|

I’m sitting round Franca’s kitchen table, already populated by her husband Peppe, their married son Marco, and Carlo, a builder and work colleague of Peppe’s. Carlo, always jolly and looking well-fed, observes with a sly smile that you can buy ‘extra-virgin olive oil’ in the supermarket for €1,80 a litre. He pauses for dramatic effect, and Franca, taking the bait, says she pays €8; she looks uncertain about admitting she may have been cheated. Carlo immediately supports her. ‘Of course it’s not extra-virgin. How could anyone produce extra-virgin olive oil at that price? You can’t believe it just because it’s written on a label. The cheap stuff is made from the remains of the first cold pressing by adding chemicals and heating it up to extract more oil. It doesn’t have any aroma or flavour at all.’ Franca looks relieved; she buys hers from a woman who comes to the village every year with her new olive oil. She doesn’t even ask to taste it anymore, because after so many years she trusts the woman to supply oil she knows she likes. But if you want to taste oil, Carlo’s recommendation is that you toast a piece of bread and drizzle it with oil while it’s still warm, thus releasing the aroma and flavour of the oil. Franca and I favour pouring a little puddle in our palms and leaving it to warm before slurping it up while also sucking in some air. At olive oil tastings I’ve been given oil in a little plastic cup to warm in one hand with my other covering the cup to keep in the perfumes that are released by the warmth of your hand. Before smelling, you position your nose close to the cup and when you remove your hand, you’re hit by the pungent odour of crushed olive — or not, if it’s a poor oil. Besides the synthetic oil, Carlo’s bad category includes oil that burns your tongue, which in his opinion includes Lucca oil. One of his favourites is a mellow oil from Montecatini. Here I disagree. I love the early oil pressed from olives harvested in October on the Lucca plain, peppery on the tongue and a little bitter at the back of the throat. Carlo insists, ‘The olives have to be completely ripe, black. Then the oil is sweet and mellow. The best is from Genova.’ I’ve tasted Ligurian oil and agree its delicate flavour is well suited to the fish that forms a large part of the diet in that coastal region just to the north of us. Even the Genovese basil is more delicately flavoured than our Tuscan variety, and no self-respecting LIgurian would make pesto from our hard-hitting leaves. We finally agree it’s all a matter of individual taste — ‘a ciascuno il suo’. Walking home, I reflect that my sophisticated oil-producing friends stereotype old farmers, who harvest their olives from late November onwards when they’re fully ripe, as ignorant or greedy. They’re only simple peasants who wrongly believe they’ll get more oil from riper olives and care nothing about the flavour. It never occurs to modish followers of fashion that their traditional neighbours may have just as well-developed palates, and after analysing the old and the new flavours, decide that what they’re used to is best. What do you think?

2 Comments

Super-highways rarely belong to the country they’re in. While racing along with cars and lorries overtaking on all sides, you could be anywhere, except for the blurred glimpses of houses or fields beyond the crash barriers. The village of Molina di Quosa tumbles like a stream down a mountain valley and spreads out on that ribbon of land squashed between the Serchio River and the hills of the Monte Pisano overlooked by the autostrada and the railway that link Lucca to Pisa. And that’s all I knew about it despite my many trips between the two cities. Now a couple of friends and I were heading there at a sedate pace on a small twisting country road for a festival based around new olive oil and chestnuts, vintage cars and Vespa scooters, with a wild mushroom exhibition thrown in for good measure. [November 2020: Due to the perversity of IT, several years ago all the photos were stripped off this blog. Most have also disappeared from my photo library and that of my friends, in particular nearly every photo of olive oil. Here you see what the microchip demons have chosen to leave behind.] It must be a winning combination since before we even reach the village, parked cars line the verges and coming into the village itself we nose up to a queue of stationary cars held up by a policewoman to let the crowds cross the road. We abandon the car in a field that has been requisitioned as the festival car park and walk back along the main road, passing several large elegant villas skulking behind high walls and heavy iron gates. I must read that history of Pisa, in Italian, that I bought at Pisa airport in one of my fits of wanting to know everything about everything between the sea and the Garfagnana. It might explain why anyone with money and status would have wanted to live on the Serchio River bank kilometres from anywhere. The original main street of the village runs perpendicular to the road we drove in on, up the side valley. We turn up it between shops and houses on one side and, on the other, stalls selling craft jewellery, kitsch wooden carvings and honey. After a porchetta stall (we make a mental note to return for lunch), we come to the first roasting chestnuts and the first olive oil stall. The signora tells me that her olive groves are at Montemagno, but she takes the olives to the frantoio (olive mill) at Vicopisano which is an excellent modern press. The olives were picked yesterday and pressed and bottled early that morning in time for the festival. The owner of the olive press arrives just in time to verify both the quality of his frantoio and the timing of her pressing. She offers me a slice of bread doused with oil — these oil anteprime (previews) are the only times I’ve ever seen oil poured over bread in Italy, but I notice a stack of small plastic cups and ask to taste the oil in one of them. She agrees this is the best way to taste the oil, but ‘many of us’, she circles her hand to encompass the anonymous bystanders, ‘are ignorant’. She pours a small puddle of thick green oil into the cup. I hold the cup in one palm to warm it while keeping the other hand firmly clamped over the top. After a minute or so, I put the cup to my nose and raise my hand enough to sniff up the pungent aroma. Then I slurp up some of the oil with lots of air and taste the strong heady flavour, bitter at the edges and peppery at the back of the throat. The most interesting producer for me is a young man who is offering comparative tastings of his last year’s oil and this year’s, also just pressed that morning. But these first few bottles contain oil only from the bitter leccino variety of olives, since they’re the ones at the top of his slopes and ripen earlier than the sweeter frantoio and moraiolo lower down. Last year’s bottles contain a blend of all three varieties, and have a decidedly gentler flavour, partly due to the blend and partly a result of ageing in the bottle. His azienda is organic and he’s joining forces with some other producers, including a norcino (pork butcher) to present taste workshops. He invites me to visit.

This morning in my letter box in Casabasciana I found an envelope from a friend in England which contained a piece from the Financial Times of 19 September. In his column ‘The Slow Lane’ Harry Eyres writes about his return to Sommocolonia after a gap of 30 years. He captures the spirit of small villages in this rural mountain area perfectly when he realises: ‘that people make places…The poor architecture glowed with an inextinguishable human warmth’. There are some architectural gems which he may have missed, but he’s right about the people. People who come on my gastronomic tours to the Garfagnana are always touched by the warm welcome they receive from the small, artisan producers I take them to visit. Thank you, Harry, for expressing it so poetically.

It was a rabbit. Renato cut it into pieces for cooking in umido (stewed) and showed me the little wedge of white tissue he removed from behind each knee. He smelled it. No scent, but when cooked it would give the rabbit the ‘dirty’ flavour people didn’t like. Next I turned to Eugenia, Renato’s wife and a good butcher in her own right, to check the recipe. The usual garlic, rosemary, white wine and tomatoes? That’s it, then add porcini, already sliced and sautéed with garlic and nepitella (calamint), at the end of the cooking to season it. She wanted me to understand that people don’t usually add porcini to rabbit these days, but they used to so it’s OK to do it. Every recipe needs authenticating by the past.

I go up to the village shop, which sells meat as well as almost everything else you could possibly want, to order a guinea fowl for lunch tomorrow. I explain to Renato, the butcher, that I really want a rabbit, but I’m not sure whether the one American and two Brits who are coming to lunch like rabbit. Many people, especially the British, don’t. ‘I’ve heard they think of them as pets, like cats’. ‘Perhaps it’s partly that, but’, I counter, ‘many people say they find the flavour “dirty”’. Renato understands perfectly. He explains that a rabbit has tiny glands, particularly behind the knee, but other places as well, which cause that ‘dirty’ taste. I can be absolutely sure when I buy my rabbits from him they won’t have that flavour, because he removes every little gland himself. With that reassurance I tell him that if he can’t get a guinea fowl, I’ll take a rabbit. I’m almost hoping he can’t get the guinea fowl after all.

I’m planning the menu for dinner with a couple of friends tonight. When I went into the village shop this morning, there was a wooden crate showcasing several fresh porcini, collected by the daughter-in-law of the shop owners. Opportunistically I decide to make an insalata di porcini, by slicing the small young ones very thinly, dressing them with extra-virgin olive oil, that I bought directly from the olive estate, and lemon juice. The garnish is a sprinkling of nepitella (also called mentuccia in other parts of Tuscany). Calaminta nepeta is an aromatic herb which grows wild in the mule track in my village and all over Tuscany. It has the strange characteristic of smelling different to different people. Some say mint, but many to people it's more like marjoram or basil. The rice harvest in the Piedmont is happening now, and I still have some rice from last year. It must be used. I choose a package of riso venere, a black whole-grain rice, that was given to me by the co-operative that distributes the farro grown by my friend Paolo Magazzini. I know they only represent small, artisan producers of very high quality. The specially aromatic rice combines well with seafood, so I plan a seafood risotto. I visit the mercatino (outdoor market) in Fornoli to buy some calmaretti (small squid), gamberi (large prawns) and scampi (Dublin Bay prawns) from the fishmonger who comes once a week from Viareggio on the coast with the fresh catch. I don’t have to tell him what I want. I tell him I’m making risotto al mare for three, and he tells me what I need, accompanied by an oral recipe — he is passionate about fish, knows exactly where each fish on his stall comes from, when they’re in season and has very fixed ideas about how they should be cooked. Garlic, parsley and white wine for the risotto. I tentatively suggest a little onion. He looks horrified. You only use onion with frozen fish to disguise the fact that it was frozen. It will kill the flavour of fresh fish. The contorno (vegetable) will be bietola (Swiss chard) from my orto (allotment, veg patch), steamed and sautéed with garlic. Yesterday my friends from Zato gave me some green figs and new walnuts from their own trees. They’ll be good for dessert. Ticking off the ingredients for my meal, only the lemon comes from someone I don’t know. All the rest I can trust implicitly to be fresh, wholesome and to taste exactly as it should. Tours related to this blog

Cook a coloured meal: Tastes & Textiles: Woad & Wool Pick olives, press oil and learn how to taste it: Autumn in Tuscany Franca and Peppe have promised to take me porcini hunting as soon as the funghi ‘nascono’ (literally: are born) after the rains. Looking out my window onto the the main street in the village (steep and cobbled, no cars), I see Anna Rosa and Ebe carrying baskets full of plump multicoloured funghi. It’s time to visit Franca and Peppe to beg a place on their next foray into the chestnut woods.

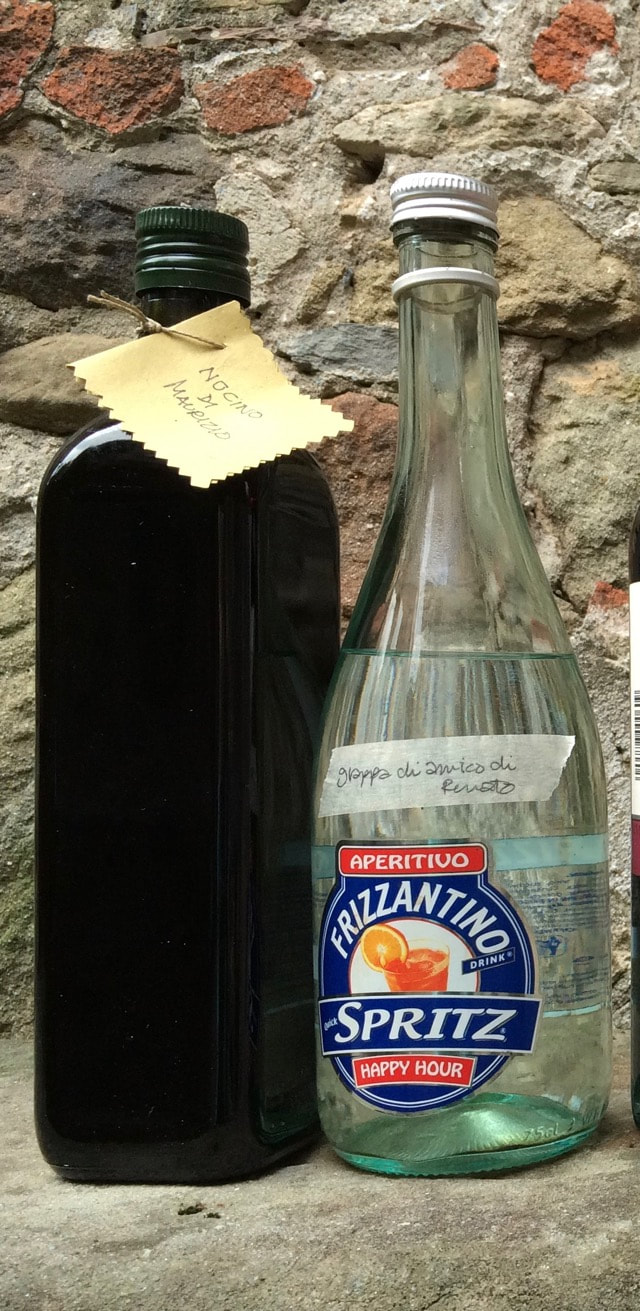

It’s 6.15 pm when I ring the doorbell, apprehensive that I might be interrupting dinner preparations, but Franca welcomes me with a beaming smile and makes space at the kitchen table — already crowded with her husband Peppe, their married son Marco, and Carlo, a builder friend and work colleague of Peppe’s. Having assured me that they’ll let me know about future porcini hunts (and the chestnut harvest, except that the chestnuts have only just started to drop, so it won’t be this week). Franca extracts a bottle of limoncello from the cupboard… Carlo turns it down (which I would have thought impolite) and out comes a bottle of single malt whiskey instead, which I happily accept as well, complimenting them on their well-stocked liquor cabinet. I wish I’d had time to ask how they’d got it, but Carlo is already saying that what he really likes is a good grappa, like the one he has from Friuli, north of Venice, with the scent of the grapes still in it. If this is a hint, it doesn’t send Franca back to the cupboard, and Carlo shifts to the wine of Friuli, which he also admires. Chianti is good too, he says, a real Chianti of course, not the ones that just say ‘Chianti’ on the label. Had we heard about the tanker they filled with water and sugar in Sicily? By the time it reached Milan, it had fermented. All the wine ‘manufacturers’ had to do was to add some red colouring and bottle it. They make a hefty profit, he claims, selling it at just €1,50 a litre. But if you know what goes into producing a good wine, you’ll know not to trust such a cheap bottle. Your neighbours’ wine is in a totally different category; you have firsthand evidence of it. Carlo thinks this year should be an excellent vintage here in Casabasciana. He tasted Giuliano’s grapes as he was passing last week with the newly harvested bunches. They were good and sweet after the hot, dry summer, but it remained to be seen whether the alcohol content would be 13% like last year’s or drop down to the 12% of 2007. I hope I’m invited to taste it, even though it will probably taste rough to me. The important thing that applies equally to fine wines and little local wines is that knowledge of the producer is what counts. It’s what keeps you from being made a fool of, and guarantees you get a genuine product. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed