|

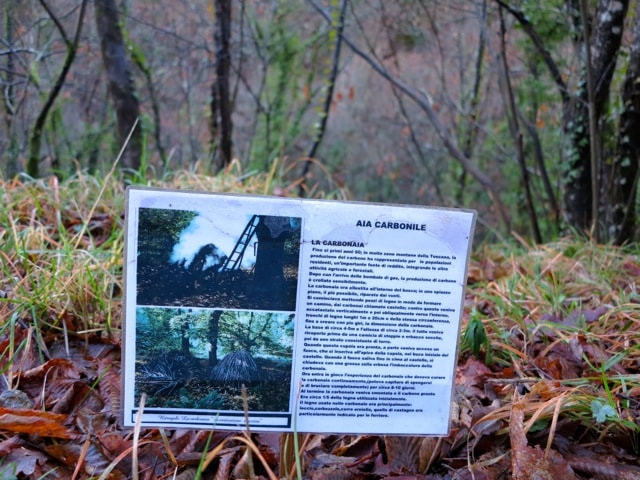

Is it better to visit the Presepe in Grotta (nativity scene in a cave) during the day or at night? We puzzle over this at lunch, which, as usual in Italy, goes on so enjoyably and so long that it’s dusk when we arrive at the bottom of the trail. The way is lit by a string of low-energy lightbulbs, which is just as well, since the trail is not for the faint of heart. When we finally reach the cave, our guide Stefano has no doubts that the only time to make the pilgrimage to the presepe is in the evening when you follow the lights, mimicking the Magi who followed the light of the star. I put this to the test when I come with other friends the next morning to repeat the journey in daylight. This time I’m more relaxed, not worried about getting to the cave before the rough, steep path disappears in shadowy gloom. We take time to appreciate the work put in by the speleological club, which had created a detailed nature trail along the path. This sign reads: ‘Botanical path. Le Campore: 600 m. Respect the woods. Wear hiking boots. Keep dogs on a lead. Carry an emergency lamp. Thank you for your patience’. Even at 11 am Carlo Galgani’s forge is in the shade. For three months during the winter the sun never reaches the bottom of the valley. The steps up to the cave at 600 meters are steep and uneven and were more than a little scary in the gloom of dusk the night before. The walk itself is an education. Trees and plants are identified along the way. Here we learn that around Lucca you’re allowed to forage for wild asparagus only between 10 February and 20 May, and each person may pick just thirty spears a year. This might be another activity to add to the foraging weekend I’m developing. Cultural history makes its appearance along the trail too. This sign explains that in the past there were many charcoal burners in the area. Carlo the blacksmith still uses charcoal from one of the few remaining charcoal burners. I’ve been meaning to try to visit him to find out whether I can bring guests to watch the process. As we near the cave, the trail gets even more arduous, but a laughing waterfall cheers us up the last set of rickety steps. Within the cave are pastoral tableaux staged with gesso figurines. Their manufacture made the fortune of many artisans in the Serchio Valley from the seventeenth century until the second world war, and their trade carried them as far afield as Scandinavia and Brazil. A family in my village still manufactures them, and I’m reminded that they offered to show me their small factory at the bottom of the hill, which I still haven’t gone to see. So many riches still to investigate. No one remembers bagpipes in this area. Perhaps this shepherd comes from the Abruzzo. Marco is on duty as the daytime guide. He tells us all the facts about the cave in a torrent of words with a flurry of hands. He says Stefano is the poetic guide and he’s the practical one. The cave has only one opening and slopes steeply down to an emerald lake at the bottom which is 7 or 8 metres deep in winter. There’s no life in it at all. Back outside Marco explains that all the gear has been ferried down by the cable car from the dirt road above the cave. We take this even more precipitous path up to the road, which we follow gently down to the valley and our car. The evening before we descend carefully down the lighted nature trail with some Italians who repeat rapturously, ‘Suggestivo, veramente suggestivo’; the English ‘full of atmosphere’ sounds lame, perhaps ‘charming’ or ‘romantic’ conveys our impressions better.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed