|

It’s a bumper year for tomatoes. We have many such years here in Casabasciana. I often hear my neighbours lamenting that their husbands planted too many plants and they can’t face making another batch of passata. But this year, the glut is universal. A friend in England sent me this photo of his prize specimen. A friend in Quebec has so many this year that he phoned specially to find out what I do with mine. Here’s what I told him. I make passata di pomodoro, a puree of tomato pulp, which you bottle (can) or freeze and use for making more complicated dishes, especially in winter when there are no decent fresh tomatoes (hothouse tomatoes are too disappointing to waste money on). As with all traditional recipes there are many versions. I make the simplest, pure tomato, which I learned from Alessandra Bandoni of Toscaneggiando who does cooking lessons for me. Time: 2.5 hours (with two people working) Equipment 2 or 3 capacious pots (to cook tomatoes and boil jars) sieve (to drain cooked tomatoes) bowl or pot (to put under the sieve) slotted spoon ladle Passatutto Master (to puree tomatoes) 2 shallow bowls (to fit under the 2 outlets of the Passatutto) 14 250 ml / 8.5 oz clean jars and new lids a wee, tiny brush to clean the interstices of the Passatutto The Passatutto Master is essential. It not only purees the tomatoes, it removes the skins and seeds and spits them out to the side, while directing the puree out the front. Life is too short to do this by hand. It isn’t very expensive and doesn’t require electricity; you crank it by hand. I think it’s available everywhere. I wish I had a commission for every time I’ve recommended it! Ingredients 7 kg / 15 lb 8 oz tomatoes (best varieties are fleshy, not watery) The quantity isn’t important, but while you’re messing up the kitchen, you may as well do more rather than less. Procedure Wash the tomatoes and divide them among your pots. Do NOT skin them first. Do NOT add anything else: no salt, no herbs, no water. If you use only tomatoes, your puree will be suitable for any other recipe requiring tomato, and you can add seasonings to suit the dish. Cover the pots and place on burner at medium-low heat. Check frequently to make sure they’re not burning on the bottom. When liquid starts to come out of the tomatoes, raise the heat to medium-high. Meanwhile, assemble the Passatutto and stick with the crank sticking out over the edge of your worktop or table (so you can turn it). It sticks to the table by the suction cup on its foot. To help it stick, dampen the table (it also helps to hold the machine down while you crank it). It will leak a little from below the handle, so put a cloth or sponge on the floor beneath to catch the drips. As soon as the tomato skins split (the liquid will probably be level with the tomatoes), turn off the burner and move the pot to the table. With a slotted spoon move the tomatoes to a sieve set over a bowl or another pot. Let them drain for a couple of minutes (you want your passata to be thick, not watery). Tip them into the top of the Passatutto, turn the crank and watch as the skins and seeds are magically separated from the pulp. Fill the jars with the pulp. The jars should be filled to within 1 cm (1/2 in) of the top. Screw the lid on. Continue until all the tomatoes have been processed. Then put the skins and seed through the Passatutto again (and even a third time if you like). You’ll get a couple more jars of passata. Place as many jars as fit in one layer in one of your pots and cover with tepid water. The water should be 8 cm / 3 in above the top of the jars. Cover the pot with a lid and place on a high burner. Bring to a full boil. Boil for 20 minutes to sterilise the tomatoes. A couple minutes extra won’t hurt. Turn off the burner and leave the jars to cool in the water. Do the washing up. The Passatutto comes apart to make it easy to wash, but you’ll need this little brush (which doesn’t come with it) to get into some of the tiny crevices. The first time I didn’t know, and when I went to use the machine the next year, the inner cylinder was mouldy. As the jars cool a vacuum will be created in the jar and the lid will become concave. If any are not concave by the time the water is cool, you may not have filled the jar full enough, or tightened the lid too hard or not enough, or the lid may be defective. You can diagnose the problem, remedy it and re-sterilise, but if it’s only one or two jars, it’s easier to freeze the passata. Label the jars and admire your passata. When you open a jar in mid-winter, the scent of summer will waft through your kitchen. If you’ve landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here.

0 Comments

Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

‘Relax!’ is a command to me as a tour organiser and to you as a traveller. There’s no way you can see everything, so we may as well leave time to rest, absorb and enjoy. My favourite way to wind down is to go to a village festival, called a sagra. It’s impossible not to relax, while at the same time soaking in the local culture.

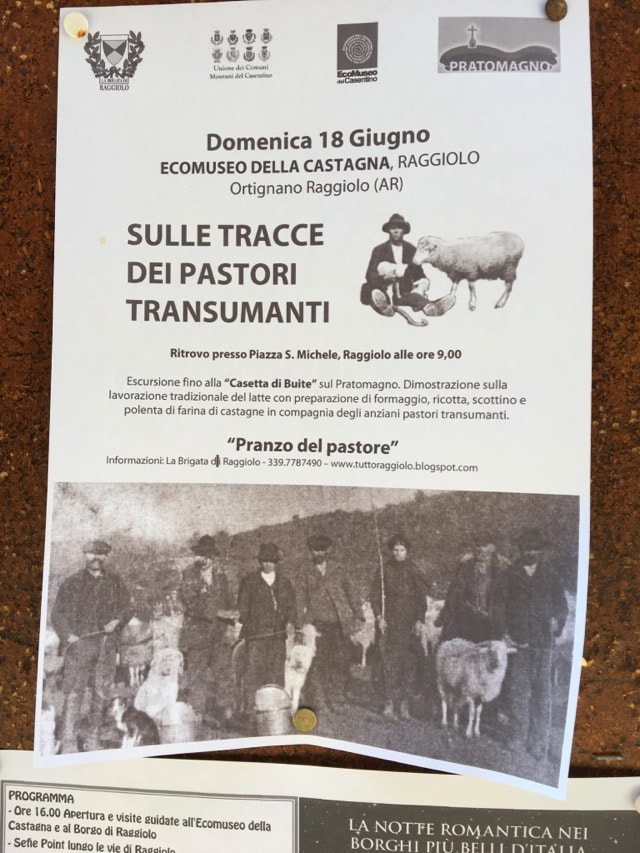

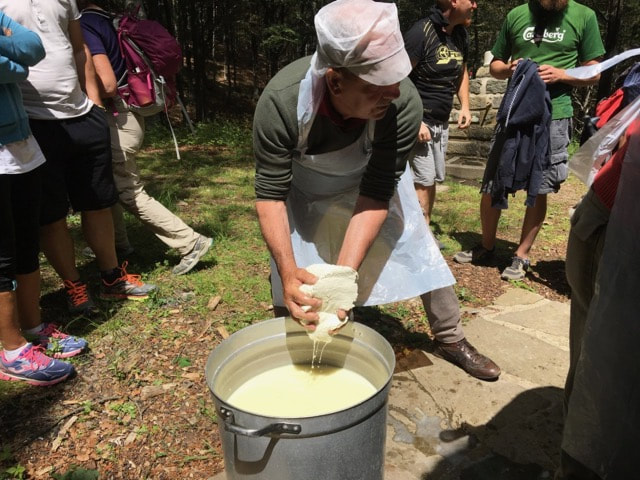

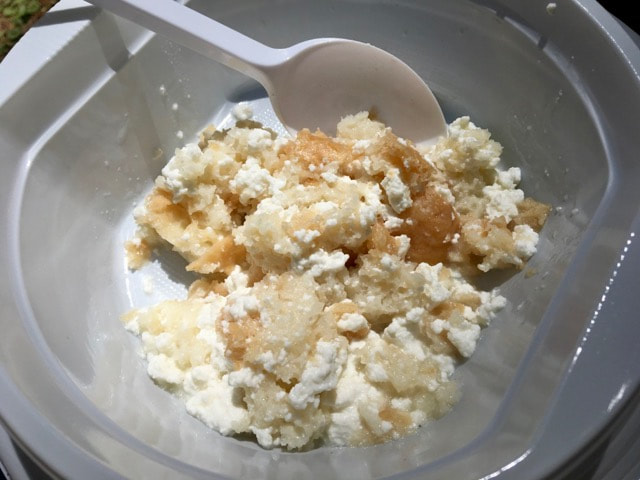

The village of Cascio is top of my list for an experience without deadlines. I’ve already written about its wood-fired oven sagra in spring (http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/a-feast-from-wood-fired-ovens/). At the end of July and early August the village puts on its equally relaxing Sagra delle Crisciolette. See below for a note about the criscioletta. Right now, we’re going to the sagra. Just click here to take you to the Slow Travel Tours website for your anti-stress therapy (and to find out what a criscioletta is): http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/relax/ This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html Feasting is a way of celebrating special events, and many festivals have acquired a constellation of typical dishes. Often these are elaborations of everyday food, tarted up for the occasion. In many parts of Italy (maybe all, but I haven’t been everywhere) no meal is complete without bread, so what better food to make a fuss of. The Garfagnana has its own special Easter bread called pasimata. Paolo Magazzini, the village baker at Petrognola to whom I take my guests for bread lessons, recounted his procedure, the lengthy traditional way. You take flour, sugar, butter, eggs, milk and lievito madre (starter dough). Day 1 morning: mix all ingredients. 12 hours later: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. Day 2 morning: add more of the same ingredients except the starter dough. 12 hours later: add sultanas, aniseed, vin santo (sweet Tuscan dessert wine), chestnut-flavoured liqueur. Day 3 morning: light wood-fired oven. Bake a batch of bread. Put pasimata dough in round tins. After one hour, take bread out. Oven will be exactly the right temperature for pasimata. Bake pasimata for 40 minutes. Remove from oven and eat enthusiastically. The long rise over 48 hours allows time for the development of exceptional flavours and aromas. Today many people make a ‘fast cake’ version in an hour by substituting baking powder for sourdough starter. Next Easter I’m going to organise a blind tasting of the slow and fast versions.

I didn’t ask Paolo for the quantity of each ingredient, since I can get my fix from him. For those not so lucky, here’s a similar recipe from Castiglione in Garfagnana, a walled town which during the Renaissance was batted back and forth like a ping-pong ball between Lucca and Modena. Perhaps they consoled themselves between battles by eating pasimata. In England when I used to prepare historical feasts for Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music, I pined futilely for a cardoon farmer. Cardoons cropped up regularly in recipes of the 17th and 18th centuries. I finally persuaded a friend to grow them on his allotment, but he planted them next to his artichokes, which are nearly identical, and couldn’t remember which was which. In culinary terms it matters; you eat the flower of an artichoke, but the stem of a cardoon. I can’t find any advice on what would happen if you ate the stem of an artichoke, and I didn’t try. Cardoons are common in Italian shops and markets from November to February. Although they are completely unrelated, they look like giant celery but surprise with a flavour of artichoke hearts. The heads come in two shapes, depending on how they’re grown: straight stalks which are called cardi, and curved ones called gobbi. Gobbo means ‘hunchback’, and touching an amulet of a gobbo is said to bring good fortune. Whichever the shape, the cultivation and preparation of cardoons is fiddly. During their last month in the field, the stems are blanched like celery, by piling up the earth or tying straw or paper around them so they lose their chlorophyl and become creamy white. If you’re growing them gobbo-style, you bend them in half before covering them with soil. In the kitchen you de-string them, cut them into chunks and boil them in acidulated water to keep them from rusting. They’re good eaten hot simply with a drizzle of this year’s extra-virgin olive oil. In the Abruzzo a traditional Christmas lunch begins with a soup of cardoons and meatballs. I’ve recently tried a Lucchese recipe for using up leftover bollito (boiled beef): infuse olive oil with garlic and sage leaves over a low heat, add chunks of boiled cardoons and sauté until they start to brown, add the boiled beef cut into cubes, stir well, deglaze the pan with white wine, add a few tinned tomatoes (not tasteless winter tomatoes) and simmer for 15 minutes. As long as you go light on the tomatoes, the flavours balance each other perfectly. Nutritionally cardoons are star players. They are said to have a fortifying and bracing effect on the stomach, protect the liver, reduce cholesterol and blood sugar levels. Who knows, maybe they’re the elixir of youth.

There’s an old variety called cardo gobbo of Nizza Monferrato from the province of Asti in Piedmont. Being on the brink of disappearance, Slow Food has recognised it as a presidium. It grows on sandy soil with no fertilisers, chemical treatments or irrigation. Sown in May, by September the tall luxuriant stalks are ready to be bent over and covered with soil. The Slow Food website describes the plant dramatically attempting to liberate itself to get to the light. In the process of its struggles, it swells up and turns pure white. Once harvested and cleaned, it’s the only cardoon that can be eaten raw, and is an indispensable ingredient of bagna cauda, the typical Piemontese warm sauce based on garlic, extra-virgin olive oil and anchovies. Continuing the purple prose, ‘It’s not merely a dish but a convivial ritual. Simmering in the centre of the table in an earthware terrine, the diners dip the pieces of vegetable and bring them to their mouths, catching the oil on a chunk of bread.’ If you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Nizza Monferrato right now. Postscript: Some ingredients draw me to repeated research. I had written this piece before discovering that I also wrote about cardoons in January 2013: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/seasonal-eating-4-cardoons-2/ Just back from my annual visit to family and friends in Los Angeles, Costa Mesa and Santa Barbara. It was a foodie time. Not least because my sister Gai Klass, before she retired, was top caterer in LA (according to me and the Zagat Guide); my 3-year-old great-nephews are following in the family tradition; my friends in Costa Mesa came on my Advanced Salumi Course last year and are ace picklers, aficionados of Mexican cuisine and blossoming norcini(curers of pork); my friend in Santa Barbara is a private chef (who did a personalised tour with me several years ago); and the rest are great cooks and lovers of good food. I report the latest trends. Armies of pigs have invaded delis, restaurants and antique shops. Everywhere I went pork, from ears to ribs to tails, was on the menu. As expected wine held sway even in the loos in the Santa Ynez Valley, best known for its Pinot Noir. But craft beer was running a close second (as it does now in Italy)… …and came first on Main St, Venice (CA) …and in Carpinteria. Sardinians on Main St, Santa Monica, produce one of Italy’s best exports. And everyone was getting on the buy local and gluten-free band-wagons. In case you’re in the area, I’m sure they’d all love to see you:

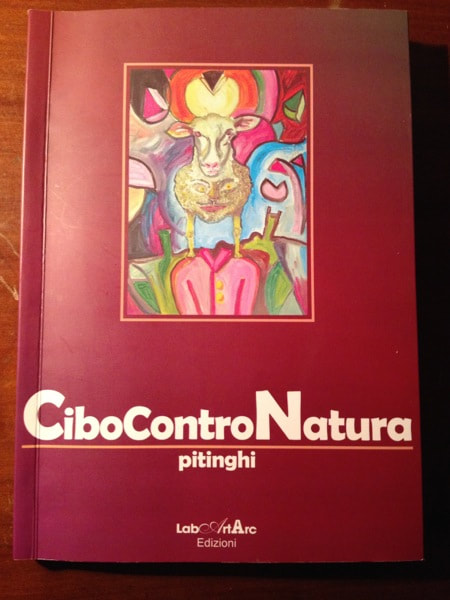

Bacon & Brine, Solvang http://www.baconandbrine.com/ Angels Antiques, 4846 Carpinteria Avenue, Carpinteria, DolceNero, 2400 Main Street, Santa Monica http://www.dolcenerogelato.com/ For a dinner that was so good that I forgot to take a photo: Barbareño, 205 W Cañon Perdido Street, Santa Barbara http://barbareno.com/ PS The next generation gets a head start in the kitchen. The first year I went to the International Truffle Fair at San Miniato one of the sideshows was a small bookstall. A woman thrust a book into my hands and explained exasperatedly, as she touched a finger to her head, that it had been written by her loopy husband. Perhaps he had insisted she listen as he declaimed each of its 121 pages. As I read the polemical Cibo Contro Natura (Unnatural Food) I could hear Signor Pitinghi shouting his manifesto while gesticulating with his hands. The flowery language can be over the top, but far from being mad, it’s full of insights into a passing Italian food culture. This is a frustrated man with the memory of a flavour in his mouth which he finds harder and harder to reproduce in the kitchen. Perhaps his wife is a bad cook, but this isn’t what he laments. He’s dismayed by the swamping of natural food by industrial food, of slow food by fast food, of real cooking by virtual cooking, of found ingredients by packaged and marketed products. Having read a chapter or two, the book itself got swamped by other literature I picked up at other food fairs and only re-emerged recently. My experience of Italian culture, not to mention my comprehension of the Italian language, has grown in the intervening years and many of Signor Pitinghi’s ideas set me thinking and exploring half-trodden paths. Among his many provocative statements is the chapter title ‘Bisogna provare a cucinare o almeno…a cuocere’, which translates literally: ‘It is necessary to try to cook or at least…to cook’. The dilemma for me is one of linguistics and culture; for him it’s one of action. I check my excellent Italian-English dictionary by Ragazzini and Biagi just to make sure both cucinareand cuocere mean ‘to cook’. They do, but there’s a hint of a difference. Cucinare can also mean ‘to do the cooking’. My Italian friends sometimes correct me for using one or the other incorrectly, but I haven’t quite got it yet. Back in San Miniato having lunch with Riccardo and Amanda, my truffle hunter and his wife, I ask them if they can enlighten me. We’re eating a typical Tuscan lunch, a simple roast chicken with potatoes and onions. Amanda explains that if she had bunged the chicken into a roasting pan and stuck it in the oven until it was done, that would be cuocere. Instead, she had seasoned the chicken, browned it in olive oil, deglazed the pan with white wine, put it in the oven and basted it from time to time. She’d cut up the potatoes and onions and added them to the roasting pan to cook and become glazed by the juices of the chicken. All very simple yet this is cucinare. Now I could transfer it to my own culture: ‘I can boil an egg, but I can’t cook’. Pitinghi reminds his Tuscan readers how simple their cuisine is and muses on whether in our ‘global village’, with mother at work and incessant television cooking programmes interleaved with adverts for snacks full of preservatives and breaded fish fingers ready for frying, the family no longer knows how to keep traditions alive, especially those of cooking and local food. He ends with this exhortation ‘to all of us: “let’s try to cucinare!” or at least, if this verb seems too challenging “let’s try at least to cuocere something”.’

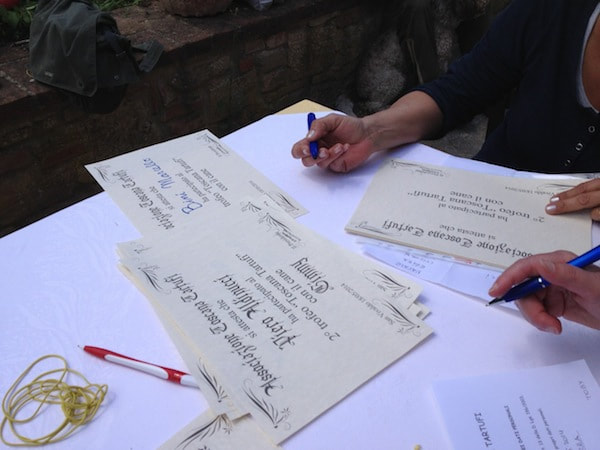

I’m just back from the second annual Tuscan truffle hound competition organised by Riccardo, my truffle hunter. The competition is about as exciting as a village cricket match without the beer tent. Very little happens, but it does have the merit of being easy to understand the rules, unlike cricket (at least for me). I used to listen occasionally to a cricket match on the radio enjoying the foreign language of the commentators. Truffle hunters also have their own language which seems to consist of one- or two-syllable utterances to which the dogs rarely listen. This video gives you some idea of the pace and mutterings. [vimeo]https://vimeo.com/95670529[/vimeo] If it’s not much of a spectator sport, at least it demonstrates the method used and patience needed to train a dog to be a good truffle hound. There are very few breeds that can’t excel, but you have to start the training when they’re just a few weeks old. Give them simple commands, teach them to retrieve a stick and eventually bury a plastic capsule with a fragment of truffle in it for the puppy to find—over and over and over again. Riccardo explains the psychology of training: dogs are pack animals and the man (I haven’t met a female truffle hunter yet) has to play the role of leader of the pack. Some men don’t have it in them. Others have figured out how to motivate their dogs to keep their noses to the ground. Riccardo and Teo demonstrate best form. Note his subtle hand movements. While not exactly electrifying, the location is beautiful and the camaraderie enjoyable. What better way to spend a sunny Sunday than chatting to friends while sitting on a stone wall in the shade of a pergola at San Vivaldo monastery. When the trials are finished, all the dogs and owners converge on the ring to retrieve the buried capsules. At this point a Franciscan friar emerges and surveys the scene. He gazes at the small square marked out on the lawn, shakes his head and states that surely in so small a space every dog would find every truffle. Meanwhile, the certificates are being prepared and the prize-giving begins. In 15th place, the man whose dog found none. No one’s a loser. In first place, a man no one knows. He wants to be notified of the next contest, but doesn’t understand what an email address is. What sets a Tuscan truffle hound competition apart from a cricket match is lunch. We drift into Il Focolare (‘the hearth’), a restaurant in the cellars of one wing of the monastery, for an abundant and well-cooked lunch. Riccardo and I have taken many guests on real truffle hunts (no plastic capsules) followed by a truffle lunch at Riccardo’s home (click November, but you can hunt truffles in almost any month). We’ve also designed an intensive truffle course, and soon we’ll have a truffle weekend on offer as well. Let me know if you’d like to be notified when it’s ready: [email protected].

After a full Italian lunch, I crave something fresh, light and pure. I stop at Patrizia’s fruttivendola in Villa (Bagni di Lucca) and buy a sack of new season peas in the pod. I love popping open the pods and detaching the peas with one swipe of my thumb. It can be a social activity too; children really get into it. I can’t resist popping a few raw ones into my mouth as I work. They’re so tender and sweet. One minute in boiling salted water and my dinner is ready. No butter, no ham, no spring onions, just a plate of peas. They melt in my mouth. You don’t have to have lofty ideals of saving the planet to eat locally and seasonally. You can do it as a totally selfish act to pamper yourself. To me it’s better than a massage.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed