|

Yesterday I took three generations of women to Vitalina’s dairy to learn to make ricotta and then to Beatrice Salvi’s hotel for a lesson in baking a traditional Garfagnana ricotta pie. You can’t make ricotta unless you make cheese first, so the added bonus was they learned to make goat’s milk cheese too. Before we arrived Vitalina had spent 2 hours milking 70 of her goats. She heated 60 litres of unpasteurised milk to blood temperature and added rennet. By the time we arrived, the milk proteins had coagulated to a gel and were ready for Liz, one of the guests of Sapori e Saperi, to have a go at cutting it to separate the curds and whey. Vitalina showed Maggie and Abby how to gather the curd which turned out to be harder than they thought, but they had fun feeling around for the curd at the bottom of Vitalina’s grandfather’s tinned copper pot. Vitalina learned from her grandfather and father and makes goat’s milk cheese and ricotta twice a day. After a little experience it’s really very easy. Notice that the curd is white but the liquid in the pan is yellow. That’s the colour of whey. Now the ricotta lesson begins. Vitalina turns the burner on high to start ‘recooking’ the whey. Ricotta means recooked and it can only be made from the whey. That’s why you have to get all the cheese curds out before you can make it. And by the way, almost all the fat comes out with the curds. While the whey is heating up, Maggie helps Vitalina press the remaining whey out of the cheese and Vitalina adds the whey to the pot. When the whey gets near boiling, the albumin protein molecules in the whey denature, which means they open up to expose their connection points so they can attach to other molecules to form white strands, just like when you boil an egg and the previously clear egg white turns to solid white. The white strands are ricotta. Luckily they float so you don’t have to plunge your arms into boiling whey. You just skim them off the top and layer them gently in the ricotta mould. Vitalina gives us some warm ricotta to taste. Everyone exclaims in unison: ‘Delicious! It’s nothing like the ricotta we buy in the States. This is so much better.’ Since ricotta is virtually fat free, they’re also bewildered as to why in the States there are two types of ricotta: full fat and fat free. I’m bewildered too and cynically guess it’s a marketing ploy. If anyone knows the answer, please leave a comment. Clutching our precious ricotta we go to lunch at L’Altana, my favourite restaurant in Barga. The cooking is excellent, but what I love about it is that the staff are equally good. One of our group is coeliac, and as soon as I tell our waitress, she goes off and comes back with a menu on which the items without gluten are marked. Since the menu changes daily, she’s done it specially for us. Then we walk to Villa Moorings Hotel where the owner, Beatrice Salvi, teaches us to use our ricotta in the traditional Garfagnana torta squisita, which means ‘very delicious pie’. First we make pasta frolla, a sweet pastry made of flour, egg, sugar, baking powder and melted butter. It’s the basis of most pastry in our area. The eggs come from Beatrice’s father’s farm. The yolks are deep orange, nearly red, and the whites are yellow and thick. The filling is made of ricotta, eggs, sugar, chocolate chips and a little Sassolino, an anise-flavoured liqueur. Goat ricotta is ideal for filling ravioli, but Beatrice and I were worried that it would be too strong for the pie, and Beatrice had bought some industrial cow ricotta just in case. Everyone tasted both of them except Beatrice. She said she didn’t like ricotta! I’m afraid I’m a bit of a bully when it comes to tasting, and finally she took a tiny spoonful of our goat ricotta. I wish I’d got a photo of the smile on her face. The industrial ricotta was a tasteless paste by comparison. We used our artisan ricotta, and the torta squisita, topped with a thin meringue, was truly delicious.

0 Comments

How many salamis are hanging here? There’s no prize for guessing, because I haven’t a clue. I was too tired to count. Ismaele Turri, the butcher, guessed they contained about 100 kg (220 lb) of pork. I wouldn’t be surprised. It seemed as if we’d never finish filling pig’s intestines: I’d put another length tied at one end on the stuffer and then grasp the crank and turn it clockwise while Ismaele gyrated the sack slightly as it filled, saying ‘Boh’ when I was to stop and hold the open end of the sack as he tied it three times very tightly so as not to allow in any air. Another length of intestine, more turns of the crank, another ‘Boh’ and another closing of the end. After about 15, the routine changed. I used a small tool that looked like a green plastic doorknob with needles stuck into one side to prick the salami all over, after which I massaged it vigorously to compact the meat and press the air out and shoved it over to Ismaele to tie tightly like a corset producing an hourglass shape and further expelling air, as it no doubt did to the women who used to wear them. Then they were ready for hanging from the broomstick to drip and dry. They’ll remain there from 7 to 10 days until Ismaele’s experience tells him the skins feel dry enough to be sure they have begun to dry right into the centre of the salami at which point he’ll move them to his maturing cellar under his restaurant. I went to visit Ismaele at his farm in Pieve Fosciana to see whether he’d be a suitable addition to the salumi (cured pork) course I organize for pig rearers, butchers and chefs. During the courses I’d watched Italian butchers making salami, but I hadn’t done it myself, and I only helped this time because Ismaele had had the crazy idea to turn two whole pigs into salami in honour of my visit. His assistant Donatella had to return to her young children after lunch, leaving me to fill her shoes. As the regiment of salamis grew, Ismaele and I passed the time talking about the value of old breeds of pig, the flavour of the meat that comes through in the salami if you don’t use preservatives (which aren’t necessary), how people have forgotten what real food tastes like in these days of chemical additives and much else. We agreed we could offer a sausage-making session and lunch in his restaurant for amateurs who want to produce a good Italian sausage at a fraction of the price you pay at the deli. For the professionals, he offered to allow them to make their own salami at his place. That clinched his place on the course, because I was realizing that I hadn’t truly understood the process despite the number of times I’d watched it and written down the percentages of salt and spices and the temperature and humidity for drying. It’s good to be reminded of what I want my guests to experience on my adventures.

All winter I’ve been banned from taking clients to visit one of my favourite cheesemakers because they were rebuilding the dairy. When you arrived at the old dairy you entered a shabby sitting room with an old table in the centre, along one wall a lumpy sofa, usually occupied by one of the farm cats, and along another an old chestnut-wood sideboard. It was dingy, but welcoming. The walls were decorated with black-and-white photographs of the family, showing grandfather and his sons posed outside the barn, and a poster listing the cheeses they used to produce. Since granddad died, they’d narrowed the range to fresh pecorino and ricotta made from the milk of their 400 handsome black Massese sheep. The cheesemaking took place behind in a space no larger than a corridor. Four large gas burners sat on the floor on the right and a narrow stainless steel draining-shelf with an upturned rim was fixed to the white tiled wall on the left. Giuliana and her daughter-in-law Maria Rosa took turns making the pecorino in a large aluminium pot, warming the milk on a burner, cutting the curd with a wooden stick and bending almost double to gather up the chopped-up curd into a lump after it had sunk to the bottom of the pot. Although there was barely enough room to turn around, each pecorino-sized lump was put into a plastic mould on the stainless steel shelf behind to allow the whey to drain and run into a plastic bucket on the floor at the far end of the shelf. Then they’d make ricotta by reheating the whey in battered copper cauldrons on the same burners on the ground. It was back-breaking work, and I spent the winter imagining the new large, more convenient dairy with the burners at a more comfortable height and more space to move about in. Today I went to see it. The front wall of the sitting room had been knocked down and replaced by a shop window. From the yard, I could see inside a chill counter filled with cheeses, and shelves affixed to the side walls stacked with honey, grappa and some kitsch stuffed animals. The photos had gone. A window had been inserted into the back wall of this new shop through which I glimpsed the enlarged dairy full of gleaming elephantine stainless-steel vats. Maria Rosa was standing at one on some portable steps, since the vat is too tall for her to operate from the ground. She beckoned me in and, as I entered, I realised she was peering intently at a thermometer immersed in the milk that filled the vat. I commented that I’d never seen her or Giuliana use a thermometer before. She explained that with this new container that heated the milk by circulating hot water in its double walls, she had lost her sense of the temperature. While we waited for the milk to coagulate, she listed the benefits of the new system. Before they only had the capacity to make half their milk into cheese; they sold the other half which brought in less income than cheese. Besides that, now they have a larger temperature-controlled storeroom, and instead of selling all the pecorino fresh, they’ve started maturing some of it, which also adds value. Since they’re making more cheeses, they can branch out and reach new markets by flavouring the pecorino with walnuts, tomato, pepper, herbs and hay. I asked her whether she liked, for instance, the pecorino aged in hay. ‘No’, she admitted frankly. ‘It’s too dry’. But then added quickly, ‘Lots of people like it because they eat it with honey and jam’. During this conversation, Maria Rosa tested the curd four times to check whether it was ready to be cut. Previously the women had a sixth sense about when it was ready and only once had to test it a second time. When she finally decided it was ready, she pressed a button and a vertical frame strung with wires started to rotate inside the vat and cut the coagulated curd into small pieces. When she judged they were small enough, she hauled the free end of a large-diameter plastic hosepipe over to a two-metre square stainless steel box-table on legs and casters, which took up most of the centre of the room. She now pressed a red button on the vat and the cut curd and whey was pumped from the vat through the hosepipe into moulds in a frame in the box-table. She needed my help to redirect the awkward, heavy hosepipe to different areas. When all the curd was in the box, it had to be redistributed among the moulds which required wheeling the table away from the wall. Again it was too heavy for her to do on her own, as was the frame holding the moulds, which had to be lifted out after the moulds were full. Usually her daughter was around to help. I remembered when even old Giuliana could lift all the human-sized equipment by herself. Now Maria Rosa looked awkward as she worked, compared to the ease and grace she had displayed when working in the old cramped dairy. I observed that the new system seemed to distance her from the cheese so her senses were no longer in control, and she agreed. But she insisted that the flavour of the cheese is the same. When she gave me a taste, I didn’t tell her that it had a bitter taste that hadn’t been there before. And best of all, she assured me, Giuliana is glad not to have to make cheese any more. When I had arrived, Giuliana was taking down the laundry. I’d greeted her and asked how things were going. She’d replied, ‘In somma’, which usually means ‘Could be better’. Franca and Peppe have promised to take me porcini hunting as soon as the funghi ‘nascono’ (literally: are born) after the rains. Looking out my window onto the the main street in the village (steep and cobbled, no cars), I see Anna Rosa and Ebe carrying baskets full of plump multicoloured funghi. It’s time to visit Franca and Peppe to beg a place on their next foray into the chestnut woods.

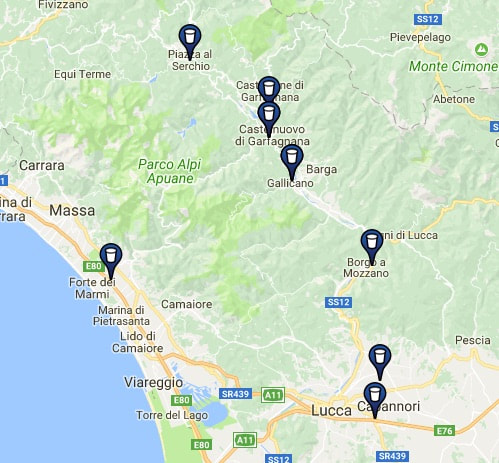

It’s 6.15 pm when I ring the doorbell, apprehensive that I might be interrupting dinner preparations, but Franca welcomes me with a beaming smile and makes space at the kitchen table — already crowded with her husband Peppe, their married son Marco, and Carlo, a builder friend and work colleague of Peppe’s. Having assured me that they’ll let me know about future porcini hunts (and the chestnut harvest, except that the chestnuts have only just started to drop, so it won’t be this week). Franca extracts a bottle of limoncello from the cupboard… Carlo turns it down (which I would have thought impolite) and out comes a bottle of single malt whiskey instead, which I happily accept as well, complimenting them on their well-stocked liquor cabinet. I wish I’d had time to ask how they’d got it, but Carlo is already saying that what he really likes is a good grappa, like the one he has from Friuli, north of Venice, with the scent of the grapes still in it. If this is a hint, it doesn’t send Franca back to the cupboard, and Carlo shifts to the wine of Friuli, which he also admires. Chianti is good too, he says, a real Chianti of course, not the ones that just say ‘Chianti’ on the label. Had we heard about the tanker they filled with water and sugar in Sicily? By the time it reached Milan, it had fermented. All the wine ‘manufacturers’ had to do was to add some red colouring and bottle it. They make a hefty profit, he claims, selling it at just €1,50 a litre. But if you know what goes into producing a good wine, you’ll know not to trust such a cheap bottle. Your neighbours’ wine is in a totally different category; you have firsthand evidence of it. Carlo thinks this year should be an excellent vintage here in Casabasciana. He tasted Giuliano’s grapes as he was passing last week with the newly harvested bunches. They were good and sweet after the hot, dry summer, but it remained to be seen whether the alcohol content would be 13% like last year’s or drop down to the 12% of 2007. I hope I’m invited to taste it, even though it will probably taste rough to me. The important thing that applies equally to fine wines and little local wines is that knowledge of the producer is what counts. It’s what keeps you from being made a fool of, and guarantees you get a genuine product. On the way back from a cooking lesson I’d arranged for clients, I’m crawling along at a Slow Food snail’s pace (no doubt infuriating the rush-hour drivers behind me) when I spy the little wooden hut I’m searching for. The hut — a kind of mini-barn — shelters a machine that dispenses unpasteurised milk almost straight from the cow and is part of an Italian rural development programme to shorten the supply chain and put consumers’ money directly into the pockets of farmers. The farmer tests every batch of milk with the lab equipment in his barn. Health and safety officials also check the milk regularly. There’s a website where you can find all the ‘mechanical cows’ in Italy. Here are the ones near me. A crowd of customers is gathered round, each hugging one or more empty glass bottles. It looks like happy hour at a bar, but as I get closer, I realise they’re waiting for the young farmer to clean and refill the ‘mechanical cow’. The landscape being more industrial than pastoral in this part of the Capannori, I ask the farmer how far away his farm is. He pulls me a few steps to one side and points through a gap in the buildings to his cow barn, about half a kilometre from us. Not many food miles required to fill the machine. Sensing a captive audience, he signals me over to his milk truck and opens the side door to reveal a secret cargo… Lying on the back seat is a large bunch of stringa. His own produce he proudly explains, harvested that afternoon for a customer who will be arriving any moment, so he regrets he can’t sell me any. ‘Stringa’ means ‘shoelace’ and refers to a small diameter green bean, grown only in the Lucca plain and nearby Versilia, that reaches 70–80 cm in length — more a bootlace, really. I explain that I organise gastronomic tours to visit small producers and ask whether I could bring some guests by to see his farm. He suggests I telephone next time I’m passing and he’ll show me around. He returns to his work, now filling the bottle dispenser with new glass bottles, for new customers or those who have forgotten theirs at home. By now the crowd has dispersed and I fill my own bottle. The milk costs 1 euro a litre and, for small consumers, you can buy it in units of 100ml, rather than having to buy a whole litre at once. It tastes intensely of milk, unlike the white liquid one buys at the supermarket, which costs €1,40. I say arrivederci, but he’s loath to lose a sympathetic ear. He looks indecisive, then makes up his mind, goes to the truck and steals a large handful of stringa from the bunch on the seat. ‘Here’, he says, ‘You know how to cook them, don’t you?’ ‘Yes, stew them with onions, garlic and tomato.’ ‘They’re delicious with rabbit, but only with my grandmother’s.’ He reminisces, ‘When I was a boy, I refused to eat rabbit if my mother bought it from the butcher. It didn’t have any flavour compared to my nonna’s. But she’s gone now, and I don’t have time to keep chickens and rabbits’, he continues wistfully. I promise to return soon, and bear my booty home to stew my stringa.

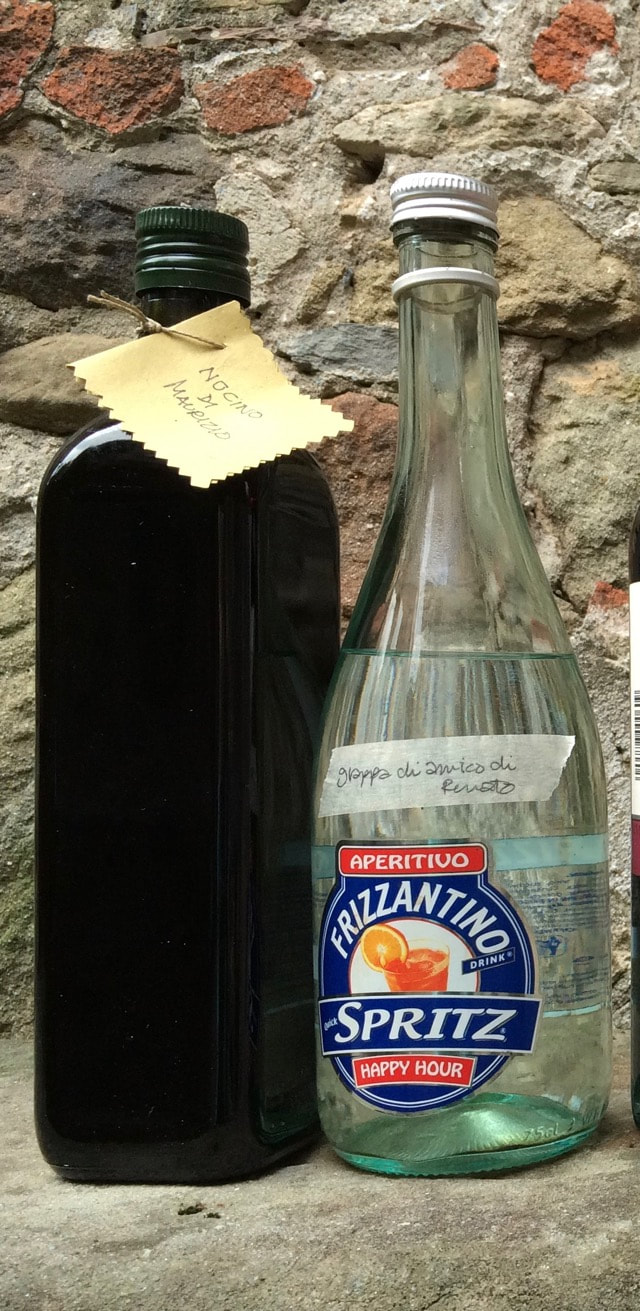

Last Thursday Cristina, who owns the restaurant the Antico Uliveto in Pozzi di Seravezza, and I walked up to the high pastures of the Alpi Apuane in northern Tuscany to visit a couple who are among the very few who still take their flock of sheep up to the mountain tops in summer. They live in a house powered only by a single solar panel and cook over an open fire in the large kitchen fireplace. Our lunch was composed almost entirely of their own produce. It included a porcupine that had been eating their squashes and melons and which Siria, the wife, had made into a delicious stew with their own tomatoes and a few olives brought up from the valley. When we arrived she was just beginning to fry some of the potatoes they grow, and soon had a huge pot of water hanging from a hook over the fire. As soon as it boiled, she added handfuls of maize flour (she apologised for it’s being last year’s — they’ve harvested this year’s maize but haven’t been down to have it ground) and we took turns stirring until it thickened into a soft polenta. It didn’t matter at all about it’s being a year old; it was Maranino maize and tasted like the corn it came from, unlike the tasteless polenta flour you can buy in a supermarket, or even most Italian delicatessens. We washed it all down with a very drinkable red wine made by the husband Pacifico. The meal ended with Siria’s pecorino cheese and sweet juicy plums from their orchard. After a cup of coffee and walnut liqueur (nocino), also made by them, Pacifico took us to see La Fannia, a beech tree at the top of the ridge that is said to be over 500 years old, and an abandoned silver mine, now the refuge of some rare red-bellied salamanders. We walked down as the sun set over the sea at Forte dei Marmi lighting up Monte Forato behind us. A day with Siria and Pacifico will definitely be on offer to gastronomic tour guests next summer.

September 2017: Since I wrote this blog, Siria and Pacifico decided they didn’t want visitors disturbing their peace. I don’t blame them, but it’s a loss to us. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed