|

In England when I used to prepare historical feasts for Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music, I pined futilely for a cardoon farmer. Cardoons cropped up regularly in recipes of the 17th and 18th centuries. I finally persuaded a friend to grow them on his allotment, but he planted them next to his artichokes, which are nearly identical, and couldn’t remember which was which. In culinary terms it matters; you eat the flower of an artichoke, but the stem of a cardoon. I can’t find any advice on what would happen if you ate the stem of an artichoke, and I didn’t try. Cardoons are common in Italian shops and markets from November to February. Although they are completely unrelated, they look like giant celery but surprise with a flavour of artichoke hearts. The heads come in two shapes, depending on how they’re grown: straight stalks which are called cardi, and curved ones called gobbi. Gobbo means ‘hunchback’, and touching an amulet of a gobbo is said to bring good fortune. Whichever the shape, the cultivation and preparation of cardoons is fiddly. During their last month in the field, the stems are blanched like celery, by piling up the earth or tying straw or paper around them so they lose their chlorophyl and become creamy white. If you’re growing them gobbo-style, you bend them in half before covering them with soil. In the kitchen you de-string them, cut them into chunks and boil them in acidulated water to keep them from rusting. They’re good eaten hot simply with a drizzle of this year’s extra-virgin olive oil. In the Abruzzo a traditional Christmas lunch begins with a soup of cardoons and meatballs. I’ve recently tried a Lucchese recipe for using up leftover bollito (boiled beef): infuse olive oil with garlic and sage leaves over a low heat, add chunks of boiled cardoons and sauté until they start to brown, add the boiled beef cut into cubes, stir well, deglaze the pan with white wine, add a few tinned tomatoes (not tasteless winter tomatoes) and simmer for 15 minutes. As long as you go light on the tomatoes, the flavours balance each other perfectly. Nutritionally cardoons are star players. They are said to have a fortifying and bracing effect on the stomach, protect the liver, reduce cholesterol and blood sugar levels. Who knows, maybe they’re the elixir of youth.

There’s an old variety called cardo gobbo of Nizza Monferrato from the province of Asti in Piedmont. Being on the brink of disappearance, Slow Food has recognised it as a presidium. It grows on sandy soil with no fertilisers, chemical treatments or irrigation. Sown in May, by September the tall luxuriant stalks are ready to be bent over and covered with soil. The Slow Food website describes the plant dramatically attempting to liberate itself to get to the light. In the process of its struggles, it swells up and turns pure white. Once harvested and cleaned, it’s the only cardoon that can be eaten raw, and is an indispensable ingredient of bagna cauda, the typical Piemontese warm sauce based on garlic, extra-virgin olive oil and anchovies. Continuing the purple prose, ‘It’s not merely a dish but a convivial ritual. Simmering in the centre of the table in an earthware terrine, the diners dip the pieces of vegetable and bring them to their mouths, catching the oil on a chunk of bread.’ If you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Nizza Monferrato right now. Postscript: Some ingredients draw me to repeated research. I had written this piece before discovering that I also wrote about cardoons in January 2013: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/seasonal-eating-4-cardoons-2/

0 Comments

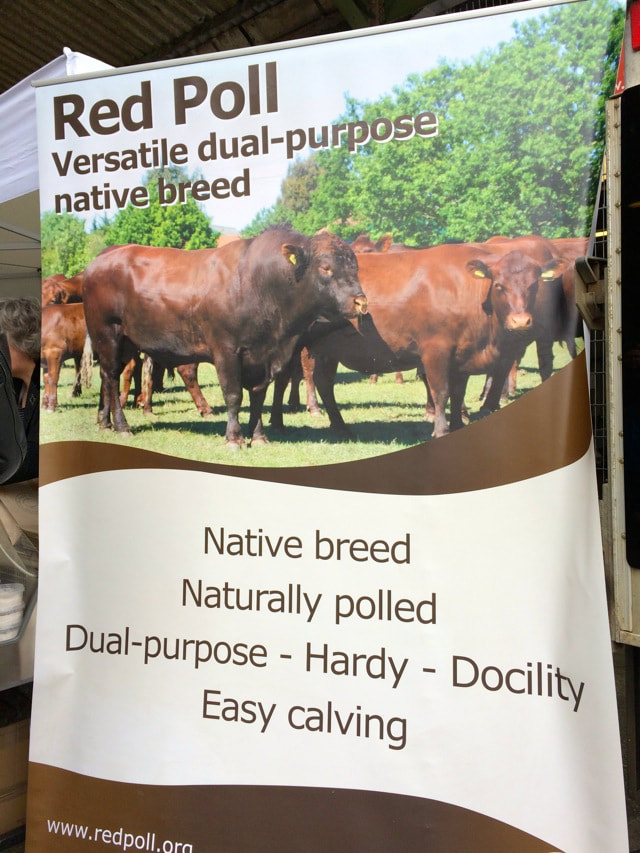

At the end of my Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I organise a little game: an England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament. This entails a trip back to the UK immediately before the course to go to Neal’s Yard Dairywhere I can always find a few excellent sheep cheeses. For the May course I did my shopping instead at the annual Artisan Cheese Fair at the old Cattle Market in Melton Mowbray. Although in its fifth year, I had never heard of it, but being featured by the Specialist Cheesemakers Association, I figured it would be worth the trip to Leicestershire, a direct train journey from Cambridge on the line to Birmingham, from where my friend Amanda joined me. It’s also one of the counties, along with Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, in which Stilton is allowed to be made. (Stilton, like Parmigiano Reggiano, is a registered product with a Protected Designation of Origin.) Unlike the market in Cambridge, which is today a ‘cattle market’ in name only, the one at Melton Mowbray still functions every Tuesday morning. I make a resolution to come back to witness the livestock auction. Turning to the entrance to the cheese fair opposite, we find the entrance fee is only £2 and admits you not only to the area populated with vendors’ stalls, but also to a series of cheese classes and tastings. The Red Poll Cattle Society was founded with the aim of preserving this versatile native breed. They note the long lactation period and ideal composition of the milk for cheesemaking. The British Isles are a land of cattle. Sheep these days are reared for meat, and it’s harder than I expected to find sheep’s milk cheese. These people from Canterbury can’t offer any. Amanda has served me excellent goat’s milk cheeses made by Pete Humphries of White Lake Cheeses in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, heart of cheddar country. At the far end of his stall, I glimpse a label saying ‘No Name Sheep Cheese’. He’s begun experimenting with sheep’s milk and this cheese is so new that he hasn’t come up with a name yet. It’s a bit young to compete with the mature pecorinos in the Italian team, but I hope it will make up in youthful energy for what it lacks in experience. Sharing a corner stall are two outstanding talents of British cheese, Jamie Montgomery who makes arguably the best cheddar in Britain, and Joe Schneider who makes Stichelton. Amanda and I found the farm on the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire for Joe and Randolph Hodgson of Neal’s Yard Dairy when they were setting up the dairy to produce what they expected to call ‘raw milk Stilton’, a return to how Stilton was made for centuries. However, due to an anomaly in the PDO definition of Stilton, it can only be made with pasteurised milk. One of the Dairy’s customers suggested Stichelton, an early name for the village of Stilton. Joe welcomed us to the stall and gave us a good chunk of this incomparable cheese to take home. Notice in the photo that the Stichelton isn’t excessively blue. The flavour of the blue mould doesn’t kill the flavour of the cheese. In search of two more sheep cheeses we crossed to another pavilion, passing a ukulele band and an artful display of Quickes Traditional Cheddar. Right at the entrance was the stall I needed. Carlow Farmhouse Cheese had brought several mature sheep’s milk cheeses to the fair. They don’t have their own website, and this one only admits to cow’s milk cheese. Their cheesemaker, Nadja, guided us through her samples. It was hard to choose, but I finally took some ‘pecorino-style’ and ‘cheddar-style’. Business done, we threaded our way through the crowds to a promising-looking pork pie stall. The pies were obviously raised by hand. The pastry is made by mixing hot melted lard with flour. It has to be exactly the right temperature to form it around the wooden moulds (see photo above)—not so hot that it burns your hands and not so cold that it cracks. The baker himself sells us our pie. He reminds me of my Italian artisan food producers when he talks about the natural ingredients he uses: the flour from a nearby windmill, pigs from a local farm and pig’s-foot jelly he makes himself. He’s sold 300 pies this morning and will be off soon to make another 300 for the next day’s fair. With a glass of incredibly strong cider, we settle down to lunch. I used to make pork pies myself, but these pies beat even my best. The crust was crunchy, the filling tasted like pork (not overpowered by spices and preservatives) and the jelly was well seasoned and firm without being rubbery. Melton Mowbray is a pretty market town, but even without its other attractions, it would be worth a pilgrimage for the King’s Road Bakery pork pies alone.

Italy is usually the clear winner of the pecorino match, but this time Ireland came out top in the opinion of our maestro Giancarlo Russo, a judge in international cheese competitions. Young ‘No Name’ was a big hit too with several of the course participants. Santa Zita’s mummy lies in a glass case in a side chapel at the Basilica of San Frediano in Lucca. Despite her cadaverous face and bony hands, she looks fresh and almost pretty in the blue dress and white apron of a serving girl. She wasn’t one of those martyred saints canonised for suffering a gruesome death in defence of their faith, such as Saint Lawrence who is said to have been grilled alive. Zita (c. 1212–1272) was a humble and hardworking servant, which earned her the affection of the aristocratic family for whom she worked. What they didn’t know was that at the end of each day she went to the kitchen, stealthily wrapped any leftover bread in her apron and distributed it to the poor. The other servants, being jealous of the high regard paid her by the nobleman, decided to get their own back by telling him Zita was stealing from his household. He could hardly believe it, but one evening as she was leaving the house with her apron bulging, he stepped out of the shadows and challenged her to show him what she was hiding. The girl quickly replied it was only some flowers, and was greatly surprised when forced to open the apron to discover it was indeed filled with flowers. Bernardo Strozzi (c. 1581–1644) captured the moment here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zita#/media/File:ThemiracleofStZita.jpg. Her position in the household was safe and Lucca ever since has had an excuse to fill its streets with flowers on her saint’s day of 27 April (or the nearest weekend). I’ve wanted to take part in this happy event for years, but until today I’ve either been away or it was raining, and the thought of a sea of umbrellas and drenched flowers wasn’t enticing. Today was grey, but not wet. Zita had been carried out of her side chapel to a place of honour in the nave. The Roman amphitheatre has undergone remakes so many times that there are only a few remnants of the Roman structure left. For part of the last century it was the site of the central market until that was moved to the Mercato del Carmine, leaving the piazza of the amphitheatre sad and empty except during the tourist season. Today the flower stalls showed how lively it must have been as a market.

A guest blog by Bob Schroeder Bob, his brother Dick and their friend Cullen Case came on my Advanced Salumi Course. They wanted to make the most of their visit and signed up for a truffle hunt on the Tuesday afternoon after the extension workshop. Bob gave me permission to republish his enthusiastic report to his family and friends back in the States. January 20, 2015 We went truffle hunting today. Lots of fun. Our guide actually trains dogs. He took Guy Fieri of Food Network fame on a hunt. Thanks, Bob!

In case you don’t know, truffles can be found all year long. Although the white Italian and black Périgord truffles are the stars, they’re all good and well worth tasting. We have seven edible ones in Tuscany. After the hunt, we go back to Riccardo’s home for a truffle feast cooked by his wife Amanda. We sit in their kitchen sipping prosecco with the antipasti and get to be part of the family. Tobacco? Smoking? Well, yes, responsible smoking. Nothing promiscuous, please. If you drink fine wine to enhance a meal, you’ll understand: this tour is about connoisseurship. It’s also about Tuscan history, cultural traditions, craftsmanship, and the many sublime products of Tuscany. Even though I don’t smoke, designing this new tour has been fascinating. All the people I take you to visit on my tours are Italian, but this is the first time an Italian has helped me with the creation of a tour. Antonella Giusti works for the Tuscan tourist bureau and is a member of Slow Food and of the Congrega dei Fumatori Indipendenti, the Society of Independent Smokers. (The word ‘congrega’ is also used for a coven of witches, and perhaps that’s why I’m bewitched by the tour.)

To read more about all the exciting things you can do on it, go to my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/tuscan-cigar-tour/ and look at the details of the tour at Tuscan Cigar. ‘Garfagnana Dove Il Tempo Non Corre’ is the motto printed on aprons sold by the tourist office in Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. It means literally, ‘Garfagnana where time doesn’t run’. We might say, ‘where time stands still’. In fact, it creeps along slowly. I’ve just reread a piece by Rebecca Solnit in the London Review of Books (29 August 2013) in which she reflects on some of the effects our electronic age have had on our experience of time: the interruptions to our concentration, the fragmentation of our solitude and relationships. She wonders how far we will allow big corporations to shatter our lives. Will we all be wearing Google glasses with continuous pop-up messages reminding us of practicalities while causing us to forget to ‘contemplate the essential mysteries of the universe and the oneness of things’? Then she muses: ‘I wonder sometimes if there will be a revolt against the quality of time the new technologies have brought us… Or perhaps there already has been, in a small, quiet way. The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn’t food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn’t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes and labour, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken.’ Reading this I realise it’s that wholeness I see in the producers to whom I take my clients: an immersion and satisfaction in what they do. It’s not that they don’t have to work hard or that they don’t have troubles, but that doing something from start to finish, from sowing to harvest, from slaughter to salami, from fibre to fabric, for themselves, their families and their communities produces a contentment way beyond the monetary value of their work. I can think of so many examples it’s hard to know where to start or stop. …in a wood-fired oven he built himself heated with wood he chopped himself. He didn’t grow the wheat, but he does grow farro and corn. The farm is an agriturismo which he and his wife Cinzia run. And he has a bar a short walk from the farm. Paolo Magazzini is another unhurried multi-tasker. He’s a farro and beef cattle farmer. He fertilises his fields with the manure of the cattle. He ploughs, plants with his own seed corn, harvests and pearls the farro. He provides the pearling service for about a dozen other farmers. Paolo is also the village baker, carrying on his mother’s trade. His recipe includes his farro flour and his own potatoes. From her smile, I wonder if she’s thinking about the beautiful finished articles he weaves. Schoolchildren come to her workshop to learn about the history of their families and Lucca in the silk trade. Gino will carry the business forward with a smile into the next generation. What more could any parent hope for? …in his forge powered only by water. It takes considerable inner fortitude to resist the health and safety inspectors who want her to use stainless steel. Andrea is never short of time when he can spend it with customers who he feeds with his latest artisan food finds. He dreams up new recipes when he comes to check his beer in the middle of the night. …and the long hours he spends in the woods with his dog infuse his family and work life too. The wholeness of my producers’ lives floods over to envelop my driver Andrea Paganelli and me.

This sequence of photos taken at the monastery La Certosa di Calci (Pisa) speaks for itself. If you want to know more about my exploration of the Monti Pisani, click here to read my blog ‘Ring Around the Pisan Mountains’ on the Slow Travel Tour website. Photos courtesy of Klaus Falbe-Hansen.

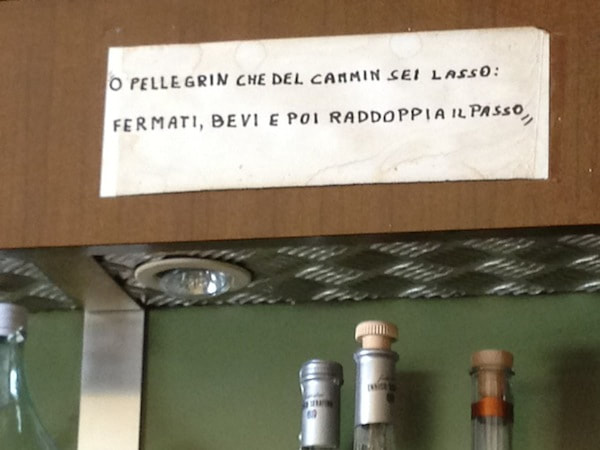

Full blog at: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/ring-around-the-pisan-mountains/ A couple of Thursday evenings ago I wrote a to-do list for Friday. The first item on the list was to pick up some leaflets at Topo Gigio, the bar-trattoria in Fabbriche di Casabasciana, the village at the bottom of my hill. The leaflets advertised a concert on Sunday for the benefit of the centre for the elderly at Casabasciana, which I was helping to organise. Considering the length of my list, all the things I wanted to get done before the weekend, the sensible thing would have been to hop in my car and drive the 3.8 km (2.4 mi). But it was a warm, not too hot, sunny day, and I hadn’t walked the mulattiera in ages. People in the village used to walk down it to school or work and back up again at lunch time every day. It seemed a bit feeble not to do it. I strapped my pennato lucchese, a Lucca-style billhook, around my waist and invited my friend Penny to accompany me with her secateurs. Mulattiera translates as ‘mule track’, but this makes it sound a paltry dirt path. In fact, the mulattiere (plural) were the super highways of the past, often many metres wide, surfaced in rounded cobbles or flat paving slabs, with stone-lined drainage channels at the sides or down the centre. Where necessary they were stepped. In mountainous areas like mine, they ran along ridges, usually just below the crest. Although they frequently crossed streams and small rivers, it was at the top where the water course was narrow and presented no great obstacle even in the rainy season. They descended to the valleys of major rivers only where absolutely necessary to arrive at a destination on the other side of the river. I’m not sure how old the roads in the Garfagnana are. It’s known that the Roman Consul M Claudio Marcello had the Via Claudia or Clodia Nova built in the 2nd century AD, and it’s likely that it followed an Etruscan road and possibly even earlier routes. The mulattiera that links Casabasciana with the valley is said to be mediaeval, but that’s the date people always attach to anything old. It’s about 4 metres wide and forms the main street in the village, descends about 100 m below the village and splits in two, the left fork diving steeply down to the pieve, the old romanesque parish church, and then continues to Sala, a hamlet of about 15 houses, which is linked by another mulattiera to the Liegora River which runs into the Lima River to the right. The other branch carries on straight down to the Lima, along which Fabbriche di Casabasciana is strung out. I’ve learned from my neighbours that upkeep of the mulattiera was the responsibility of each family through whose property it passed. In the ’60s the present-day car road was built, and since then the mulattiera has been used less and less by the locals. Only the sections used by woodsmen, hunters of wild mushrooms and wild boar, and horse riders (mostly tourists) are now maintained, and even these denizens of the forest tend to favour newer dirt roads suitable for 4×4 vehicles. It’s to us stranieri, who arrive with the notion of nature as a setting for recreation instead of work, that the task of cleaning the mulattiere now falls. Penny and I set off at about 9.30. We hacked, slashed and clipped our way to the bottom by around noon. Some parts of the road had been cleared but others were thick with elder and acacia saplings intertwined with clematis (old man’s beard) and brambles. It was particularly galling to find that one household had cut their land down to within a metre of the mulattiera and hadn’t been civic-minded enough to cut that stretch of the mulattiera as well. At Topo Gigio, arms scratched and bleeding, we bragged about our feat to the men playing cards or arriving for lunch, and taunted them by asking where they had been when needed. ‘O pilgrim, weary of your journey: stop, drink and then redouble your pace.’ Restored by the excellent worker’s lunch, I collected the leaflets and we set off back up the mulattiera. Even though uphill, it was much easier going this time.

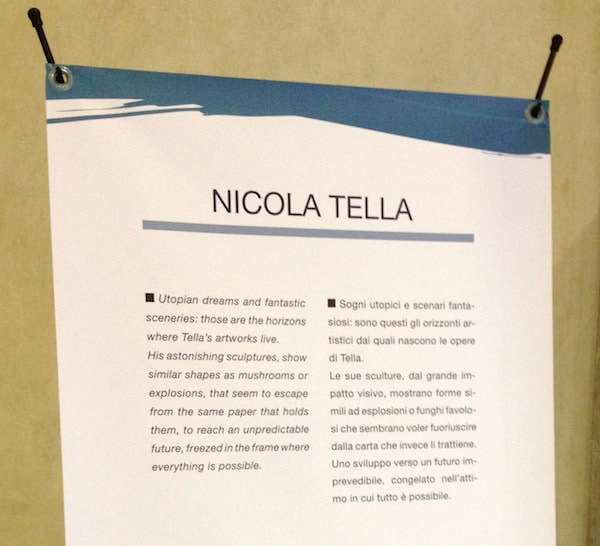

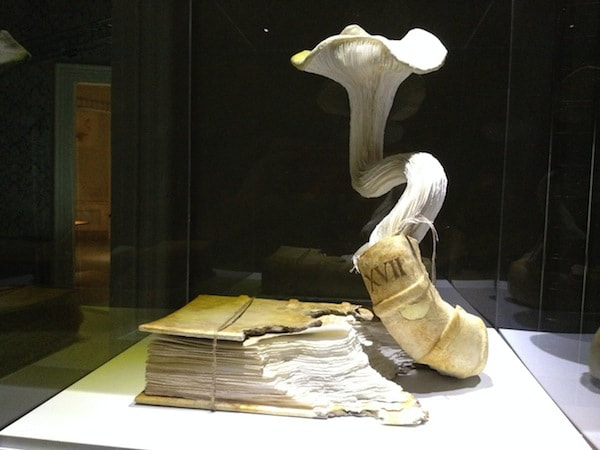

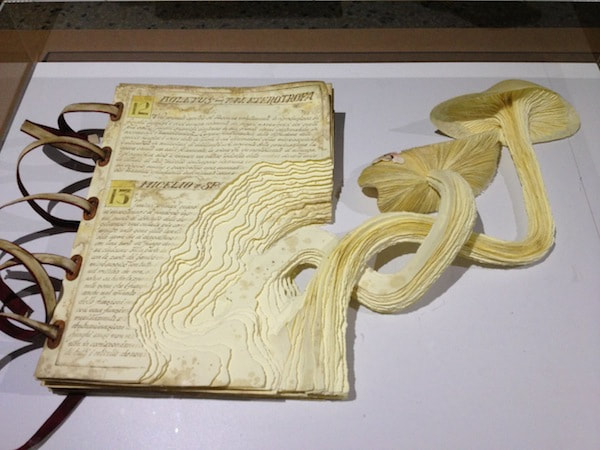

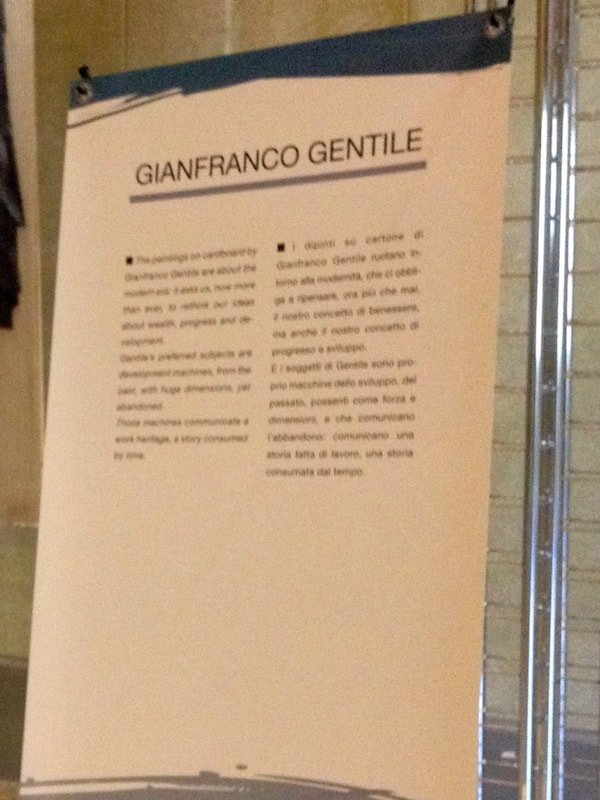

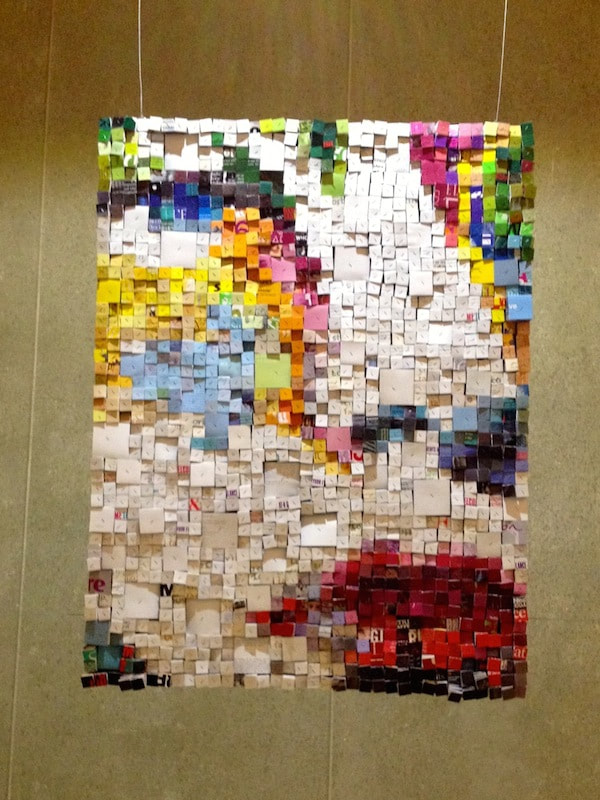

If anyone knows of a volunteer work group skilled at repairing cobbled roads, please get in touch with me at [email protected]. They’ll receive warm hospitality at Casabasciana. I know summer is here when I walk around Lucca in July and am confronted by larger-than-life paper sculptures: a phantom forest in Piazza San Frediano (1), a mythological armoured horse (2) under the loggia of the Palazzo Pretoria on the corner of Piazza San Michele, a surrealist right-side-up pear that morphs into an upside-down head up on the walls. The rules of the biennial international paper festival stipulate that all the materials used by the artists must be recycled. Sustainable environmental issues underly the themes of each festival. This suits Lucca. The province produces 80 per cent of Italy’s household paper (including Lu-paper) and 40% of its packaging and corrugated cardboard; and it’s Italy’s number one exporter of paper. Old, mostly derelict paper mills ornament many small valleys. Nowadays the main Serchio River Valley is lined with ugly modern mills which I used to consider a blot on the landscape. They became bearable, even desirable, when I realised that they’re major providers of employment in the valley, and serve to keep families together and stem depopulation of rural villages. This year I noticed an indoor exhibition entitled ‘Identità Liquide’ at Real Collegio, behind San Frediano. The most picturesque way to arrive is by parking in the free car park on the ring road outside the city walls and walking in through the passageway under the walls, coming out into the piazza in front of the Collegio. The ground floor of the cloisters were furnished with attractive corrugated cardboard chairs and tables and an entirely functional table football game made of paper, in addition to an exhibition of paper creations by school children. The grand high-ceilinged rooms of the upper floor were ideal galleries for a number of different international artists. Here’s a walk through some of them. Cartasia is over for this year. If you’re planning a trip to Lucca, put July 2016 in your diary now.

For more information about Cartasia, Biennale d’Arte Contemporanea: http://www.cartasia.it/en/biennial/presentation

Participants on the Advanced Salumi Course work with three norcini (specialist pork butchers) in three different parts of Tuscany. Recipes and methods change every 20 km, depending on regional variations and family traditions. If people stay for the extension workshop, they experience a fourth point of view with another family. They learn to make authentic Tuscan salami, prosciutto, and several other air-dried and cooked pork products. One of the lesser known of these are ciccioli, or grassetti as they’re called in the Garfagnana. Grassetti are the crispy residue of producing lard, much used in the past for frying and baking, especially in mountainous areas at altitudes where olive trees are less well adapted than the pig. The process entails cutting pork back fat (without the skin) into cubes… …and rendering it over a low heat until the pieces are brown. Then the pieces of hot fat are put in a press to squeeze out as much liquid fat as possible. The resulting pork chips are salted and drained on absorbent paper. They’re more addictive than salted peanuts, and chefs who attend the course realise immediately their potential as bar snacks. Gina Piazza (whose husband Kirby Piazza took most of the photos in last week’s blog ‘Like the Seasons: the Life of a Cheesemaker’) came on the course in March and sent me this report in early June: We had a press made by a welder friend and from 2 pounds of back fat we came up with a handful of ciccioli—but they’re amazing and I did it just as Ismaele makes it. I have 12 pounds of fat on order so maybe next batch will yield at least a few pounds. Now I have tons of rendered fat! The Advanced Salumi Courses for winter 2014–15 are almost full with one place left on the November course and three places on the February course. For more details of the course see Advanced Salumi Course Tuscany

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed