|

This week I got into a Fiat Panda 4×4 that turned out to be a time machine. The precise date to which it took me was 1969, but it could easily have been a couple of centuries earlier. Renato, the butcher and shopkeeper of my village Casabasciana, wanted to take me somewhere hidden. He knows I like walking in the wilderness, and thought this place would appeal to me, but wouldn’t reveal any more. We fixed Thursday afternoon, and I gathered my equally curious and appreciative friends Lone, Klaus and Tove to accompany us. Crammed into the Panda, we drove down the hill to the Lima Valley and turned right toward Abetone and Renato’s home town of Popiglio. Opposite the road to Lucchio, before Popiglio, we turned left into a gravel lane where Renato’s cousin Giuliano was waiting for us with his Panda 4×4. We divided ourselves between the two cars and bounced and wound up the eroded track, passing an occasional farm building. Just when it seemed we couldn’t go any higher, we reached the end of the road and the farmstead where Renato’s and Giuliano’s mothers and Giuliano himself were born. The sky was a uniform grey that day which added to the mood of desolation. The buildings sat on a narrow terrace, with stalls and pigsty beneath the house on the downhill side and the main door at the back. Numbers 1 and 2 must have been the buildings we passed on the way up. Giuliano opens the main door and to our right is the kitchen, focal point of a farmhouse. There are almost too many things to take in, objects signifying a different way of living. The family tries to keep the place in good repair, but it’s becoming more and more difficult. I’ve seen these burners in many old houses. You put coals from the hearth in the iron boxes and a trivet on top on which to rest the pot. The bottoms of the boxes are gratings that allow the ash to drop through and you remove it through the square holes beneath. The bedrooms are on the upper floor. Renato explains that this object was made from thin strips of chestnut wood. You hung a pot of hot coals on the hook inside at the apex and placed it under the covers as a bed warmer. We all giggle at the idea of a priest in the bed. In the background another model of ‘priest’, and in the foreground a tool to hold a skein of yarn while you wound it into a ball. The upstairs landing, like the kitchen, was another ethnographic museum. Giuliano’s father and grandfather were charcoal burners. There was a mountain cable car for hauling heavy goods up to the house. The tour of the main house concluded, we went to see the rest of the buildings. At the far end of the courtyard the door on the right opened into the much smaller house where Renato’s mother was born. Renato asked if we could guess why they left the courtyard covered with weeds. Because the pavement was so beautiful that if anyone saw it, they’d be up there with crow bars in an instant. The metato was the building in which chestnuts were put (‘mettere’ means ‘to put’) to dry on a slatted ceiling above a smouldering fire before being shelled, sorted and taken to the miller to be ground into flour. Back in the house we had seen some of the other tools required for the later stages. When the earthquake of 1920 caused landslides that covered several villages, the lower walls of houses were reinforced with these stone buttresses, just like a mediaeval fort, one of which we could just see across the Lima valley. Above the tiny village clinging onto the wooded slope are the remains of a fortress, part of Lucca’s late mediaeval line of defence against the Florentines. There was an almost unwelcome surprise. Adjoining the far end of the house was another house, owned by other people from Popiglio. They had brought it right up to date, including a television aerial. I wanted to see where the charcoal pile used to be. We drove back down the road a few hundred metres where we were greeted by more spectacular views. We know Vico Pancellorum well because of its restaurant Buca di Baldabò, one of our favourites in the area. On the spot where the charcoal used to be produced was a strange orchid. It has no chlorophyll, but is a saprophyte which feeds on rotting vegetation with the help of a symbiotic fungus.

As we drove away, we learned the sad subtext to the visit. The family had concluded they had to sell the house. Their children have no interest in it, and since Prime Minister Monti introduced more taxes for uninhabited buildings, it was becoming too much of a financial drain. Their 7 hectares (14 acres) of fields and woodland are also subject to taxes. The top half of the road is private and requires constant maintenance. But who would buy it? Do I know anyone?

0 Comments

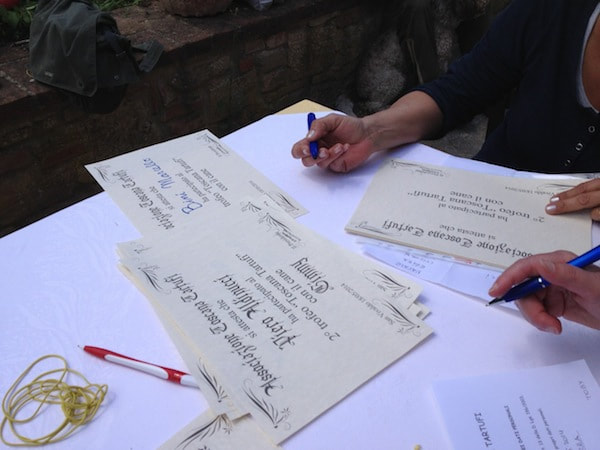

I’m just back from the second annual Tuscan truffle hound competition organised by Riccardo, my truffle hunter. The competition is about as exciting as a village cricket match without the beer tent. Very little happens, but it does have the merit of being easy to understand the rules, unlike cricket (at least for me). I used to listen occasionally to a cricket match on the radio enjoying the foreign language of the commentators. Truffle hunters also have their own language which seems to consist of one- or two-syllable utterances to which the dogs rarely listen. This video gives you some idea of the pace and mutterings. [vimeo]https://vimeo.com/95670529[/vimeo] If it’s not much of a spectator sport, at least it demonstrates the method used and patience needed to train a dog to be a good truffle hound. There are very few breeds that can’t excel, but you have to start the training when they’re just a few weeks old. Give them simple commands, teach them to retrieve a stick and eventually bury a plastic capsule with a fragment of truffle in it for the puppy to find—over and over and over again. Riccardo explains the psychology of training: dogs are pack animals and the man (I haven’t met a female truffle hunter yet) has to play the role of leader of the pack. Some men don’t have it in them. Others have figured out how to motivate their dogs to keep their noses to the ground. Riccardo and Teo demonstrate best form. Note his subtle hand movements. While not exactly electrifying, the location is beautiful and the camaraderie enjoyable. What better way to spend a sunny Sunday than chatting to friends while sitting on a stone wall in the shade of a pergola at San Vivaldo monastery. When the trials are finished, all the dogs and owners converge on the ring to retrieve the buried capsules. At this point a Franciscan friar emerges and surveys the scene. He gazes at the small square marked out on the lawn, shakes his head and states that surely in so small a space every dog would find every truffle. Meanwhile, the certificates are being prepared and the prize-giving begins. In 15th place, the man whose dog found none. No one’s a loser. In first place, a man no one knows. He wants to be notified of the next contest, but doesn’t understand what an email address is. What sets a Tuscan truffle hound competition apart from a cricket match is lunch. We drift into Il Focolare (‘the hearth’), a restaurant in the cellars of one wing of the monastery, for an abundant and well-cooked lunch. Riccardo and I have taken many guests on real truffle hunts (no plastic capsules) followed by a truffle lunch at Riccardo’s home (click November, but you can hunt truffles in almost any month). We’ve also designed an intensive truffle course, and soon we’ll have a truffle weekend on offer as well. Let me know if you’d like to be notified when it’s ready: [email protected].

After a full Italian lunch, I crave something fresh, light and pure. I stop at Patrizia’s fruttivendola in Villa (Bagni di Lucca) and buy a sack of new season peas in the pod. I love popping open the pods and detaching the peas with one swipe of my thumb. It can be a social activity too; children really get into it. I can’t resist popping a few raw ones into my mouth as I work. They’re so tender and sweet. One minute in boiling salted water and my dinner is ready. No butter, no ham, no spring onions, just a plate of peas. They melt in my mouth. You don’t have to have lofty ideals of saving the planet to eat locally and seasonally. You can do it as a totally selfish act to pamper yourself. To me it’s better than a massage.

The 2014 Slow Food guide to the extra-virgin olive oils of Italy is out. Since the 2013 harvest 130 Slow Food collaborators have been working hard to assess more than 700 farms and over 1000 different oils. Like wine, some vintages of olive oil are better than others: 2012 was a great year for Lucca oil, but 2013 was particularly difficult, producing less characterful oils. Nevertheless, the guide recommends nine oils from Lucca Province. To read more about olives and olive oil, please go to my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/extra-virgin-lucca/

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed