|

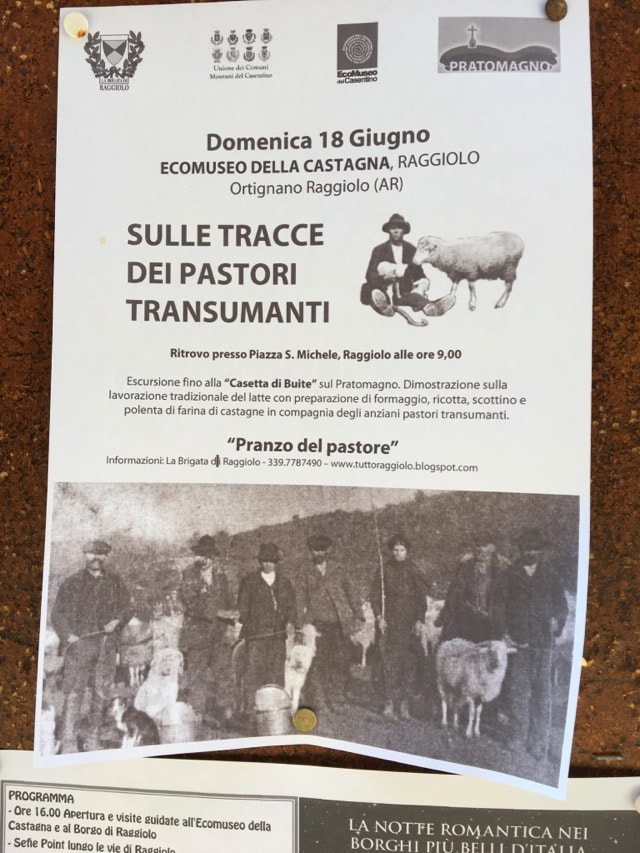

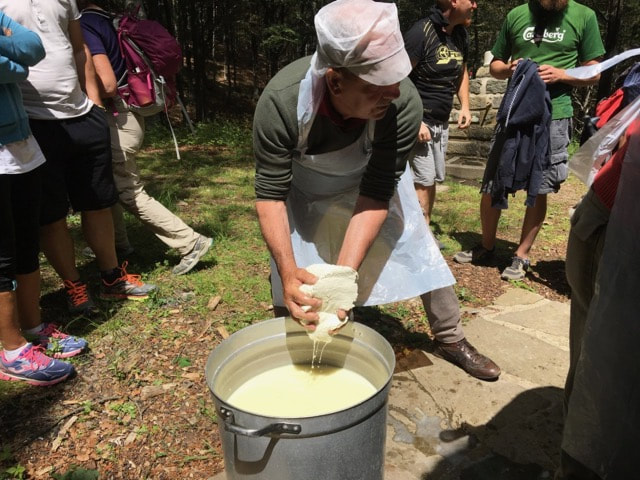

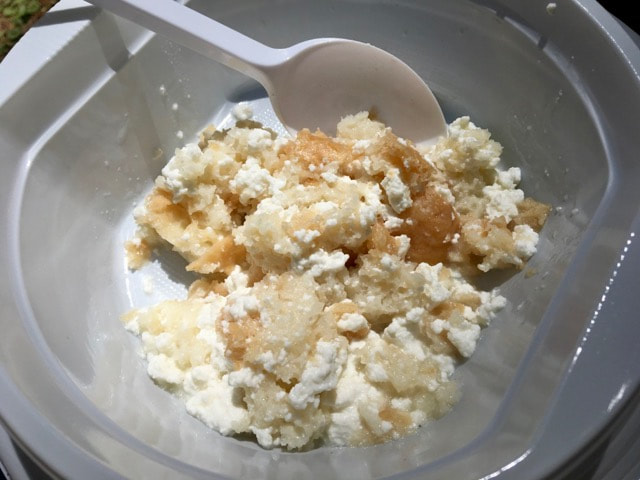

This is a true story about how cheese, history and a mountain village are inextricably entwined. It’s a long story because it goes back to Roman times. It has taken me 12 years even to begin to understand it. You probably know that pecorino is an Italian cheese made from sheep’s milk, derived from the word for sheep: pecora. On the contrary, it’s the rare person outside Italy who knows that transhumance refers to the seasonal rotation of flocks and herds between different pastures. Even more obscure is the connection between transhumance and Saint Michael Archangel. On 18 June a group of about 15 hikers, including me, stand expectantly in front of the church in the mountain village of Raggiolo, one of ‘The most beautiful towns in Italy’ (http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/project/raggiolo/). We aren’t waiting for the Archangel, but for our guide Paolo Schiatti to lead us along an ancient transhumance route to a former shepherd’s hut on the crest of the mountain above Raggiolo where we get to watch pecorino and ricotta making and have a shepherd’s lunch. I’ve watched many shepherds make cheese, and I wonder whether here near Pratomagno in the Casentino (east of Florence) they make it in the same way as in the Garfagnana. We learn from Paolo that the patron saint of shepherds is Saint Michael Archangel, but in Roman times the half-god, half-human Hercules was the favourite of pastoralists. According to Roman mythology he slew the fire-breathing monster Cacus who stole some of the cattle which he himself had stolen and was pasturing near Cacus’s cave. By one of those frequent transpositions of early Christianity, Hercules became the Archangel. In the New Testament Saint Michael defeats Satan to become a protector against the forces of evil. Two feast days a year are devoted to the Archangel: 8 May and 29 September. In early May the shepherds took their flocks up to the alpine pastures. At the end of September they brought them down. From early mediaeval times they built shrines to Saint Michael along the transhumance routes. In the days when they wintered on the Maremma, the coastal plain of Tuscany, it took a whole week to walk to the alpine pastures above Raggiolo. We’re lucky we only have a 3-hour walk ahead of us, and no sheep. The conversation about the Archangel might seem a distraction to a secular cheese lover wanting to know how Tuscan pecorino is made. Yet in Italy food and history are two facets of a common culture. The past spices the cuisine of today, and you can taste the difference between an industrial product made according to scientific principles and a traditional product made according to practices handed down through the generations. Paolo’s way of encouraging us is to say, ‘Siamo arrivati’ (we’ve arrived) when we still have over an hour of the steepest part of the trail to go. At around 1000 m (3280 ft) we pass suddenly from the chestnut wood into a beech forest. The muffled silence might remind you of a sanctuary. To me it seems dead compared to the luxuriant undergrowth of a chestnut wood. Casetta di Bùite I always tell my guests that cheese waits for no man or woman. We’ve dallied too long. The cheesemakers, Angelo and Dino Luddi, have already added the rennet to coagulate the curd. Nowadays they use veal rennet which they buy from the pharmacy. They don’t lament the change from lamb’s rennet which they prepared themselves from a lamb’s stomach, even though the pecorino is less piquant. They cut the curd using a wooden spino, an implement of the past. They use it not out of nostalgia but because it works well for the type of hard paste cheese they’re making. If there’s something modern that works better or is more convenient, they’re quick to adopt it, like the veal rennet. The past isn’t a prison. Dino’s job is pressing as much whey as possible from the curd. As we explain during our cheese course, in Italy where it was born, ricotta is NOT cheese. That’s official. It’s a dairy product. The casein proteins and much of the fat in the milk go into the cheese. The main protein left in the whey is albumin. The protein in egg white is also albumin. When you cook egg white, it solidifies, and that’s what happens to the albumin in whey when it gets to about 90˚C (194˚F). With two large pots of whey to heat, this is going to take a little while. We suddenly realise we’re starving, and wander off to find some lunch. The courses are ready in random order stretched out over three hours. Actually, most Tuscan Sunday lunches last this long. What I take to be antipasto consists of panini of prosciutto and salami with two wedges of pecorino on the side, all excellent. The pecorino has been supplied by Modesto Giovannuzzi. He tells me the sheep are at Castel Focognano (near Bibbiena), but doesn’t volunteer who made the cheese. I buy a wheel for the pecorino tournament at the end of our cheese course. I check in with the ricotta. It hasn’t begun forming yet, but Angelo is adding some milk to the pot. I object that traditional ricotta shouldn’t have milk added. He agrees. He’s doing it to increase the yield for the big crowd today. He adds quietly,’The ricotta is much finer and smoother with nothing added to the whey.’ He moves over to salt the upper side of the pecorino. Besides adding flavour, the salt slows down the lactic acid bacteria so the cheese doesn’t become too acidic and also helps draw whey out of the cheese—essential if you want to mature it for several months. Around the corner of the hut, Modesto and his son Andrea are now busy making polenta dolce, a porridge made with chestnut flour instead of cornmeal. It saved the people of the mountains, the Garfagnana as well Pratomagno, from starvation during the Second World War. Some people never want to eat it again, but for most it’s the ultimate comfort food. Drying the chestnuts, shelling them, sorting them and milling them is a winter occupation. You collect them after you’ve made your wine and before you begin harvesting your olives. In the days when the olive harvest took place at the end of November or even in December, your chestnut flour was already safely stowed in its chestnut-wood chests. A sudden commotion back around the corner signals that the ricotta strands are forming. Someone asks what the yield of ricotta is. Angelo doesn’t know, and I reply that for sheep’s milk it’s about 1.5%, but only half that for cow’s milk. Angelo says to me, almost accusingly, ‘You know the science, but we know the practice.’ He’s right. You could read every book about cheese and still not be able to make good cheese and ricotta. It’s the experience that counts, going back to your mother, uncle, grandmother, great-grandfather, and right back to your Roman ancestors and Hercules. You could fill a small cookbook with the Tuscan recipes for stale bread: zuppa, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro, aqua cotta to name just a few; and scottina, a shepherd’s dish. After skimming off the ricotta, the remaining liquid is called scotta. Around me it’s mostly fed to the farm animals, although some people say it’s a refreshing drink and a good broth for soup. To make scottina, you leave some of the ricotta in the scotta and ladle it over the bread. As we descend Paolo has an answer to every question I can throw at him and more. He tells me about how they preserved the chestnut flour by packing it into chestnut-wood chests to exclude the air. It was so tightly packed that you could cut it into blocks with a knife to take out the amount you needed. By summer it was a bit tired. To refresh it, they put it in a wood-fired oven until it turned dark brown and had an entirely different flavour. The conversation wanders to art history, politics, the problem of depopulation of rural villages like theirs and mine. Most people in the group have something to contribute. They own their history in a way I’ve never encountered outside Italy. Thank you Raggiolo for a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating day.

You can learn about Tuscan cheese and experience for yourself our cheesemakers’ strong sense of their history on our Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course: https://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/theory--practice-of-italian-cheese.html

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed