|

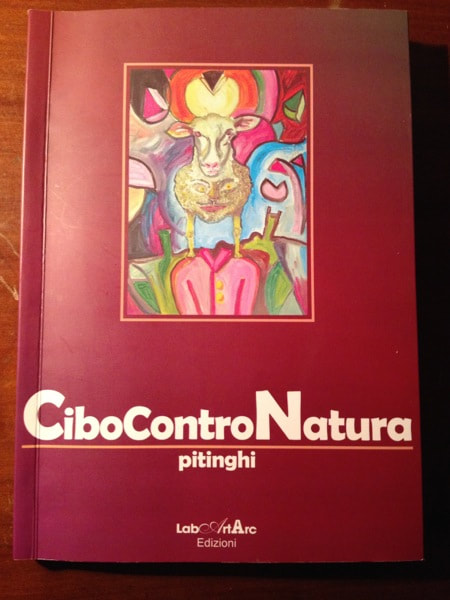

The first year I went to the International Truffle Fair at San Miniato one of the sideshows was a small bookstall. A woman thrust a book into my hands and explained exasperatedly, as she touched a finger to her head, that it had been written by her loopy husband. Perhaps he had insisted she listen as he declaimed each of its 121 pages. As I read the polemical Cibo Contro Natura (Unnatural Food) I could hear Signor Pitinghi shouting his manifesto while gesticulating with his hands. The flowery language can be over the top, but far from being mad, it’s full of insights into a passing Italian food culture. This is a frustrated man with the memory of a flavour in his mouth which he finds harder and harder to reproduce in the kitchen. Perhaps his wife is a bad cook, but this isn’t what he laments. He’s dismayed by the swamping of natural food by industrial food, of slow food by fast food, of real cooking by virtual cooking, of found ingredients by packaged and marketed products. Having read a chapter or two, the book itself got swamped by other literature I picked up at other food fairs and only re-emerged recently. My experience of Italian culture, not to mention my comprehension of the Italian language, has grown in the intervening years and many of Signor Pitinghi’s ideas set me thinking and exploring half-trodden paths. Among his many provocative statements is the chapter title ‘Bisogna provare a cucinare o almeno…a cuocere’, which translates literally: ‘It is necessary to try to cook or at least…to cook’. The dilemma for me is one of linguistics and culture; for him it’s one of action. I check my excellent Italian-English dictionary by Ragazzini and Biagi just to make sure both cucinareand cuocere mean ‘to cook’. They do, but there’s a hint of a difference. Cucinare can also mean ‘to do the cooking’. My Italian friends sometimes correct me for using one or the other incorrectly, but I haven’t quite got it yet. Back in San Miniato having lunch with Riccardo and Amanda, my truffle hunter and his wife, I ask them if they can enlighten me. We’re eating a typical Tuscan lunch, a simple roast chicken with potatoes and onions. Amanda explains that if she had bunged the chicken into a roasting pan and stuck it in the oven until it was done, that would be cuocere. Instead, she had seasoned the chicken, browned it in olive oil, deglazed the pan with white wine, put it in the oven and basted it from time to time. She’d cut up the potatoes and onions and added them to the roasting pan to cook and become glazed by the juices of the chicken. All very simple yet this is cucinare. Now I could transfer it to my own culture: ‘I can boil an egg, but I can’t cook’. Pitinghi reminds his Tuscan readers how simple their cuisine is and muses on whether in our ‘global village’, with mother at work and incessant television cooking programmes interleaved with adverts for snacks full of preservatives and breaded fish fingers ready for frying, the family no longer knows how to keep traditions alive, especially those of cooking and local food. He ends with this exhortation ‘to all of us: “let’s try to cucinare!” or at least, if this verb seems too challenging “let’s try at least to cuocere something”.’

0 Comments

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed