger As 2022 comes to a close, we would love to share our adventures with you. We were delighted to welcome so many visitors back to Italy to share in the knowledge of our artisans and take part in our tours. We kicked the year off with a classic, the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany. Read on to find out what else the year had in store for Sapori & Saperi Adventures… January The first course of the year still had an air of Covid around but regular testing meant we could carry on as normal. We visited Massimo Bacci and enjoyed the delicious Lardo di Colonnata by Fausto Guadagni. Illness in the family of one of our artisans led to a last minute change…bread baking! After 18 years in Italy, Erica has learned the Italian art of improvisation. A quick phone call and we were off to Paolo Magazzini to learn how to make Slow Food Presidium Garfagnana potato bread in a wood-fired oven. The last artisan of the course never disappoints. Here’s Gino Rocchi air drying some pancetta outside his incredibly scenic Salumificio. During a visit to Gino we see the whole production run. It's a wonderful experience. February Annabel loves crafts, so we took her and her mother to the Museo della Carta (Paper Museum, Pescia) for a watermarked paper workshop. She caught on so quickly, that they offered her an apprenticeship. Too bad she had to go back to school in the States. February also brought with it the Mozzarella & its Cousins course. We had rethought the course, deciding it was too complicated, even for experienced cheesemakers, to learn both mozzarella traditions in Campania. We reluctantly abandoned the excellent dairy in Caserta and added a new one in Salerno Province. We were a bit jittery at first, but Tenuta Chirico turned out to be a joy to work with. We got to make our own pot of mozzarella. The best learning experience possible. We enjoyed meeting Rodolfo (pictured centre), whose dad and uncle were both cheesemakers. He thought he wanted to learn something different. However, summers spent in dairies inspired a love for cheesemaking and he’s now the head cheesemaker at Chirico. He’s a great teacher too…lucky for us! Of course the Art & Science of Gelato course saw us pay a visit to Mirko Tognetti, owner of Cremeria Opera in Lucca. Gary Mihalik was already an experienced gelato maker, but he wanted to do a private course with Mirko to find out what he didn't know. There was fast and furious conversation in the classroom and the lab! Gary also got to try out the Cattabriga EFFE 6 – a vertical batch freezer, something he'd always wanted to do. Dreams really do come true… March Another month, another Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany. Here we are at Agriturismo Venturo preparing the filling for salami. Ismaele Turri teaches on this part of the course—butchering the pig, the Modena cut, shaping the prosciutto and spalla, pancetta, salting whole pieces. And the women on the course saluting all women on International Women’s Day under the flag of peace. Peace was also on the minds of the locals in Erica’s village of Casabasciana. They gathered together to enjoy a dinner to raise money for Ukrainian refugees. They raised €600 to put towards helping refugees living in Bagni di Lucca. Bravi! April There was a special half-day Art & Science of Gelato course in April, with one of our guests Barbara creating a genius flavour! Peanut butter, chocolate and meringue. So good it was on sale in Cremeria Opera. Then, after a two year break we were back in Sardinia! Our group received a very warm welcome from Roberta and Aurora at the Gallo Bianco, Erica's favourite hotel in Cagliari. A very welcome first toast of the tour. It was good to be back! May Even Erica can find something new to enjoy on the tours. During the Celebrating Sardinia tour she noticed something she’d never taken in before. She has watched the decorated oxen yoked together pulling the traccas during the Sagra of Sant'Antioco several times. Yet she never noticed that the yoke isn't the usual type that rests on the beasts' necks. Instead it links their horns. Our guide at the Museo Etnografico told us that this type of yoke exists only in Sardinia (ruled by Spain for four centuries), Spain and a few other countries which were also under Spanish rule. Where did it come from? There's a Nuragic bronze statuette from around 800 BC of exactly the same yoke. Perhaps it originated right here in Sardinia. The Tastes & Textiles: Woad & Wool tour followed Celebrating Sardinia. First we had a two-day workshop doing natural dyeing. First up, calendula. We heard about its many health benefits and also learned how to use the pigment from the petals as a dye. A Woad & Wood tour had to include woad. Woad was the blue dye before cheaper and easier-to-use indigo replaced it. We have to show you at least one of the beautiful silk squares we created. We enjoyed learning how to print with rust dye from Emanuele Francione. He uses hand-carved wooden blocks he inherited from his grandfather. Not to forget that many wild plants are good to eat as well as dye with. We couldn't get enough of this tart made by our hostess, Federica Crocetta. On the final day of this whirlwind month Erica welcomed her group at the first meal of the Tastes & Textiles: Wine to Dye For tour. She was in for a surprise. During Covid when tables had to be spaced out, Baldo Vino had decided to open a new osteria for the traditional cuisine and go 'cheffy' at the original restaurant Erica knew so well. Everything was well-cooked and delicious. But of course now Erica wants to go back to try the new place serving the old food! Review pending... June 'The most amazing thing about today was that I made a basket!' said Lydia, tired but happy at the end of another brilliant day on the Wine to Dye For tour. Erica wrote about the day: 'We went into the Padule (Marshes) di Fucecchio where Alessandra told us about the raw materials used for centuries to make baskets and other everyday articles. Then back to the Research Centre to learn to plait (braid) the marsh reeds. Simple enough, but we had to plait at least 5 metres and it was difficult to make it tight enough and to keep the diameter even along the whole length. After our picnic lunch, we went into the classroom to stitch the plaits into baskets. Despite our patient instructors, at first everyone said they couldn't do it. The stitching was so hard on our fingers. But slowly, slowly the plaits got stitched into place and everyone made a basket!' The food on tours is always divine and in June it was no different. There were lots of special meals on the Wine To Dye For tour. Dinner with a view at Da Delfina (Artimino), an elegant seafood dinner at Corradossi (Pistoia), lunch prepared by our olive oil expert at Villa Magia (Quarrata), dinner in a garden at Agriristorante Cocò (Lamporecchio) and a mega-steak at Rafanelli (Pistoia). The centrepiece of the tour is our two-day workshop with Tommaso Cecchi de' Rossi. Each person makes a handbag designed by Tommaso using leather and cloth they dye themselves. They think of a colour, and Tommaso helps them mix the dye, using wine as the basis. If you want to see how they came out, keep reading. We took some special photos on our repeat tour in September. Some of our guests had chosen to go straight on to Sardinia for our 5-day Tastes & Textiles: Sea Silk in Sardinia tour. The favourite day is always the workshop with Arianna Pintus, learning about bissus, a fine fibre from the beard of a mollusc, surrounded in mystery and myth. Arianna also leads us in a creative weaving workshop. July July was all about bread on our brand new Artisan Bread Course Tuscany. A glorious week working with five very different bakers. The first baker we met is Stefano Bechelli (pictured) who runs a family bakery called Pane del Gonzo. He makes his bread pretty much single handedly with the use of modern technology. His flour comes from Tuscany. Next up was Damiano Donati a talented chef who taught all there is to know about sourdough bread. Of course a lunch prepared by the man himself couldn't be passed up. Erica scours remote mountains and valleys for unique products for her courses. Crisciolette are found only at the village of Cascio in the Garfagnana. Alessandro Bertolini and his team taught us to make this tasty wheat flour and cornmeal griddle bread, flavoured with pancetta or wrapped around cheese. Another dream came true on this day. Dana wanted to go up to the top of the bell tower. Alessandro just happened to have the key... The obligatory 'look what we made' photo featuring delicious Garfagnana potato bread which was baked in the wood-fired oven of Paolo Magazzini. July also brought the launch of the new standalone sourdough panettone course. It's run by a familiar face, Mirko Tognetti, who teaches our gelato courses. Three chefs from India were the first to take the course. It's a very technical course but Mirko makes it seem easy, and our participants were delighted with their finished panettone! By popular demand we also launched a short sourdough pizza course with Neapolitan pizzaiolo Onorato Salvatore at his Pizzeria MaryFrank in Lucca. You can take it as a two-day stand-alone or add one or two days with Onorato onto any of our other courses. As you can tell from this blog, Erica has been so busy running courses and tours, she hasn't had time to put the course on our website. Subito! which should mean soon, but as used by Italian plumbers, means maybe sometime later this month—or next. August We kicked August off with an Art & Science of Gelato course. Day 5 is when our students get to create their own flavours. Arjun chose Kesar Badham, a popular milk, almond and saffron drink in his home country of India. Sublime! Sometimes one day in a tour isn't quite perfect. Erica managed to squeeze in a research trip to fix it. It was on the Wine to Dye For tour. Naturally we had to taste wine as well as dyeing with it. The morning had started perfectly in the vineyards and tasting room of Fattoria di Bacchereto. The weakness was the time machine in the afternoon that didn't quite make it back to the Etruscan period and, although the view from the restaurant was magnificent, the cooking had become a bit pedestrian now that mamma had retired from the kitchen. The Tumulus of Montifortini vividly displays the impressive building skills of the Etruscans. Time machine reset. And at the Osteria dei Mercanti in Carignano, she found mamma still in the kitchen. Day solved. We welcomed our first students from Puerto Rico on the Art & Science of Gelato course in mid-August. Naturally they had to make Piña Colada gelato. Yum! We were delighted to have some of our students from previous courses come back for the Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course in the Garfagnana. Parmigiano is produced just over the Apennine Mountains from the Garfagnana and several participants took advantage of the short hop over there to see how they do it. September Another wonderful Tastes & Textiles: Wine to Dye for tour took place in September. Our tours are based in the countryside, but we couldn't miss out the Lisio Foundation in Florence, where we see their artisans in action weaving silk velvets and brocade. Our other destination in Florence was the Scuola di Cuoio (Leather School) at Santa Croce. We learned how to tell the difference between real and faked leather of different animals. All their leather comes from certified sustainable farms. Copper pots are a dream to cook in, but they require maintenance. We got to watch the process at Antichi Mestieri (Ancient Crafts) where top restaurants send their pots and pans to be refurbished. Then it was off to Sant'Antioco again for Tastes & Textiles: Sea Silk in Sardinia where we were trying a new hotel right on the lagoon. Perfect! This is where we'll stay for Celebrating Sardinia in April 2023. One of the highlights is the costume workshop where we can feel the fabric and see the beautiful embroidery and needlework up close. We decided that a 3500-year-old megalithic tower was the perfect setting to capture the elegance of the bags we had made with Tommaso Cecchi de' Rossi on the Wine to Dye For tour! October Fanfare please for the debut of our new aprons at the final Art & Science of Gelato course of the year. They may not be as cheerful as our old ones, but I know for sure they're not made by slave labour, and the cloth is so nice to touch. They're designed and produced specially for us by Busatti of Anghiari, where we have a private tour during the Woad & Wool tour. In a little break from longer tours and courses Erica took a family to pick olives and taste oil at Agriturismo Alle Camelie. The last day of October saw Erica back on the train to Salerno Province for another Mozzarella & its Cousins course. It confirmed we were right to base the course totally in Salerno. The other great improvement is that the last two days of the course take place during production runs at Prime Querce. No need now to stay an extra two days to witness the production. November The winter months brought the Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany and students from all over the world. In November we welcomed guests from Finland, the Netherlands, USA, France and Romania. December What better way to end the year than with a nose full of white truffle? Here are two happy guests snuffing the truffle they uncovered on the new Truffle Course. Can you imagine anything better?

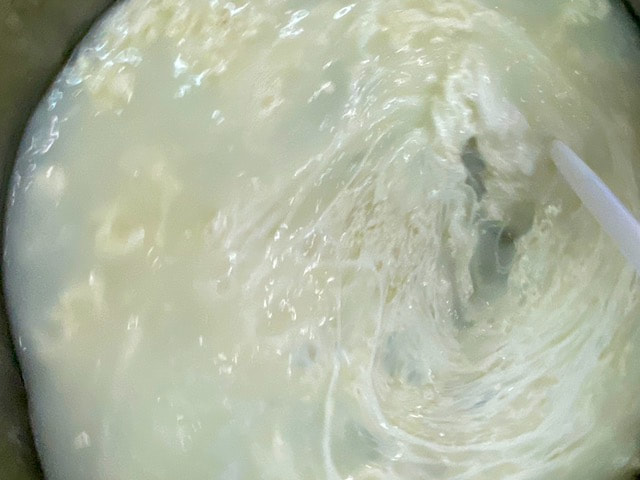

I hope you've enjoyed this mega run down of our 2022 tours and courses. We'd love to see you in 2023. Browse the website to find out what's on offer and don't hesitate to contact Erica with any questions. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. Guest blog by Adam S. Thompson, Head Cheesemaker & Partner at OroBianco Italian Creamery (Texas, USA) I've waited a long time to learn the art of pasta filata. After 15 years of making "mozzarella" or something in that genre, I can finally say I actually know how to make traditional pasta filata cheeses, using water buffalo milk, as it was intended to be produced. My name is Adam S. Thompson, and I'm the head cheesemaker and partner at OroBianco Italian Creamery — the one and only water buffalo dairy and creamery in Texas. I've been making cheese for over 15 years, with my first one being a quick method mozzarella, using citric acid and store bought milk. Before the buffalo, I had a goat dairy and made an array of cheeses and yogurts from their milk. I've also made sheep and cow milk cheeses at a couple of other operations, and trained in Mexico City on Oaxaca cheese — a pasta filata cheese, but made in a completely different fashion. I joined the team at OroBianco in September of 2021, however, I had been doing some testing of the milk as early as March of 2021. For the past year, I've made a couple of decent products that somewhat resemble mozzarella, but never could get the texture and flavor of what we really wanted — an authentic buffalo mozzarella, that oozes the milky water out when you bite into it. Made and served fresh and meant to be eaten almost immediately. While Covid restrictions were preventing me from taking this course, Erica Jarman of Sapori & Saperi helped me as much as possible from afar, even getting a Zoom class going with the former head cheesemaker at Prime Querce farm and dairy. She had also been telling me that I needed to see the process and experience it firsthand to really understand it. I’ve attempted the mozzarella at least 50 times over the last year, sometimes pushing into the morning sunrise, trying to accomplish this cheese making process. Time and time again, I would get a nice cheese, but not the mozzarella we were aiming for. Finally, in October 2022, I arrived in Campania, Italy, to take the course. The class was the most educational course I’ve ever received in such a short amount of time. I think it helped I had been trying and failing, as I had many questions to be answered and walls to get over. Any time I had a question, no matter how small or off-topic to the current stage, Erica would wait for the cheesemaker to finish what he was talking about, and field my questions to him. We trained at two different dairies, Chirico and Prime Querce. Each place had its own methods and variations for the different pasta filata cheeses, but the basics were more or less the same. The cheese making facilities were full of passionate people, who would move like ants at times, in a synchronized, and super-speed fashion at times. I was allowed to make a complete batch at one facility, then work on all of the different stages at another, in the midst of normal production. I had no question left unanswered after this course. The mozzarella and pasta filata training here was incredible, but there was much more to this course. We also had the pleasure of being accompanied by a very talented sommelier, and did nightly wine tasting, and went to dine at some of the finest establishments I’ve ever eaten at. Some were embellished with gold trim and crystals, serving high-grade steaks, and some were little hidden gems, with the morning’s fresh catch served in unique presentations. We even had a “dinner with friends” where one of the B and B owners invited some locals, and we dined family style in the living room. The entire course was very organized and maintained on a sometimes very strict schedule, and this ensured we were always where we needed to be to learn, and visit the extracurricular, planned activities. Everything was purposeful and useful to bring these skills back to Texas and incorporate into my cheesemaking, as well as bringing information about the water buffalo themselves back to the dairy. To anyone wanting to learn the art of pasta filata, this course is a must-take. You won’t call one of these places directly and get a class, and you won’t find these courses online, or marketed on some big cheese website. Most places are very secretive, or do not want to waste the time teaching other people how to make this classic cheese. The food alone is worth the cost of the course, in my opinion. Of course my focus was always on the cheese making, but the course being completely submerged in the culture, and getting to taste different foods, and wines, from around the terroir left me with an elevated sense of inspiration. The people there were very welcoming, and passionate about their trade. Not only have I finally locked down the mysteries of mozzarella, but found myself returning home and making my own tomato sauce, gnocchi, and other classic Italian dishes for my family. If you’re “stretching” mozzarella at home or for a dairy/cheesemaking facility, you’re likely doing it wrong. True mozzarella only takes the perfect curd, and almost boiling water, and it “spins” together almost effortlessly. The mozzarella should make you take a step back when biting, so the beautiful, milky whey doesn't get all over you. So break out the pocket-book, book this course, and get a class that will give you all the tools you need to make mozzarella, as well as fill you with inspiration and the Italian culture that makes this cheese what it is.

Sant’Antioco is a small island off the southwest coast of the large island of Sardinia, an island squared you might say. Sant’Antioco is afflicted by two winds: the maestrale from the northwest and the levante from the east. One or the other blows nearly every day, but since they take turns, there’s always a calm sea for fishermen on the leeward side of the island.

On a bright spring morning the fishing boats are tied up to the quay, squeezed in side by side. Too many fishermen chasing too few fish.

Many of them augment their income by offering pescaturismo, fishing excursions for tourists. I’m excited. For years I’ve wanted to learn about fishing in the Mediterranean, but it took a long time to find the right place and fisherman.

We arrive at our boat the ‘Alessandro P.’ and the live Alessandro, son of fisherman Mauro Pintus with whom we’re going fishing. Soon Mauro, his wife Roberta and their 14-year-old daughter arrive all lugging groceries. We climb aboard from the stern onto the working deck.

We proceed along a narrow corridor past the engine room and the galley and climb out onto the prow and onto the upper deck where lounge chairs await the non-fishermen in the group.

With Mauro at the helm we chug out into the lagoon to find the nets Mauro and Alessandro set last night. This must be travel at its slowest, apart from crawling. The distance we covered by mini-van in five minutes takes at least thirty in the boat. I thought it might be boring, but at this speed there’s an infinite variety of detail to observe: birds overhead, features on the shore and especially the changing colour of the sea.

After a while we stop seemingly at a random spot in the sea, and the action begins on the working deck. We’ve reached one end of Mauro’s net which he laid the night before. He marks the end by tying an empty plastic container to it which floats on the surface of the sea. Now we learn what the strange wheel on the port side of the boat is for.

The net isn’t anything like I’d imagined. I guess I’d been thinking about illustrations in children’s books of a large square net that gets filled with fish and you pull it up from the four corners. Instead this is a very long, narrow net, about a metre in width and a kilometre long with a thick rope running along each side.

At first there aren’t any fish. Then a couple of sea cucumbers. Not edible, says Mauro. He uses them as bait.

I feel sorry for this creature, but I’m also a carnivore and am sure our ecosystem wouldn’t work if we all lived as herbivores at the bottom of the food chain with no one at the top eating meat. But I also want to be aware of what is being killed and how.

Mauro invites us to help take the fish from the net as he continues to reel it in.

Even though we follow Mauro’s instructions to extract the fish head first, it’s not easy. If lunch relied on us, we might starve.

Finally we come to the end of the net which is piled in a heap on the working deck. Mauro joins us at the task of untangling fish from the net. We soon tire and go look at the scenery from the upper deck.

Good smells waft up from the galley.

When we’re called to lunch, we find the working deck transformed into a cheerful dining room.

I ask Mauro about tuna. We all believe that tuna is fished out. I’ve been avoiding eating tuna for several years, but will have to be polite. Mauro states that there are too many tuna. That’s why the catch is so small. Tuna are at the top of the food chain, and if there are too many, like the wolves eating my shepherd friends’ lambs, they decimate the populations of smaller fish. So why are we always hearing that there are no tuna left? He says it’s mainly due to the politics of fishing. Who’s allowed to fish where and how much. He presents it as a war between fishermen and politicians with marine scientists and environmentalists somewhere in between. Clearly some more research is in order.

He and Roberta and two other fisher families have formed a cooperative to bottle tuna and two fish salads, octopus and mixed seafood. The men fish and the wives work in the bottling plant which we visit when we’re back in Sant’Antioco.

Whatever the truth about tuna, this is the best tuna salad I’ve ever eaten

The zuppetta is a rich tomatoey fish broth ladled over toasted bread.

By now we were struggling, but the fried fish is light and not at all greasy. A joy to eat. But this isn’t the end after all.

Mauro disappears for a moment and returns with his guitar. We hadn’t been expecting entertainment. It turns out Neil Young is one of his favourites, and he’s delighted that Claudia knows a few songs.

We won’t win the Eurovision Song Contest, but it’s a lot of fun.

If you'd like to go fishing with Mauro and indulge in Roberta's stunning lunch, there are still a couple of places left on our Celebrating Sardinia tour from 21 to 30 April 2023.

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here.

If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 21 May 2017.

Guest post by Dana Roberts

The brand new Artisan Bread Course Tuscany ran in July and we enjoyed showing our guests what our artisans have to offer. Dana Roberts joined us on the course and has allowed us to share her colourful experiences and wonderful photos with you here. Here's what she had to say... So far, my bread course has been amazing! We started at a family run restaurant with amazing homemade pasta. Then we went to a commercial bakery, where we watched them bake a massive batch of bread from beginning to end, finishing at 1 am.

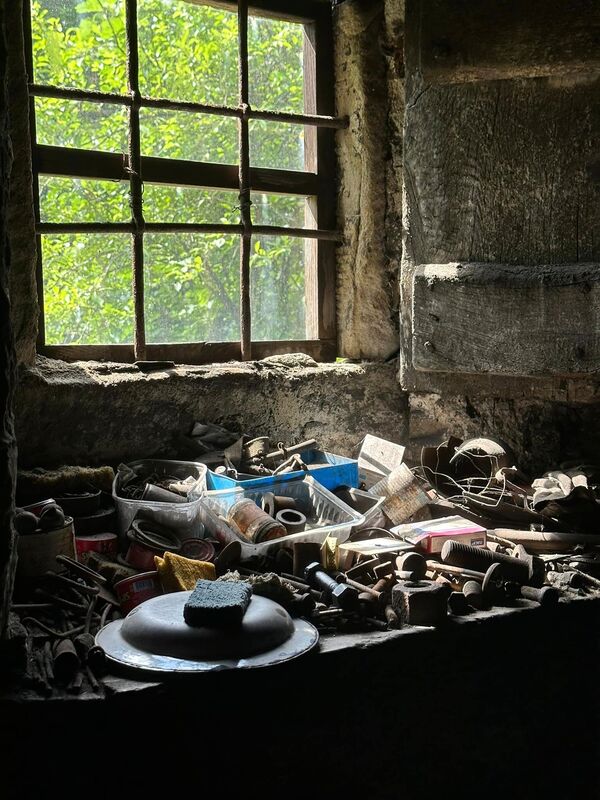

Then on Monday morning, we visited the last remaining traditional blacksmith. He is totally off the grid, using the power of the stream that runs under his forge to power his tools. He showed us how he would forge the griddle pans used to make griddle bread. It was quite the experience!

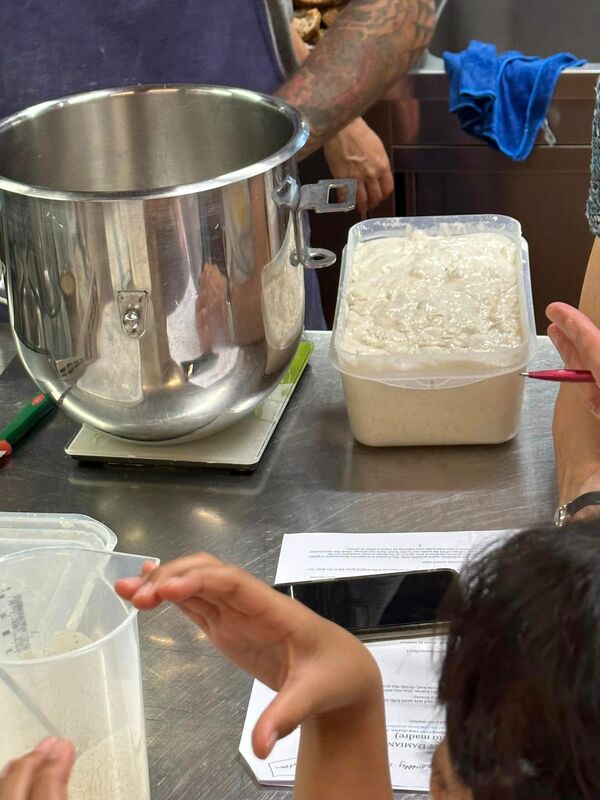

Then off to Fattoria Sardi, a biodynamic farm and winery, to learn about sourdough. Biodynamic farms focus on creating a soil which will remain vital and productive for years to come. It’s kind of like the next progression for organic farms, which focus on creating healthier products for the consumer. Biodynamic farms are just starting at the source to create the desired outcome for future generations.

All of these classes are interspersed with amazing food and drink. As much as possible, everything is locally sourced and sustainably farmed. A lot of small businesses trying their best to stay afloat and create a better world at the same time.

We started out on Tuesday at Fattoria Sardi to cook the sourdough we started on Monday.

During one of the wait times (there’s a lot of waiting involved in making bread), we toured the vineyard and learned more about the biodynamic system. We had another amazing lunch here (I highly recommend it if you’re ever in the area), and got to bring home our bread.

Remember those griddles we saw being made at the forge on Monday morning? They are called ‘testi’, and we learned how to use them on Wednesday. We started out by making fogaccia leva (no, that’s not a typo). We added pancetta to some, cheese to others, and they were all delicious. We also learned to make a traditional Tuscan bean and sausage dish called fagioli all'ucceletto.

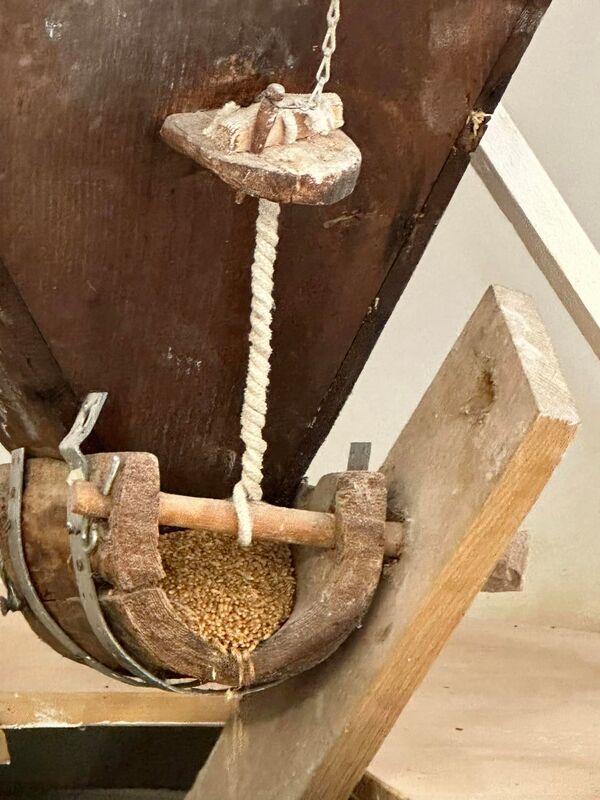

From here we visited a functioning water mill from 1736, which I found very interesting. Then it was off to Cascio, which claims to be the only place that makes crisciolette, which also uses the testi. This time the pancetta was cooked into the flatbread, which was also delicious. We also made necci, which uses chestnut flour.

At the end of the class, I asked if the tower in the town would be open during their upcoming ‘festa’. Turns out, the guy I asked had the key and he let us go up right then! I loved it!

We finished off the night by going over to Barga, checking out the duomo, and eating yet more food. I’m going to have to find more towers to climb just to work off the twenty pounds I’m going to gain this week!

This is Paolo Magazzini. He is carrying on his mother's baking. He is also a farro and beef farmer, and runs a farro mill.

I found it interesting that the bread is mixed just on the counter. The brighter yellow is riced potatoes, which is the type of bread his mother made for the village. The starter dough used in this bread is over fifty years old!

All the bread in this bakery is baked in a wood fired oven. The fire is built directly on the base until the oven is at the right temperature. Then the embers are removed, the dough put in, and the door put on while the bread bakes.

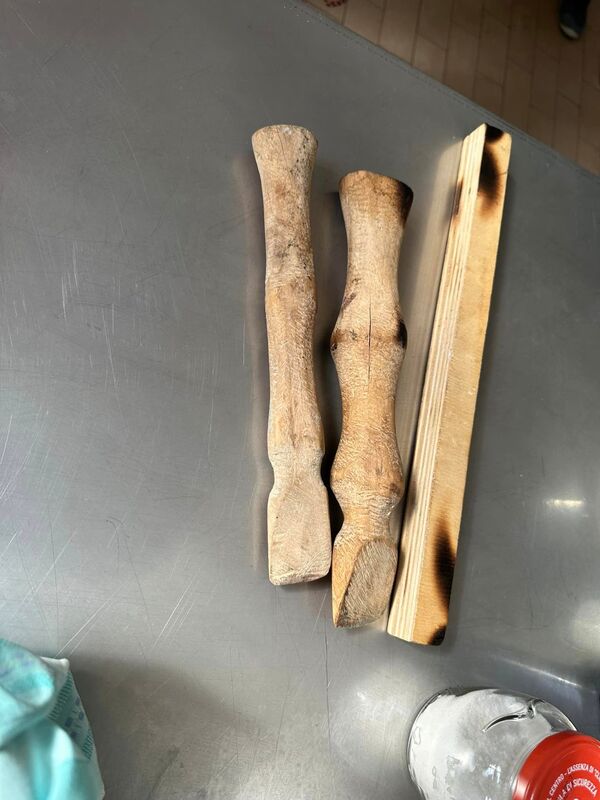

Our guide, Erica, showing us the boughs which are used to sweep the embers out of the oven before putting the dough in. Paolo is soaking the broom to prepare to sweep the oven out.

Getting the embers out quickly. It has to be fast so the oven doesn't cool down too much.

There was a small herd of beef cattle on the farm as well. One of the cows just had twins, which was a first for Paolo's cows.

Here is the finished product!

We then drove to this fort, overlooking the valley. We learned about how food was used in medieval times.

At the end of the evening, we went to a winery for another amazing meal. These are the grapes for their Pinot Nero wine. It's a small vineyard, producing only about 8000 bottles. I also really liked their white wine.

The inside of their cellar, which illustrates just how much smaller it is than most wineries I have toured.

Okay, the bread adventure is finished, and it was an incredible experience. I loved meeting local artisans, and learning about Italian traditions and customs. It is truly what I wanted when we decided to move to Italy. The tourist sites are very impressive, but you don't really get a feel for what life is like here, and you can't appreciate the culture until you get off the beaten path.

I also feel it is important to gain an awareness of how this culture is slowly dying out as people buy items based on convenience and price rather than quality. A huge thank you goes out to Sapori e Saperi Adventures for creating this experience, and to the clients who had to cancel due to Covid and gifted me with the opportunity to attend. I made some new friends, and hope I can remember all that I learned, both about bread and about Italian life. This is all part of the Artisan Bread Course Tuscany, which will be taking place again from 2-7 July, 2023! Find out more here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed