|

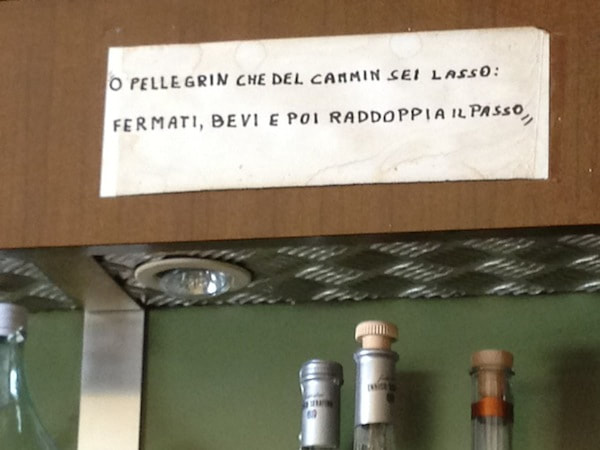

A couple of Thursday evenings ago I wrote a to-do list for Friday. The first item on the list was to pick up some leaflets at Topo Gigio, the bar-trattoria in Fabbriche di Casabasciana, the village at the bottom of my hill. The leaflets advertised a concert on Sunday for the benefit of the centre for the elderly at Casabasciana, which I was helping to organise. Considering the length of my list, all the things I wanted to get done before the weekend, the sensible thing would have been to hop in my car and drive the 3.8 km (2.4 mi). But it was a warm, not too hot, sunny day, and I hadn’t walked the mulattiera in ages. People in the village used to walk down it to school or work and back up again at lunch time every day. It seemed a bit feeble not to do it. I strapped my pennato lucchese, a Lucca-style billhook, around my waist and invited my friend Penny to accompany me with her secateurs. Mulattiera translates as ‘mule track’, but this makes it sound a paltry dirt path. In fact, the mulattiere (plural) were the super highways of the past, often many metres wide, surfaced in rounded cobbles or flat paving slabs, with stone-lined drainage channels at the sides or down the centre. Where necessary they were stepped. In mountainous areas like mine, they ran along ridges, usually just below the crest. Although they frequently crossed streams and small rivers, it was at the top where the water course was narrow and presented no great obstacle even in the rainy season. They descended to the valleys of major rivers only where absolutely necessary to arrive at a destination on the other side of the river. I’m not sure how old the roads in the Garfagnana are. It’s known that the Roman Consul M Claudio Marcello had the Via Claudia or Clodia Nova built in the 2nd century AD, and it’s likely that it followed an Etruscan road and possibly even earlier routes. The mulattiera that links Casabasciana with the valley is said to be mediaeval, but that’s the date people always attach to anything old. It’s about 4 metres wide and forms the main street in the village, descends about 100 m below the village and splits in two, the left fork diving steeply down to the pieve, the old romanesque parish church, and then continues to Sala, a hamlet of about 15 houses, which is linked by another mulattiera to the Liegora River which runs into the Lima River to the right. The other branch carries on straight down to the Lima, along which Fabbriche di Casabasciana is strung out. I’ve learned from my neighbours that upkeep of the mulattiera was the responsibility of each family through whose property it passed. In the ’60s the present-day car road was built, and since then the mulattiera has been used less and less by the locals. Only the sections used by woodsmen, hunters of wild mushrooms and wild boar, and horse riders (mostly tourists) are now maintained, and even these denizens of the forest tend to favour newer dirt roads suitable for 4×4 vehicles. It’s to us stranieri, who arrive with the notion of nature as a setting for recreation instead of work, that the task of cleaning the mulattiere now falls. Penny and I set off at about 9.30. We hacked, slashed and clipped our way to the bottom by around noon. Some parts of the road had been cleared but others were thick with elder and acacia saplings intertwined with clematis (old man’s beard) and brambles. It was particularly galling to find that one household had cut their land down to within a metre of the mulattiera and hadn’t been civic-minded enough to cut that stretch of the mulattiera as well. At Topo Gigio, arms scratched and bleeding, we bragged about our feat to the men playing cards or arriving for lunch, and taunted them by asking where they had been when needed. ‘O pilgrim, weary of your journey: stop, drink and then redouble your pace.’ Restored by the excellent worker’s lunch, I collected the leaflets and we set off back up the mulattiera. Even though uphill, it was much easier going this time.

If anyone knows of a volunteer work group skilled at repairing cobbled roads, please get in touch with me at [email protected]. They’ll receive warm hospitality at Casabasciana.

0 Comments

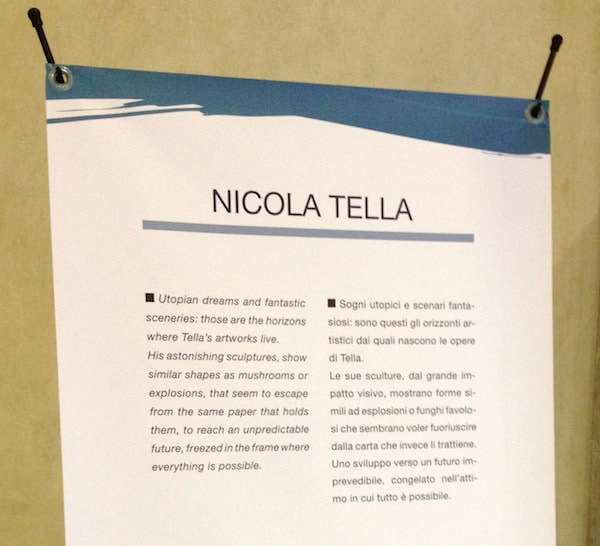

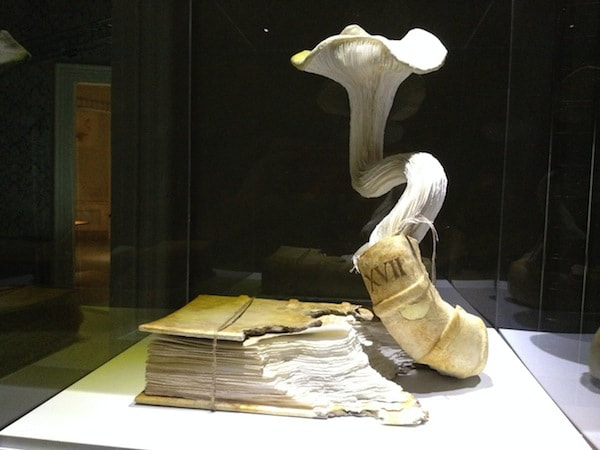

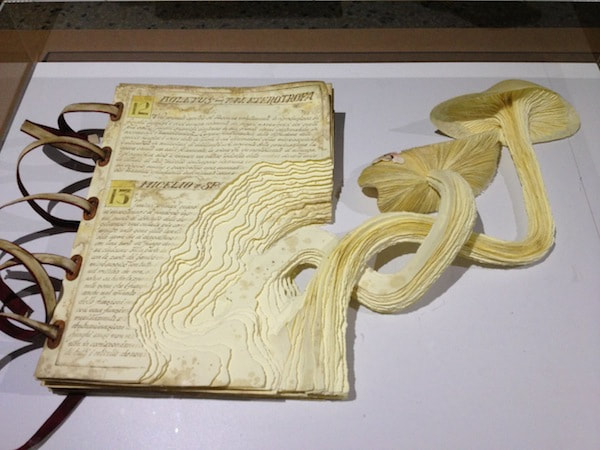

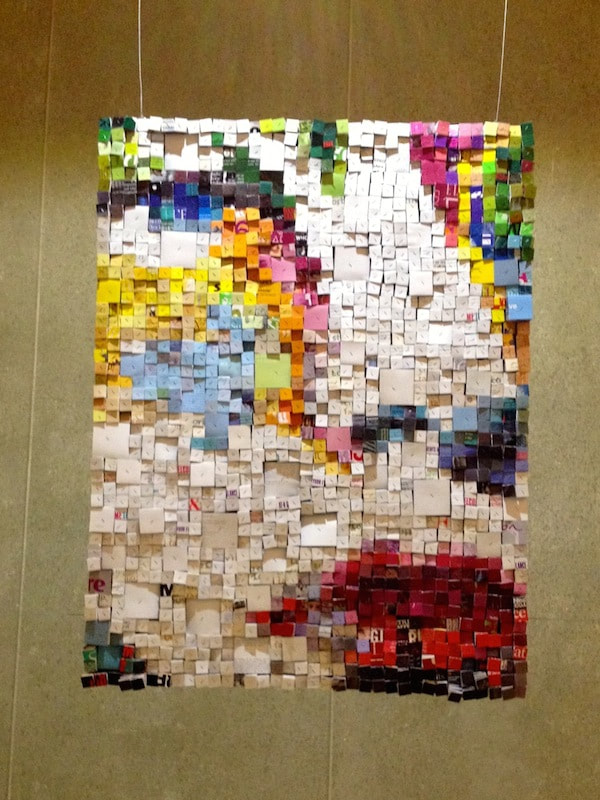

I know summer is here when I walk around Lucca in July and am confronted by larger-than-life paper sculptures: a phantom forest in Piazza San Frediano (1), a mythological armoured horse (2) under the loggia of the Palazzo Pretoria on the corner of Piazza San Michele, a surrealist right-side-up pear that morphs into an upside-down head up on the walls. The rules of the biennial international paper festival stipulate that all the materials used by the artists must be recycled. Sustainable environmental issues underly the themes of each festival. This suits Lucca. The province produces 80 per cent of Italy’s household paper (including Lu-paper) and 40% of its packaging and corrugated cardboard; and it’s Italy’s number one exporter of paper. Old, mostly derelict paper mills ornament many small valleys. Nowadays the main Serchio River Valley is lined with ugly modern mills which I used to consider a blot on the landscape. They became bearable, even desirable, when I realised that they’re major providers of employment in the valley, and serve to keep families together and stem depopulation of rural villages. This year I noticed an indoor exhibition entitled ‘Identità Liquide’ at Real Collegio, behind San Frediano. The most picturesque way to arrive is by parking in the free car park on the ring road outside the city walls and walking in through the passageway under the walls, coming out into the piazza in front of the Collegio. The ground floor of the cloisters were furnished with attractive corrugated cardboard chairs and tables and an entirely functional table football game made of paper, in addition to an exhibition of paper creations by school children. The grand high-ceilinged rooms of the upper floor were ideal galleries for a number of different international artists. Here’s a walk through some of them. Cartasia is over for this year. If you’re planning a trip to Lucca, put July 2016 in your diary now.

For more information about Cartasia, Biennale d’Arte Contemporanea: http://www.cartasia.it/en/biennial/presentation

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed