|

Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

2 Comments

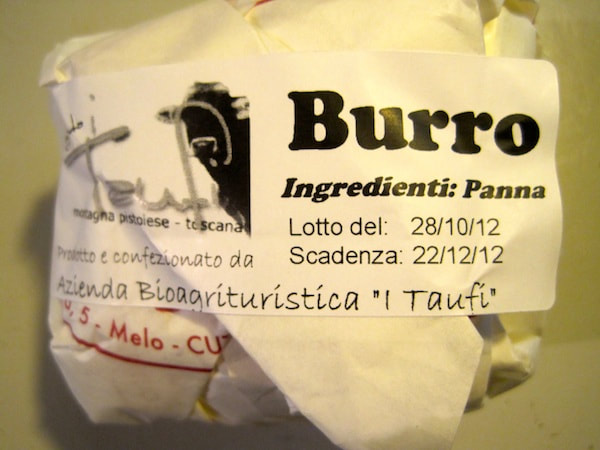

The butter is made on an organic farm from cream of cows on the farm at Cutigliano (PT) and sold in a shop 44 km (27 mi) away in Ponte a Moriano (Lucca). Delicious, especially on my sourdough bread warm from the oven (organic flour from the Garfagnana, natural leavening, sea salt from Sicily, water from a spring above my village).

Every morning I go down to the fig tree and pick three figs — there are many more, but after gorging on them for a week, three a day is the perfect number. The yoghurt contains milk and starter culture — nothing else. It comes from a dairy farmer near Lucca; I return the jar and the farmer sterilises it and reuses it. I buy it at a shop in Marlia called Effecorta, which means ‘short F’ and stands for Filiera Corta or short supply line. It’s a joke on the name of the supermarket chain called Esselunga, ‘long S’. I don’t know what it stands for, but you can bet its yoghurt comes from farther away than 10 km and is produced industrially. I bought the prosciutto at the shop in my village Casabasciana. It’s called prosciutto toscano or prosciutto saporito, which means tasty, because it’s more highly spiced than the Parma variety. It’s saltiness is the perfect foil for the sweet figs.

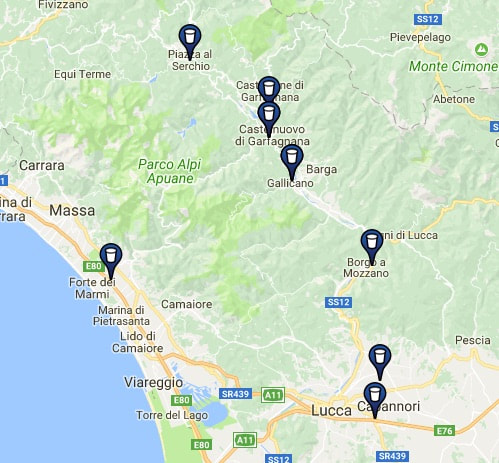

On the way back from a cooking lesson I’d arranged for clients, I’m crawling along at a Slow Food snail’s pace (no doubt infuriating the rush-hour drivers behind me) when I spy the little wooden hut I’m searching for. The hut — a kind of mini-barn — shelters a machine that dispenses unpasteurised milk almost straight from the cow and is part of an Italian rural development programme to shorten the supply chain and put consumers’ money directly into the pockets of farmers. The farmer tests every batch of milk with the lab equipment in his barn. Health and safety officials also check the milk regularly. There’s a website where you can find all the ‘mechanical cows’ in Italy. Here are the ones near me. A crowd of customers is gathered round, each hugging one or more empty glass bottles. It looks like happy hour at a bar, but as I get closer, I realise they’re waiting for the young farmer to clean and refill the ‘mechanical cow’. The landscape being more industrial than pastoral in this part of the Capannori, I ask the farmer how far away his farm is. He pulls me a few steps to one side and points through a gap in the buildings to his cow barn, about half a kilometre from us. Not many food miles required to fill the machine. Sensing a captive audience, he signals me over to his milk truck and opens the side door to reveal a secret cargo… Lying on the back seat is a large bunch of stringa. His own produce he proudly explains, harvested that afternoon for a customer who will be arriving any moment, so he regrets he can’t sell me any. ‘Stringa’ means ‘shoelace’ and refers to a small diameter green bean, grown only in the Lucca plain and nearby Versilia, that reaches 70–80 cm in length — more a bootlace, really. I explain that I organise gastronomic tours to visit small producers and ask whether I could bring some guests by to see his farm. He suggests I telephone next time I’m passing and he’ll show me around. He returns to his work, now filling the bottle dispenser with new glass bottles, for new customers or those who have forgotten theirs at home. By now the crowd has dispersed and I fill my own bottle. The milk costs 1 euro a litre and, for small consumers, you can buy it in units of 100ml, rather than having to buy a whole litre at once. It tastes intensely of milk, unlike the white liquid one buys at the supermarket, which costs €1,40. I say arrivederci, but he’s loath to lose a sympathetic ear. He looks indecisive, then makes up his mind, goes to the truck and steals a large handful of stringa from the bunch on the seat. ‘Here’, he says, ‘You know how to cook them, don’t you?’ ‘Yes, stew them with onions, garlic and tomato.’ ‘They’re delicious with rabbit, but only with my grandmother’s.’ He reminisces, ‘When I was a boy, I refused to eat rabbit if my mother bought it from the butcher. It didn’t have any flavour compared to my nonna’s. But she’s gone now, and I don’t have time to keep chickens and rabbits’, he continues wistfully. I promise to return soon, and bear my booty home to stew my stringa.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed