|

The Garfagnana is unquestionably beautiful. It’s rugged mountains cloaked with green forests set it apart from the Tuscany of Chianti to the south and the Po Plain of Emilia over the Apennine Mountains to the east. But I could never understand what use it could possibly have been to the Dukes of Ferrara, the Este family. In 1429 Nicolò d’Este annexed the Garfagnana to his realm and for almost four centuries the Garfagnana remained under the Dukes, who defended it against the republics of Lucca and Florence. I searched the internet; I asked my city guide in Ferrara. It seemed never to have occurred to anyone to wonder why. Today I went to the Sagra della Minestrella di Gallicano. Minestrella is a soup of wild herbs and beans made only in Gallicano, a town of fewer than 4,000 people. Today it is the southernmost town in the Garfagnana. When the Garfagnana was under the rule of the Dukes of Este, Gallicano was the northernmost Lucchese stronghold (apart from the even smaller town of Castiglione di Garfagnana). Directly across the river in Barga the Florentines held sway. Surrounded by strong neighbours, Gallicano went its own culinary way. The plan of the day included an introduction to wild edible herbs, a walk (in the rain — not planned) identifying the edible herbs along the path to the Antica Trattoria dell’Eremita (Old Restaurant of the Hermitage), where we not only feasted on the legendary minestrella, but numerous other traditional dishes illustrating the use of wild herbs, not omitting the focaccia leva, a flatbread unique to Gallicano. The conversation turned time and again to the detailed history of the region and the extent to which it influenced agriculture and culinary tradition. Everyone seemed to be well versed in the history of the place. It was the symbolic and often the actual basis of their ownership of the land. I talked to Cesare, who had organised the event, about taking my clients to forage for edible herbs and use them to prepare a meal. He was agreeable, but cautioned that the activity wasn’t to be just about the identification of the plants, their recipes and flavours; it had to include their cultural history, what they meant to the families who ate them. Ivo Poli, who had given the lecture on the wild plants, gave me a lift back to my car. He lives in the next town north of Gallicano and had always been a Garfagnino (citizen of the Garfagnana). I asked him the question that had teased me for so long. It’s easy, he said, ‘We had the petroleum of the Renaissance: charcoal.’ I’d walked in the tree-covered mountains; I’d seen a charcoal burner at work; I’d watched the blacksmith Carlo Galgani beating iron in his charcoal fire; I’d been to a village that produced nothing but nails; but I’d lacked the historical glue to put them together. Far more important than nails and horseshoes, every ruler needed charcoal to smelt iron to make arms to defend his borders and subdue new territories. The village streets lined with grand houses with imposing doorways suddenly make sense as residences of the oil barons of their day.

0 Comments

Pasqua is Italian for Easter. Last year I went to Francesca Bonagurelli’s agriturismo Al Benefizio to join her family and friends for their typical Easter lunch. Queen of the day Francesca at the right edge of the photo nearest the kitchen, her daughter, her nephew, her cousin from Milan, her brother-in-law, her sister, her mother and her dear friend Marta. An antipasto consisting of the usual crostini and some olives didn’t prepare me for the surprises to come. The primo was something I’d never had before: gnocchi alla romana. Instead of the little potato cylinders, these circular cakes were made of semolino polenta to which egg yolks and parmigiano was added. And instead of boiling them, they were sprinkled with butter and more parmigiano and browned in the oven. Delicious! The secondo, roast beef, was accompanied by enough vegetables to please any of my clients, who are always asking, ‘Where are the vegetables?’ Here again there was a surprise: a vegetable looking like the hair of a punk angel who had dyed it bright green. It was Salsola soda, a saltwort that grows around Mediterranean coasts and is harvested between March and May. In Italian it’s called agretti or barba dei frati(monk’s beard—a punk monk?). Wikipedia tells me that it was important historically as a source of soda ash, one of the alkalis needed for soap and glass making. The clarity of cristalloglass from Murano depended upon soda ash. As a food it’s supposed to have a detoxifying effect. Just when we thought we would burst, the table was cleared, the cakes arrived and the spumante was uncorked. Naturally there was a colomba di Pasqua (Easter dove), a traditional Easter cake similar to panettone served at Christmas. Recently arrived from Naples was another novelty: the pastiera napoletana wrapped in its Easter finery. One legend reveals its origin. One night some fishermen’s wives left baskets of ricotta, candied fruit, wheat, eggs and orange flowers on the beach as an offering to the sea, so it would protect their husbands and bring them back safe and sound. The next morning, when they descended to the beach to greet their returning husbands, they discovered that the waves had mixed the ingredients, and in the baskets was a cake.

I feel vaguely uncomfortable every time I hear the phrases ‘healthy eating’ and ‘balanced diet’. It’s not that I disapprove of eating healthily or balancing my diet, it’s just that I’m not sure we can ever know what these terms mean. A recent article in The Guardian newspaper by Joanna Blythman highlighted the problem. Click here to read the whole article. It’s worth browsing a sample of the 1,374 comments too. What tempted me to add my voice to the throng is that I think there’s something much more fundamental wrong with what we’re told. I once took part in a UK medical research project aimed at discovering links between diet and women’s health. Every so often they asked me to fill in an online form giving details about what I’d eaten the day before. The designers of the project and the form clearly didn’t have me in mind. For example, in the section asking how many slices of bread I ate, they asked whether it was white or wholemeal, but there was nowhere to say I’d baked it myself using stoneground, organic wholewheat flour I’d bought from the miller. Nor to state it didn’t contain any flour improvers and was made by a long-rise sourdough method. Although I believe it’s healthier than mass-produced bread, do I know for sure? No, and this study wasn’t going to reveal the answer. Another major problem with all dietary research based on surveys is that people lie. Do you want the researchers, or even yourself, to know that you ate three Kit Kats and drank a whole bottle of wine yesterday? And what about the problem of the long-term effects of particular substances? In the laboratory biologists can test the effect on animals of chemicals occurring in food, either naturally or as additives during cultivation or processing. But as far as I know it’s difficult, maybe impossible, to test the effect of ingesting that substance for 20 or 50 years.

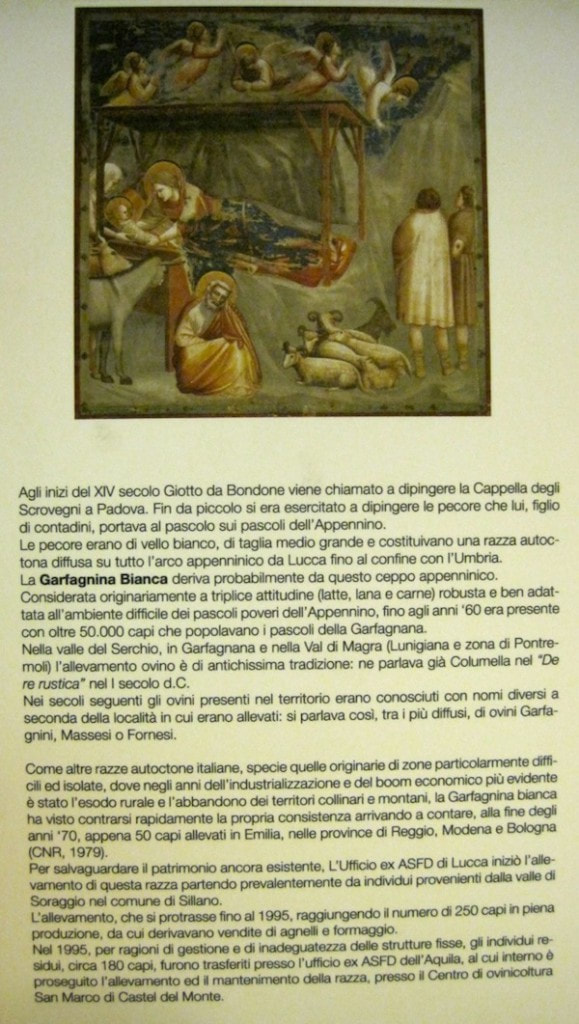

The last of my doubts about dietary advice stems from genetics. We’re all different. One person might live to 100 eating nothing but red meat and fat, whereas another dies of a heart attack at the age of 52. Was it their diet or their DNA? Many years ago when asked on her 120th birthday to what she attributed her longevity, the oldest woman in France replied it was giving up smoking when she was 118. On my tours you eat unprocessed food, much of it straight from the artisan producer. In my opinion it tastes much better than industrial food, but I can’t claim it makes you healthy. Next chance to taste for yourself is the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June (http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/component/content/article/2-small-group-tours/56-cheese-bread-a-honey). At noon on Wednesday 9 April in Florence, Dr Francesca Camilli of the Italian National Research Council will present a paper to the 1st European UNESCO-SCBD* Conference on ‘Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe’. Her paper is entitled: ‘The Garfagnana Model: exploitation of agricultural and cultural biodiversity for sustainable local development’. One of her prime examples will be Cerasa farm, a mountain paradise which is no secret to my clients who have written rapturously about their visits (here, here, here, and here May 2012). Mario, Gemma and their daughter Ombretta are a fundamental part of a project, overseen by the Germplasm Bank set up by the Comunità Montagna della Garfagnana (now the Unione dei Comuni), to preserve the indigenous Garfagnina Bianca sheep. If you’ve noticed some sheep lurking in the foreground of a nativity scene by Giotto, it could have been this breed, which was once common in the Apennine Mountains. Mario and the dogs look after the sheep. Gemma makes pecorino cheese and ricotta from their milk. Ombretta dyes their wool with natural dyes and has them knitted and woven into saleable products. Mario rears rams to sell to other farmers who want to join him in preserving the breed. Another strand of the Germplasm Bank project is the botanical station at Camporgiano. They have rescued dozens of indigenous varieties of fruit and vegetables. Besides being grown at the station, each variety has been entrusted to a custodian, a local farmer responsible for its propagation and preservation. I visited the station last year where the Director Dr Fabiana Fiorani explained their work. In 2013 the Garfagnana submitted several apple varieties to the European Pomological Exhibition at Limoges where it gained the distinction of ‘Custodian of Biodiversity’. Watch this space for the announcement that I can take you to the botanical station followed by a visit to one of the custodians and lunch in their home. The next opportunity to visit Cerasa is during the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June. The UNESCO conference lasts for three days, during which dozens of international experts deliver research papers. It could be a big yawn, but judging by some of the titles, I for one would be awake. For example, a paper by J. J. Boersma of Leiden University is intriguingly titled ‘Could the rewilding of Europe be seen as progress?’, with the implication that the answer is ‘yes’. To me the most interesting theme is that biodiversity of domesticated plants and animals appears closely connected to cultural diversity arising from the traditions and identity of a place. Finding the balance between tradition and modernity may be the virtuous path to sustainable rural development. The mere fact of an international conference organised by UNESCO on the topic of biodiversity and sustainable development raises hope that the planet will not be entirely subjugated to the interests of agri-business. A more local, but equally important action took place yesterday, also in Florence, when Slow Food organised a demonstration against the introduction of GM corn in Italy. Fingers crossed! Find out more: Joint Programme Between UNESCO and CBD, Convention on Biological Diversity, Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe Conference programme, Les Croqueurs de Pomme

*Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, based in Montreal, Canada |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed