|

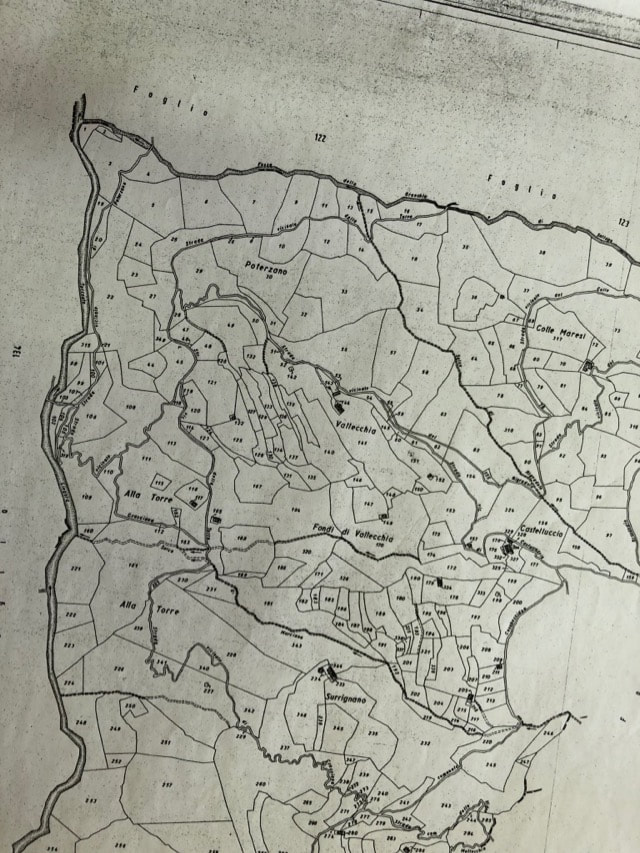

What is it about an abandoned house that makes it so fascinating? Does it offer an escape route for our imaginations, like a fairy-tale, conjuring up fantasies of life in other times? Or perhaps it helps us feel connected to the past and ultimately to all humanity? Or maybe it’s just simple voyeurism: peeking through the curtains at a lost way of life? Whatever the reason, I felt a surge of curiosity when I first discovered the roofless casa colonica, or farmhouse, at Surignano. I approached the house on a well-defined dirt drive that cut through the chestnut woodland. It sat on the southwestern edge of a gently sloping plateau near a stream crossed by a still intact wooden bridge. I thought it must have been the house of a well-to-do landowner. The imposing stone building stands three storeys tall. At ground level two impressive arched doorways lead into the former cantinas, which would have housed animals and farm equipment. There were three or maybe four spacious rooms on each of the floors above, though the floorboards and beams are too rotten to risk exploring. Questions filled my mind. Who had built this magnificent house? And when? Who lived in it? How did they make a living? That was in 2009 before Saperi & Saperi had taken off and I still had free time to explore along woodland paths leading out from my village of Casabasciana. In 2020, the year of Covid-19, with no tours or courses taking place, I’m drawn again to explore in the direction of Surignano. It’s along what was the main road to Brandeglio, the village I can see from the windows of the upper floor of my house in the village, 2.5 km (1.5 mi) as the crow flies to the southwest across the Liegora River. This ‘main road’ was in fact no more than a footpath, because until the 1960s walking was the only mode of travelling between villages. It is still well used by walkers and maintained by men of the village and a group that uses it for an annual mountain bike event. As I walk I try to imagine the landscape 70 years ago. People have told me that all the land was terraced and cultivated with cereals, vines and olives. Everyone had a few sheep, a couple of pigs and maybe a cow or two. It’s almost impossible to visualise what it was like. I can see remnants of dry-stone walling, but not even a ghost of those numerous families working the land. My view in every direction is blocked by trees — mainly chestnut infested by acacia, brambles, wild clematis, broom and tree heather. After 30 minutes I arrive at Castelluccio, the farmhouse where my neighbour Domenico was born and brought up. It is not abandoned. He goes there every afternoon to keep the roof intact and the brambles and wild clematis at bay. It and the surrounding land give a hint of what the countryside would have looked like in the past. He arrives in his 4x4 Fiat Panda on the strada sterrata (dirt road) that descends from Crasciana, the village above mine. I often find him there if I stop to drink the icy cold water his grandfather piped in from a spring higher up. I cross that road and continue southwest towards the Liegora River, now on another strada sterrata suitable for a 4x4. I pass a couple of crumbling buildings that must have been either metati (drying houses for chestnuts) or sheds for storing equipment closer to fields. Another 10 minutes and I reach the road that I remember leads to Surignano, but I’m sure I need to take a fork off it to the left. Now I notice that a logging operation has cleared a huge swathe of land and, I presume, erased the former drive and destroyed the neat terracing. Continuing straight I come to log piles surrounded by carpets of spring flowers. I find the old wooden bridge, now nearly invisible and decaying under velvety green moss. Finally, dropping down through a thicket of birch saplings, I emerge behind the house. Struggling around to the front the façade shocks me, like seeing a friend after 11 years, so much older, greyer and wrinkled. What a story this house must be able to tell! Layers of history of the land and the people who lived here. But it is mute, sulking after decades of neglect. By now my Italian is up to asking questions of my neighbours in the village. At first they aren’t very interested, but the few clues they throw me are more tantalising than having the whole story land in one indigestible bundle on my doorstep. – Have you found Cerro? It was even more beautiful than Surignano. –You know, my mother Olga lived there. –The forestry commission planted that ugly fir tree plantation without even asking the owner’s permission. –Did you see the church San Martino on the way? On the left, diagonally across the corner. Only a part of the façade is left. It’s from the 8th century. – My grandmother lived at Lupinaia. I often walk out to look at it. –It’s been restored, by a family perhaps from Ponte a Moriano. But it belongs to the frazione of Crasciana, not Casabasciana. –I heard that the wife doesn’t like it, so they hardly come anymore. –There used to be a path opposite the Croce del Bacco that led to Collemaresi. –You can also get there from just before the path crosses the Rigrado stream, but it’s probably blocked by brambles. –Go straight down from the Metato di Bacco to the three pine trees, and then straight down another 100 metres. You can’t miss it. Here, I’ll show you the pine trees from my gate. –Memmo Nardi lived there. His grandson Guglielmo still comes to Crasciana every winter. –Vallecchia is below Castelluccio. –The Logi family were contadini there but they moved into the village in the ‘50s. –Someone took me there once. If I can remember the way, I’ll take you. One by one I found all six farmhouses and their attendant outbuildings. All but Castelluccio and Lupinaia are knee-deep in brambles and wreathed in ivy and wild clematis, all partially collapsed. They were built in the 1780s. All seem to speak of a prosperous past, but now I know that the prosperity was mainly that of the landowners. Apart from Domenico and his family who owned Castelluccio, the inhabitants were tenant farmers paying rent, usually a percentage of the produce, to the owners. Their descendants tell me that Collemaresi, Cerro, Vallecchia and half of Surignano were owned by the Finucci family, who lived in the grand house opposite the one I rent in the village. They are gone too. The houses were large because families were large. Typically couples had 5 to 8 children. When sons married, their wives came to live with them in the family home, and grandchildren swelled the head count. Jobs on the farm were numerous and required many hands to plough, plant, prune, harvest, care for animals, make cheese, slaughter the pig and cure the meat, cook, clean, weave, sew, cut firewood, maintain buildings and equipment. But it wasn’t all work. In the long winter evenings they would gather round the kitchen fireplace for the veglia, storytelling and playing games. In addition to the houses themselves, there is the network of mulattiere (mule tracks) and paths that connected them to each other, to sources of water and to villages with shops, schools, markets and craftspeople. They reveal social and economic relationships. Domenico showed me a set of cadastral maps in the ex-schoolhouse, documenting land ownership around the village. I asked our village president to have them scanned so I could study them. Unfortunately the plots of land are identified only by numbers, and I don’t have the key to who owned each one and how ownership shifted. But on them you can see the old paths. Trying to find them in the woods is a gloomy task, and highlights how inadequate are the number of able hands left in the village to maintain them. During every storm trees come down blocking paths, landslides cover others, cobblestones wash out, people no longer use them, boar and deer find other routes, acacia and broom colonise the abandoned tracks. Most of the villagers are more realistic than I am. They know maintaining the countryside as it was would be a series of fruitless battles lost to the inexorable forces of nature. But occasionally my curiosity has inspired someone to recover the past. We now have a WhatsApp group called Casabasciana in Storia (Casabasciana in History) where people occasionally post information and photos from the past. One day I asked Giovanni how the people at Surignano and Cerro got their water. He told me there’s a spring halfway between them with a lavatoio (laundry), but I couldn’t find it. Then suddenly a couple of days later, he posted a photo of it to the WhatsApp group. He had gone out and cleared the brambles, and described to me exactly how to get to it. Many of the farming activities are ones you learn about first hand on my tours and courses, because I’ve found people who, with a bit of mechanisation and marketing, are still making mixed farming pay at the family level. But it’s more difficult now. That’s partly because almost no money was required right up until the 1960s. Farms were self-sufficient. There was very little that needed to be bought in. But after the war, in the ‘50s and ‘60s the introduction of the internal combustion engine catapulted subsistence farmers into the cash economy. They needed tractors, cars, chainsaws and the petrol to run them. They could no longer repair everything themselves, so they had to pay for expertise to keep their machines running. Finally, agribusiness dealt a mortal blow. My next blog will mourn the death of all but the most resilient small family farms.

2 Comments

Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

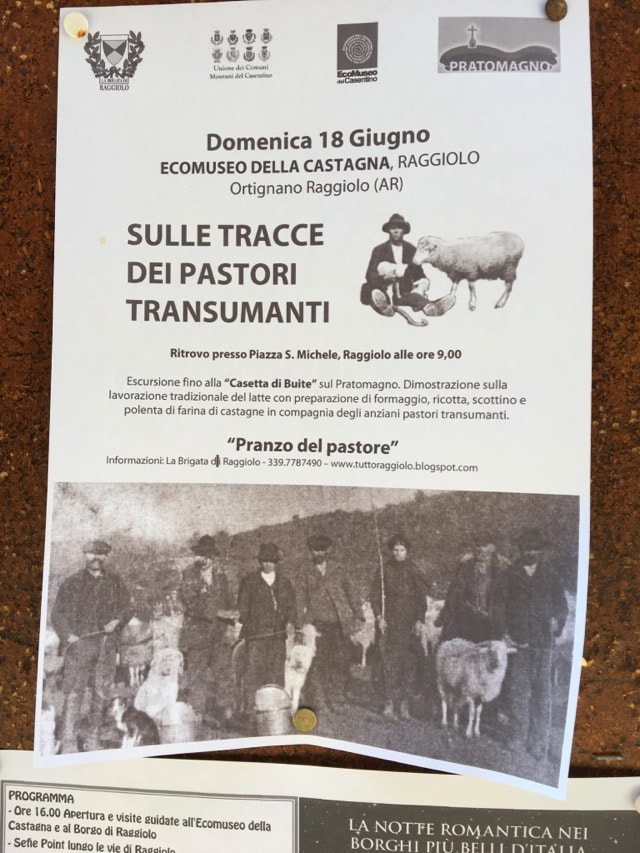

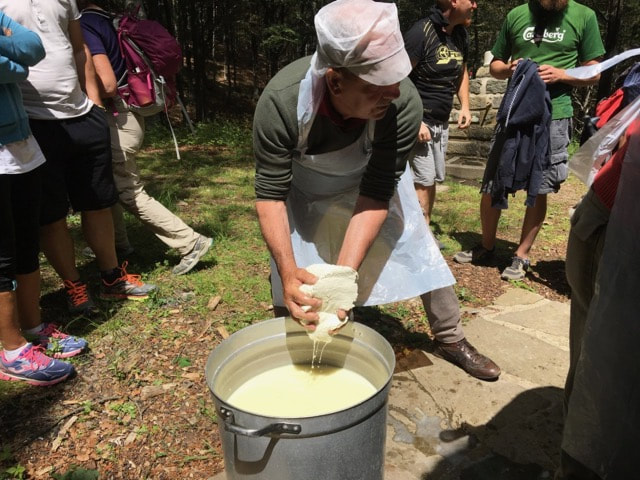

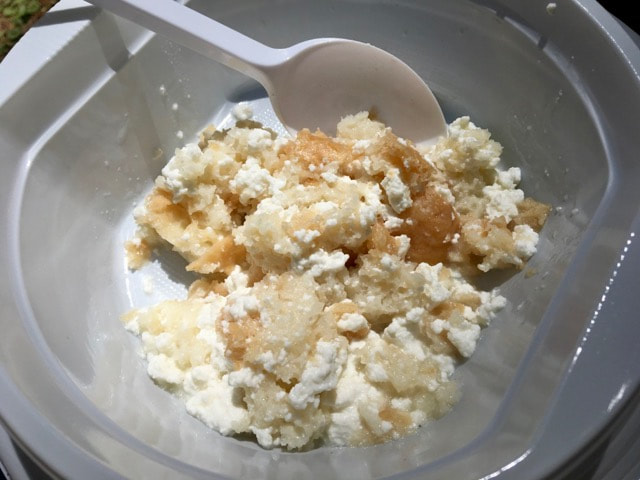

This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html It was martedì grasso, Fat Tuesday, the last day of Carnival before Lent, and I was in Oristano in Sardinia. Oristano has celebrated this day for a long time, 552 years to be precise, as the festival Sa Sartiglia. You can imagine that in over more than half a millennium it has accumulated many meanings and observances. At its most basic and obvious it’s a giostra, a joust like the one at Arezzo with a feat to perform at the end of a charge on horseback. At Sa Sartiglia the horseman (with one or two exceptions they are all men) attempts to insert his lance in a small hole in a star dangling by a thread while galloping at full speed.

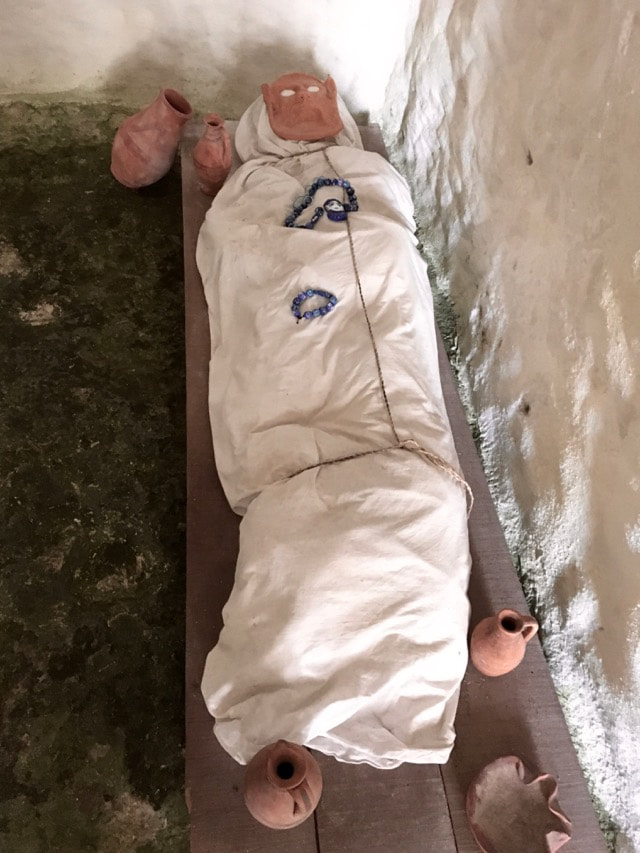

At a more fundamental level is the idea of trasvestire. Although our noun ‘transvestite’ derives ultimately from the same Latin root as this Italian verb, don’t be fooled. In Italian the word means simply ‘to disguise’ or ‘to dress up as’ anyone or anything. For Sa Sartiglia, farmers and craftsmen dress up as knights and joust with fate. In the past it was their day of glory in which to display their horsemanship and affirm their equality with the nobility. Wearing their eerie, expressionless white masks, they disguise their wrinkled, bronzed peasant faces. Still curious about dressing up? Read the rest of the blog at: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/cross-dressing-in-sardinia/ Even more curious and want to see for yourself? Come with me to Sardinia on my Celebrating Sardinia tour: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/small_group_tours/celebrating-sardinia/(click on the tabs below the introduction to see all the details). There’s one place left on this year’s tour from 28 April to 7 May, and in case you like to plan further ahead, dates for 2018 are already there too. The southwestern corner of Sardinia is called Sulcis. The word derives from the Carthaginian city of Solki. This is just one tiny example of the cultural palimpsest that makes up present-day Sardinia. Before the Carthaginians when the Phoenicians began visiting Sardinia in around 900 BCE, they encountered people of the Nuragic civilisation, which originated in about 1800 BCE. The ruins of their gigantic stone towers and settlements still dot the countryside; 7000 of them remain. Hard on the heels of the Carthaginians, the Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Spaniards, Pisans, Genovese and Piemontese all demanded their turns on the island. It’s no wonder that coming from Italy you feel as if you’ve arrived in a foreign country But it wasn’t the distant past that drew me to Sardinia. Some of the women coming on my September ‘Tastes & Textiles’ tour wanted to visit a woman who weaves with the fibres of the beard of a giant Mediterranean mollusc, and they asked me to take them. Barely credible, I thought, but her workshop had a website which placed it in the town of Sant’Antioco, on the Island of Sant’Antioco in the territory of Sulcis. Here was the ideal excuse to visit Sardinia, which I knew only from its pecorino sardo cheese and Vermentino wine…

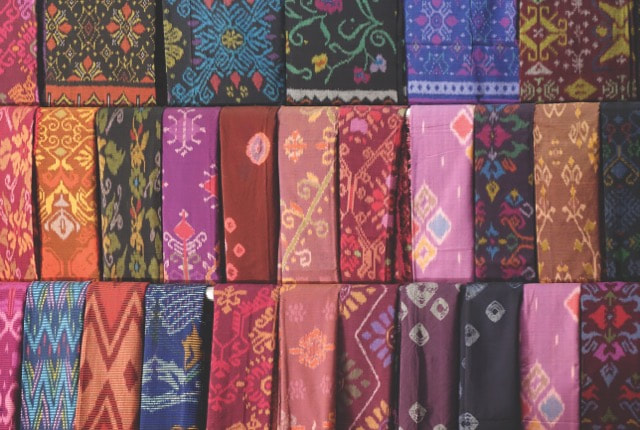

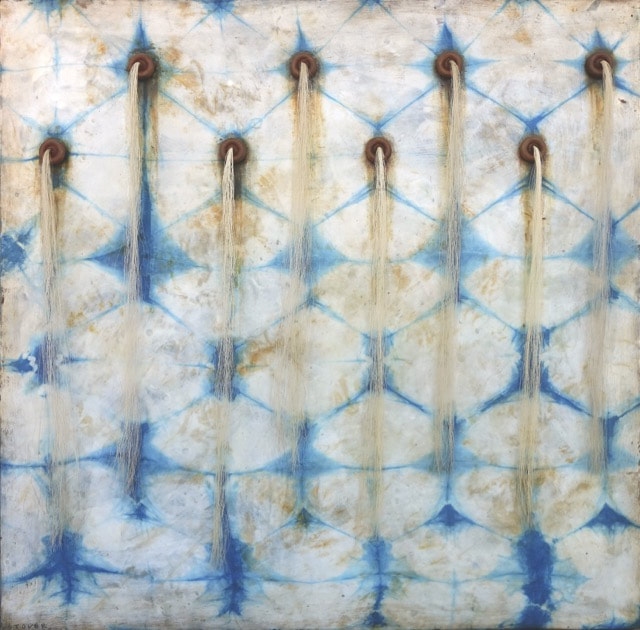

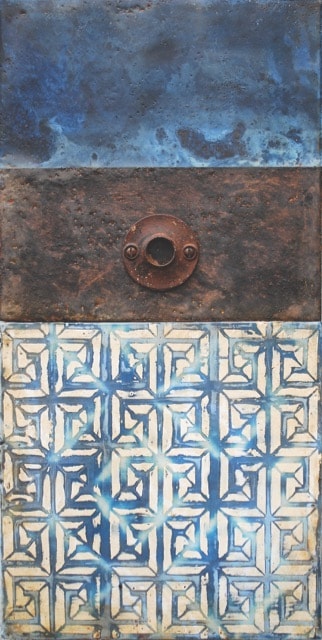

Read about how my adventure in Sardinia led to a new exciting tour: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/celebrating-sardinia/ Find out more about the tour at: Celebrating Sardinia (click on the tabs below the introduction to see all the details) Guest blog by Susan Stover, artist and educator On the eve of the Tastes & Textiles tour, I’m posting Susan Stover’s insights about the power of travel to invigorate one’s creativity. (All photos by Susan Stover.) Travel can greatly impact an artist’s work. It can influence, be a catalyst for change, or further catapult the journey already started. In the absence of familiar surroundings, it can magnify what captures the eye and the emotions. All is new, exciting, and exhilarating. Both making art and traveling have opened up new experiences and challenged me in unique ways. There is so much to be inspired by—the atmosphere in the landscape, hues and textures of a traditional market, shrines and temples, and environments of living and creating. I recently returned from my second trip to Indonesia in the last 15 months. As the experiences and inspirations linger in my subconscious, they continue to influence my artwork. My love of textiles was rekindled as a result of these travels. Fabrics abundantly adorn shrines and temples, are used as offerings, typify ceremonial dress, and are displayed as consumer goods. I am inspired not only by the beauty of the fabrics, but also how they function in a society where art, life, and spirituality are all connected. Nowhere is this more evident than in Bali. Concepts of duality, animism, and the desire for harmony between the natural and supernatural worlds are the foundation of Balinese beliefs. My fascination with the connection of art and spirit lies in the mystery, the unanswered questions, the quest for balance and purpose, the desire for connectedness with others and with the sacred, however they choose to define it. Textiles embody these concerns, which are more evident in cultures other than my own. When traveling, I am conscious of how closely tradition and technology are related. Weaving and dyeing cloth are technologies that have existed for millennia. As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the western world is more removed from these technologies, as most cloth is made in factories. Our direct relationship to the production of fabric and items for survival does not exist. In countries like Indonesia, these traditions are part of cultural identity and there is a sense of pride in the hand making of them. Some of the places in Java and Bali that I visited still produce cloth exactly as it has been done for hundreds of years. The tools and settings of these shops look like they have not changed over the ages, and it was like stepping back in time. It was always surprising to see cell phones in these environments—the juxtaposition of ancient and modern. This is what I am after in my own work—taking something from one arena, bridging the gaps of time and place, and situating it in a new venue. There is an inherent beauty to the handmade, purposed item that looks old and worn. Often I think of history, what or who came before me, what was left behind, and how we are joined to others by the same activities that keep our hands busy. The rhythmic beating of a loom and the repetitive movements of stitching and stamping can be meditative and calming. There is a satisfaction to this type of labor. Textiles imply an association with human touch and human interaction and I am curious how the maker’s role functions individually and collectively in a community. What interests me is the information that textiles contain, as patterns and techniques encode knowledge from ancestors and tell us much about a culture’s cosmology and development. Perhaps it is my own desire for connection to the larger world that drives me to seek out authentic artisans working in methods that have been handed down from one generation to another. Throughout the years, my work has incorporated the combination of textiles and painting. I have worked in many ways using dye, paint, thread, fabric, and fiber. Prior to traveling to Indonesia, I had been using surface design techniques on silk and embedding them into encaustic to develop my own visual language of unique mark-making and patterning. A shift happened in the work as a result of traveling—the fabric itself became the subject matter and a springboard for new content. I wanted to make work that looked like old cloths that were worn in a way that would suggest some sort of use or purpose. They could be fragments or relics and could incorporate techniques typically found in ritual textiles and costumes. Recently, I have been combining surface design techniques (such as discharge, silk painting, and indigo dyeing) on silk with encaustic on panel. There is marvelous allure of adding color to cloth and a magical alchemy of dyeing with indigo. When layering the silk into encaustic, the wax is beautifully absorbed by the silk. The silk then becomes semi-transparent, revealing rich subtleties of colored wax underneath. Murky layers of wax on top of the silk can add depth, mystery, and freeze the fabric in the moment. Working with encaustic in many ways is like working with fiber. There is a tactile quality to the wax that makes one want to touch it. The translucent layers of wax are similar to working with layers of dye. Wax can reflect and absorb light like various fibers. There are the textural and sculptural capabilities of wax as there are with fibers. When I started thinking of my “paintings” as “objects,” it stimulated ideas of working sculpturally and freed me from thinking within the confines of the panel. It opened up the possibilities of working with other fibers, materials, and techniques. Incorporating these materials and working in this way, my intention is to create artwork that evokes a sense of transcendent mystery and purpose. The goal is to imbue the work with a vulnerability and vitality that reflects the presence of the maker. Each piece is a personal meditation on what connects the past and present, the beauty of imperfection and age. The challenge is how to make the things that inspire me and at the same time place them in a contemporary context. How do I celebrate these inspirations, use these traditions, and express it in a way that is relative to my own culture? As I travel and seek inspiration, I am aware of how tourism and commercialism affect these places. Traditional weaving patterns can be found printed cheaply on cotton fabric. ”Fake” batiks are abundant. Natural dyes and materials are often replaced by cheaper synthetic ones. Symbolic meanings are in danger of being lost as techniques and knowledge may not be handed down to future generations. I believe that it is important to recognize the value and conservation of traditions and cultures with awareness and mindfulness of our impact on them. Threads of Life and the Bebali Foundation in Ubud, Bali, seek to preserve and restore indigenous textile cultures in Indonesia. They work with women’s weaving cooperatives to help manage their resources sustainably and relieve poverty in remote areas. The Bebali Foundation does botanical research of natural dyes and mordants. I spent a wonderful afternoon in the Bebali Natural Dye Garden dyeing with the indigo that is grown there. The garden beds are filled with different varieties of indigo and plants for other colors and mordants. My consciousness and respect has grown for the beauty existing in other parts of the world as a result of my travels. I am grateful for the rich heritages that endure and am optimistic of how they might evolve. I am looking forward to future art inspiring journeys in Italy, India and a return to Java with others who share a similar interest in appreciating the artistry of cultural traditions.

Susan Stover teaches and shows her work nationally and internationally and maintains a full time studio practice in Graton, CA: www.susanstover.com. This article first appeared in the Surface Design Journal Winter 2015/2016 “Wax & Fiber” issue, Volume 39, Number 4. The Journal is available in single print issues for purchase at: www.surfacedesign.org/marketplace . A subscription to the quarterly Surface Design Journal is just one of many enriching textile-arts and education benefits enjoyed by members of Surface Design Association, which will celebrate its 40th anniversary next year. Members receive the beautiful print publication 4 times a year along with access to all of our digital editions (published since the Spring 2015 “Warp Speed” issue, Volume 39, Number 2). www.surfacedesign.org/subpage/digital-edition-now-available Feasting is a way of celebrating special events, and many festivals have acquired a constellation of typical dishes. Often these are elaborations of everyday food, tarted up for the occasion. In many parts of Italy (maybe all, but I haven’t been everywhere) no meal is complete without bread, so what better food to make a fuss of. The Garfagnana has its own special Easter bread called pasimata. Paolo Magazzini, the village baker at Petrognola to whom I take my guests for bread lessons, recounted his procedure, the lengthy traditional way. You take flour, sugar, butter, eggs, milk and lievito madre (starter dough). Day 1 morning: mix all ingredients. 12 hours later: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. Day 2 morning: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. 12 hours later: add sultanas, aniseed, vin santo (sweet Tuscan dessert wine), chestnut-flavoured liqueur. Day 3 morning: light wood-fired oven. Bake a batch of bread. Put pasimata dough in round tins. After one hour, take bread out. Oven will be exactly the right temperature for pasimata. Bake pasimata for 40 minutes. Remove from oven and eat enthusiastically. The long rise over 48 hours allows time for the development of exceptional flavours and aromas. Today many people make a ‘fast cake’ version in an hour by substituting baking powder for sourdough starter. Next Easter I’m going to organise a blind tasting of the slow and fast versions.

I didn’t ask Paolo for the quantity of each ingredient, since I can get my fix from him. For those not so lucky, here’s a similar recipe from Castiglione in Garfagnana, a walled town which during the Renaissance was batted back and forth like a ping-pong ball between Lucca and Modena. Perhaps they consoled themselves between battles by eating pasimata. I’ve long wondered how to incorporate the rich agricultural heritage of the Lucca plain into a tour. Watching a bean stalk grow would try the patience even of a very slow traveller. On Thursday I visited the organic farm Favilla in the suburbs of Lucca, where I was welcomed by Andrea, the owner’s son. As he spoke about his farm and its crops, the words tumbled out of his mouth and his face was alive with the enthusiasm he and his family devote to their project. The list of crops is long leaving no season without its fruits: wheat, vegetables and fruit. To find out more about the small group tour germinating at Sapori e Saperi Adventures, read the rest of my blog at http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/a-tour-sprouts/. Read to the bottom of the blog and you’ll find a special offer.

Save the dates: 2–9 July 2017. The Garfagnana and Media Valle del Serchio (Middle Valley of the Serchio River) is my home and the base for many of Sapori e Saperi’s tours. If you’ve been here with me, you might remember that the Serchio is the third longest river in Tuscany. Wild, rugged mountains ascend on both sides of its valley, their rocky ledges bearing stone villages and cultivated terraces. (Although something is wrong with the sound, the pictures say it all.) It seems improbable that so many riches lie hidden in my Garfagnana. It’s the legendary pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. I feel fortunate to have landed here by chance. The people are full of pride and determination to carry forward their traditions. They hope you’ll come share their Tuscany with them.

(Note: Farro IGP della Garfagnana is Triticum dicoccum or emmer in English, not spelt which is Triticum spelta. Emmer is an ancestor of spelt. I was finding emmer on Neolithic sites in Italy when I was an archaeologist on the Early History of Agriculture Project at Cambridge University.) On 23 December as I looked over my menu for Christmas lunch, I was struck by the generosity of my Italian friends and producers. I realised I didn’t have to buy most of the ingredients I needed! They were gifts people had thrust upon me over the last two or three months, not just Christmas presents, but as part of their culture of giving. You share what you have, especially what you make yourself. To find out the story behind the gifts read my new blog over at Slow Travel Tours: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/generosity/

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed