|

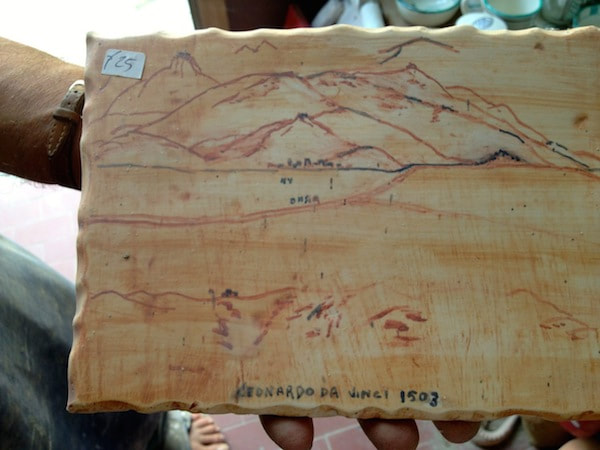

The Autumn in Tuscany tour is being revived for 2023! Here's a blog post to whet your appetite, it delves into some of the things we see on the tour. On top of Monte Serra stands a forest of telecommunication masts. Ugly as they are, they’ve often saved me from losing my way when traversing the Lucca plain on its tangle of threadlike roads. They’re a beacon for the organic olive estate where I take my guests to pick and press olives and which lies at the foot of the mountain. Monte Serra at 917 m (3008 ft) is the tallest peak in the rather puny chain called Monte Pisano (Pisan Mountains). Until a month ago all I knew about this clump of hills was that the ridge formed the boundary between the former republics of Lucca and Pisa, and that Lucca had lucked out by being on the east side which is rich in natural springs. The aqueduct built by Lorenzo Nottolini between 1823 and 1833 carried pure spring water to the drinking fountains of Lucca. (The same springs are now piped underground and the water is purified by ultraviolet light.) My truffle hunts around San Miniato, in the Province of Pisa, had shunted the Monte Pisano up my research list, because my route to the truffle woods runs along the old Via Sarzanese, an ancient pilgrimage path along their eastern base. The mountains arrived at the top of the list in August when I was looking for outings for friends, my willing guinea pigs on my exploratory forays. I’ve been three times, twice making an entire circuit of the mountains in an anti-clockwise direction, and once cutting through the middle to inspect the telecommunications masts up close. The masts probably won’t figure in future tours, but everything else definitely will. Here’s a brief preview of tours to come. Starting from Lucca on the old road to Pisa along the Serchio River, you merge into the faded grandeur of an earlier epoch. You slow your pace and almost believe your car is a horse-drawn carriage. Emerging at San Giuliano Terme with its five-star spa, you cross the newer road between Lucca and Pisa. Fields of reeds testify that you’re now on the floodplain of the Arno River as it meanders lazily from Florence to Pisa. At Campo you’re convinced that the only pine nut factory in Italy that carries out the whole process from harvest to clean nuts has gone out of business. It turns out that the ugly single-storey factory, discreetly hiding behind a row of houses, only opens between October and April while the nuts are being harvested, and the owner shows us the hibernating machinery. Pisan pine nuts are to be sought out, and the ones you can buy here are in a class of their own. Note to return in October; could be combined with the olive harvest and truffle hunts. Next stop the Certosa of Calci, a house of the cloistered monastic order of Carthusians founded by Saint Bruno in 1044 at Grande Chartreuse. When it was inhabited by monks, they lived in seclusion, but there was nothing ascetic about the architecture. Half the building is home to the Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa. Besides the new geological and cetacean galleries, you’ll be enchanted by the museum of a museum, the 19th-century eclectic displays preserved in their mahogany cases. It’s lunch time and the guide at the Certosa recommends Il Conventino at Tre Colle, a village with a church and a few houses near the top of a stream valley with a view to the sea. He knows his restaurants; it’s good enough to return a second time (and third and fourth). Continuing anti-clockwise around the base of the hills, you hurry through a chain of strip developments to San Giovanni alla Vena and the last remaining potter in a ceramic tradition going back to the Middle Ages. Here is the source of the ubiquitous green spatter ware I see in every ethnographic museum in Lucca Province, and which I’ve been trying to track down for years. After giving you time to tiptoe among the clutter and select a few pieces to buy, Guido sends you round the corner to two historical flood control buildings, one dating at least to the 14th century and the other from the 18th century. Due to Leonardo da Vinci’s successful deflection of the Arno, the once necessary floodgates now hold back only a tide of industrial waste. It’s a short drive to Vicopisano. Once the key to Pisa’s defences against Lucca and Florence, Leonardo’s engineering feat left it high, dry and useless. The castle designed by Brunelleschi has been saved the same fate by the dedicated guide Giovanni Fascetti, who has given it a spit and polish, and conducts a fascinating tour from the dungeons to the tower top. He isn’t always there, but now I’ve got his mobile phone number. Also not to be missed at Vicopisano is the Church of Santa Maria. Still half an hour till a respectable Italian dinner time. Venturing past the cemetery, a sign to Frantoio Vicopisano (Olive Press of Vicopisano) beckons. The tour by the enthusiastic owners lasts longer than you expected. Another note to come back in October during the olive harvest. An hour later you enter Paolo Ricci’s welcoming restaurant L’Osteria di Ceppato where the seafood tastes like a million euros but costs so little you wonder whether there’s a zero missing at the end of the bill. The aromas of the meat dishes on the neighbouring table presage another visit. Completing the ring, you arrive at Lucca on the Via Sarzanese. Just before crossing back into Lucca Province the huddle of houses named Caccialupi, ‘Hunt the wolves’, may raise a smile. Not an activity you’ll find on my tours.

This is all part of the Autumn in Tuscany tour, which will be taking place from 3-13 November, 2023! Find out more here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 7 September 2014.

0 Comments

Very few people I know have been to Sardinia. If they have, they went with the kids and stayed on the beach. If I ask people where in Italy they would like to go, Sardinia is rarely in their top 10. Yet it has so much to offer: Even I only went to Sardinia by accident. Some weavers who were coming on one of my Tastes & Textiles tours in Tuscany asked me to take them to visit a woman who weaves ‘sea silk’, the filaments of the beard of a sea mollusc. Reluctantly I agreed and hopped over from Pisa, only 50 minutes by plane to Cagliari, the capital of Sardinia. It wasn’t love at first sight. But, like people, I believe places merit more than a casual glance. Many reveal their treasures only to those who patiently dig below the surface. There’s no better way to get to know a place than to learn from the locals. Enter Antonio Arca. He was born in Alghero in northwestern Sardinia and moved to London in 2004, the same year I came to Lucca. His company Capo Caccia Fine Food imports the products he knows and loves from small, trustworthy suppliers. During one of my research trips to Sardinia, Antonio advised me to go to Sa Sartiglia festival in Oristano, in the west central part of the island. You can read about it here. I was travelling with friends who wanted to go to Cabras to see the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, but I was too engrossed in the festival. I was meeting farmers and family food producers at street stalls. One of these was Marcello Stara, a local rice farmer. I don’t know why I’m so excited by rice. Maybe it’s the flavour of good rice (not the bland quick-cook stuff) and its versatility in different cuisines from Asia to Italy. Maybe it’s the fact that it grows in water and required communal cooperation to provide the irrigation. Maybe it’s just how beautiful it looks in the field. In any case, I was already conjuring a tour to include Marcello and his rice during the harvest so we could find out how it’s processed and what freshly harvested rice tastes like. But one farmer doesn’t make a tour. I consulted Antonio. Did he know know other people in the area? Would he like to collaborate on a tour? Yes and yes. We planned a research trip together. First we needed a place to stay. For me it had to be an agriturismo (farm accommodation) so we would be investing in the rural economy. I found three suitable ones on the internet. Antonio chose L’Orto. Not only do they have enough private rooms with en suite baths, but they have a restaurant and dad is a fantastic cook. Everything local and perfectly cooked. We visited Marcello and his rice fields. He introduced us to Davide Orro and his family in the next village. Davide could almost be a tour in himself. He’s an enthusiastic winemaker and olive farmer and his sister Ester makes decorated festival bread. He planned our day: start picking olives, cure and bottle the olives, learn to make decorate bread with Ester. Lunch: bread, local cheeses and salumi, olives, wine. One of the grape varieties is known to have been grown in the area 3000 years ago. Davide suggested we go see Sandro Dessé. He’s even more versatile than the Orro family. You arrive at his farm and see a paddock of sheep and goats, one of donkeys and horses, pigs at the back and dinosaurs over to the side. Behind the pigs are fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Sandro is a practitioner of the circular economy. Not only does he produce the raw ingredients, but he processes them as well. There’s a small abattoir, a laboratory for curing pork, a cheese dairy and a kitchen for drying fruit and making pasta. His dining room seats 250 guests. Sandro’s wild, wide-eyed enthusiasm is contagious, but we can’t do everything in one visit. We must have a tour of the farm, and it would be fun to have a lesson making the delicious stuffed pasta called culurgiones, which we can eat for lunch along with Sandro’s many other products. Here we pick up the trail of some of Antonio’s friends. Paolo Lilliu, a butcher, who makes the salsiccia sarda, which you can cook when they’re fresh or air dry and eat like salami. On your morning with Paolo you’ll make your own, after which we’ll go to his friend Sandro Picchedda, a saffron and peperoncino (chili pepper) farmer for a barbecue and a traditional dessert made with saffron. Some other friends of Antonio introduced us to cowherd and cheesemaker Giuseppe Sanna who makes the Slow Food Presidium cheese casizolu from the milk of his own cows. He's willing to let you try your hand at forming the cheeses. My friends came back wide-eyed and enthusiastic about the Giganti di Mont’e Prama, bigger than life-size stone statues of warriors which probably date to around 800 BC. Having been an archaeologist, I had to see them too. Luckily they reside in the seaside town of Cabras, which is also a centre of bottarga production. We talked to several producers who told us about the technique for fishing the grey mullet, cleaning them and salting and curing the roe to make the much sought after and expensive delicacy bottarga. The gentle and generous Giovanni Spanu invited us into his production facility. The Giganti were even more impressive than I had imagined. They immediately became the mascots of the tour—little-known giants, the heroes of their land. Our living giants are smaller and gentler, but fighting all the same to maintain their products of quality and the role of the small farmer and producer in an ever more global economy.

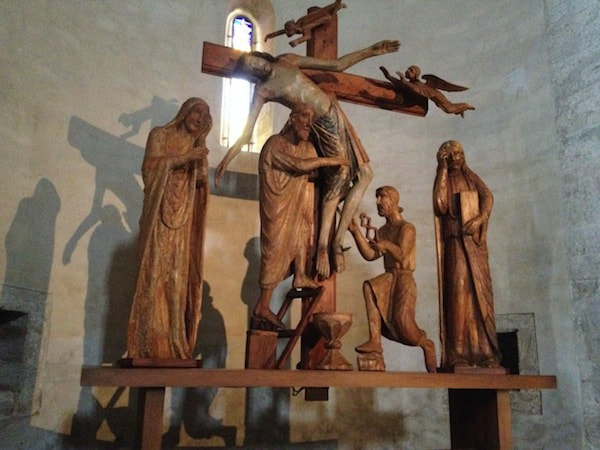

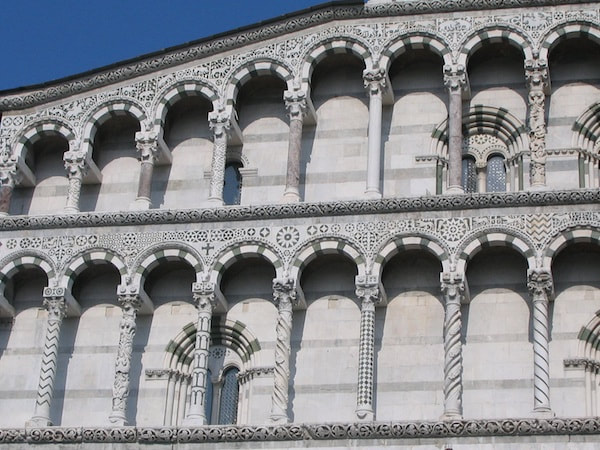

Find out more about the Giants of Sardinia tour here. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 26 August, 2018. I’m often asked whether my food and wine tours also include cultural sites and activities. They do. Resembling Rudyard Kipling’s elephant child with a ‘satiable curtiosity’, although I haven’t met my crocodile — yet, I ask ever so many questions and include everything and anything that turns out to be interesting. One tour is based around traditional spinning, dyeing and weaving. Sometimes there’s a concert with music by Puccini, a native son of Lucca. Since I’m posting this on Easter Sunday from a Catholic country, I’ll tell you about some of the churches in Lucca and the Garfagnana that I take my guests to see. My all-time favourite is the duomo (cathedral) at Barga on the edge of the Garfagnana. Parts of it date back to 1000 AD. Inside the hush is palpable. The wordless stones breathe tranquility and peace, and golden light seeps through the alabaster windows. A magnificent marble pulpit stands alongside naive romanesque heads and inlaid figures. A 3.5 m (11.5 ft) tall mediaeval carved wooden St Christopher with an undersized baby Jesus on his shoulder keeps guard over the whole church from his place in the apse. From the piazza in front of the church, you look over Barga and the Serchio River valley to the craggy Alpi Apuane opposite. Even though I’m not religious, I often go sit in this peaceful haven. Lucca has been called the ‘city of a hundred churches’. The Basilica of San Frediano stands out for its mosaic façade, the only one in Lucca. But what draws me there is one painting, one wooden statue and especially Santa Zita. Zita, a serving girl in a noble household, was a favourite of the family. However, she had a secret. Every evening she sneaked into the kitchen, wrapped the leftover bread in her apron and took it away to give to the poor. The other servants, being jealous, told their master she was stealing. He could hardly believe it. He waited for her one evening and challenged her to open her apron. She was very frightened but did as she was commanded and, by a miracle, in place of the bread, her apron was full of flowers. Her somewhat gruesome mummy, lying in a glass coffin in a side chapel, is redeemed by her blue servant’s dress, crisp white apron and the legend of her charity. If there isn’t a good story, I make one up. I’ve invented one about San Michele, in the Roman Forum of Lucca, and the duomo, San Martino. Ranks of decorated columns are stacked up their façades. I like to imagine an annual column competition with the winner getting his (I expect there weren’t any female sculptors then) column added to the row. Maybe the runners up also got theirs up there, or else it would have taken an exceedingly long time to collect so many pillars. Of course I admit this as my own fantasy. Perhaps this church in Villa Basilica, outside Lucca, with far fewer columns was the trial run for the column competition? There are so many exquisite romanesque churches in the countryside I’m tempted to design a walking tour visiting them along with food and wine producers and restaurants on the route.

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 8 April, 2012. By Alison Goldberger When I wanted to learn how to make salami I knew travelling to Italy was the only way to do it, so I booked onto the Advanced Salumi Course in Tuscany with Sapori & Saperi Adventures. The course was incredible, and I learned so much. I was also so impressed by Erica and her company that I asked her if we could collaborate. I’m a Scottish journalist and organic pig farmer but have lived and worked in Austria since 2015. Now I assist Erica with social media and online marketing. I absolutely love telling people about my time on her course and now I am excited to share with you why I think travelling with a local expert in 2022 (and beyond) can only enhance your holiday experience! Eat in incredible restaurants...and in private homes One of the most wonderful experiences I had was to dine in restaurants uncovered by Erica after years of eating and living in Tuscany. You can be guaranteed you’re not just eating in the restaurant all the other tourists found online! We were treated to dinner at Il Vecchio Mulino, where Andrea brought out course after course of exquisite local food. Many of Erica’s courses and tours also include meals in private homes. In Capezzano I was welcomed into Gabriella’s home where I ate the best seafood I’ve ever had. The freshest seafood cooked to perfection and an extremely warm welcome – it was an unforgettable experience. Learn how to make prosciutto as the artisans do Do you have a passion for prosciutto like I do? It’s unlikely you can just stroll up to any producer and they’ll tell you how it’s done. But when you travel with a local you certainly can, and they are happy to answer all your questions. When learning all about salumi in Tuscany I visited numerous artisans and gleaned the knowledge they’ve garnered over a lifetime. On these tours you’re also supporting these very small businesses, creating wonderful slow food with a passion you’re unlikely to find in large-scale producers. What’s more, you get to taste their incredible products! Savour products from small-scale producers You want to visit a local organic olive oil producer, or have always wondered how chestnut flour is produced, or perhaps gelato is more your thing? These were all requests during my course and every one was fulfilled! I took home a bag of chestnut flour after seeing how chestnuts are dried and milled. I sampled the best pistachio gelato at Cremeria Opera in Lucca and bought the tastiest new-season olive oil from Claudio Orsi of Alle Camelie. Erica has built up so many contacts across the region and she is happy to help visitors find what they’re looking for.

Erica drove us during our course so she was always on hand to answer questions and give us explanations about what we were seeing as we travelled. It was information born from a passion for Tuscany and gave us a wonderful insight into the history of the region as well as what it’s really like to live there. This is a feature of all tours and courses from Sapori & Saperi. For instance, on the Tastes & Textiles tours participants learn all about Lucca’s rich tradition of producing textiles. Meeting local craftspeople provides a wealth of knowledge you couldn’t get elsewhere! Did someone mention gelato I know one of my first thoughts when I think of Italy is gelato. We were taken for a quick pit-stop to sample some delicious gelato. It was actually in the Cremeria used for the Art & Science of Gelato course run by Sapori & Saperi. During that course participants immerse themselves in the icy world of Mirko Tognetti of Cremeria Opera Naturali per Gusto, Lucca. They learn his secrets and the science behind gelato and how to create their own flavours. Sounds like an absolute dream to me!

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 20 January, 2019. Italians exploit every opportunity to celebrate as a community and right now it’s Carnival, time to have fun before the penitential period of Lent. The Carnival at Viareggio is strong competition for the one at Venice, and it’s so little known outside Italy that you rarely hear a foreign language being spoken. Everything is focused on the festive parade of magnificent papier mâché floats that sally forth every Sunday for a month or so and on Shrove Tuesday (the schedule changes each year). You need to arrive early to get a parking space, but you won’t get bored while waiting. The setting is the passegiata or boardwalk with its backdrop of ‘stile liberty’ buildings and beach establishments. People of all ages come to enjoy the spectacle, many showing off their costumes. Animals are there too. If you’re alert, you’ll see some amusing vignettes. There’s fast food… …and slow food. At 3 pm three canon shots announce the start of the parade of floats. Some are several storeys tall… …and others are people on the ground wearing elaborate headdresses. Some satirise politicians… …and some feature films and pop stars. Some are monuments to the skill and ingenuity of the people who design and build the floats, now full-time jobs. As the sun sets, the floats go round for the last time and spectators drift happily homewards. I’d like to thank Klaus Falbe-Hansen for his keen eye, excellent photos and unfailing sense of humour at Carnival 2010.

You still have time to catch one of the Carnival parades at Viareggio this year (2022): Sunday 20 February - 3 pm Fat Thursday 24 February - 6 pm Sunday 27 February - 3 pm Fat Tuesday 1 March - 3 pm Saturday 5 March - 5 pm Saturday 12 March - 5 pm If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 12 February 2012. The etymology of the Italian word antipasto is ‘anti’ meaning before and ‘pasto’ meaning meal. My Italian-Italian dictionary adds that they are served before the beginning of the true and proper meal. So, how much can you eat right before you eat a ‘true and proper’ Italian meal? Remember that it consists of two courses, the primo or first course and the secondo or second course. The second course may have side dishes, contorni, and is often followed by the dolce, or sweet course. The Italians I know have differing opinions about the correct number of antipasti (plural of antipasto) to be served at a ‘true and proper’ meal. Stefano of Cantina Bravi in the Garfagnana can’t bear to serve fewer than seven. Nor can Agriturismo L’Orto in Sardinia (if you count the olives). Despite my begging her to reduce the number, Gabriella ignores me and continues to produce five at the seafood dinners she prepares for my salumi courses in Tuscany. Which would you choose? Returning to the dictionary, it says the antipasti are supposed to whet the appetite. Personally, I find more than one puts a damper on my appetite for the rest of the meal, and finally I’ve found some Italians who agree with me. I invited Marzia (one of my cheesemakers) and her husband to dinner last night. Since I figured one antipasto would never satisfy an Italian, I decided to serve three. A bit meagre, I knew. By the time we got to the secondo, a stuffed roast guinea fowl, they said they were already full. They declared that antipasti kill their appetites, and they could easily do without any. I must remind them next time my cheese course is at their house for dinner and they serve seven antipasti!

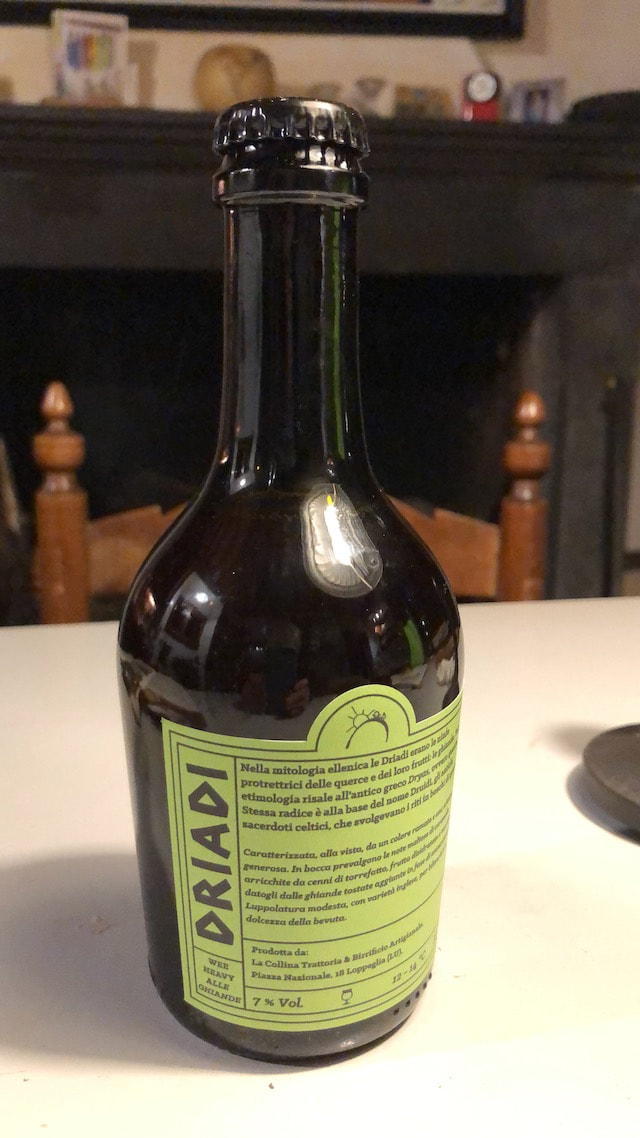

Back to my question: how many can you eat? If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 31 March, 2019. I admit we weren’t dancing on the tables. It wasn’t that wild, but there was some heady acorn beer. And there’s the clue. Every dish was enriched with wild plants foraged by Stefano Pucci, the environmental guide whose walks I often go on. After a week of over-indulgence, practically a legal requirement for Christmas and New Year festivities in Italy, I look back with pleasure on that convivial meat-free meal I had in October at the trattoria and micro-brewery La Collina at Loppeglia (Pescaglia). Stefano has been foraging for wild plants since he was a boy. He’s never happier than when in his beloved woods on the slopes of the Alpi Apuane mountains, and nothing is too much trouble or too time-consuming for him. The acorns, for example. He collects them, cleans them and mills them by hand with patience and care. I daren’t ask how many hours of labour this entails, especially since he collects enough for Alessandro, the master brewer at La Collina, to make a batch of excellent acorn-flavoured beer named Driadi. Whoa! Aren’t acorns poisonous? I remember learning when studying anthropology at Berkeley that California Coast native Americans had figured out how to remove the toxins. Maybe I’m misremembering; it was a long time ago. Stefano reassures me that they’re not dangerous, and I’m still here to tell the tale. In the kitchen Paola worked her magic on Stefano’s foraged plants and interesting varieties of more common plants from his vegetable garden. The Annotated Menu Dish by Dish Nido di polenta al pesto Ombelico di Venere Nest of polenta with pesto of Venus’s navel It’s called navelwort in English without specifying whose navel, and Umbilicus rupestris in Latin. It’s a fleshy plant in the stonewort family (Crassulaceae). Stefano adds that it was an important food of mediaeval pilgrims. ‘Wort’ was used in English names of plants and herbs used for food or medicinally. Perhaps coincidentally but then again maybe not, wort is also the sweet infusion of ground malt or other grain (not to mention acorns) before fermentation, used to produce beer and distilled malt liquors. Who would have guessed this is what Venus’s navel looked like? I checked out Botticelli’s painting ‘Venus and Mars’ (‘Venere e Marte’), but she’s fully clothed. Crostone con pomodoro fresco al Satiro Large toast with fresh tomato and Satyr’s herb In Greek and Roman mythology satyrs were lustful, drunken woodland gods. Drinking acorn beer, no doubt. From the libidinous to the botanist (not to imply that a botanist can’t be debauched), the scientific name is Satureja montana. In English we call it winter savory, which might sound less lascivious, but savoury can mean spicy and piquant. Maccheroncini ai porcini della selva pescaglina Maccheroni with porcini mushrooms from the Pescaglia woods Maccheroni in this part of Italy isn’t elbow macaroni. It’s thin squares or rectangles of egg pasta, usually made by hand, as it was in this case. Casarecce all'aglione Casarecce with giant garlic Casarecce are a type of short, dry pasta. Stefano explained that aglione dates from Etruscan times and comes from the Val di Chiana, southern Tuscany. He grows it in his vegetable garden. It doesn’t contain alliin, the chemical which, when exposed to air, is metabolised to allicin which gives normal garlic its strong, characteristic smell and flavour. Finally I understand the dish you often see on menus around Siena, pici all’aglione. Pici are thick strands of spaghetti, and the sauce is a simple tomato sauce with lots of aglione. No wonder when I tried to make it at home, the garlic was always overpowering. In my ignorance, I used normal garlic instead of aglione. I wish someone had told me long ago. Frittata con Silene Alba con patate rosse dell' orto di Ubaldo al forno Frittata with white campion and roast red potatoes from Ubaldo’s orto You probably know that a frittata is beaten egg cooked in a frying pan and, if you’re adventurous, flipped over when the bottom is cooked. Don’t tell anyone, but I put mine under the grill to finish the cooking, so as to avoid ending up with the frittata on the floor instead of in the pan. You can add almost any cooked vegetable to the egg before cooking it. Here it’s Silene alba or white campion, a wild herb with a slightly sweetish flavour. The red potatoes came from Stefano’s garden, named Ubaldo after his father, and were grown without any irrigation. Ghianducci e Vin Santo This is a play on the word cantucci, the typical Tuscan biscuit or cookie containing almonds and often called biscotti in English. Instead of using wheat flour, these were made with acorn, ghiande in Italian, flour milled by Stefano. Vin santo (sacred wine) is a Tuscan dessert wine in which you dunk your ghianducci. All this for only €23! If you live near Lucca and speak Italian, I highly recommend Stefano’s walks. You’ll always learn something new and interesting. You can find them at Stefano's website and Facebook page. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here http://eepurl.com/geSMLv

If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here http://eepurl.com/hVwz6 What does Tuscan heritage mean to you? Do you think of Florence and its famous art and architecture? The leaning tower of Pisa? Maybe the landscape of vineyards, olive groves and pencil cypresses that give us Chianti and olive oil? My Italian friends from Lucca helped me design a tour based on their idea of their own heritage. They envisaged a tour that snaked diagonally across the region from Sansepolcro and Arezzo in the southeast to Lucca in the northwest. Chianti yes, but not the vineyards that leap to mind. Art and architecture yes. But no Florence. No Siena. No Pisa. Here are ten experiences they don’t want slow travellers to miss. 1: Sansepolcro (Arezzo Province) Why there? For two reasons. 1 The fresco of the ‘Resurrection’ by the hugely influential early Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca. You don’t have to be religious to be spellbound by it. Aldous Huxley called it the ‘greatest picture in the world’. 2 The Tuscan cigar. I don’t smoke and I think it would be better if no one did. But it turns out that tobacco was undoubtedly a major player in the history of Tuscany ever since 1574 when it arrived in the very spot we’re staying: Sansepolcro. From smuggling to women’s work you’ll hear all the pros and cons of tobacco at Roberta’s tobacco farm. Whatever your views, it’s fascinating seeing how tobacco leaves are harvested by hand and smoke-dried. 2: Anghiari (Arezzo Province) An English friend who accompanied me on a research trip said that of everywhere we went, it’s the place she most wants to return to. Its striking position poised on a cliff edge is attraction enough. Add to that a tour of the Jacquard looms at the Busatti linen mill, and you’ll want to return too. 3: Chianti (Florence Province) Could Chianti wine be even better if they restored all the dry-stone walling that was demolished when tractors blazed a trail through the vineyards in the 1960s and ‘70s? You can judge for yourself during a vineyard tour and tasting. 4: White Truffle (Pisa Province) San Miniato claims their white truffles are better than the more famous ones from Alba in the Piedmont. Follow the Lagotto dog, find your truffles and relish lunch with truffles in every course (except dessert). 5: Vicopisano (Pisa Province) When the Florentine Republic conquered the Pisans in 1406 they commissioned their star architect-engineer, Filippo Brunelleschi—famed for the dome of the duomo of Florence—to redesign the Pisan fortress at Vicopisano. My historian friend from Pisa says you mustn’t miss this magnificent castle, and he’s going to show you around himself. 6: Extra virgin olive oil My Slow Food friends are sure you have no idea how good extra virgin olive oil can be until you taste it here in Tuscany. It deserves the same attention you lavish on wine. 7: Lucca (Lucca Province) Lucca is so conservative that it never tore down its Renaissance walls, as if waiting for another attack. It may as well be us. And who better to show us around than a descendant of one of the noble families who ruled Lucca in the Renaissance! 8: Puccini (Lucca Province) Baritone Mattia Campetti insists that every visitor to Lucca must hear the music of that great operatic composer Giacomo Puccini in his home town. Mattia will give you a vivid and amusing tour of Puccini’s home at Torre del Lago. Be prepared for an entertaining concert when Mattia is joined by his soprano wife Michelle Buscemi. 9: Tuscan grill On the grill are a pig and a cow (no apologies for sneaking in two items here): the indigenous Cinta Senese pig (belted pig of Siena) and the white Chianina cow, possibly a descendant of the huge Palaeolithic aurochs. Their succulent flavour hasn’t diminished at all over the millennia. 10: Cantuccio (biscotti in English) Every Tuscan meal must end sweetly with cantuccini dunked in vin santo, our Tuscan dessert wine. How to book the Tuscan's Tuscany:

If my Tuscan friends have convinced you to come see Tuscany through their eyes, have a look at all the tour details here (click on the tabs below the introduction and read what appears in the window below) and email me for a booking form. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here.

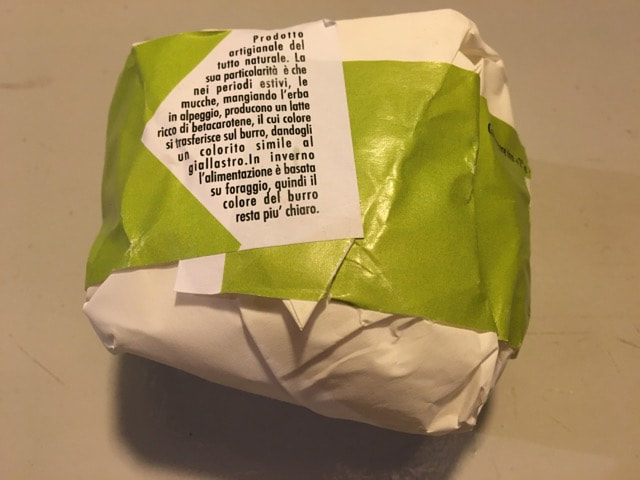

Butter isn’t an ingredient you’ll find in traditional Tuscan cuisine. The people north of the Apennine Mountains have cows, and they make butter. In Tuscany we have sheep. Their milk is used to produce pecorino cheese (the word for sheep is ‘pecora’ and the cheese made from their milk is ‘pecorino’).

In the Garfagnana we have a native all-purpose cow good for a bit of both milk and meat, which since the diffusion of modern specialised breeds and until very recently was considered good for nothing and nearly died out completely.

Families made a little butter which they used primarily in sweet dishes. In a local cookbook compiled by a woman of Lucca, out of 179 savoury recipes only four call for butter, three contain béchamel sauce and one is the recipe of a chef who had emigrated to New York. On the other hand, almost every single one contains extra-virgin olive oil. Out of 33 desserts, 23 use butter, mostly in the pasta frolla crust of pies.

Occasionally you come across a cow family, like the Nesti of Melo (Cutigliano) into which Daniela Pagliai married. (Women rarely take their husband’s surnames, although the children bear their father’s name.) Daniela had been her father’s shepherd since she was nine and in charge of making pecorino from the age of 14. When she married, she had to change gears. She now makes several types of cow’s milk cheese, yoghurt, gelato and butter. For more about Daniela, see my blog post: Like the Seasons: the Life of a Cheesemaker.

When I take my guests to her, I always buy some butter. It conforms to two of my rules when buying food: very few ingredients and nothing I can’t understand. Andrew Wilder of Unprocessed October calls it the Kitchen Test. Daniela’s butter contains one ingredient: panna, cream.

When I first started visiting her, butter was such a minor product that she didn’t even have a special label for it. She sold it in a ricotta wrapper. Now there’s not only a label, but also an informative essay.

Daniela says: ‘Completely natural artisan production. Its distinctiveness is that during the summer the cows graze in alpine pastures producing milk rich in betacarotene, whose colour transfers to the butter making it yellow. In winter, the feed is based on hay [not silage] and the butter is paler.’

They say that variety is the spice of life, and it’s often these tiny details that distinguish the truly artisan product from a standardised industrial one. Of course, nothing beats visiting the producer and checking their claims for yourself. If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 25 September, 2016. If you come to Lucca for only a day, arriving from Florence late morning and off early the next to get to the Cinque Terre, you’ll miss the pleasures of Borgo Giannotti. Compared to the amphitheatre, the Guinigi Tower with oaks growing on top, the wedding-cake columns of San Michele church and the massive encircling walls of the historic centre, Borgo Giannotti doesn’t look like much. Immediately outside the north gate of Lucca, it was a meeting point for merchants coming from the port of Viareggio, a place to stop and refresh themselves before turning up the Serchio Valley to sell their merchandise in the Garfagnana. It developed into a thriving artisan quarter, and retains that vibrancy of people making and doing things, occupations that the waves of mobile phone shops haven’t yet totally swept away. So come with me for a Saturday morning trawl in Borgo Giannotti. We might be mistaken for drunks, rare as they are here in Lucca, weaving from one side of the street to the other following the trail of my favourite places. On the left we come to coffee importers and roasters Bei & Nannini. It’s not my favourite coffee, but I like the shop front and, apart from the coffee beans themselves, it’s local. It was founded in 1923 by Guido Nannini and Giovanni Bei and is still in the ownership of the two families. There are many small groceries, delicatessens and specialist food shops in Borgo Giannotti. You can do all your shopping from the friendly vendors in the space of a few hundred metres without ever entering the anonymity of a supermarket. Crossing over to the right we find a fishmonger. Over on the left is one of many fruit and vegetable shops. Since it’s Saturday, we’ll continue up the street to the farmers’ market. Still on the left, look at that exquisite tiled shop front (it was even more beautiful before some developer painted over the ochre wash above). On the right we come to a bakery with many enticing goodies in its window. I suspect torta di erbi is a relict of Renaissance, and maybe mediaeval, times when sweet and savoury were often mixed in a single dish. As strange as it sounds, this delicious tart is filled with Swiss chard, parsley, bread crumbs, raisins, candied peel, pine nuts, grated pecorino and parmigiano, sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, rum and eggs. Becchi means ‘birds’ beaks’ and refers to the form of the pastry; shaping them is a skill in itself. Over on the left again is a tap where locals come to fill their water bottles for drinking at home. It’s free! Next to the fountain is Angolo Bazaar where you can find almost any utensil or container you need for your household and many gifts to take to friends at home. It used to be on the corner (angolo), but moved down one space to make way for a discount sport shoe shop. Via Stalle means street of the barns—something like a mews in London. You could spend a couple of hours in this Aladdin’s cave starting with the baskets at the front and penetrating into deeper and deeper caverns stacked from floor to warehouse ceiling with crockery, wooden kitchen utensils, garden tools, hosepipes, canvas—an inventory too long to list. I’ve brought my sickle and pennato lucchese (a kind of billhook) to be sharpened opposite at L’Arrotino. Many people take their utensils to artisan sharpeners, and itinerant ones come to some open-air markets. The Bertinis have been sharpening knives in Borgo Giannotti since 1956. They also sell quality knives from those forged traditionally in Italy to Japanese knives of Damascus steel. Every kitchen needs at least one! Continuing on the right, we come to a delicious smelling grocery stuffed with tasty products, including tortellini fresh from the Favilla pastificio of Lucca. There’s something special along the road to the right, but first we’ll continue to the top of Borgo Giannotti. When it’s lunch time, we can eat at Buatino, where the cook changes the menu every day to take advantage of seasonal ingredients. We cross over the outer ring road and come to the Foro Boario. This has nothing to do with wild boar. Boario refers to cattle and the Foro Boario was the cattle market, used in September when herders brought their animals to sell in the city. The Festa della Carne e della Macelleria Tradizionale (Festival of Meat and Traditional Butcher Shops) held annually in the middle of September commemorates this practice. More in the old spirit of farmers selling their produce to the public is the farmers’ market that takes place at the Foro every Saturday morning. If you buy your fruit and vegetables here, they’ll be fresh and seasonal. You’ll meet the growers and can ask for recipes for ingredients you’ve never used before. Time for a coffee at the bar opposite the Foro and then we walk back to the monument, which turns out to be a road sign. We turn left and if I weren’t with you, you’d walk right past this grey-green building and boring gate. You would be missing a great treat. It’s a handmade tile factory founded by the current owner’s great-grandfather in 1902 to make tiles in the ‘Liberty’ or Art Nouveau style, which was all the rage in Europe at the time. Press your nose against the dirty showroom window (perhaps never washed since 1902?) and you can see some of the patterns that Francesco Tessieri’s four artisans still make by the same techniques. They’re closed on Saturdays, but if we come on a weekday, Francesco will take us into the workshop and explain as we watch the process. Among his many commissions were restorations of floors in the homes of Gucci and Pavarotti. Around the corner are some over-the-top examples of ‘stile Liberty’ houses whose floors are surely paved with Tessieri tiles. Our tour is done and it’s time for a delicious lengthy lunch accompanied by good wine and conversation. So like the merchants of old, why don’t you make Lucca your city to dawdle in, to catch your breath and refresh yourself?

If you landed here by chance and would like to be notified of future posts, you can sign up here. If you’d like periodic news about our tours and courses, sign up here. This blog was originally published on Slow Travel Tours on 13 January, 2013. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed