|

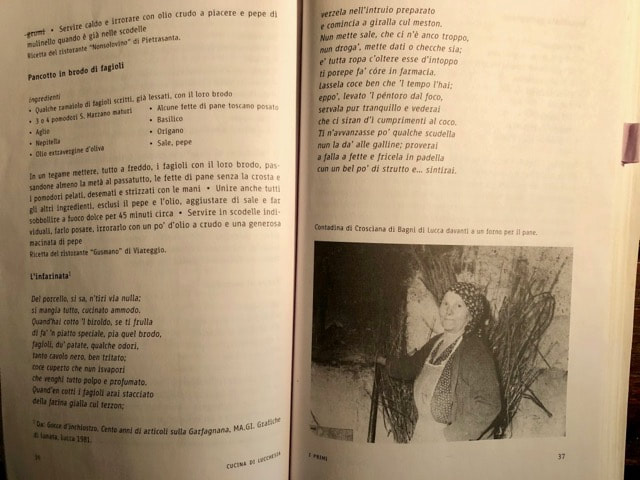

Some dinners are tweets: heat up the leftovers and pour a glass of wine. Others are more like short stories taking more time and connecting you to other people and places. FRIDAY MORNING I take the kitchen compost down to the orto (vegetable garden). The cavolo nero is beginning to flower. I’d better use the remaining leaves. I ponder what to cook as I walk back up to the house. I settle on infarinata. I'm remembering the infarinata we had at the Vecchio Mulino during the Advanced Salumi course that had just ended. FRIDAY AFTERNOON I have a good idea of the ingredients — broth from cooking biroldo (a blood sausage which I can get at my village shop, but not the broth), beans, cavolo nero, some odori (onion, carrot, celery) and cornmeal. Since I’d never made it at home, I decide to check a couple of my local cookbooks. I bought Le Ricette di Marilena many years ago from the inimitable Andrea Bertucci at the Vecchio Mulino. She’s from Fosciandora, which is on the southern edge of the Garfagnana. When I think of that area, I think of Marina Donati, the weaver to whom I take guests on my Tastes & Textiles tours. Marina is a courageous woman who decided to preserve the traditional patterns of the Garfagnana instead of creating her own. She sold her scarves, tableware, rugs and handbags at weekly markets, packing and unpacking her van and setting up her stall single-handedly. Marilena wants me to throw dried beans pre-soaked overnight, finely chopped cavolo nero, squashed garlic, potato and onion both finely chopped, a stock cube (which I refuse to use) and salt and pepper into a pot of water and boil for two hours. Halfway through I’m to add some pork stock. After two hours I whisk in the cornmeal and stir continuously for 40 minutes and serve hot, seasoned with a drizzle of extra-virgin olive oil, or leave to get cold. The leftovers can be cut into little squares and fried. The other cookbook is one I bought when I first arrived in Lucca in 2004. The author Emiliana Lucchesi was a researcher and collector of recipes. Her book includes recipes gathered from the mountains of the Garfagnana to the beaches of Viareggio. It ranges from recipes of the peasants to those of the well-to-do, from home cooks to restaurant chefs. She relates stories and legends. I’m very fond of it. Emiliana’s recipe is similar yet different. She wants me to use fresh borlotti or scritti beans, which are summer vegetables, and basil, which dies at the first frost. Yet she herself states that infarinata is a robust and tasty winter dish. She suggests adding some pork skin, which might give a hint of the missing broth from biroldo. She cooks the beans separately, sautés the odori (which include carrot and celery) to which the beans and their liquid are added. There’s a nice touch about drizzling the olive oil on the hot dish in the form of a cross. Even the name of the dish is inconstant. Marilena calls it ‘farinata’ and includes in brackets the alternatives ‘menomatoli’ and ‘pacchiarini’. Emiliana calls her recipe ‘infarinata garfagnina’, but also notes that at Pietrasanta and Querceta on the coastal plain it’s known as ‘intruglia’ or ‘incavolata’. She prints ‘L’infarinata’ which gives the whole recipe in verse in the Garfagnana dialect (or perhaps Garfagnana Italian). And to complicate matters further, if you ask for ‘farinata’ at Massa, you’ll get what we in Lucca call ‘cecina’, a chickpea flour galette cooked in a shallow copper pan in a wood-fired oven. I recently found Mauro Agostini who makes the pans, and we’ll be going to visit him during the Tastes & Textiles: Wine to Dye For tour in September. Not only will we learn how the pans are made, but also how to make cecina and enjoy lunch cooked by his son-in-law Jimmi in a battery of copper pots. By now I’ve spent a pleasant hour or more (who’s counting) exploring the variety of traditions of a single dish in the relatively small area of Lucca Province. That’s what Italy is like: confusing and endlessly interesting at the same time. I don’t know where the idea of a single Italian cuisine came from. SATURDAY MORNING Up to the shop to do my weekend shopping. I ask Eugenia, the owner and one of my cooking mentors, how she makes infarinata. She starts with lardo (fresh pork back fat) minced with odori. I must remember to tell participants on my salumi courses about this delicious confection which you can use when making minestrone or spread on hot toasted crostini. She sautés more odori in the melted lardo, adds the pre-soaked and boiled borlotti beans and then proceeds more or less like Emiliana, but without the basil and pork skin. Since this is the Casabasciana recipe, I decide to proceed more or less with her recipe. I go down to the orto to pick the cavolo nero leaves. What will become of it this year? I think about Penny, my friend who does more of the work than I do but is locked down in England. Rolando who digs it every spring is locked down in his own village in the valley. SATURDAY AFTERNOON I put the beans to soak. I’m slightly embarrassed. The beans aren’t from the Garfagnana; they’re ‘Cera’ beans from Agriturismo San Cassiano, the farm where we stay during the mozzarella course. It’s in southern Italy, in the region of Campania where you have to go for the best mozzarella di bufala. Andrea the farmer and his mother Rosanna the cook share precisely my philosophy about agriculture and food. They are affectionate and generous to me and my guests. I always load up with their beans and Rosanna’s jams, both of which taste intensely of themselves. I was especially sad not to be able to see them due to having to cancel the mozzarella course at the end of March because of the coronavirus. SUNDAY MORNING I simmer the beans with a crushed clove of garlic and a few sage leaves. SUNDAY LATE AFTERNOON I unhook my copper paiolo from next to the fireplace. The paiolo has a slightly rounded bottom and a sturdy iron handle by which you hang it over the fire. It’s ideal for making soups, stews, polenta and infarinata. I bought mine in one of my favourite shops in Lucca in Via San Paolino, nearly opposite the church that the Puccini family frequented. It’s stuffed full of every type of home, kitchen and agricultural implement you can imagine, mostly made of metal, but not all. I chop the onion, carrot and celery and sauté it in olive oil. I add cavolo nero and potato, the beans and their liquid, some strips of skin from prosciutto (which Renato, Eugenia’s husband gave me Saturday morning) and more water and start them simmering. I light the fire in the kitchen fireplace. When the vegetables are cooked, I slowly add the farina di formenton otto file (flour of eight-row maize) which I got last time I visited Ercolano Regoli at his water mill in Pieve Fosciana. Ercolano owes his name to Beato Ercolano, a 15th-century Franciscan friar who founded what is now Agriturismo Ai Frati, where we stay during the Tastes & Textiles: Hanging by a Thread tour. Most people in the Garfagnana have nicknames, but Ercolano is so kind and good, the essence of a saintly being, that he is always called by his real name, Ercolano. I stir with a spurtle, a turned wooden stick used by the Scots when making porridge. In reality, polenta is also a porridge, a mush or pap which can be made from many types of flour. In the Garfagnana we also make polenta dolce (sweet porridge) from chestnut flour. As I stir, I think about my dear friend Sarah who gave me the spurtle. I’ve known her for decades, from her days as administrator for the Academy of Ancient Music, then tai chi lessons together which led her to study the Alexander Technique which she now teaches in Edinburgh. I learned from Alvaro Ferrari, master polentaio (polenta-maker) of the Garfagnana when I first arrived here, that 40 minutes is not long enough to adequately cook our whole-grain formenton otto file cornmeal. It requires a minimum of 1 hour, and he adds, if your guests are late, all the better. But the best secret I learned from him is that you don’t have to stir your polenta continuously. Just drape a damp cloth over the top of the pot, cover it with a lid and simmer as slowly as possible for an hour. No stirring! You can get on with preparing the rest of the meal. Whether this method would work with a stainless steel pan, I can’t say. When cooked in copper, it doesn’t stick to the bottom. I hang my covered paiolo on the hook in the fireplace, making sure the cloth isn’t hanging down the sides (my cloth is singed to remind me not to make that mistake again). SUNDAY EVENING I open a bottle of Alessandro Bravi’s Garfagnina Rosso wine. Alessandro makes it below Camporgiano, north of Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, the administrative capital of the Garfagnana. His sangiovese grapes grow in vineyards even higher in the Garfagnana and don’t ripen until the end of October or early November. Alessandro likes a challenge. The aromas and flavours of the finished infarinata are beyond my powers to describe: the pungent scent of this season’s olive oil as I drizzle it over the hot infarinata, the intense flavour of corn and beans, the slight bitterness of the cavolo nero and the throng of friends who have been present along the way, if not in body, then in spirit. A happy ending to a short story.

4 Comments

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed