|

Where you lay your head at night can make or break your holiday. Your accommodation seems a simple thing to choose. You go to Tripadvisor, read the reviews and make your booking. You’re looking for a bedroom with a comfortable bed, a bathroom, a decent continental breakfast, cleanliness and friendly attentive staff. That’s probably exactly what you’ll get; a secure place to retreat to after visiting the famous works of art and architecture in some of most beautiful cities in the world. But at the heart of every country are its citizens, people who live differently from you. By your second or third trip, you can begin to think about getting to know them. This is what my tours are about. I want my guests to experience how Italians live their everyday life, which is something you still can’t do on the internet. It’s a compulsive reason to travel to Italy. I seek total cultural immersion, and so I usually choose an agriturismo for my guests, farm accommodation in the countryside, often on the edge of a village. Each one has a character completely its own determined by the personality of the owners, the setting, the architecture of the farm buildings and the produce of the farm. Here are some examples from my part of Italy, the area around Lucca and the spectacularly beautiful Garfagnana. I didn’t choose Al Benefizio; it chose me. Early in my sojourn in Italy I was at an agricultural meeting near Barga, feeling totally out of my element, when two women approached me and introduced themselves in English. One was Francesca Buonagurelli, the owner and farmer at Al Benefizio, and she is one of the main reasons for staying at Al Benefizio.

To read more about my favourite agriturismi around Lucca and the Garfagnana, please go to the full blog at Slow Travel Tours.

0 Comments

This week I got into a Fiat Panda 4×4 that turned out to be a time machine. The precise date to which it took me was 1969, but it could easily have been a couple of centuries earlier. Renato, the butcher and shopkeeper of my village Casabasciana, wanted to take me somewhere hidden. He knows I like walking in the wilderness, and thought this place would appeal to me, but wouldn’t reveal any more. We fixed Thursday afternoon, and I gathered my equally curious and appreciative friends Lone, Klaus and Tove to accompany us. Crammed into the Panda, we drove down the hill to the Lima Valley and turned right toward Abetone and Renato’s home town of Popiglio. Opposite the road to Lucchio, before Popiglio, we turned left into a gravel lane where Renato’s cousin Giuliano was waiting for us with his Panda 4×4. We divided ourselves between the two cars and bounced and wound up the eroded track, passing an occasional farm building. Just when it seemed we couldn’t go any higher, we reached the end of the road and the farmstead where Renato’s and Giuliano’s mothers and Giuliano himself were born. The sky was a uniform grey that day which added to the mood of desolation. The buildings sat on a narrow terrace, with stalls and pigsty beneath the house on the downhill side and the main door at the back. Numbers 1 and 2 must have been the buildings we passed on the way up. Giuliano opens the main door and to our right is the kitchen, focal point of a farmhouse. There are almost too many things to take in, objects signifying a different way of living. The family tries to keep the place in good repair, but it’s becoming more and more difficult. I’ve seen these burners in many old houses. You put coals from the hearth in the iron boxes and a trivet on top on which to rest the pot. The bottoms of the boxes are gratings that allow the ash to drop through and you remove it through the square holes beneath. The bedrooms are on the upper floor. Renato explains that this object was made from thin strips of chestnut wood. You hung a pot of hot coals on the hook inside at the apex and placed it under the covers as a bed warmer. We all giggle at the idea of a priest in the bed. In the background another model of ‘priest’, and in the foreground a tool to hold a skein of yarn while you wound it into a ball. The upstairs landing, like the kitchen, was another ethnographic museum. Giuliano’s father and grandfather were charcoal burners. There was a mountain cable car for hauling heavy goods up to the house. The tour of the main house concluded, we went to see the rest of the buildings. At the far end of the courtyard the door on the right opened into the much smaller house where Renato’s mother was born. Renato asked if we could guess why they left the courtyard covered with weeds. Because the pavement was so beautiful that if anyone saw it, they’d be up there with crow bars in an instant. The metato was the building in which chestnuts were put (‘mettere’ means ‘to put’) to dry on a slatted ceiling above a smouldering fire before being shelled, sorted and taken to the miller to be ground into flour. Back in the house we had seen some of the other tools required for the later stages. When the earthquake of 1920 caused landslides that covered several villages, the lower walls of houses were reinforced with these stone buttresses, just like a mediaeval fort, one of which we could just see across the Lima valley. Above the tiny village clinging onto the wooded slope are the remains of a fortress, part of Lucca’s late mediaeval line of defence against the Florentines. There was an almost unwelcome surprise. Adjoining the far end of the house was another house, owned by other people from Popiglio. They had brought it right up to date, including a television aerial. I wanted to see where the charcoal pile used to be. We drove back down the road a few hundred metres where we were greeted by more spectacular views. We know Vico Pancellorum well because of its restaurant Buca di Baldabò, one of our favourites in the area. On the spot where the charcoal used to be produced was a strange orchid. It has no chlorophyll, but is a saprophyte which feeds on rotting vegetation with the help of a symbiotic fungus.

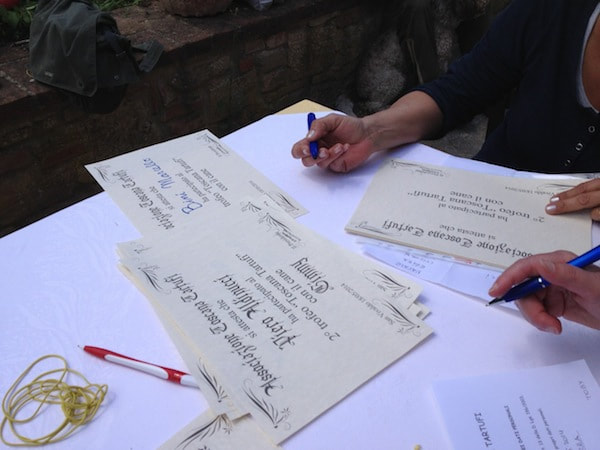

As we drove away, we learned the sad subtext to the visit. The family had concluded they had to sell the house. Their children have no interest in it, and since Prime Minister Monti introduced more taxes for uninhabited buildings, it was becoming too much of a financial drain. Their 7 hectares (14 acres) of fields and woodland are also subject to taxes. The top half of the road is private and requires constant maintenance. But who would buy it? Do I know anyone? I’m just back from the second annual Tuscan truffle hound competition organised by Riccardo, my truffle hunter. The competition is about as exciting as a village cricket match without the beer tent. Very little happens, but it does have the merit of being easy to understand the rules, unlike cricket (at least for me). I used to listen occasionally to a cricket match on the radio enjoying the foreign language of the commentators. Truffle hunters also have their own language which seems to consist of one- or two-syllable utterances to which the dogs rarely listen. This video gives you some idea of the pace and mutterings. [vimeo]https://vimeo.com/95670529[/vimeo] If it’s not much of a spectator sport, at least it demonstrates the method used and patience needed to train a dog to be a good truffle hound. There are very few breeds that can’t excel, but you have to start the training when they’re just a few weeks old. Give them simple commands, teach them to retrieve a stick and eventually bury a plastic capsule with a fragment of truffle in it for the puppy to find—over and over and over again. Riccardo explains the psychology of training: dogs are pack animals and the man (I haven’t met a female truffle hunter yet) has to play the role of leader of the pack. Some men don’t have it in them. Others have figured out how to motivate their dogs to keep their noses to the ground. Riccardo and Teo demonstrate best form. Note his subtle hand movements. While not exactly electrifying, the location is beautiful and the camaraderie enjoyable. What better way to spend a sunny Sunday than chatting to friends while sitting on a stone wall in the shade of a pergola at San Vivaldo monastery. When the trials are finished, all the dogs and owners converge on the ring to retrieve the buried capsules. At this point a Franciscan friar emerges and surveys the scene. He gazes at the small square marked out on the lawn, shakes his head and states that surely in so small a space every dog would find every truffle. Meanwhile, the certificates are being prepared and the prize-giving begins. In 15th place, the man whose dog found none. No one’s a loser. In first place, a man no one knows. He wants to be notified of the next contest, but doesn’t understand what an email address is. What sets a Tuscan truffle hound competition apart from a cricket match is lunch. We drift into Il Focolare (‘the hearth’), a restaurant in the cellars of one wing of the monastery, for an abundant and well-cooked lunch. Riccardo and I have taken many guests on real truffle hunts (no plastic capsules) followed by a truffle lunch at Riccardo’s home (click November, but you can hunt truffles in almost any month). We’ve also designed an intensive truffle course, and soon we’ll have a truffle weekend on offer as well. Let me know if you’d like to be notified when it’s ready: [email protected].

The Garfagnana is unquestionably beautiful. It’s rugged mountains cloaked with green forests set it apart from the Tuscany of Chianti to the south and the Po Plain of Emilia over the Apennine Mountains to the east. But I could never understand what use it could possibly have been to the Dukes of Ferrara, the Este family. In 1429 Nicolò d’Este annexed the Garfagnana to his realm and for almost four centuries the Garfagnana remained under the Dukes, who defended it against the republics of Lucca and Florence. I searched the internet; I asked my city guide in Ferrara. It seemed never to have occurred to anyone to wonder why. Today I went to the Sagra della Minestrella di Gallicano. Minestrella is a soup of wild herbs and beans made only in Gallicano, a town of fewer than 4,000 people. Today it is the southernmost town in the Garfagnana. When the Garfagnana was under the rule of the Dukes of Este, Gallicano was the northernmost Lucchese stronghold (apart from the even smaller town of Castiglione di Garfagnana). Directly across the river in Barga the Florentines held sway. Surrounded by strong neighbours, Gallicano went its own culinary way. The plan of the day included an introduction to wild edible herbs, a walk (in the rain — not planned) identifying the edible herbs along the path to the Antica Trattoria dell’Eremita (Old Restaurant of the Hermitage), where we not only feasted on the legendary minestrella, but numerous other traditional dishes illustrating the use of wild herbs, not omitting the focaccia leva, a flatbread unique to Gallicano. The conversation turned time and again to the detailed history of the region and the extent to which it influenced agriculture and culinary tradition. Everyone seemed to be well versed in the history of the place. It was the symbolic and often the actual basis of their ownership of the land. I talked to Cesare, who had organised the event, about taking my clients to forage for edible herbs and use them to prepare a meal. He was agreeable, but cautioned that the activity wasn’t to be just about the identification of the plants, their recipes and flavours; it had to include their cultural history, what they meant to the families who ate them. Ivo Poli, who had given the lecture on the wild plants, gave me a lift back to my car. He lives in the next town north of Gallicano and had always been a Garfagnino (citizen of the Garfagnana). I asked him the question that had teased me for so long. It’s easy, he said, ‘We had the petroleum of the Renaissance: charcoal.’ I’d walked in the tree-covered mountains; I’d seen a charcoal burner at work; I’d watched the blacksmith Carlo Galgani beating iron in his charcoal fire; I’d been to a village that produced nothing but nails; but I’d lacked the historical glue to put them together. Far more important than nails and horseshoes, every ruler needed charcoal to smelt iron to make arms to defend his borders and subdue new territories. The village streets lined with grand houses with imposing doorways suddenly make sense as residences of the oil barons of their day.

Pasqua is Italian for Easter. Last year I went to Francesca Bonagurelli’s agriturismo Al Benefizio to join her family and friends for their typical Easter lunch. Queen of the day Francesca at the right edge of the photo nearest the kitchen, her daughter, her nephew, her cousin from Milan, her brother-in-law, her sister, her mother and her dear friend Marta. An antipasto consisting of the usual crostini and some olives didn’t prepare me for the surprises to come. The primo was something I’d never had before: gnocchi alla romana. Instead of the little potato cylinders, these circular cakes were made of semolino polenta to which egg yolks and parmigiano was added. And instead of boiling them, they were sprinkled with butter and more parmigiano and browned in the oven. Delicious! The secondo, roast beef, was accompanied by enough vegetables to please any of my clients, who are always asking, ‘Where are the vegetables?’ Here again there was a surprise: a vegetable looking like the hair of a punk angel who had dyed it bright green. It was Salsola soda, a saltwort that grows around Mediterranean coasts and is harvested between March and May. In Italian it’s called agretti or barba dei frati(monk’s beard—a punk monk?). Wikipedia tells me that it was important historically as a source of soda ash, one of the alkalis needed for soap and glass making. The clarity of cristalloglass from Murano depended upon soda ash. As a food it’s supposed to have a detoxifying effect. Just when we thought we would burst, the table was cleared, the cakes arrived and the spumante was uncorked. Naturally there was a colomba di Pasqua (Easter dove), a traditional Easter cake similar to panettone served at Christmas. Recently arrived from Naples was another novelty: the pastiera napoletana wrapped in its Easter finery. One legend reveals its origin. One night some fishermen’s wives left baskets of ricotta, candied fruit, wheat, eggs and orange flowers on the beach as an offering to the sea, so it would protect their husbands and bring them back safe and sound. The next morning, when they descended to the beach to greet their returning husbands, they discovered that the waves had mixed the ingredients, and in the baskets was a cake.

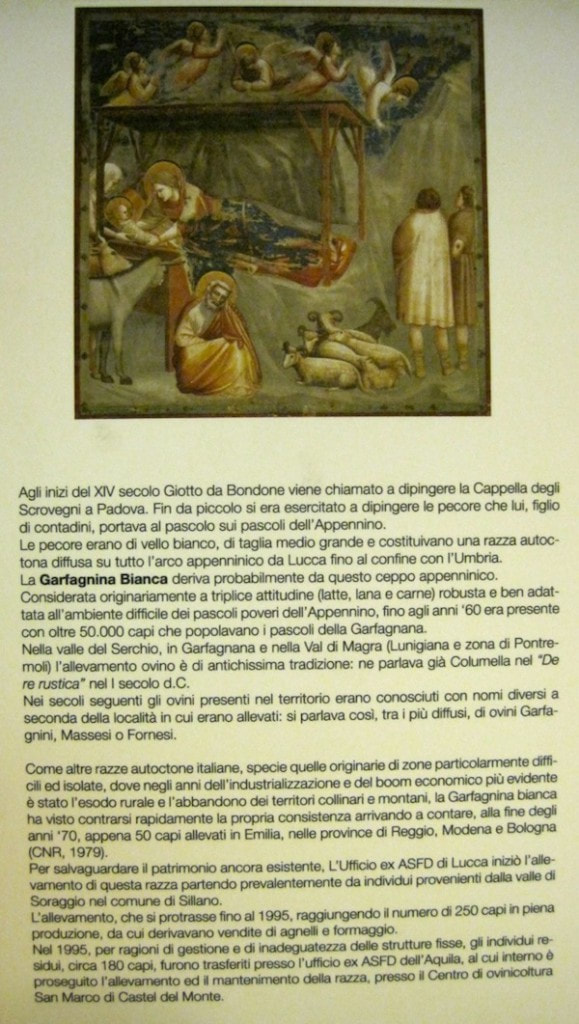

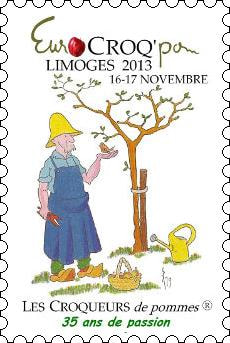

At noon on Wednesday 9 April in Florence, Dr Francesca Camilli of the Italian National Research Council will present a paper to the 1st European UNESCO-SCBD* Conference on ‘Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe’. Her paper is entitled: ‘The Garfagnana Model: exploitation of agricultural and cultural biodiversity for sustainable local development’. One of her prime examples will be Cerasa farm, a mountain paradise which is no secret to my clients who have written rapturously about their visits (here, here, here, and here May 2012). Mario, Gemma and their daughter Ombretta are a fundamental part of a project, overseen by the Germplasm Bank set up by the Comunità Montagna della Garfagnana (now the Unione dei Comuni), to preserve the indigenous Garfagnina Bianca sheep. If you’ve noticed some sheep lurking in the foreground of a nativity scene by Giotto, it could have been this breed, which was once common in the Apennine Mountains. Mario and the dogs look after the sheep. Gemma makes pecorino cheese and ricotta from their milk. Ombretta dyes their wool with natural dyes and has them knitted and woven into saleable products. Mario rears rams to sell to other farmers who want to join him in preserving the breed. Another strand of the Germplasm Bank project is the botanical station at Camporgiano. They have rescued dozens of indigenous varieties of fruit and vegetables. Besides being grown at the station, each variety has been entrusted to a custodian, a local farmer responsible for its propagation and preservation. I visited the station last year where the Director Dr Fabiana Fiorani explained their work. In 2013 the Garfagnana submitted several apple varieties to the European Pomological Exhibition at Limoges where it gained the distinction of ‘Custodian of Biodiversity’. Watch this space for the announcement that I can take you to the botanical station followed by a visit to one of the custodians and lunch in their home. The next opportunity to visit Cerasa is during the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June. The UNESCO conference lasts for three days, during which dozens of international experts deliver research papers. It could be a big yawn, but judging by some of the titles, I for one would be awake. For example, a paper by J. J. Boersma of Leiden University is intriguingly titled ‘Could the rewilding of Europe be seen as progress?’, with the implication that the answer is ‘yes’. To me the most interesting theme is that biodiversity of domesticated plants and animals appears closely connected to cultural diversity arising from the traditions and identity of a place. Finding the balance between tradition and modernity may be the virtuous path to sustainable rural development. The mere fact of an international conference organised by UNESCO on the topic of biodiversity and sustainable development raises hope that the planet will not be entirely subjugated to the interests of agri-business. A more local, but equally important action took place yesterday, also in Florence, when Slow Food organised a demonstration against the introduction of GM corn in Italy. Fingers crossed! Find out more: Joint Programme Between UNESCO and CBD, Convention on Biological Diversity, Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe Conference programme, Les Croqueurs de Pomme

*Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, based in Montreal, Canada Last week I wrote about getting to know my clients before they even arrive. Often our friendship continues after they leave. There’s the chef from Santa Barbara who came on a private tour in 2009. I visit her and her husband, and now their young daughter, every time I go to see my sister in Los Angeles. When I send a newsletter, it’s such a pleasure when previous clients reply filling me in on what they’ve been up to. And of course some people return for more tours and courses. Then there are the triumphs of participants on my courses. Stuart Busby, development chef for Laverstoke Park in Hampshire, England, came on the Advanced Salumi Course in February. Laverstoke Park is an organic-biodynamic farm based on the principle that our health depends on the food we eat. Stuart went straight back and, using their farm pork, made the soppressata (a type of head cheese) he had learned from Ismaele Turri on the course. I heard from him shortly afterwards: ‘I entered two products into the Charcuterie section of The Great Hampshire Sausage & Pie Competition last week. We were awarded a gold for the soppressata and the judges’ comments were “only one soppressata fan on the panel but he said it was faultless”! We also entered Organic Beef Biltong which won a gold award and also best overall Charcuterie product for Hampshire 2014.’ I phoned Ismaele excitedly who said he was very happy for Stuart. I expect he was also proud to have had such an able student. Soppressata is made from boiled pig’s head, and sometimes the offal is added too. It means something like ‘pressed from above’. After the hand-chopped meat is stuffed into a casing, weights are put on top and it’s left to cool overnight. Stuart himself added: ‘Great things can still be produced from the humble pig’s head with a little spice and a lot of love!’

By Gina Piazza and Heather Jarman One of the great pleasures of organising tours and courses is getting to know my clients. Often this happens during the initial phases of communication, even if people are booking a Small Group Tour or one of our Courses with Artisans for which the dates and programme are already fixed. People ask questions, I reply and we get to know each other. A wonderful example of this is the emails between Gina and me as she and her husband from California were preparing to come on the Advanced Salumi Course which is taking place right now. ME (during the previous course): The course is going well. We had a good day yesterday. But one man on this course is having problems understanding because he has never done any butchering and doesn’t know pig anatomy. This reminded me of you telling me that you didn’t have any butchering experience. I think you will get more out of the course if you at least do some reading up on the internet and maybe look at some diagrams of pig anatomy. GINA: I did help butcher a half hog just a few weeks ago!! I completely dissected the head and then helped saw it in half for roasting. I deboned the shoulder, cut rib chops, and trussed up a shoulder roast stuffed with garlic and herbs- it was fantastic!! After the course we bought an entire hog head and I made pig head pozole- I’ll send pics later but it took 2 days to complete and it was delicious! Had some friends over and made a party of it- See you in a few weeks! YAY! Ps…Is it raining a lot? ME: I’d never heard of pozole. Looked it up on the internet and got an ‘authentic’ recipe for pork shoulder and saying it takes 1 hour 45 minutes. Yours sounds much more authentic! Would love to see the photos. We’ve just had three whole days of sun!! GINA: We had to split the head in fourths to get it into 2 pots- Boiled it with herbs for 3.5 hours… …soaked hominy overnight then cooked all 2.5 pounds of it (dried white corn) for 3.5 hours, cut up 5 pounds of pork shoulder and boiled for 2 hours, then took 3 types of dried chilis and garlic charred them on an iron skillet, de-seed the chilis and soak the skins in hot water for 30 minutes. Blend garlic, chilis and chili water in a blender to make a paste that seasons the soup base. So you see, if I bought canned hominy, that would save time but taste horrible. I boiled and shredded the head one day… …and make everything else the next- the broth from the head is amazing!! We put some aside to add to both a ramen and a Cannellini bean soup- delicious. ME: Amazing!!! Your description and photos would be perfect as a guest blog on my blog. GINA: Let’s do it! AND, tonight I’m casing 20 pounds of farce for Sbriciolona salami to dry cure for 4 months- I’ll document that too. We’ve made Cotechino, Gaunciale, and Cacciatorini as well. ME: Great!! You’ll be able to teach the course by the time you arrive! GINA: The day began with lots of rain so it was a perfect time make salami! We didn’t even change from our pajamas! I prepared 20 pounds of pork leg and hog casing the night before, then proceeded to turn the casing inside out with the awesome trick of running the water through. I ground the pork to stuff into the 20 feet of hog casing for our final product of fifteen, 1 yard each Sbriciolona salami, that will air cure first for 4 days in the shed, then for four months in a temp and humidity controlled stripped out refrigerator. My husband, Kirby, also prepared 20 pounds of pork leg to make Cacciatori and spicy Italian sausage. I won’t bore you with the details of how we got to this point because in truth, our kitchen is small and tempers are short…..but, I’m still married and we poured a BIG glass of wine and toasted- to our salamis, that hopefully won’t crash down from the ceiling! THREE WEEKS LATER When Gina and Kirby arrived on the course we hugged and kissed on both cheeks like old friends! She’s excelling on the course. I’m eager to follow Gina and Kirby’s progress after the course, and I hope to visit them when I visit my sister in California.

By Penny Barry and Heather Jarman Penny writes about the opening of Bagni di Lucca’s celebration of women, and I add a few kitchen notes to the photos below. March 8th is International Women’s Day, commonly known in Italy as Festa delle Donne, or, as my husband and I affectionately call it, ‘Donni Day’. To commemorate the occasion Bagni di Lucca stages Omaggio delle Donne, a week-long series of events and exhibitions at the historic Casino at Ponte a Serraglio. This year it included an exhibition by women artists, a photographic exhibition, music and poetry recitals. There was also a display of kitchen equipment from the 1920s to ‘40s, but was this stereotyping the role women? I don’t think so because Italy is a country where food is appreciated by both sexes with an almost religious fervour and both the producers of good ingredients and the skills of cooks are venerated. I think the inclusion of vintage kitchen utensils is a positive feminist statement and a celebration of women’s importance in this country. Looking at the implements, it’s interesting to see how much has changed in the intervening years and to think about the origins of our modern kitchen gadgets. – Penny Barry The curved blade with wooden handles is a mezzaluna, which is still used to chop vegetables and herbs. It’s quick and efficient once you learn the technique of walking it rapidly from back to front of the chopping board, and it doesn’t reduce everything to a mush the way a food processor does. Since your hands are above the blade, children can safely help chop providing they follow a few simple rules which they learn on my family adventures. You can buy a mezzaluna in any kitchen shop in Lucca, but if you want a very special one, I’ll take you to the blacksmith Carlo Galgani, who makes them in his forge and adorns them with hand-turned olive-wood handles. Not some mediaeval torture implement nor 18th-century surgical forceps, but hinged iron plates for cooking necci (chestnut-flour crêpes) over a flame, originally the kitchen fire but nowadays a gas burner. They are readily available in ironmongers (hardware stores), and I bought a pair several years ago. You grease the hot plates with half a potato dipped in oil or lard, pour a small amount of batter in the centre of the bottom plate, close the top plate onto it, cook for a minute, turn them over and cook for another minute. Mine are so heavy that I had to have Penny and her husband come round to help me turn them over at half time. Testi are also made of terracotta, which you see at sagras in the Garfagnana. And just to show that testi are anything but sexist, men are as likely to be in charge of them as women. I don’t have one of these, because the butcher in Casabasciana does it for me.

– Heather Jarman I don’t do birthdays, but one year an Italian friend and I discovered we share the same birthday month of March and impulsively decided to throw a joint party at his vineyard. He had a plan to import to Lucca a great delicacy found only in Rome, where he and his partner used to live. It was just the season for puntarelle. I don’t have a photo and, photo police being what they are, I don’t dare steal one, but here’s a good one that shows you how it got the nickname ‘asparagus chicory’ (scroll down to the second photo and beware the intrusive pop-up ads). http://ricette.giallozafferano.it/Insalata-di-puntarelle-alla-romana.html Its Latin name is Cichorium intybus and it shares with the whole chicory family a pleasantly bitter flavour. The season is longer than I’d thought: it can be sown from August until December and harvested from December until April. It used to be cultivated only in Lazio and adjacent parts of Campania, but a fortnight ago I found it in the Casabasciana village shop. The heads look like the photo at this link. http://www.gentedelfud.it/prodotto/dettaglio/puntarelle-di-cicoria/ As I was buying one, Renato, the shop owner, asked me how I prepare it. As a salad, I replied, thinking back to the recipe in the River Cafe Cookbook Green, which includes celery, salted anchovies, peperoncino (chile pepper), oil and lemon juice. Since there are so few of us here in winter, there are no salted anchovies for sale in the shop so I bought a jar of them preserved in oil. What about the leaves, Renato persisted. I recognised the ‘waste not, want not’ tone of voice. I boil them like ordinary chicory and dress them with oil and lemon juice, I lied, while vowing to myself to convert it to the truth. A nod of approval from Renato showed I’d passed the test. Preparation of the salad is a little long-winded, because you have to remove the outer leaves and then separate the buds, the asparagus-like shoots, from the ample root and slice them lengthwise into thin strips, which you soak in iced water for at least an hour. This causes them to form pretty curls, like the radish flowers we used to make in the ‘70s, and draws out some of the bitterness. The first link in this blog gives the classic Roman recipe in which the crispy curls of puntarelle are dressed in an emulsion of garlic, anchovies under oil, olive oil and wine vinegar. Even if you don’t read Italian, the pictures are so clear that you should have no problem following the recipe. The River Cafe version is slightly more elaborate, the fate of most Italian recipes that emigrate to other countries, but is delicious nonetheless. Next year I’m going to try the Roman version.

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed