|

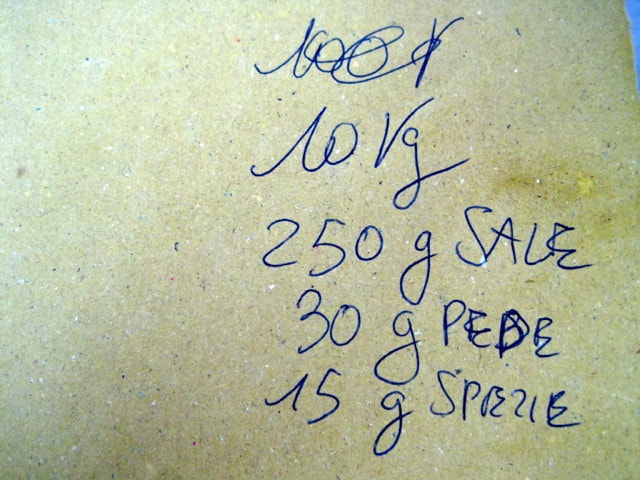

If your lifelong dream has been to stuff a pig in a sack, your moment has arrived. French charcuterie, Italian salumi, Spanish jamón and English cured meats are all the rage. Not only are gourmet hams and salamis hogging (sorry, I couldn’t resist) the cold counters at fashionable delicatessens and stylish online shops, but every farmers’ market boasts a stall or more selling artisan salami made from rare breed pork. Want to learn to butcher a pig, salt a pancetta? Just type ‘charcuterie course’ into Google and you get 2,360,000 results for courses from Dorset to Down Under by way of Denver. If you’re a butcher, chef or pig breeder wanting to make Italian salumi, your choice is more limited. Even though when you enter ‘salumi course’, you get 237,000 results, not many are designed for professionals. But the top four are and they’re us: the Saperi e Saperi Advanced Salumi Course. Everyone who comes tells me our course is unique: it’s aimed at food professionals; it takes place in Tuscany; it lasts for four days, short enough for a small-scale pig breeder to get away and long enough to cover the subject in depth; the price is moderate—you don’t have to sell the farm or the restaurant to come. In my opinion, what makes the greatest difference is that we’re in Italy. ‘We’ is course leader Giancarlo Russo, native Tuscan, and course organiser me, adoptive Tuscan. We know there’s no such thing as ‘Italian’ salumi, nor even ‘Tuscan’ salumi. Move 20 km and you find different styles and practices. We know if we use only one norcino to teach the course, participants will get a totally skewed idea of how salumi is made. They’ll think there are rigid rules, because each norcino is sure his method is best. Giancarlo is consultant to Slow Food on meat and contributor to the book Salumi d’Italia. He knows the vast range of salumi in Italy and that there’s no hope of covering all of it. What to do? We base the course in northwestern Tuscany and use three norcini more than 20 km apart. In his theoretical sessions Giancarlo covers some practices in other parts of Italy. We’ve chosen our norcini carefully. All of them are at least third generation butchers, having learned from grandparents and parents. They are true artisans. They are aiming at excellence, not a uniform product. They use the best maiale pesante (heavy pig of more than 155 kg) they can get, always Italian. They don’t use starters, sugar or milk powder. They use a small quantity of potassium nitrate (E252), never nitrites. They dry their salami either naturally or in a drying cupboard and mature their products in a natural cellar. They reveal all their secrets except the exact mix of spices, which is a family recipe. You’re encouraged to take photos and videos. They want you to go home and make good salumi. Otherwise, they’d be wasting their time. Our first norcino is Massimo Bacci from Versilia, the northern coastal plain of Tuscany. Massimo is a consummate salumi maker and a natural teacher. He’s clear and patient; he explains and demonstrates and allows you to tie a salami as many times as you need to get it right. Massimo explains the stages in drying and maturing, and he produces the best lardo I’ve ever tasted, using the same marble basins as in Colonnata, higher up the mountain from him. His 83-year-old dad pops in from the adjoining shop every 20 minutes to make sure his 60-year-old son is giving us the correct instructions. Their mortadella nostrale (a salami, not cooked like mortadella di Bologna) always comes first or second in the all-Italy artisan salami competition. From Versilia we speed down the autostrada to San Miniato, a town along the Arno River between Florence and Pisa, where we visit Maurizio and Simone Castaldi, two brothers who learned their art from their father and uncle. We first came to them so we could include the fennel-flavoured salami finocchiona in the course. The finocchiona zone lies between Florence and Arezzo, south of our other two norcini. During our first visit, we discovered that their strongest suit is the production of prosciutto, and we now include an in-depth study of prosciutto from salting to air drying. Now we head to our third norcino at Venturo farm in the Garfagnana, the mountainous area north of Lucca. We’re just over the Apennines from Parma and Modena in the Po Plain, so many of the products are the same. Ismaele Turri learned from his father, as well as working in a neighbour’s butcher shop from the age of 14. He’s a farmer and pig breeder. He slaughters two of his largest pigs in honour of our course. Participants are guided from the butchering of the pig to all the various typical salumi of the Garfagnana: prosciutto toscano, coppa, guanciale, pancetta, salami, cotechino, soppressata, biroldo (blood sausage) and a few other surprises. Since we allow no more than seven people on the course, there’s lots of time for hands-on practice. If you stay for the extension workshop on the Tuesday after the course, you watch a production run at the Rocchi family salumifico near Lucca. Their efficiency is a sight to behold. At the end of the course we ask for feedback, which Giancarlo and I use to improve the course to meet the needs of future food professionals. Even experienced butchers who already make salami tell us they learn a lot on the course. Last year a couple who came on our first course got their salami accepted by Harrods. We’re proud to be the launchpad for such successes.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed