|

Butter isn’t an ingredient you’ll find in traditional Tuscan cuisine. The people north of the Apennine Mountains have cows, and they make butter. In Tuscany we have sheep. Their milk is used to produce pecorino cheese (the word for sheep is ‘pecora’ and the cheese made from their milk is ‘pecorino’).

In the Garfagnana we have a native all-purpose cow good for a bit of both milk and meat, which since the diffusion of modern specialised breeds and until very recently was considered good for nothing and nearly died out completely.

Families made a little butter which they used primarily in sweet dishes. In a local cookbook compiled by a woman of Lucca, out of 179 savoury recipes only four call for butter, three contain béchamel sauce and one is the recipe of a chef who had emigrated to New York. On the other hand, almost every single one contains extra-virgin olive oil. Out of 33 desserts, 23 use butter, mostly in the pasta frolla crust of pies.

Occasionally you come across a cow family, like the Nesti of Melo (Cutigliano) into which Daniela Pagliai married. (Women rarely take their husband’s surnames, although the children bear their father’s name.) Daniela had been her father’s shepherd since she was nine and in charge of making pecorino from the age of 14. When she married, she had to change gears. She now makes several types of cow’s milk cheese, yoghurt, gelato and butter. For more about Daniela, see my blog post: Like the Seasons: the Life of a Cheesemaker.

When I take my guests to her, I always buy some butter. It conforms to two of my rules when buying food: very few ingredients and nothing I can’t understand. Andrew Wilder of Unprocessed October calls it the Kitchen Test. Daniela’s butter contains one ingredient: panna, cream.

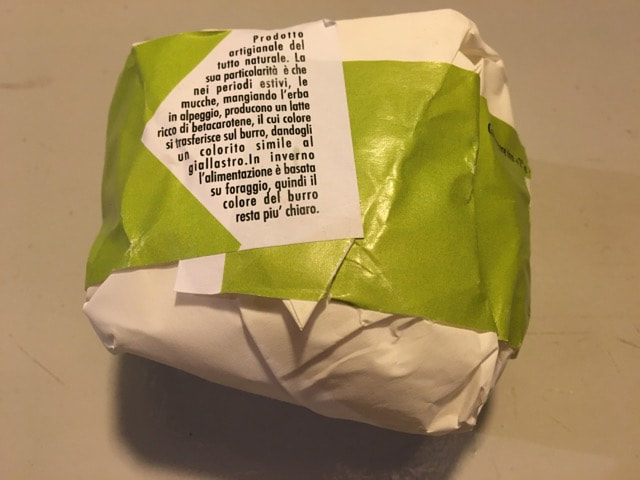

When I first started visiting her, butter was such a minor product that she didn’t even have a special label for it. She sold it in a ricotta wrapper. Now there’s not only a label, but also an informative essay.

Daniela says: ‘Completely natural artisan production. Its distinctiveness is that during the summer the cows graze in alpine pastures producing milk rich in betacarotene, whose colour transfers to the butter making it yellow. In winter, the feed is based on hay [not silage] and the butter is paler.’

They say that variety is the spice of life, and it’s often these tiny details that distinguish the truly artisan product from a standardised industrial one. Of course, nothing beats visiting the producer and checking their claims for yourself. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 25 September, 2016.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed