|

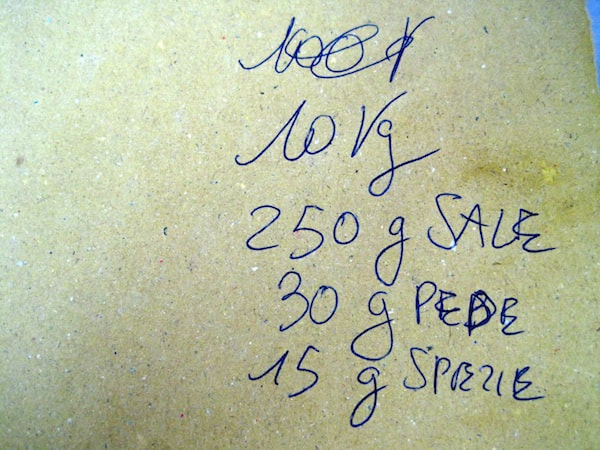

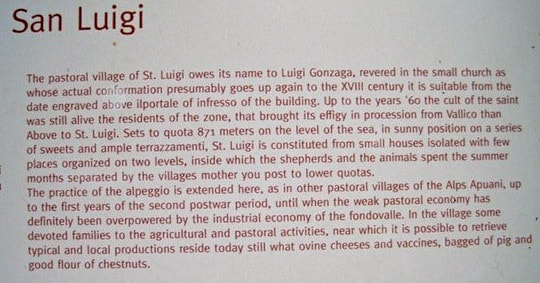

I spent from last Thursday to Sunday elbow deep in pork: whole pig, half pig, shoulder of pig, belly of pig, leg of pig, trotters, back fat and heads of pig. It was the fourth Advanced Salumi Course that I’ve organised for professional pig breeders, chefs and butchers, as well as keen amateurs. I never realised how many closet salami makers there are out there. Thursday afternoon we begin with a 3-hour introduction to salumi, the Italian word that describes the whole exquisite array of pink, red and white cured pork that adorns the counters of Italian delicatessens. This theoretical session is given by Giancarlo Russo, co-author of the Slow Food guide Salumi d’Italia and consultant on meat to Slow Food Italy. He designed the course for me and helped me find the norcini, specialist pork butchers, who teach the hands-on sessions. Thursday evening we have the best meal of the course at Gabriella Lazzarini’s home. She loves to cook seafood dishes and buys her fish from family fishing boats at the pier in Viareggio, near Camaiore where we stay the first night at the beautiful Villa Lombardi. This time she has prepared four antipasti including an unbelievably delicious stewed squid on creamy polenta. The first course is homemade pasta with a red mullet sauce followed by two second courses, of which one is the typical frittura viareggina, fried mixed poor-man’s fish. Since it was live and jumping at 8.00 am that morning, each fish has its own intense flavour. We barely have room for the fresh winter fruit salad with wild blueberries preserved in alcohol, but we manage to stuff it in nevertheless. Friday morning we head to Massimo Bacci’s butcher shop and salumi laboratory in Montignoso. Massimo clearly loves sharing his craft with other people. He starts by teaching us which cuts of pork go into sausages and which into salami. He shows us how he grinds the meat; he shares his secret spice recipe with us and shows us how he infuses wine with garlic to add to the ground pork. We learn how to massage the meat and everyone gets a chance to try it. Like kneading bread, it takes practice to get the right movement of palms and fingers and to make sure all the meat gets to the right stickiness ready for stuffing into sausage or salami casings. Occasionally Massimo’s 81-year-old father pokes his head through the door in a lull between customers and corrects his 60-year-old son in something he’s demonstrating. Filling the casings is called insaccati in Italian, literally putting meat into sacks. A sign I found in the middle of the countryside gives the creative translation ‘bagged of pig’. Tying sausages the Italian way is a challenge. So as not to make a fool of myself, I usually watch and help Giancarlo interpret (none of the norcini speak English), but this time I had a go and didn’t do too badly. Everyone falls in love with the natural hemp string used, and my carry-on allowance on Ryanair is often used up taking it back to England to post to former students. The next nearly insurmountable challenge is tying salami. It has to be tight enough to press any remaining air out of the salami while not cutting the casing. Massimo has an elegant way of doing it, and under his patient tutelage everyone finally produces their own adequate example. Now we see the salami drying cupboard. Massimo uses a programmable one because he doesn’t have the ideal natural conditions to achieve 100% good results. After about 7–10 days in the cupboard, he moves the salami to a partially underground room with some ventilation. He can control the temperature and humidity, but rarely has to. Now the salami is left to mature for a minimum of two months for the small ones and a lot longer for the larger ones. It’s not an exact science, and Massimo pinches the salami to determine whether it’s firm enough yet. Eying his maturing salami, I imagine Massimo feels like I do when I’ve made a batch of marmalade and I gaze at the rows of gleaming jars. We still have more to learn from Massimo. He shows us how he hangs small cocktail sausages for 5–7 days for a wine bar that serves them raw as an antipasto. In fact, in Tuscany we all eat raw sausage, usually spread on crusty country bread. Pigs don’t have trichinosis in Italy, so it’s perfectly safe, but the idea doesn’t appeal to English and American participants. Bravely they taste a tiny bit and as soon as they find out how good it is, they always come back for more. Massimo’s other product is lardo, cured pork back fat. Massimo lives just below the marble quarries of Colonnata, renowned for its lardo, and he too packs his slabs of fat seasoned with salt, pepper and herbs into marble ‘coffins’. One is dated 1896. I read that when Mario Batali started making and serving lardo in New York, his waiters asked him what they should tell customers when they asked what it was. They were sure no one would order it if they said it was pork fat. Batali told them to say it was ‘white prosciutto’, and it seems to have worked. I ask people whether they eat butter on bread; a fine slice of lardo is no more fat than that and tastes just as good. By now it’s lunch time and we get to taste all Massimo’s salumi. The bread is a traditional sourdough made only at Vinca in the Lunigiana. Since Massimo is a wine connoisseur even the wine is special and different for each course. We buy some salumi and reluctantly tear ourselves away to get to our afternoon session with Fabio Nutini, a subject for another blog.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed