|

Sant’Antioco is a small island off the southwest coast of the large island of Sardinia, an island squared you might say. Sant’Antioco is afflicted by two winds: the maestrale from the northwest and the levante from the east. One or the other blows nearly every day, but since they take turns, there’s always a calm sea for fishermen on the leeward side of the island.

On a bright spring morning the fishing boats are tied up to the quay, squeezed in side by side. Too many fishermen chasing too few fish.

Many of them augment their income by offering pescaturismo, fishing excursions for tourists. I’m excited. For years I’ve wanted to learn about fishing in the Mediterranean, but it took a long time to find the right place and fisherman.

We arrive at our boat the ‘Alessandro P.’ and the live Alessandro, son of fisherman Mauro Pintus with whom we’re going fishing. Soon Mauro, his wife Roberta and their 14-year-old daughter arrive all lugging groceries. We climb aboard from the stern onto the working deck.

We proceed along a narrow corridor past the engine room and the galley and climb out onto the prow and onto the upper deck where lounge chairs await the non-fishermen in the group.

With Mauro at the helm we chug out into the lagoon to find the nets Mauro and Alessandro set last night. This must be travel at its slowest, apart from crawling. The distance we covered by mini-van in five minutes takes at least thirty in the boat. I thought it might be boring, but at this speed there’s an infinite variety of detail to observe: birds overhead, features on the shore and especially the changing colour of the sea.

After a while we stop seemingly at a random spot in the sea, and the action begins on the working deck. We’ve reached one end of Mauro’s net which he laid the night before. He marks the end by tying an empty plastic container to it which floats on the surface of the sea. Now we learn what the strange wheel on the port side of the boat is for.

The net isn’t anything like I’d imagined. I guess I’d been thinking about illustrations in children’s books of a large square net that gets filled with fish and you pull it up from the four corners. Instead this is a very long, narrow net, about a metre in width and a kilometre long with a thick rope running along each side.

At first there aren’t any fish. Then a couple of sea cucumbers. Not edible, says Mauro. He uses them as bait.

I feel sorry for this creature, but I’m also a carnivore and am sure our ecosystem wouldn’t work if we all lived as herbivores at the bottom of the food chain with no one at the top eating meat. But I also want to be aware of what is being killed and how.

Mauro invites us to help take the fish from the net as he continues to reel it in.

Even though we follow Mauro’s instructions to extract the fish head first, it’s not easy. If lunch relied on us, we might starve.

Finally we come to the end of the net which is piled in a heap on the working deck. Mauro joins us at the task of untangling fish from the net. We soon tire and go look at the scenery from the upper deck.

Good smells waft up from the galley.

When we’re called to lunch, we find the working deck transformed into a cheerful dining room.

I ask Mauro about tuna. We all believe that tuna is fished out. I’ve been avoiding eating tuna for several years, but will have to be polite. Mauro states that there are too many tuna. That’s why the catch is so small. Tuna are at the top of the food chain, and if there are too many, like the wolves eating my shepherd friends’ lambs, they decimate the populations of smaller fish. So why are we always hearing that there are no tuna left? He says it’s mainly due to the politics of fishing. Who’s allowed to fish where and how much. He presents it as a war between fishermen and politicians with marine scientists and environmentalists somewhere in between. Clearly some more research is in order.

He and Roberta and two other fisher families have formed a cooperative to bottle tuna and two fish salads, octopus and mixed seafood. The men fish and the wives work in the bottling plant which we visit when we’re back in Sant’Antioco.

Whatever the truth about tuna, this is the best tuna salad I’ve ever eaten

The zuppetta is a rich tomatoey fish broth ladled over toasted bread.

By now we were struggling, but the fried fish is light and not at all greasy. A joy to eat. But this isn’t the end after all.

Mauro disappears for a moment and returns with his guitar. We hadn’t been expecting entertainment. It turns out Neil Young is one of his favourites, and he’s delighted that Claudia knows a few songs.

We won’t win the Eurovision Song Contest, but it’s a lot of fun.

If you'd like to go fishing with Mauro and indulge in Roberta's stunning lunch, there are still a couple of places left on our Celebrating Sardinia tour from 21 to 30 April 2023.

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here.

If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 21 May 2017.

0 Comments

Very few people I know have been to Sardinia. If they have, they went with the kids and stayed on the beach. If I ask people where in Italy they would like to go, Sardinia is rarely in their top 10. Yet it has so much to offer: Even I only went to Sardinia by accident. Some weavers who were coming on one of my Tastes & Textiles tours in Tuscany asked me to take them to visit a woman who weaves ‘sea silk’, the filaments of the beard of a sea mollusc. Reluctantly I agreed and hopped over from Pisa, only 50 minutes by plane to Cagliari, the capital of Sardinia. It wasn’t love at first sight. But, like people, I believe places merit more than a casual glance. Many reveal their treasures only to those who patiently dig below the surface. There’s no better way to get to know a place than to learn from the locals. Enter Antonio Arca. He was born in Alghero in northwestern Sardinia and moved to London in 2004, the same year I came to Lucca. His company Capo Caccia Fine Food imports the products he knows and loves from small, trustworthy suppliers. During one of my research trips to Sardinia, Antonio advised me to go to Sa Sartiglia festival in Oristano, in the west central part of the island. You can read about it here. I was travelling with friends who wanted to go to Cabras to see the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, but I was too engrossed in the festival. I was meeting farmers and family food producers at street stalls. One of these was Marcello Stara, a local rice farmer. I don’t know why I’m so excited by rice. Maybe it’s the flavour of good rice (not the bland quick-cook stuff) and its versatility in different cuisines from Asia to Italy. Maybe it’s the fact that it grows in water and required communal cooperation to provide the irrigation. Maybe it’s just how beautiful it looks in the field. In any case, I was already conjuring a tour to include Marcello and his rice during the harvest so we could find out how it’s processed and what freshly harvested rice tastes like. But one farmer doesn’t make a tour. I consulted Antonio. Did he know know other people in the area? Would he like to collaborate on a tour? Yes and yes. We planned a research trip together. First we needed a place to stay. For me it had to be an agriturismo (farm accommodation) so we would be investing in the rural economy. I found three suitable ones on the internet. Antonio chose L’Orto. Not only do they have enough private rooms with en suite baths, but they have a restaurant and dad is a fantastic cook. Everything local and perfectly cooked. We visited Marcello and his rice fields. He introduced us to Davide Orro and his family in the next village. Davide could almost be a tour in himself. He’s an enthusiastic winemaker and olive farmer and his sister Ester makes decorated festival bread. He planned our day: start picking olives, cure and bottle the olives, learn to make decorate bread with Ester. Lunch: bread, local cheeses and salumi, olives, wine. One of the grape varieties is known to have been grown in the area 3000 years ago. Davide suggested we go see Sandro Dessé. He’s even more versatile than the Orro family. You arrive at his farm and see a paddock of sheep and goats, one of donkeys and horses, pigs at the back and dinosaurs over to the side. Behind the pigs are fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Sandro is a practitioner of the circular economy. Not only does he produce the raw ingredients, but he processes them as well. There’s a small abattoir, a laboratory for curing pork, a cheese dairy and a kitchen for drying fruit and making pasta. His dining room seats 250 guests. Sandro’s wild, wide-eyed enthusiasm is contagious, but we can’t do everything in one visit. We must have a tour of the farm, and it would be fun to have a lesson making the delicious stuffed pasta called culurgiones, which we can eat for lunch along with Sandro’s many other products. Here we pick up the trail of some of Antonio’s friends. Paolo Lilliu, a butcher, who makes the salsiccia sarda, which you can cook when they’re fresh or air dry and eat like salami. On your morning with Paolo you’ll make your own, after which we’ll go to his friend Sandro Picchedda, a saffron and peperoncino (chili pepper) farmer for a barbecue and a traditional dessert made with saffron. Some other friends of Antonio introduced us to cowherd and cheesemaker Giuseppe Sanna who makes the Slow Food Presidium cheese casizolu from the milk of his own cows. He's willing to let you try your hand at forming the cheeses. My friends came back wide-eyed and enthusiastic about the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, bigger than life-size stone statues of warriors which probably date to around 800 BC. Having been an archaeologist, I had to see them too. Luckily they reside in the seaside town of Cabras, which is also a centre of bottarga production. We talked to several producers who told us about the technique for fishing the grey mullet, cleaning them and salting and curing the roe to make the much sought after and expensive delicacy bottarga. The gentle and generous Giovanni Spanu invited us into his production facility. The Giganti were even more impressive than I had imagined. They immediately became the mascots of the tour—little-known giants, the heroes of their land. Our living giants are smaller and gentler, but fighting all the same to maintain their products of quality and the role of the small farmer and producer in an ever more global economy.

Find out more about the Giants of Sardinia tour here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 26 August, 2018. What does Tuscan heritage mean to you? Do you think of Florence and its famous art and architecture? The leaning tower of Pisa? Maybe the landscape of vineyards, olive groves and pencil cypresses that give us Chianti and olive oil? My Italian friends from Lucca helped me design a tour based on their idea of their own heritage. They envisaged a tour that snaked diagonally across the region from Sansepolcro and Arezzo in the southeast to Lucca in the northwest. Chianti yes, but not the vineyards that leap to mind. Art and architecture yes. But no Florence. No Siena. No Pisa. Here are ten experiences they don’t want slow travellers to miss. 1: Sansepolcro (Arezzo Province) Why there? For two reasons. 1 The fresco of the ‘Resurrection’ by the hugely influential early Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca. You don’t have to be religious to be spellbound by it. Aldous Huxley called it the ‘greatest picture in the world’. 2 The Tuscan cigar. I don’t smoke and I think it would be better if no one did. But it turns out that tobacco was undoubtedly a major player in the history of Tuscany ever since 1574 when it arrived in the very spot we’re staying: Sansepolcro. From smuggling to women’s work you’ll hear all the pros and cons of tobacco at Roberta’s tobacco farm. Whatever your views, it’s fascinating seeing how tobacco leaves are harvested by hand and smoke-dried. 2: Anghiari (Arezzo Province) An English friend who accompanied me on a research trip said that of everywhere we went, it’s the place she most wants to return to. Its striking position poised on a cliff edge is attraction enough. Add to that a tour of the Jacquard looms at the Busatti linen mill, and you’ll want to return too. 3: Chianti (Florence Province) Could Chianti wine be even better if they restored all the dry-stone walling that was demolished when tractors blazed a trail through the vineyards in the 1960s and ‘70s? You can judge for yourself during a vineyard tour and tasting. 4: White Truffle (Pisa Province) San Miniato claims their white truffles are better than the more famous ones from Alba in the Piedmont. Follow the Lagotto dog, find your truffles and relish lunch with truffles in every course (except dessert). 5: Vicopisano (Pisa Province) When the Florentine Republic conquered the Pisans in 1406 they commissioned their star architect-engineer, Filippo Brunelleschi—famed for the dome of the duomo of Florence—to redesign the Pisan fortress at Vicopisano. My historian friend from Pisa says you mustn’t miss this magnificent castle, and he’s going to show you around himself. 6: Extra virgin olive oil My Slow Food friends are sure you have no idea how good extra virgin olive oil can be until you taste it here in Tuscany. It deserves the same attention you lavish on wine. 7: Lucca (Lucca Province) Lucca is so conservative that it never tore down its Renaissance walls, as if waiting for another attack. It may as well be us. And who better to show us around than a descendant of one of the noble families who ruled Lucca in the Renaissance! 8: Puccini (Lucca Province) Baritone Mattia Campetti insists that every visitor to Lucca must hear the music of that great operatic composer Giacomo Puccini in his home town. Mattia will give you a vivid and amusing tour of Puccini’s home at Torre del Lago. Be prepared for an entertaining concert when Mattia is joined by his soprano wife Michelle Buscemi. 9: Tuscan grill On the grill are a pig and a cow (no apologies for sneaking in two items here): the indigenous Cinta Senese pig (belted pig of Siena) and the white Chianina cow, possibly a descendant of the huge Palaeolithic aurochs. Their succulent flavour hasn’t diminished at all over the millennia. 10: Cantuccio (biscotti in English) Every Tuscan meal must end sweetly with cantuccini dunked in vin santo, our Tuscan dessert wine. How to book the Tuscan's Tuscany:

If my Tuscan friends have convinced you to come see Tuscany through their eyes, have a look at all the tour details here (click on the tabs below the introduction and read what appears in the window below) and email me for a booking form. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. If you come to Lucca for only a day, arriving from Florence late morning and off early the next to get to the Cinque Terre, you’ll miss the pleasures of Borgo Giannotti. Compared to the amphitheatre, the Guinigi Tower with oaks growing on top, the wedding-cake columns of San Michele church and the massive encircling walls of the historic centre, Borgo Giannotti doesn’t look like much. Immediately outside the north gate of Lucca, it was a meeting point for merchants coming from the port of Viareggio, a place to stop and refresh themselves before turning up the Serchio Valley to sell their merchandise in the Garfagnana. It developed into a thriving artisan quarter, and retains that vibrancy of people making and doing things, occupations that the waves of mobile phone shops haven’t yet totally swept away. So come with me for a Saturday morning trawl in Borgo Giannotti. We might be mistaken for drunks, rare as they are here in Lucca, weaving from one side of the street to the other following the trail of my favourite places. On the left we come to coffee importers and roasters Bei & Nannini. It’s not my favourite coffee, but I like the shop front and, apart from the coffee beans themselves, it’s local. It was founded in 1923 by Guido Nannini and Giovanni Bei and is still in the ownership of the two families. There are many small groceries, delicatessens and specialist food shops in Borgo Giannotti. You can do all your shopping from the friendly vendors in the space of a few hundred metres without ever entering the anonymity of a supermarket. Crossing over to the right we find a fishmonger. Over on the left is one of many fruit and vegetable shops. Since it’s Saturday, we’ll continue up the street to the farmers’ market. Still on the left, look at that exquisite tiled shop front (it was even more beautiful before some developer painted over the ochre wash above). On the right we come to a bakery with many enticing goodies in its window. I suspect torta di erbi is a relict of Renaissance, and maybe mediaeval, times when sweet and savoury were often mixed in a single dish. As strange as it sounds, this delicious tart is filled with Swiss chard, parsley, bread crumbs, raisins, candied peel, pine nuts, grated pecorino and parmigiano, sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, rum and eggs. Becchi means ‘birds’ beaks’ and refers to the form of the pastry; shaping them is a skill in itself. Over on the left again is a tap where locals come to fill their water bottles for drinking at home. It’s free! Next to the fountain is Angolo Bazaar where you can find almost any utensil or container you need for your household and many gifts to take to friends at home. It used to be on the corner (angolo), but moved down one space to make way for a discount sport shoe shop. Via Stalle means street of the barns—something like a mews in London. You could spend a couple of hours in this Aladdin’s cave starting with the baskets at the front and penetrating into deeper and deeper caverns stacked from floor to warehouse ceiling with crockery, wooden kitchen utensils, garden tools, hosepipes, canvas—an inventory too long to list. I’ve brought my sickle and pennato lucchese (a kind of billhook) to be sharpened opposite at L’Arrotino. Many people take their utensils to artisan sharpeners, and itinerant ones come to some open-air markets. The Bertinis have been sharpening knives in Borgo Giannotti since 1956. They also sell quality knives from those forged traditionally in Italy to Japanese knives of Damascus steel. Every kitchen needs at least one! Continuing on the right, we come to a delicious smelling grocery stuffed with tasty products, including tortellini fresh from the Favilla pastificio of Lucca. There’s something special along the road to the right, but first we’ll continue to the top of Borgo Giannotti. When it’s lunch time, we can eat at Buatino, where the cook changes the menu every day to take advantage of seasonal ingredients. We cross over the outer ring road and come to the Foro Boario. This has nothing to do with wild boar. Boario refers to cattle and the Foro Boario was the cattle market, used in September when herders brought their animals to sell in the city. The Festa della Carne e della Macelleria Tradizionale (Festival of Meat and Traditional Butcher Shops) held annually in the middle of September commemorates this practice. More in the old spirit of farmers selling their produce to the public is the farmers’ market that takes place at the Foro every Saturday morning. If you buy your fruit and vegetables here, they’ll be fresh and seasonal. You’ll meet the growers and can ask for recipes for ingredients you’ve never used before. Time for a coffee at the bar opposite the Foro and then we walk back to the monument, which turns out to be a road sign. We turn left and if I weren’t with you, you’d walk right past this grey-green building and boring gate. You would be missing a great treat. It’s a handmade tile factory founded by the current owner’s great-grandfather in 1902 to make tiles in the ‘Liberty’ or Art Nouveau style, which was all the rage in Europe at the time. Press your nose against the dirty showroom window (perhaps never washed since 1902?) and you can see some of the patterns that Francesco Tessieri’s four artisans still make by the same techniques. They’re closed on Saturdays, but if we come on a weekday, Francesco will take us into the workshop and explain as we watch the process. Among his many commissions were restorations of floors in the homes of Gucci and Pavarotti. Around the corner are some over-the-top examples of ‘stile Liberty’ houses whose floors are surely paved with Tessieri tiles. Our tour is done and it’s time for a delicious lengthy lunch accompanied by good wine and conversation. So like the merchants of old, why don’t you make Lucca your city to dawdle in, to catch your breath and refresh yourself?

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 13 January, 2013. If you’ve been to the mountains of Italy, I bet you’ve asked this question yourself. You’re probably in a car on a road hugging a river and you’re craning your neck to look up at a terracotta-roofed village improbably balanced on an inaccessible ridge. To find the answer you have to abandon your car, get into your time-machine, key in ‘Middle Ages’ and click GO. With no discomfort on the way, you find yourself on a broad cobbled road nearly at the crest of the ridge looking down at that very spot in the valley you just vacated. You see the river running swiftly in the shadow of sheer rock walls that not even a mountain goat could scamper across. Your car is nowhere to be seen, because the road won’t be cut through the rock for several centuries. Your eyes follow the river to the left where it emerges from the gorge, still in the shade at noon, and disappears into a thicket of dense scrub on a river plain that floods in winter. You walk next to your mule laden with your jeans, T-shirts and iPad and in five minutes emerge into full sunshine at the ospedale next to the church in the village, where you are welcomed by a monk and offered a meal. As you tuck into your succulent boiled salt pork ribs, a large bowl of tasty chestnut-flour polenta and a skin of wine, you’re cooled by a soft mountain breeze that ripples through the golden farro in small terraced fields. A couple of enormous black pigs with pink belts around their middles wallow in a puddle formed by the spring that issues from higher up the mountain and provides clean cold drinking and washing water for the village. It must have been hard work creating the terraces, but the place is swarming with strapping young sons who look as if they’ve been down the gym pumping iron all morning, and it’s obvious time isn’t in short supply either. After lunch you’re not allowed to depart before having a snooze on a bed of hay in the inn, air-conditioned by the thick stone walls. Although you’ve signed up for a slow travel tour, you still have to get to the next village by evening. A shepherd setting out with his flock offers to accompany you and show you the way, not that you need help to follow the broad, well-maintained mule track bordered by dry-stone walls. He’s been visiting his sister who married one of the men in this village, and his aunt and uncle live here too. There are many family connections between adjacent villages on this slope and those just over the top behind the village. It’s all so convenient living right on the main mule track; nothing is much more than an hour’s walk away. As you amble along, he tells you that the village you’re heading for lies just below a fort, part of the Republic of Lucca’s line of defense against the warmongering Florentine Republic. The ridge serves as an ideal lookout point, but the garrisoned troops are always drunk, and he’s sure those sheep that went missing provided Sunday lunch for the officers. Besides, he lowers his voice conspiratorially, he and a couple of other shepherds, who know the tops of the mountains like the eagles, had a good trade in contraband chestnut flour and firewood with the Florentine citizens just over the border. All at an end now, of course. After about 50 minutes, at a fork in the road, the shepherd bids you farewell as he continues up to his house in the summer pasture half an hour away and you saunter down the slope to the village bar just in time for a gin and tonic and a pizza margherita. Oops! You must have accidentally hit the ESC key on the time machine. You can tell because they didn’t have tomatoes in mediaeval times, and there are those telltale electric fairy-lights in the bar garden. Oh well, now that you’re back, let’s do the return trip as a 21st-century hiker. The mule track, being inaccessible even by a Fiat Panda 4×4, has become overgrown, many of the cobbles have washed out and in places no trace is left. No matter. You shoulder your rucksack and set off down the tarmac road to the valley bottom, which takes 45 minutes. Turn left and walk along the state highway cut into the sides of the valley or raised above the boggy valley bottom. The sun finally got here at about 12.30 pm, the tarmac is still blazing hot and there’s no cooling mountain breeze down here. An hour later you arrive at a village in the valley bottom, built mostly since the 1950s to be near the factories that exploit the river water. Turn left and for another hour and a quarter climb steadily following the interminable switchbacks of the car road, built in the late ‘50s, to arrive after a grand total of 3 hours back where you had lunch. QED. Where did that mule go? If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here.

If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 7 March, 2011. As a tour designer and guide I don’t get many opportunities to experience what it’s like for you to travel to a place you’ve never been to before. The only chance I have is when I research a new tour or course. And I did just that in March 2018. I want to offer a mozzarella course (update: I now do). Since we don’t make mozzarella in Tuscany (not properly, anyway), I had to go to Campania in the south, the home of water buffalo and birthplace of mozzarella. You probably know Naples, Pompei and the Amalfi Coast, but I hadn’t even been to any of these. It was a bit daunting going south of Rome to the infamous Mezzogiorno of lawlessness. But I had a big advantage over the average tourist: I had locals to show me around. I had met a Scottish woman on a Ryanair flight from London Stansted to Pisa. Her Italian husband was from the province of Salerno, just south of Naples. I knew that Salerno and Caserta provinces were famous for their mozzarella. When I told her of my plan, she said they live in Florence now, but her husband knew the Cilento area inside out (central and southern part of Salerno Province). A couple of months later I found myself at Santa Maria Novella station in Florence, boarding a train bound for Salerno with Audrey and Enrico. I was to stay at their house in Trentinara. They were renting a car and they were going to introduce me to owners of agriturismi (farm accommodation), a mozzarella dairy and restaurants. Everything I would need for the course. First a stop at an agriturismo Aia Resort Cilento owned by Vincenzo, an architect friend of Enrico’s. It’s perfect for the course: tasteful rooms with private baths, a swimming pool, pizza oven and BBQ. It was after dark when we arrived at their house and, while Enrico lit the fire, Audrey took me next door to meet her mother-in-law Antonietta. Even though we planned for dinner to try the restaurant owned by Enrico’s cousin, it was compulsory to sit down at the table to sample Antonietta’s stuffed artichokes (carcioffule ‘mbuttunate), lately picked from her garden. I had to forcibly prevent her putting two on my plate. The next morning we met my cheese and salumi courses colleague Giancarlo Russo, who had arrived separately, and proceeded a short distance down the road to a private house to meet Lilla and her son Antonio La Mura. Lilla is a great cook (as it seems is everyone from this area) and might give a short cooking lesson either during the mozzarella course or during an optional extension before the course. We gathered around the table in the kitchen to talk. But no talk without food in these parts. Antonio went to the cellar and came back with his own salsiccia (air-dried sausage). Lilla sliced her homemade bread, made with sour-dough starter and baked in a wood-fired oven, while Antonio uncorked a bottle of excellent homemade wine. Giancarlo and I have tasted a lot of sausage and salami in our day, and this was exceptional. Encouraged, Antonio disappeared down below again and re-emerged with two cheeses and a salami, all of his own production. Last (at least we were hoping it was), a cured sausage called nnoglia, which was stuffed with lungs and other of the least noble parts of the pig. Usually it’s used to flavour vegetable soups, but Lilla threw it on a grate over the fire that warmed the room. More delicious than you can imagine. She just happened to have some pastries from the local shop, and we weren’t allowed to leave without coffee and a digestivo, her homemade finocchietto, alcohol infused with fennel leaves and flowers. Good thing we hadn’t booked lunch at a restaurant! After that feast of salumi, we had to see Antonio’s pigs… and his cows… in the oak and chestnut woods where they have parties in the summer. That evening at 10.30 Giancarlo and I had an appointment at Caseificio Prime Querce to watch the whole process of making mozzarella and its pasta filata (spun curd) relatives scamorza, burrata and caciocavallo. The head cheesemaker Antonio (everyone seems to be named Antonio) is, of course, a close friend of Enrico. He showed us every step, explaining the reason for each process and giving us generous samples to taste. But the mozzarella wouldn’t be at its peak until it had bathed in brine for another five hours. We finally left around 2.45 am. The next morning Antonio stopped by Enrico’s house to drop off two bags of mozzarella, one hand-formed and the other moulded by machine. It was a revelation! Juicy, firm and milky. How can I go back to eating week-old mozzarella in Tuscany? We still hadn’t had a tour of the town with Enrico and Audrey, so we set off up the streets of Trentinara, hailed and stopped at every corner by Enrico’s cousins and friends. At the top we made the day for Zì Cosimo, the basket weaver. I learned that here ‘zì/zà’, literally meaning ‘uncle/aunt’, is a title of respect for older people. On the way to the restaurant for lunch we passed Enrico’s aunt carrying a basket of freshly baked bread from her wood-fired oven. We were wondering how we could stuff in lunch after gorging on mozzarella for breakfast, but we needn’t have worried. Locanda Lu Vottaro, owned by the chef Cristina—you guessed it, a friend of Enrico, was closed, but she opened specially for us and prepared a superb tasting menu. It was time to leave our friends Audrey and Enrico, this town and the people who we felt we already knew well. Suddenly I realised this must be what it’s like to go on a tour with Sapori e Saperi Adventures. You’re met at the station, transported to your accommodation, escorted to see places and meet people you could never find on your own. They open their arms to you because you’re accompanied by us, their friends. What better way to spend a holiday?

Take a look at the result of this course for professional cheesemakers and keen amateurs: Mozzarella & its Cousins. If you're not a cheesemaker, don't worry, there are less specialised small group tours and courses like Olive Oil: Tree to Table for you. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 28 March 2018. The guests on our inaugural Giants of Sardinia tour excelled themselves with a little help from our stellar food producers. They scampered to the top of the megalithic nuraghe Barumini. They picked and brined olives with Davide Orro and his mother Angelica. They manipulated with dexterity the dough for Oristano wedding bread with Davide’s sister Ester. It was no problem at all tasting the rest of Davide’s superb wines with seductive labels designed by his other sister Maura. They learned the proper way to make Italian risotto with Marcello Stara’s rice under the tutelage of his friend Rossella. With butcher Paolo Lilliu they overcame the difficulties of stuffing Sardinian sausages… …and ate them barbecued for lunch. Even if their Casizolu, a Slow Food caciocavallo-type cheese, wasn’t quite perfect, it was lots of fun modelling the curd. It seemed that making stuffed pasta culurgiones was going to defeat them, but practice makes perfect and success was theirs in the end. I’m glad we didn’t have to do battle with the Bronze Age nuragic giants at Cabras. But I bet our guests would have succeeded in making a peace treaty, and the giants would have joined us for a blow-out feast at our agriturismo L’Orto! Come on one of our small group tours so you too can glow with achievement and join our guests’ hall of fame. Choose your tour now: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/small-group-tours.html

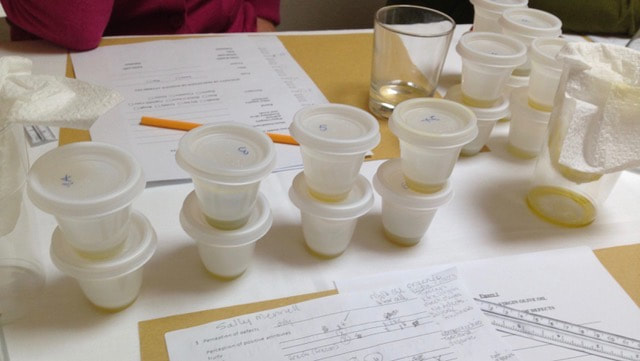

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 11 November 2018. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 28 January 2017. Did you know that olive oil is the only common cooking oil that is the juice of a fruit? All the other oils we use in our kitchen come from seeds: sunflower, rapeseed (canola), peanut and grapeseed. This realisation leads directly to another question. Would you cut an orange, leave it on the counter for a week and then squeeze and drink the juice? Would you step on an apple, leave it on the table for three days and then eat it? Yet that’s what happens to many olives before they’re pressed to extract olive juice. I’ve tasted and written a lot about olive oil, but this idea had completely escaped me until I met Elisabetta Sebastio last year. She’s a professional olive oil taster both for Italian Chambers of Commerce and international olive oil competitions. We ran our first full-day olive oil class during my Autumn in Tuscany tour in November 2016 (now we run a full course on the subject of olive oil: Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany). It was a revelation for all of us. We gathered around her kitchen table. She taught us how the professionals taste and rate oil. We tasted eight olive oils. The first was a surprise and I don’t want to ruin the impact by telling you what it was. Then there were four new-season oils: one from Sicily, two from Tuscany and one from the Abruzzo. Some people liked the tomato scent of the Sicilian one, others the bitter piquancy of the Tuscans. Lots preferred the less in-your-face qualities of the Abruzzese. Under Elisabetta’s guidance it was so easy and we were proudly feeling like experts when we started on the three defective oils. Wow! It was so clear that they didn’t measure up, and we could describe what was wrong with them: rancid, vinegary and fusty. We didn’t want to put them in our mouths. You’ll taste lots of mildly rancid oils in restaurants due to poor storage in clear bottles in the warmth. There were more revelations. Contrary to popular belief, true extra-virgin olive oil has the highest smoke point of any vegetable cooking oil. Another fact some people don’t realise is that it deteriorates with every passing day, even in a sealed bottle. If you’ve got some excellent oil, carpe diem. It will be worse tomorrow. But olive juice isn’t just for cooking. In Italy it’s mainly used as a condiment, like salt and pepper. This got us thinking about which olive oil goes best with which foods. Elisabetta had devised a lunch to demonstrate the classic pairing of regional dishes with an oil of the same region. We got to help prepare orecchiette (an ear-shaped pasta from Puglia) with an artichoke sauce seasoned with extra-virgin olive oil from Puglia. Sadly, we ran out of space in our stomachs before we could taste all the different dishes Elisabetta had prepared. I took another group to her home in December. One of them loved chocolate and Elisabetta assured me she could source some olive-oil flavoured chocolate. The platter of chocolates was beguiling and they tasted fantastic. She had made them herself! Join me on the course Olive Oil: Tree to Table in Tuscany from 18–23 November 2021 and meet the amazing Elisabetta and have fun with olive juice.

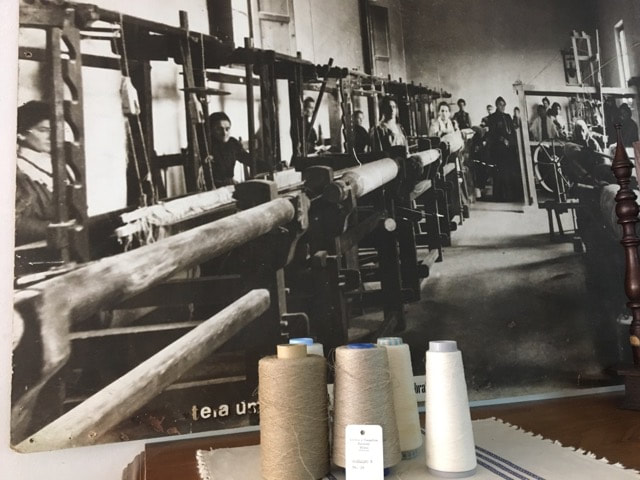

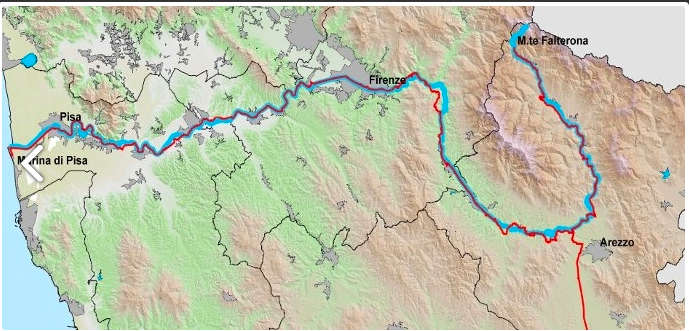

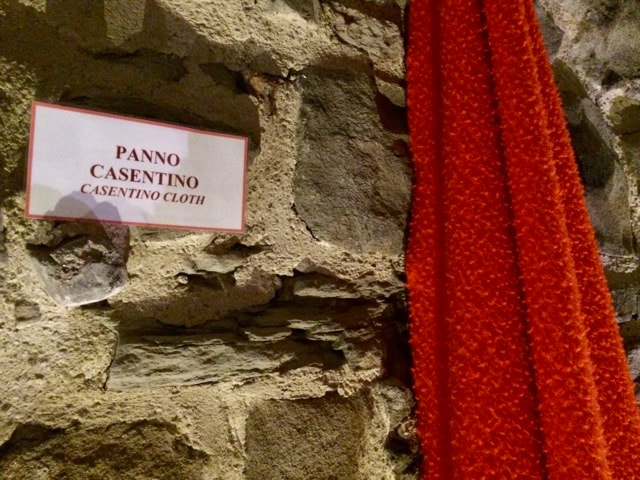

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. Another tour that didn't take place due to the coronavirus. Since many of you enjoyed the virtual Celebrating Sardinia tour and the Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I’m going to lead you on a virtual Woad & Wool tour. Arm yourself with a cup of coffee or a glass of wine and enjoy the journey. Since my tours take you far away from the well-trodden tourist routes, a couple of maps will help you get your bearings. Saturday 16 May 2020 You’ve already arrived at Arezzo, a beautiful little town in southeastern Tuscany. I advise arriving a day or two before the tour so you can get to know it. There are many things to enjoy, and I only take you to the ones you probably won't find on your own. You’re probably a weaver or spinner or dyer, or maybe you’re interested in beautiful handcrafted objects even though you don’t make them yourself. You definitely like eating good natural food made with local ingredients! Right now we’re having lunch at my favourite restaurant in Arezzo, La Tagliatella, where mamma is in the kitchen, a son is a distinguished sangiovese wine sommelier (Chianti is mostly sangiovese grapes) and I’ve never seen another tourist. I introduce you to my dear friend and co-leader Cheryl Alexander of Italian Excursion, and we’re all talking excitedly as we get to know each other. After lunch we drive east and slightly north, over a mountain pass from Tuscany into the region of Le Marche. Take a good look at the trees. They were felled and floated down the Tiber River to be used as beams for many of the magnificent churches of Rome. We descend to the Metauro River valley and arrive at Oasi San Benedetto, a 9th-century former Benedictine abbey. In the abbey dining room, dinner cooked by the inimitable Patrizia Carlo is super-abundant and anything but plain. The first of our stomach-stretching exercises. Sunday 17 May 2020 Today we get to know the Metauro River valley. Fifteen minutes down the valley is Mercatello sul Metauro. Beatrice Cantucci has organised our morning, which starts with a tour of her mediaeval town. As fascinating as her tour is, it’s the women of the local lacemaking club and the men of the Academia del Padlot who win the day. The women are such good and patient teachers that you manage to make a creditable strip of lace even if you’ve never touched a lace bobbin before. Of equal skill among the pots and pans of the kitchen are the men who cook our lunch in their clubroom over a bar (=pub). They’re delighted when I ask if we can come into the kitchen to watch them at work. I’d be incredibly nervous frying so many eggs, but there’s no better combination than perfectly fried egg and the crispy fried goleta di Mercatello (pork cheek similar to bacon). After lunch some of you might opt to go back to the monastery for a virtual rest, but I wouldn’t advise it because our visit to the Roman house in Sant’Angelo in Vado is too interesting to miss. Unfortunately for the inhabitants, but fortunately for us, in the 6th century AD the Ostrogoths totally destroyed the town and it was completely silted over by the Metauro River. The mosaic floors of the Domus del Mito (House of Myth) are so well preserved that you feel as if the Roman family, who lived here toward the end of the 1st century AD, have gone shopping and will be back soon. Monday 18 May 2020 Today is our virtual woad dyeing workshop with Max, one of the highlights of our virtual Woad & Wool tour. We roll out of bed, grab some breakfast and meet Max next door at his Museum of Natural Colours. The lengthy preparation of blue dye from leaves of the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria) made it affordable only by the aristocracy. One of those was Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, who ruled this part of Le Marche in the 15th century. I’m sure you know this portrait by Piero della Francesca, who we’ll meet later in the tour. He’s depicted in red, but in fact the Montefeltro colours were blue (woad) and gold (reseda or dyer’s weld). I hope this year was a better year for reseda. Since last year was terrible, we used imported annatto instead. Max does lots of workshops with children, and besides the dyeing, you find yourself grinding pigments and painting with them. In the afternoon we join Patrizia in the kitchen for a lesson preparing food of various colours. 'I just got some local violet potatoes’, she says excitedly. ‘Let’s make gnocchi’. And you do. Tuesday 19 May 2020 Sad to say, this morning you must leave the virtual Oasi di San Benedetto, but I promise you that the rest of the virtual Woad & Wool tour will be equally entrancing. We drive from the region of Le Marche back over the mountain pass into Umbria. A friend of mine who studies history obsessively explained to me that Le Marche translates as ’The Marches’ which in mediaeval Europe was a border between realms, in this case three: Tuscany, Umbria and Romagna (now part of Emilia-Romagna). We are touring the orchards at the Archeologia Arborea (Arboreal Archaeology) with the inspirational Isabella dalla Ragione. With her father she started salvaging ancient local fruit varieties, many dating back at least to the 15th century. She studies their representations in paintings and books and has discovered recipes for how they were used. There are so many more interesting facets to Isabella’s life that I can’t tell you everything in this small space. A good reason to come on the real tour in May 2021. It’s a 10-minute drive into Città di Castello where we have lunch at Trattoria Lea, take a quick look around the town and meet at Tela Umbra a Mano for a private tour of the linen mill and its museum. Can you believe, they are still weaving fine linen sheet-width fabric by hand! Two women sitting next to each other at each 19th-century loom. In the museum you see antique Perugia towels, the blue decoration dyed with woad. Sorry no photos allowed, so you’ll have to come to see them. And there’s a touching love story and a friendship with Maria Montessori, the founder of Montessori schools. We could easily spend more time in this fascinating city, but it’s getting late and we have a half hour drive to our accommodation at Agriturismo Terra di Michelangelo. Wednesday 20 May 2020 Last night our virtual Woad & Wool tour took us to Agriturismo Terra di Michelangelo. Yes, that most famous Renaissance artist was born only 10 minutes from the farm. I’m not taking you there because on my research trip I decided, although they’ve done their best, a simple house is just a house. Instead we’re going to Anghiari to visit the much more exciting Busatti weaving mill. It’s still in the private ownership of the Busatti family, and the first time I went I was privileged to be shown around by Giovanni Busatti himself, who even took us up to the private guest apartment on top floor. Today Michelangelo Formica, head of sales, leads us into the bowels of the building where the 19th-century jacquard looms are clanking away. Michelangelo shares my philosophy about the value of quality. When he’s at an international textile fair, if he’s approached by a buyer asking for his lowest price, Michelangelo replies, ‘I’m not the right supplier for you’. At the end of the tour, you can’t resist buying some of their luscious linens. It’s worth checking the scrap room where you’ll find real bargains. Until you come on the tour in May 2021, you can shop online at here. If any restauranteurs are reading this, Busatti will work with you to create unique table linens for your restaurant. Sorry if this sounds like an advertorial, but I love the people and the establishment. Depending on how long you spend shopping at Busatti (last year Jenny bought fabric for a huge table cloth), you have free time to explore Anghiari and have lunch. I have two favourites. Last year I went to Talozzi Bistro, so today I’m going to the Cantina del Granduca (the Cellar of the Grand Duke). It sounds posh, but don’t forget it’s his cellar where a mother and son preside. You can even get a good salad, which by now you’re really craving. Soon it’s time to meet in the main piazza for the 10-minute drive to Sansepolcro. The early Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca was born here, and we’re going to the Civic Museum to see some of his work. The masterpiece here is his 'Resurrection'. Aldous Huxley called it the greatest painting in the world. This absorbing video gives you an excellent foundation for our visit. After the museum, some of you visit the Aboca Museum of medicinal herbs and others wander through the town. I’m going to the duomo to revisit a painting that makes me laugh. Now we return to our agriturismo to learn how to make the classic Tuscan cantuccini (you probably call them biscotti), which are so good after dinner dunked in vin santo (Tuscan dessert wine). But first a relaxing aperitivo on the terrace. Gabriele serves us the salumi (prosciutto, salami, etc) he makes from his heritage Cinta Senese pigs. Thursday 21 May 2020 Today the virtual Woad & Wool tour heads north into the Casentino. Never heard of it? You’ll know it well by the end of the tour. It’s only an hour’s drive through rolling hills to the mediaeval fortified town of Poppi where we meet Luca Bellugi at the workshop of his late aunt Elisa. She was an accomplished weaver and fashion designer, but is most famous for having woven a blanket for the Pope and curtains for Jacquie Kennedy. It’s lunch time, and I hope by now you have complete trust in me. If not, your heart will sink as we drive onto the forecourt of an Esso station. We enter the small marquee at the side and there before us, as if by magic, is an elegant dining table. Course after elegant course of local food paired with local wines arrive in the hands of the three Marzi brothers and their nephew Francesco. After our virtual gourmet lunch at the Esso station, we’re happy to reach the Castello di Porciano above Stia where we’ll stay until the end of the virtual tour on Monday. Now we’re dining at the water mill Mulin di Bucchio, very near the source of the Arno River, the one that flows under the Ponte Vecchio at Florence and down to the sea at Pisa. You can see its strange route here from top right (near where we’re sitting) running south and hanging a U to go back north to Florence. I don’t know why, but water mills fascinate me. Perhaps it’s the simplicity of the machinery (even I understand how it functions) and the energetic efficiency. Naturally flour is the protagonist of the meal. Friday 22 May 2020 Everyone who wants a virtual morning walk in the sun down the hill from the castle to Stia should leave now. Those going with the driver can relax for another 15 minutes. We arrive at the Museo dell'Arte della Lana (Museum of the Art of Wool) for our tour and weaving workshop with Angela Giordano. The museum is in a woollen mill, a beautiful example of 19th-century industrial architecture. All the machinery was powered by water. It finally closed in 2000 after a steep decline due to competition from synthetic fabrics. The strong, warm rustic wool is called panno casentino. After being woven the fabric is fulled (washing and beating to compact the fibres) and napped (pulling up fibres using hooked needles to create a fuzzy surface). Both processes increase the water resistance and warmth of the fabric, important characteristics in a shepherd's cloak as well as garments intended for an aristocrat's draughty castle. I first heard about the museum when I received an invitation to a temporary fashion exhibition there. Angela leads us in a weaving workshop. Experienced weavers can do monk’s belt weaving, and the rest backstrap weaving. It’s only a 5-minute walk to our restaurant on the old main street of Stia. On our way we step into Pieve Santa Maria Assunta. When you’re in a romanesque church, always look up. The capitals of the columns often depict strange pagan creatures. Filetto restaurant next door presents a short menu of typical Casentino dishes. I’m having acquacotta. It means ‘cooked water’, but is in fact yet another Tuscan dish for using up stale bread. You stew onion, celery and tomatoes in vegetable broth, and at the end of the cooking poach one egg per person right in the pot. After lunch we finish our workshop with Angela, before going next door to Tessilnova. where owner Claudio Grisolini is expecting us. It was his father who popularised panno casentino culminating in Audrey Hepburn wearing a coat made of it in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’. Claudio takes us behind the scenes to a vaulted room which was part of a woad processing mill. It’s been a full day. Time to relax with an aperitivo and dine at Osteria Toscana Twist—local Tuscan ingredients prepared with a modern twist. Saturday 23 May 2020 Virtual yesterday was dedicated to weaving and textiles. Virtual today it’s food. We’re off to visit cheesemaker Lorenzo Cipriani and his pasta wizard mother Miranda. Picture yourself travelling along winding mountain roads and then a dirt track to their sheep farm at the end in the Casentino Forest National Park. It’s a beautiful day, and Lorenzo decides to make cheese outside. In the photo below he’s taking curd from the pot to make raviggiolo. You probably haven’t heard of it, partly because it’s only made in a few places in Tuscany, but mainly because you have to eat it very fresh, within two or three days. Way too short a shelf life for supermarkets! We have it as antipasto for lunch drizzled with Lorenzo’s olive oil. Next out of the cheese pot is pecorino. Lorenzo cuts the curd to allow the whey to come out, then gathers the curd with his hands, lifts it from the whey and puts it in moulds to drain and eventually to age. In the kitchen we gather around Miranda to watch her make tortelli di patate (potato ravioli), a speciality of the Casentino. We don’t make them in my part of Tuscany. To you they might sound like carbohydrate stuffed with carbohydrate, but they’re wonderfully light and flavoursome served with sage butter and grated pecorino. You have a free afternoon on the virtual Woad & Wool tour. Maybe you walk on one of the many paths around the castle or maybe you write emails to family and friends or maybe you relax in the sun. Now we’re at dinner at La Buca in Soci, just down the river from Stia. Last night was your chance for vegetables. Tonight the speciality is tagliata. Tagliata means sliced. In Tuscany it's a thick rib steak, grilled rare and cut vertically into slices. There are other dishes on the menu, but if you like beef, this is the place to have it. They serve it with the most more-ish fried potatoes I’ve ever eaten. Sunday 24 May 2020 I’m so excited about today’s activities on the virtual Woad & Wool tour. I’m taking you to the Osteria da la Franca at Corezzo for a hands-on lesson making the tortello alla lastra and then to the herbal pharmacy and hermitage of the Benedictine Monastery of Camaldoli. Tortello and raviolo are members of the same family: little stuffed pasta pillows (if they end in ‘i’, they’re plural). What you call them depends on where you are and what they’re stuffed with. The tortello of Corezzo is stuffed with potato, similar to the tortello Miranda made for us, but they’re not cooked in boiling water. Instead they’re cooked on a lastra, a slab or sheet or plate, in this case of stone which is heated over an open fire, like a griddle. Owners Daiana and Mattia (and their three young children) welcome us and introduce us to their cook Loredana. She’s a patient teacher and you’re excellent students. Don’t eat too many! Loredana and Mattia have prepared a big lunch for us. As we drive along the mountain road to Camaldoli, are you thinking, ‘Why another Benedictine monastery? We’ve already stayed in one.’ Camaldoli is different. There is still a community of monks and hermits living here. The setting is extraordinary. Not bare and rocky like the nearby and better known Sanctuary La Verna where St Francis is said to have got the stigmata. Here the mountains are lush and wooded, because for centuries the monks planted 4–5,000 fir trees every year, helping prevent global warming before it became critical. We visit the herbal pharmacy at the monastery. The museum is full of fascinating instruments: stills for distilling essences and huge ceramic storage jars. I would have liked to have walked up to the hermitage, but since it’s raining lightly, we drive. We glimpse the hermits’ simple houses through a gate. But it isn’t all austerity, as testified by the interior of the chapel. We take a different route down and pass a clearing full of Eremurus bulbs glowing like candelabras in the misty air. We arrive slightly chilly and damp at the Locanda dei Baroni, opposite the monastery, happy to find a fire burning in the hearth. Monday 25 May 2020 It’s the last day of the virtual Woad & Wool tour and time to leave the castle where Federica, Martha’s righthand woman, has looked after us so well. Don’t be too sad. There’s one more adventure awaiting you at Arezzo. We have a virtual visit to a painting restoration studio. It was recommended to me by the woman who also told me about the wool museum at Stia. Before my first visit in 2017 I had no idea of how you restore ancient paintings. The work is detailed and painstaking, but also exciting. I’ve visited three times and the women, who call themselves Art Angels, have always been working on a polyptych of 13th-century wooden panels painted by Pietro Lorenzetti, the older but less famous brother of Ambrogio, whose 'Allegory of Good and Bad Government' you might have seen in Siena. Marzia shows you the techniques they use to uncover the original painting. The good news is that they finally finished! The opening was scheduled for 17 April, but had to be postponed due to Covid-19. I wonder what they’ll be working on next year. And now it’s time for virtual hugs and kisses (allowed under social distancing rules) before we scatter to further travels and home. If I’ve whetted your appetite for Tastes & Textiles tours, head on over to my Tastes & Textiles web page to find out more. You’ll find dates for tours in 2020 and 2021. There are still places on the Wine to Dye For tour starting on 15 September 2020. If you’re interested, let me know. I’m not requiring a deposit until we’re all more certain about the possibilities for travel this year.

By Alison Goldberger In February we took off from our base in Tuscany to head to Emilia (the northwestern part of Emilia-Romagna). This region of Italy is particularly famous for not one, but two delicious types of salumi— Prosciutto di Parma and Mortadella di Bologna! This is why a group of eager students joined us to learn how to make these incredible products for themselves on our Advanced Salumi Course Bologna-Parma. During our induction we dove right into WHY we learn here and discussed artisanal production vs la Grande Industria. We met passionate farmers Giorgio & Claudia Bonacini at their farm, Il Grifo, near Reggio-Emilia. They are the definition of artisanal production. As we toured the farm where they rear Mora Romagnola pigs we heard about how they keep the whole production cycle at home and how they farm their 65 hectares biodynamically. They showed us the Modena cut, how they make salami, mortadella and the method for salting whole pieces. We also had the chance to inject a coscia (leg) with flavoured brine to make prosciutto cotto, but we didn’t have time to cook it. We think it would have tasted absolutely wonderful though! As soon as you ask Giorgio a question, he grabs a pen and sheet of paper and starts illustrating what he's talking about. We sometimes joke that we'll mount an art exhibition of his drawings! One of the parts of the course the students found really interesting was sitting around a table with him and learning how fermentation works. Giorgio loves the science behind curing and fermenting and this passion really rubbed off on our students! We also visited the Brianti family where Aldo and his son Luca rear free-range Nero di Parma pigs and Piemontese cattle on their organic farm. The guys gave us a run-down on a range of salumi typical of Parma—with a break to enjoy Sunday lunch with the family! Here’s a special piece of salumi by the Brianti’s, Fiocco di Santa Lucia. The photo on the front is Luca’s youngest daughter Marika. The fiocco is usually made from one of the leg muscles, but the Brianti’s have started curing one of the shoulder muscles, which they are also calling fiocco. It means ‘ribbon’, so a muscle that is longer than it is wide! Classic prosciutto di Parma was taught by Maurizio Cavalli. He and his family cure and age the Brianti’s prosciutto. In addition to prosciutto, they also produce coppa, culatello, culaccio and fiocchetto. It’s not all about salumi on the course though. We love to give our guests a real taste of the particular parts of Italy we visit. So we also paid a visit to Acetaia del Cristo where we learned all about the production of aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena DOP. Yes, it requires all those words to distinguish the true balsamic vinegar, which takes 12 years to be ready to bottle, from the aceto balsamico IGP, which takes only three months. We tasted it too of course—and discovered for ourselves the huge differences between the two!

Phew! If this has whetted your interest, take a look at our website for more information. And sign up to our newsletter to be the first to know the dates for 2021! |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed