|

By Alison Goldberger When I wanted to learn how to make salami I knew travelling to Italy was the only way to do it, so I booked onto the Advanced Salumi Course in Tuscany with Sapori & Saperi Adventures. The course was incredible, and I learned so much. I was also so impressed by Erica and her company that I asked her if we could collaborate. I’m a Scottish journalist and organic pig farmer but have lived and worked in Austria since 2015. Now I assist Erica with social media and online marketing. I absolutely love telling people about my time on her course and now I am excited to share with you why I think travelling with a local expert in 2022 (and beyond) can only enhance your holiday experience! Eat in incredible restaurants...and in private homes One of the most wonderful experiences I had was to dine in restaurants uncovered by Erica after years of eating and living in Tuscany. You can be guaranteed you’re not just eating in the restaurant all the other tourists found online! We were treated to dinner at Il Vecchio Mulino, where Andrea brought out course after course of exquisite local food. Many of Erica’s courses and tours also include meals in private homes. In Capezzano I was welcomed into Gabriella’s home where I ate the best seafood I’ve ever had. The freshest seafood cooked to perfection and an extremely warm welcome – it was an unforgettable experience. Learn how to make prosciutto as the artisans do Do you have a passion for prosciutto like I do? It’s unlikely you can just stroll up to any producer and they’ll tell you how it’s done. But when you travel with a local you certainly can, and they are happy to answer all your questions. When learning all about salumi in Tuscany I visited numerous artisans and gleaned the knowledge they’ve garnered over a lifetime. On these tours you’re also supporting these very small businesses, creating wonderful slow food with a passion you’re unlikely to find in large-scale producers. What’s more, you get to taste their incredible products! Savour products from small-scale producers You want to visit a local organic olive oil producer, or have always wondered how chestnut flour is produced, or perhaps gelato is more your thing? These were all requests during my course and every one was fulfilled! I took home a bag of chestnut flour after seeing how chestnuts are dried and milled. I sampled the best pistachio gelato at Cremeria Opera in Lucca and bought the tastiest new-season olive oil from Claudio Orsi of Alle Camelie. Erica has built up so many contacts across the region and she is happy to help visitors find what they’re looking for.

Erica drove us during our course so she was always on hand to answer questions and give us explanations about what we were seeing as we travelled. It was information born from a passion for Tuscany and gave us a wonderful insight into the history of the region as well as what it’s really like to live there. This is a feature of all tours and courses from Sapori & Saperi. For instance, on the Tastes & Textiles tours participants learn all about Lucca’s rich tradition of producing textiles. Meeting local craftspeople provides a wealth of knowledge you couldn’t get elsewhere! Did someone mention gelato I know one of my first thoughts when I think of Italy is gelato. We were taken for a quick pit-stop to sample some delicious gelato. It was actually in the Cremeria used for the Art & Science of Gelato course run by Sapori & Saperi. During that course participants immerse themselves in the icy world of Mirko Tognetti of Cremeria Opera Naturali per Gusto, Lucca. They learn his secrets and the science behind gelato and how to create their own flavours. Sounds like an absolute dream to me!

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 20 January, 2019.

0 Comments

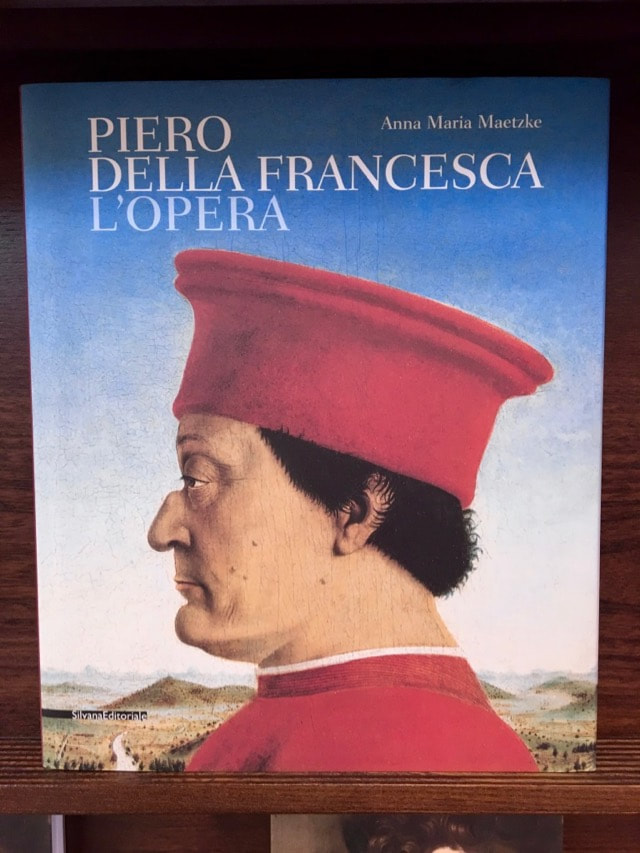

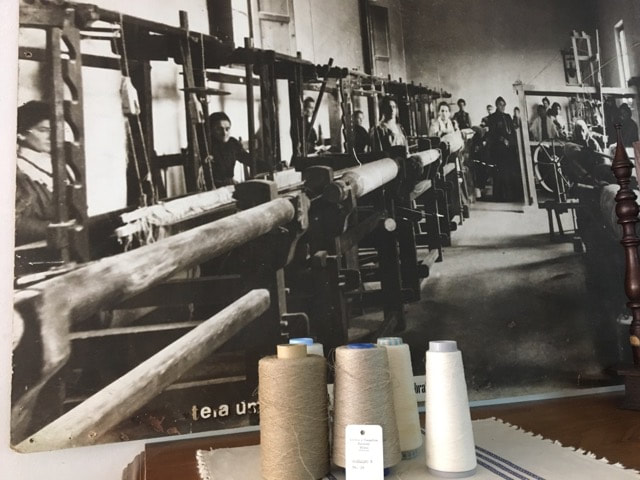

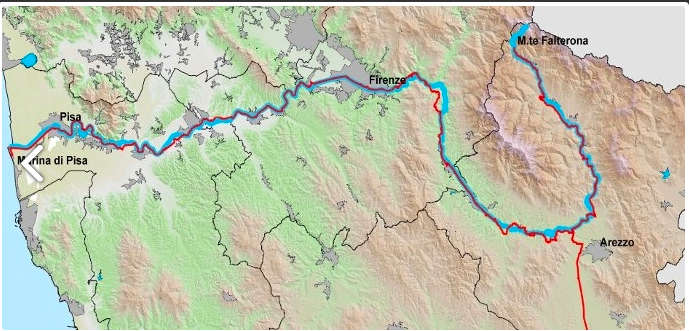

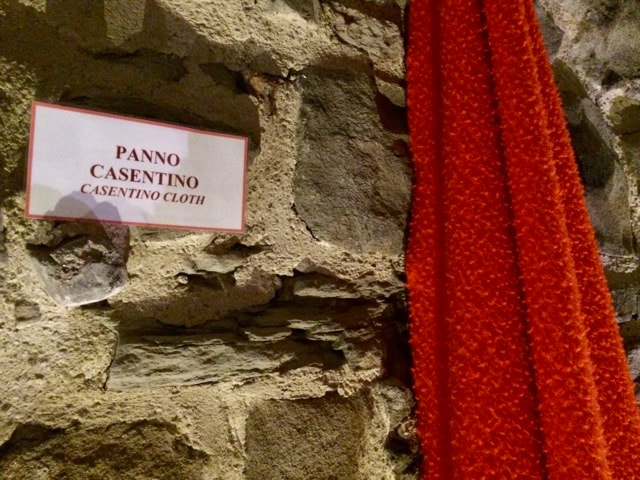

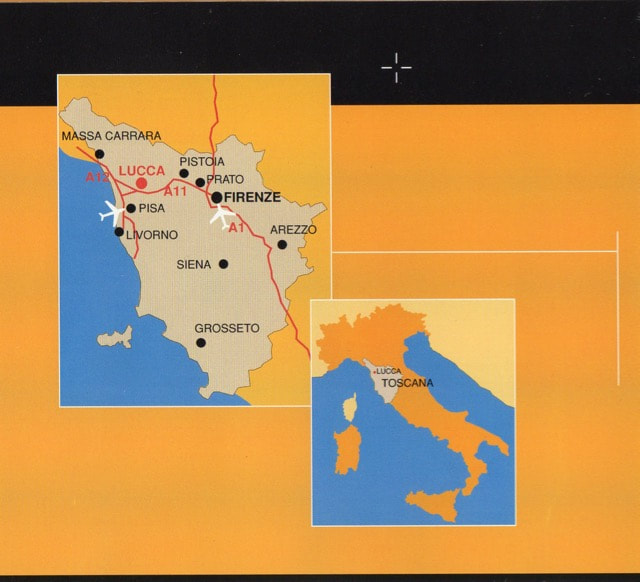

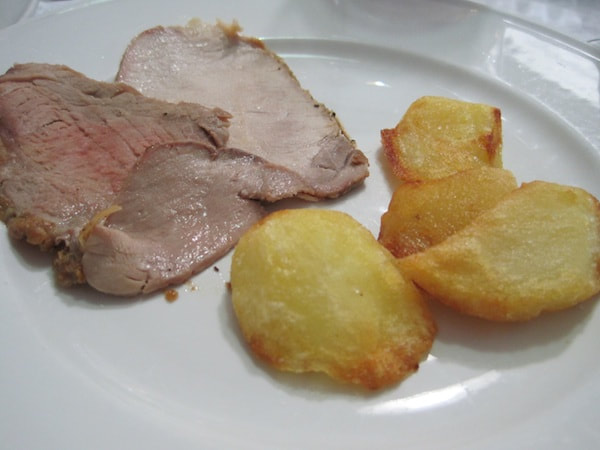

Another tour that didn't take place due to the coronavirus. Since many of you enjoyed the virtual Celebrating Sardinia tour and the Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I’m going to lead you on a virtual Woad & Wool tour. Arm yourself with a cup of coffee or a glass of wine and enjoy the journey. Since my tours take you far away from the well-trodden tourist routes, a couple of maps will help you get your bearings. Saturday 16 May 2020 You’ve already arrived at Arezzo, a beautiful little town in southeastern Tuscany. I advise arriving a day or two before the tour so you can get to know it. There are many things to enjoy, and I only take you to the ones you probably won't find on your own. You’re probably a weaver or spinner or dyer, or maybe you’re interested in beautiful handcrafted objects even though you don’t make them yourself. You definitely like eating good natural food made with local ingredients! Right now we’re having lunch at my favourite restaurant in Arezzo, La Tagliatella, where mamma is in the kitchen, a son is a distinguished sangiovese wine sommelier (Chianti is mostly sangiovese grapes) and I’ve never seen another tourist. I introduce you to my dear friend and co-leader Cheryl Alexander of Italian Excursion, and we’re all talking excitedly as we get to know each other. After lunch we drive east and slightly north, over a mountain pass from Tuscany into the region of Le Marche. Take a good look at the trees. They were felled and floated down the Tiber River to be used as beams for many of the magnificent churches of Rome. We descend to the Metauro River valley and arrive at Oasi San Benedetto, a 9th-century former Benedictine abbey. In the abbey dining room, dinner cooked by the inimitable Patrizia Carlo is super-abundant and anything but plain. The first of our stomach-stretching exercises. Sunday 17 May 2020 Today we get to know the Metauro River valley. Fifteen minutes down the valley is Mercatello sul Metauro. Beatrice Cantucci has organised our morning, which starts with a tour of her mediaeval town. As fascinating as her tour is, it’s the women of the local lacemaking club and the men of the Academia del Padlot who win the day. The women are such good and patient teachers that you manage to make a creditable strip of lace even if you’ve never touched a lace bobbin before. Of equal skill among the pots and pans of the kitchen are the men who cook our lunch in their clubroom over a bar (=pub). They’re delighted when I ask if we can come into the kitchen to watch them at work. I’d be incredibly nervous frying so many eggs, but there’s no better combination than perfectly fried egg and the crispy fried goleta di Mercatello (pork cheek similar to bacon). After lunch some of you might opt to go back to the monastery for a virtual rest, but I wouldn’t advise it because our visit to the Roman house in Sant’Angelo in Vado is too interesting to miss. Unfortunately for the inhabitants, but fortunately for us, in the 6th century AD the Ostrogoths totally destroyed the town and it was completely silted over by the Metauro River. The mosaic floors of the Domus del Mito (House of Myth) are so well preserved that you feel as if the Roman family, who lived here toward the end of the 1st century AD, have gone shopping and will be back soon. Monday 18 May 2020 Today is our virtual woad dyeing workshop with Max, one of the highlights of our virtual Woad & Wool tour. We roll out of bed, grab some breakfast and meet Max next door at his Museum of Natural Colours. The lengthy preparation of blue dye from leaves of the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria) made it affordable only by the aristocracy. One of those was Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, who ruled this part of Le Marche in the 15th century. I’m sure you know this portrait by Piero della Francesca, who we’ll meet later in the tour. He’s depicted in red, but in fact the Montefeltro colours were blue (woad) and gold (reseda or dyer’s weld). I hope this year was a better year for reseda. Since last year was terrible, we used imported annatto instead. Max does lots of workshops with children, and besides the dyeing, you find yourself grinding pigments and painting with them. In the afternoon we join Patrizia in the kitchen for a lesson preparing food of various colours. 'I just got some local violet potatoes’, she says excitedly. ‘Let’s make gnocchi’. And you do. Tuesday 19 May 2020 Sad to say, this morning you must leave the virtual Oasi di San Benedetto, but I promise you that the rest of the virtual Woad & Wool tour will be equally entrancing. We drive from the region of Le Marche back over the mountain pass into Umbria. A friend of mine who studies history obsessively explained to me that Le Marche translates as ’The Marches’ which in mediaeval Europe was a border between realms, in this case three: Tuscany, Umbria and Romagna (now part of Emilia-Romagna). We are touring the orchards at the Archeologia Arborea (Arboreal Archaeology) with the inspirational Isabella dalla Ragione. With her father she started salvaging ancient local fruit varieties, many dating back at least to the 15th century. She studies their representations in paintings and books and has discovered recipes for how they were used. There are so many more interesting facets to Isabella’s life that I can’t tell you everything in this small space. A good reason to come on the real tour in May 2021. It’s a 10-minute drive into Città di Castello where we have lunch at Trattoria Lea, take a quick look around the town and meet at Tela Umbra a Mano for a private tour of the linen mill and its museum. Can you believe, they are still weaving fine linen sheet-width fabric by hand! Two women sitting next to each other at each 19th-century loom. In the museum you see antique Perugia towels, the blue decoration dyed with woad. Sorry no photos allowed, so you’ll have to come to see them. And there’s a touching love story and a friendship with Maria Montessori, the founder of Montessori schools. We could easily spend more time in this fascinating city, but it’s getting late and we have a half hour drive to our accommodation at Agriturismo Terra di Michelangelo. Wednesday 20 May 2020 Last night our virtual Woad & Wool tour took us to Agriturismo Terra di Michelangelo. Yes, that most famous Renaissance artist was born only 10 minutes from the farm. I’m not taking you there because on my research trip I decided, although they’ve done their best, a simple house is just a house. Instead we’re going to Anghiari to visit the much more exciting Busatti weaving mill. It’s still in the private ownership of the Busatti family, and the first time I went I was privileged to be shown around by Giovanni Busatti himself, who even took us up to the private guest apartment on top floor. Today Michelangelo Formica, head of sales, leads us into the bowels of the building where the 19th-century jacquard looms are clanking away. Michelangelo shares my philosophy about the value of quality. When he’s at an international textile fair, if he’s approached by a buyer asking for his lowest price, Michelangelo replies, ‘I’m not the right supplier for you’. At the end of the tour, you can’t resist buying some of their luscious linens. It’s worth checking the scrap room where you’ll find real bargains. Until you come on the tour in May 2021, you can shop online at here. If any restauranteurs are reading this, Busatti will work with you to create unique table linens for your restaurant. Sorry if this sounds like an advertorial, but I love the people and the establishment. Depending on how long you spend shopping at Busatti (last year Jenny bought fabric for a huge table cloth), you have free time to explore Anghiari and have lunch. I have two favourites. Last year I went to Talozzi Bistro, so today I’m going to the Cantina del Granduca (the Cellar of the Grand Duke). It sounds posh, but don’t forget it’s his cellar where a mother and son preside. You can even get a good salad, which by now you’re really craving. Soon it’s time to meet in the main piazza for the 10-minute drive to Sansepolcro. The early Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca was born here, and we’re going to the Civic Museum to see some of his work. The masterpiece here is his 'Resurrection'. Aldous Huxley called it the greatest painting in the world. This absorbing video gives you an excellent foundation for our visit. After the museum, some of you visit the Aboca Museum of medicinal herbs and others wander through the town. I’m going to the duomo to revisit a painting that makes me laugh. Now we return to our agriturismo to learn how to make the classic Tuscan cantuccini (you probably call them biscotti), which are so good after dinner dunked in vin santo (Tuscan dessert wine). But first a relaxing aperitivo on the terrace. Gabriele serves us the salumi (prosciutto, salami, etc) he makes from his heritage Cinta Senese pigs. Thursday 21 May 2020 Today the virtual Woad & Wool tour heads north into the Casentino. Never heard of it? You’ll know it well by the end of the tour. It’s only an hour’s drive through rolling hills to the mediaeval fortified town of Poppi where we meet Luca Bellugi at the workshop of his late aunt Elisa. She was an accomplished weaver and fashion designer, but is most famous for having woven a blanket for the Pope and curtains for Jacquie Kennedy. It’s lunch time, and I hope by now you have complete trust in me. If not, your heart will sink as we drive onto the forecourt of an Esso station. We enter the small marquee at the side and there before us, as if by magic, is an elegant dining table. Course after elegant course of local food paired with local wines arrive in the hands of the three Marzi brothers and their nephew Francesco. After our virtual gourmet lunch at the Esso station, we’re happy to reach the Castello di Porciano above Stia where we’ll stay until the end of the virtual tour on Monday. Now we’re dining at the water mill Mulin di Bucchio, very near the source of the Arno River, the one that flows under the Ponte Vecchio at Florence and down to the sea at Pisa. You can see its strange route here from top right (near where we’re sitting) running south and hanging a U to go back north to Florence. I don’t know why, but water mills fascinate me. Perhaps it’s the simplicity of the machinery (even I understand how it functions) and the energetic efficiency. Naturally flour is the protagonist of the meal. Friday 22 May 2020 Everyone who wants a virtual morning walk in the sun down the hill from the castle to Stia should leave now. Those going with the driver can relax for another 15 minutes. We arrive at the Museo dell'Arte della Lana (Museum of the Art of Wool) for our tour and weaving workshop with Angela Giordano. The museum is in a woollen mill, a beautiful example of 19th-century industrial architecture. All the machinery was powered by water. It finally closed in 2000 after a steep decline due to competition from synthetic fabrics. The strong, warm rustic wool is called panno casentino. After being woven the fabric is fulled (washing and beating to compact the fibres) and napped (pulling up fibres using hooked needles to create a fuzzy surface). Both processes increase the water resistance and warmth of the fabric, important characteristics in a shepherd's cloak as well as garments intended for an aristocrat's draughty castle. I first heard about the museum when I received an invitation to a temporary fashion exhibition there. Angela leads us in a weaving workshop. Experienced weavers can do monk’s belt weaving, and the rest backstrap weaving. It’s only a 5-minute walk to our restaurant on the old main street of Stia. On our way we step into Pieve Santa Maria Assunta. When you’re in a romanesque church, always look up. The capitals of the columns often depict strange pagan creatures. Filetto restaurant next door presents a short menu of typical Casentino dishes. I’m having acquacotta. It means ‘cooked water’, but is in fact yet another Tuscan dish for using up stale bread. You stew onion, celery and tomatoes in vegetable broth, and at the end of the cooking poach one egg per person right in the pot. After lunch we finish our workshop with Angela, before going next door to Tessilnova. where owner Claudio Grisolini is expecting us. It was his father who popularised panno casentino culminating in Audrey Hepburn wearing a coat made of it in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’. Claudio takes us behind the scenes to a vaulted room which was part of a woad processing mill. It’s been a full day. Time to relax with an aperitivo and dine at Osteria Toscana Twist—local Tuscan ingredients prepared with a modern twist. Saturday 23 May 2020 Virtual yesterday was dedicated to weaving and textiles. Virtual today it’s food. We’re off to visit cheesemaker Lorenzo Cipriani and his pasta wizard mother Miranda. Picture yourself travelling along winding mountain roads and then a dirt track to their sheep farm at the end in the Casentino Forest National Park. It’s a beautiful day, and Lorenzo decides to make cheese outside. In the photo below he’s taking curd from the pot to make raviggiolo. You probably haven’t heard of it, partly because it’s only made in a few places in Tuscany, but mainly because you have to eat it very fresh, within two or three days. Way too short a shelf life for supermarkets! We have it as antipasto for lunch drizzled with Lorenzo’s olive oil. Next out of the cheese pot is pecorino. Lorenzo cuts the curd to allow the whey to come out, then gathers the curd with his hands, lifts it from the whey and puts it in moulds to drain and eventually to age. In the kitchen we gather around Miranda to watch her make tortelli di patate (potato ravioli), a speciality of the Casentino. We don’t make them in my part of Tuscany. To you they might sound like carbohydrate stuffed with carbohydrate, but they’re wonderfully light and flavoursome served with sage butter and grated pecorino. You have a free afternoon on the virtual Woad & Wool tour. Maybe you walk on one of the many paths around the castle or maybe you write emails to family and friends or maybe you relax in the sun. Now we’re at dinner at La Buca in Soci, just down the river from Stia. Last night was your chance for vegetables. Tonight the speciality is tagliata. Tagliata means sliced. In Tuscany it's a thick rib steak, grilled rare and cut vertically into slices. There are other dishes on the menu, but if you like beef, this is the place to have it. They serve it with the most more-ish fried potatoes I’ve ever eaten. Sunday 24 May 2020 I’m so excited about today’s activities on the virtual Woad & Wool tour. I’m taking you to the Osteria da la Franca at Corezzo for a hands-on lesson making the tortello alla lastra and then to the herbal pharmacy and hermitage of the Benedictine Monastery of Camaldoli. Tortello and raviolo are members of the same family: little stuffed pasta pillows (if they end in ‘i’, they’re plural). What you call them depends on where you are and what they’re stuffed with. The tortello of Corezzo is stuffed with potato, similar to the tortello Miranda made for us, but they’re not cooked in boiling water. Instead they’re cooked on a lastra, a slab or sheet or plate, in this case of stone which is heated over an open fire, like a griddle. Owners Daiana and Mattia (and their three young children) welcome us and introduce us to their cook Loredana. She’s a patient teacher and you’re excellent students. Don’t eat too many! Loredana and Mattia have prepared a big lunch for us. As we drive along the mountain road to Camaldoli, are you thinking, ‘Why another Benedictine monastery? We’ve already stayed in one.’ Camaldoli is different. There is still a community of monks and hermits living here. The setting is extraordinary. Not bare and rocky like the nearby and better known Sanctuary La Verna where St Francis is said to have got the stigmata. Here the mountains are lush and wooded, because for centuries the monks planted 4–5,000 fir trees every year, helping prevent global warming before it became critical. We visit the herbal pharmacy at the monastery. The museum is full of fascinating instruments: stills for distilling essences and huge ceramic storage jars. I would have liked to have walked up to the hermitage, but since it’s raining lightly, we drive. We glimpse the hermits’ simple houses through a gate. But it isn’t all austerity, as testified by the interior of the chapel. We take a different route down and pass a clearing full of Eremurus bulbs glowing like candelabras in the misty air. We arrive slightly chilly and damp at the Locanda dei Baroni, opposite the monastery, happy to find a fire burning in the hearth. Monday 25 May 2020 It’s the last day of the virtual Woad & Wool tour and time to leave the castle where Federica, Martha’s righthand woman, has looked after us so well. Don’t be too sad. There’s one more adventure awaiting you at Arezzo. We have a virtual visit to a painting restoration studio. It was recommended to me by the woman who also told me about the wool museum at Stia. Before my first visit in 2017 I had no idea of how you restore ancient paintings. The work is detailed and painstaking, but also exciting. I’ve visited three times and the women, who call themselves Art Angels, have always been working on a polyptych of 13th-century wooden panels painted by Pietro Lorenzetti, the older but less famous brother of Ambrogio, whose 'Allegory of Good and Bad Government' you might have seen in Siena. Marzia shows you the techniques they use to uncover the original painting. The good news is that they finally finished! The opening was scheduled for 17 April, but had to be postponed due to Covid-19. I wonder what they’ll be working on next year. And now it’s time for virtual hugs and kisses (allowed under social distancing rules) before we scatter to further travels and home. If I’ve whetted your appetite for Tastes & Textiles tours, head on over to my Tastes & Textiles web page to find out more. You’ll find dates for tours in 2020 and 2021. There are still places on the Wine to Dye For tour starting on 15 September 2020. If you’re interested, let me know. I’m not requiring a deposit until we’re all more certain about the possibilities for travel this year.

Enea is one of the cheesemakers to whom I take my guests. He lives on a farm at the end of a dirt road that runs along the top of a ridge. At the point where the tarmac runs out, there’s a vineyard. Bumping slowly along the rutted road you pass a house, then nothing for 10 minutes. As the nose of the ridge begins to dip toward the valley, you spy a ramshackle house with solar panels on the roof. If you come in July, you’ll think you’ve arrived at a farm machine museum until you see Enea putting his heritage wheat through the vintage thresher. Enea and his wife Valeria are nearly self-sufficient. They have a herd of goats, two cows, a few chickens, a couple of horses, a vegetable garden, an olive grove and fields of cereals and hay. They’re hoping for another cow. During the spring and summer Enea milks the goats every morning, makes cheese with their milk and then, with the help of his working dogs, takes them out to graze. The dogs are tri-lingual. I don’t think the goats are. On days when we’re there and he doesn’t go out with them in the morning, their complaints are perfectly comprehensible nonetheless. On Wednesdays he makes sourdough bread. His bread shed contains a wood-fired oven and a tiny mill where he grinds enough of his heritage wheat for the week’s batch of bread. On Wednesday evenings he goes to town to deliver his produce to a group of friends who buy collectively They’re self-sufficient for art and music too. Valeria paints and Enea plays the guitar. The solar panels and batteries keep them in touch with the outside world via their cell phones, computer and internet connection. One of the guests in the last group I took there asked Enea why he chose to make cheese. He told us this story: ‘When I finished school, I knew I didn’t want to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I enjoyed helping a friend pick his olives. Then I rented an apartment from a cheesemaker with goats. He was French and made French-style soft goat cheese. I watched him and began to help him. I saw he was always smiling, and I decided that was the life I wanted.’ Enea is one of the cheesemakers who teaches our course Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese. Click here for all the details.

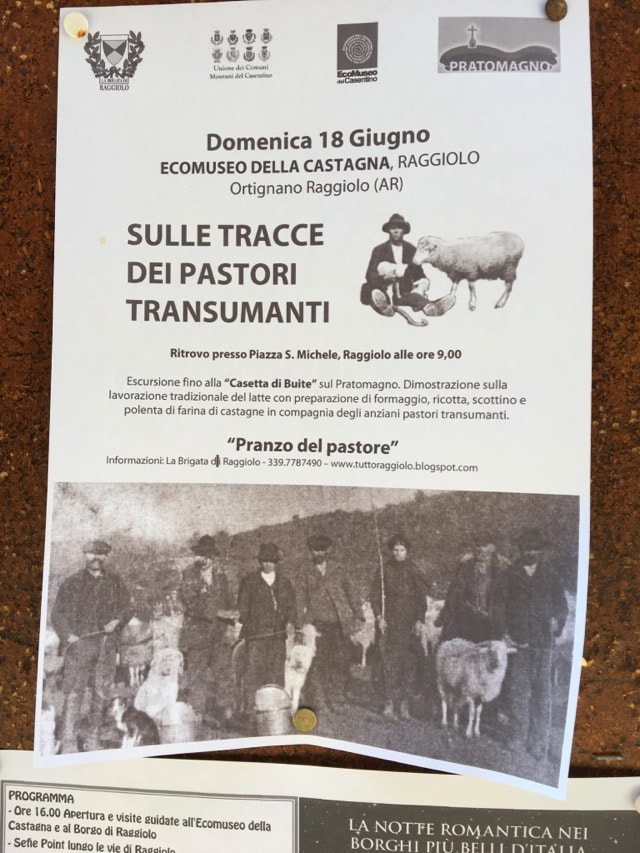

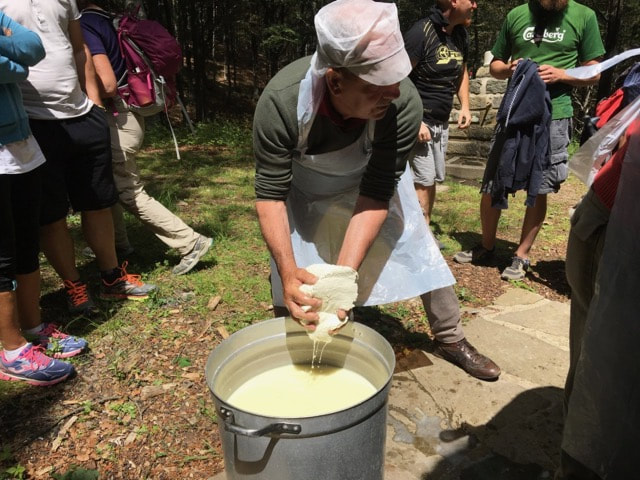

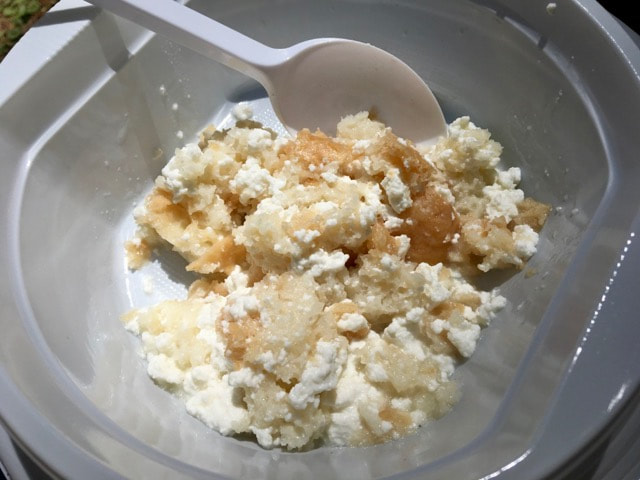

This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html Did you know that olive oil is the only common cooking oil that is the juice of a fruit? All the other oils we use in our kitchen come from seeds: sunflower, rapeseed (canola), peanut and grapeseed. This realisation leads directly to another question. Would you cut an orange, leave it on the counter for a week and then squeeze and drink the juice? Would you step on an apple, leave it on the table for three days and then eat it? Yet that’s what happens to many olives before they’re pressed to extract olive juice. I’ve tasted and written a lot about olive oil, but this idea had completely escaped me until I met Elisabetta Sebastio last year. She’s a professional olive oil taster both for Italian Chambers of Commerce and international olive oil competitions. We ran our first full-day olive oil class during my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November. It was a revelation for all of us.

Learn more on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/olive-juice/ The southwestern corner of Sardinia is called Sulcis. The word derives from the Carthaginian city of Solki. This is just one tiny example of the cultural palimpsest that makes up present-day Sardinia. Before the Carthaginians when the Phoenicians began visiting Sardinia in around 900 BCE, they encountered people of the Nuragic civilisation, which originated in about 1800 BCE. The ruins of their gigantic stone towers and settlements still dot the countryside; 7000 of them remain. Hard on the heels of the Carthaginians, the Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Spaniards, Pisans, Genovese and Piemontese all demanded their turns on the island. It’s no wonder that coming from Italy you feel as if you’ve arrived in a foreign country But it wasn’t the distant past that drew me to Sardinia. Some of the women coming on my September ‘Tastes & Textiles’ tour wanted to visit a woman who weaves with the fibres of the beard of a giant Mediterranean mollusc, and they asked me to take them. Barely credible, I thought, but her workshop had a website which placed it in the town of Sant’Antioco, on the Island of Sant’Antioco in the territory of Sulcis. Here was the ideal excuse to visit Sardinia, which I knew only from its pecorino sardo cheese and Vermentino wine…

Read about how my adventure in Sardinia led to a new exciting tour: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/celebrating-sardinia/ Find out more about the tour at: Celebrating Sardinia (click on the tabs below the introduction to see all the details) My Tuscany isn’t the manicured cypress-lined lanes of Siena and Chianti. It isn’t the great art and architecture of Florence. My Tuscany is Lucca in the northwestern part of the region. As enchanting and perfectly formed as the city of Lucca is, it isn’t my Tuscany either. My Tuscany is the Piana di Lucca, the flat plains and low hills surrounding the city. My Tuscany is Versilia, the coastal plain to the west of the city. My Tuscany is the Media Valle del Serchio and the Garfagnana, the mountains and the Serchio River valley to the north of the city. This is the territory you come to for your adventures with Sapori e Saperi (‘flavours and knowledge’). Some friends have made four short films capturing the essence of my Tuscany. Although they call it Part 2, I’m dishing up Lucca first. If you’ve been on the cheese course (Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/), you’ll recognise Monica Ferrucci and her goat cheese. Or, your feet might have helped Gabriele da Prato crush his grapes. Maybe you’ve attended the Disfida della Zuppa (Soup Tournament) and helped judge the zuppa alla frantoiana entries (read more about the Disfida here: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/better-than-the-winter-olympics/). Or did you pick and press olives with me. If not, treat yourself to my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November (http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/small_group_tours/autumn-in-tuscany/). You’ll have a crash course in olives and their oil, you’ll also hunt for white truffles (and eat them) and, best of all, you’ll get to know a little bit of my irresistible Lucca.

A guest blog by Bob Schroeder Bob, his brother Dick and their friend Cullen Case came on my Advanced Salumi Course. They wanted to make the most of their visit and signed up for a truffle hunt on the Tuesday afternoon after the extension workshop. Bob gave me permission to republish his enthusiastic report to his family and friends back in the States. January 20, 2015 We went truffle hunting today. Lots of fun. Our guide actually trains dogs. He took Guy Fieri of Food Network fame on a hunt. Thanks, Bob!

In case you don’t know, truffles can be found all year long. Although the white Italian and black Périgord truffles are the stars, they’re all good and well worth tasting. We have seven edible ones in Tuscany. After the hunt, we go back to Riccardo’s home for a truffle feast cooked by his wife Amanda. We sit in their kitchen sipping prosecco with the antipasti and get to be part of the family. The cheese course group arrived 45 minutes late at Daniela’s dairy. She had already added the rennet, the enzyme that speeds up coagulation of the curd, to have the curd ready for our planned arrival time. Now it was past its best. We feared we’d ruined her day’s production of cheese. Daniela’s youthful appearance belies years of experience making cheese. She knew the curd couldn’t be used to make a hard cheese to be matured for several months, so we used it to make some soft cheeses: stracchino and raviggiolo. I first went to visit Daniela Pagliai at her organic farm I Taufi early last June. I had learned about it from the address on the wrapping of some exceptional butter I’d come across at a gastronomia in Ponte a Moriano near Lucca. The wrapping claimed the contents were ricotta, so I assumed Daniela also made cheese, and I warmed to a person who wasn’t uptight about precision labelling. (Not that ricotta is cheese, but you have to make cheese first and then use the whey to make ricotta.) The address of the farm was Melo. I didn’t know Melo, but I’d been to the picture postcard town of Cutigliano from which you ascend the Pistoiese slopes of the Apennines, it seems like forever, to get to Melo. What appears on the map to be at the edge of civilisation, turned out to be a hub of pastoral activities with Daniela at the centre. On this first meeting she appeared self-possessed, only mildly curious about my tours and calmly accepting of my request to bring clients to watch her make cheese, as if life often brought novelties to her door. A warm honesty flowed from her candid smile and guileless eyes. She showed me her modern dairy, the maturing room and the cows in the barn. Her younger daughter clung to her apron; the older one arrived home from school. I was much more curious about her than she about me. In the dairy she had fondled a spino, the wooden stick traditionally used to cut curds, so I knew she respected tradition. I asked diffidently whether the cows ever went outside, and was relieved to hear they still practise transhumance, taking the cows to alpine pastures a couple of hours’ walk above where we were now. The cows have to wait until school is out and the whole family can up stakes and move to their summer home. We went to see it without them. On a shelf I noticed a slim book entitled Come le Stagioni: Daniela Pagliai (Like the Seasons), a biography of her written by a friend from Pistoia in the form of an interview. I bought a copy and learned she was practically born making cheese. During school holidays she and her dog herded her father’s sheep. By the time she was 14 she was in charge of the pigs and all the phases of cheesemaking on the family farm. At 16 she married Valter and discovered that his contribution to the marital economy was a herd of milk cows. She moved to her in-law’s farm and transferred her cheesemaking skills to cow’s milk. After five years she and Valter realised their dream of buying their own farm and becoming organic. In the book she sums up her philosophy of life: ‘I think there are many types of “love” all led by the heart. Without its beating, there can be no beginning. I’m not talking only of the beating that pumps blood through our veins, but also the beating for our children, our parents, our house, our land, our work, which are all united in one thing: love. ‘How can I explain to you how much I love my life and my work? How can I make you understand what I feel for my children and my husband? For nothing else in the world and no other life in the world would I change my own life and these loves. ‘For me life is like the seasons: moments of joy are like the flowers and perfumes of spring and like the ripening of its fruit and the embrace of the hot summer sun. Moments of melancholy are like the autumn with its rain, which sometimes also streams from my eyes, and like the winter, because you have to move with the rhythm of the snow, delicately placing your feet like the large snowflakes descending joyously from the sky, sprinkling the roof and our valley, and walking, walking lightly, toward a new spring.’ There was still snow on the ground when I took Giancarlo Russo to visit Daniela in preparation for our new cheese course. He approved, and Daniela became part of the course in which Giancarlo teaches the theoretical sessions. For more information about the Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese course: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/

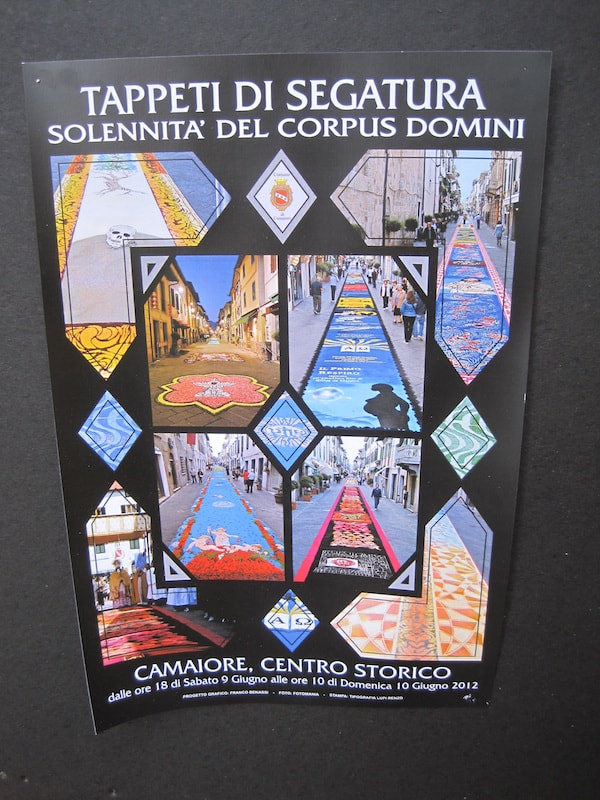

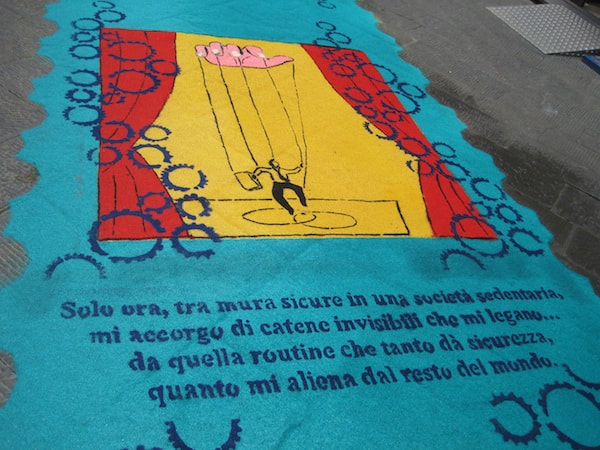

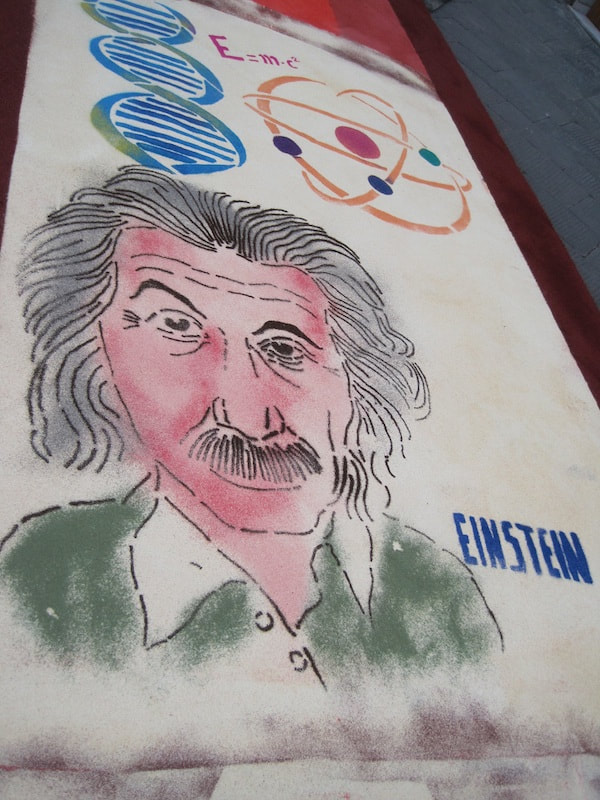

My thanks to Kirby Piazza for his photographs of Daniela and the farm. This sounds like a question you type into Google, but it’s what my clients ask me when I’ve taken them to a cheese maker on a mountain top or a handloom weaver in an unmarked house in a higgledy-piggledy mediaeval hamlet or a village festival that’s only announced by the huge number of cars parked along the road when you arrive. I don’t ask Google. In fact, Google usually hasn’t even heard of the people you visit on my tours. The answer is easy, but long. First, I live here (Google doesn’t). Second, I’m blessed with the ‘satiable curtiosity’ of Kipling’s elephant child. Third, I’m not afraid of appearing ignorant or stupid; the only way to learn is to ask lots of questions. Fourth, I go out and research everything that sounds exciting to me. Here’s an example. During the last 24 hours I’ve been to the festival of Tappeti di Segatura Colorata at Camaiore, the Antro del Corchia, Ristorante Vallechiara at Levigliani di Stazzema, Miniere dell’Argento Vivo, tiro della forma sports club and Ristorante Pizzeria Al Barchetto at Turritecava, Gelateria Gely at Fornaci di Barga. It went like this. Saturday 9 June 7.30–8.30 pm: Drive to Gabriella’s house in Capezzano Pianore, near Viareggio and Camaiore. Gabriella is one of my cooking teachers and has invited me to stay the night so she can introduce me to the treasures of Camaiore. 8.45 pm: Dinner with Gabriella, her husband Alfredo, her son and daughter-in-law. 10.00–10.15 pm: Alfredo drives Gabriella and me to Camaiore to watch the teams of carpet (tappeti) designers. Every year on the eve of Corpus Domini (a Catholic religious holiday celebrated on the ninth Sunday after Easter), patterned carpets of dyed sawdust (segatura colorata) are created on the paving stones of the two main streets of Camaiore. The enthusiastic artists work throughout the night so the public can view the finished carpets before 9.30 am when a religious procession walks along the streets and messes them all up. 10.15–11.00 pm: We join the throngs watching the carpet makers of all ages kneeling on the street to sprinkle sawdust in the correct places to build up complex pictures. 11.00–11.15 pm: Drive back to Gabriella’s house. 11:15 pm: To bed. Sunday 10 June 6.45 am: Rise and shine. 7.00–7.15 am: Quick cup of tea (one English habit I haven’t forsaken) and a dry rusk with Gabriella’s homemade wild blueberry jam. 7.15–7.30 am: Gabriella and I drive to Camaiore. Sensible Alfredo is still asleep. 7.30–8.15 am: Wow! 8.15 am: Church bells ring calling the faithful to mass. Uh oh. That means the procession after the mass won’t start until 9.30 or 10. I have too much research to fit in today to stay, and besides that, who wants to see this beautiful handiwork trodden on? We change plans and head to Pasticceria da Rosanno, Gabriella’s favourite, via a few exquisite little churches she tells me all about. 8.25–8.45 am: Coffee and the lightest Italian brioche I’ve ever eaten. 8.45–9.00 am: Start back to car but I’m sidetracked by Gabriella’s casual comment, ‘That’s a good gastronomia’, as we pass Salumeria Nicola. In we go. It’s difficult not to buy some of everything, but I only get a piece of special pecorino called ‘Scoppolato di Pedona’, which I’ll enter in the England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament during my Cheese, Bread & Honey tour the week after this. 9.00–9.15 am: Return to Gabriella’s house and I hastily depart. 9.15–10.00 am: Drive to Antro del Corchia, a cave I’m vetting for a family for whom I’ve designed a tour in July. In my haste to make the 10.00 shuttle bus, I drive right past the turning to Levigliani and have to go back. That’s one reason why I do these reccies. No time to buy a ticket, but I’m waved onto the bus anyway. 10.15–12.15 am: I’m no cave expert but the woman next to me is, and she’s impressed by the three underground lakes, a column that looks like a Golden Eagle plus a ‘petrified forest’ and ‘organ pipes’, and I’m relieved to hear that extensive tests have proved our breathing is but a drop in the ocean in such an enormous cave, the largest in Italy. No photos allowed in the cave. 12.15 pm: I was intending to go straight to the Miniere dell’Argento (silver mines), but naturally they’re closed for lunch. There’s nothing to do but take the guide’s advice and have lunch myself at the Ristorante Vallechiara at the other end of Levigliani. I phone Katherine, my communications manager, and tell her I’ll be late for the tiro della forma (cheese throwing) in the afternoon. 12.30–1.45 pm: I arrive at Vallechiara without a reservation. No worries. Mamma welcomes me into a pleasantly buzzing dining room where her son lays a table for me right in front of the speakers and mixing deck. I ask whether they can be turned down. No, but he lifts up my table and sets it behind the speakers, where the sound is muffled. A plate of pasta fritta (irresistible deep-fried bread dough), wine and tap water appear instantly (many restaurants make a fuss when I ask for tap water and my friends shrivel with embarrassment). The son joins mamma and a waitress carrying around huge trays of antipasto. Bruschetta, four crostini, salumi and melon, olives and a few other delicacies land on my plate before I can order. It turns out Sunday lunch is a fixed menu. No choice, but who can complain about what’s delivered? 1.45–2.15 pm: I have to be at the mine by 2.00, so no time (or room) for the second main course or dessert. I go to the bar for coffee and to pay. After 10 minutes the son arrives and tells me with a grin it’s much harder to pay than to eat in this restaurant. He sends a woman from the kitchen to make my coffee, but she doesn’t accept money. Finally another man arrives and I’m allowed to pay €20 for my delicious lunch that could have fed three. Incredible! 2.15–3.00 pm: Drive to the Miniere. The next tour starts at 3.00, so I sit in the sun. Someone greets me as a group emerges from the mine. It’s Nicolas Bertoux, a sculptor. I haven’t seen him and his sculptor wife Cynthia Sah in a few years. They’ve got more commissions than they can handle, and they’ve restored the studio and have a permanent collection in their private museum. I must come and bring my guests. I will. 3.00–3.30 pm: We don our hard hats and enter the mine. It’s not a silver mine after all. It’s a mercury mine, one of the rare ones where free mercury sits around on rock ledges in little globules. It’s fascinating, but I’m so late for the cheese throwing that I tear myself away before the end of the tour vowing to return. 3.30–4.09 pm: Up over Cipollaio Pass (no one can tell me why it’s named for an onion field or seller), past the disused marble quarry I take my clients to, down past Isola Santa with its houses with stone roofs. I love driving on the curvy mountain roads. Maybe I’ll become a rally driver as my next career. Through Castelnuovo and down the Serchio valley to Turritecava, left at the sign to Pizzeria Il Barchetto (little boat) and down to meet Katherine and her husband Andrea — I suspect I’ll need a man at the cheese-throwing sports club. 4.09–5.30 pm: Tiro della forma, which means ‘cheese throwing’, is a traditional sport of the Garfagnana. In Cheshire, England, there’s an annual cheese rolling competition, but it’s a tame game compared to this pecorino-hurling sport that goes on throughout the year. I’m here to have a look and talk to the owner of the club about bringing guests, especially during the ‘Cheese, Bread & Honey’ tour. We’ll be making our own pecorino, so why not toss it around too? I watch the pros and suspect a cricket bowler would be envious of their technique. See it in slow motion on our Facebook page. Matteo, the owner, is all in favour of Sapori e Saperi guests. Especially if we dine at his pizzeria. On the edge of his fishing lake, we find the cheerful staff clearing up after a wedding party; we check out the wood-fired pizza oven and approve the excellent menu of other typical local dishes. For half a second I contemplate sticking around until 7.00 for pizza, but add it to my future research list and opt instead for an artisan gelato in Fornaci di Barga. 5.30–5.45 pm: Drive to Fornaci di Barga. 5.45–6.15 pm: Behind the counter of Gelateria Gely is a tall, dark, handsome stranger, the owner Paolo Citti. I’ve heard from Debra Kolkka (Bagni di Lucca and Beyond blogger) that he takes his gelato seriously, and I want my clients to benefit from his long experience. I had already tasted his gelato the week before and compared it to three other gelaterias in the area: it’s in a class of its own. At first he’s wary. Maybe I’m a competitor, his recipes are secret, his laboratory is tiny, he’s very busy in the mornings making gelato for his two shops. I tell him about the other artisans I take my guests to and about how important I believe it is for people to learn directly from artisans how much better their food tastes and why. I win him over in the end. We’ll have a go. I can bring up to three people (I bet he wouldn’t turn four away) for a lesson in the afternoon. Who’s going to volunteer? (The news shop across the road is selling parmesan damaged in the earthquakes. Everyone is pitching in to help the producers.)

6.15–6.45 pm: Drive home weary but exhilarated by the results of my research. Everyone I met was kind and welcoming. They were all enthusiastic about helping me and my clients discover the best of Italy. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed