|

The cheese course group arrived 45 minutes late at Daniela’s dairy. She had already added the rennet, the enzyme that speeds up coagulation of the curd, to have the curd ready for our planned arrival time. Now it was past its best. We feared we’d ruined her day’s production of cheese. Daniela’s youthful appearance belies years of experience making cheese. She knew the curd couldn’t be used to make a hard cheese to be matured for several months, so we used it to make some soft cheeses: stracchino and raviggiolo. I first went to visit Daniela Pagliai at her organic farm I Taufi early last June. I had learned about it from the address on the wrapping of some exceptional butter I’d come across at a gastronomia in Ponte a Moriano near Lucca. The wrapping claimed the contents were ricotta, so I assumed Daniela also made cheese, and I warmed to a person who wasn’t uptight about precision labelling. (Not that ricotta is cheese, but you have to make cheese first and then use the whey to make ricotta.) The address of the farm was Melo. I didn’t know Melo, but I’d been to the picture postcard town of Cutigliano from which you ascend the Pistoiese slopes of the Apennines, it seems like forever, to get to Melo. What appears on the map to be at the edge of civilisation, turned out to be a hub of pastoral activities with Daniela at the centre. On this first meeting she appeared self-possessed, only mildly curious about my tours and calmly accepting of my request to bring clients to watch her make cheese, as if life often brought novelties to her door. A warm honesty flowed from her candid smile and guileless eyes. She showed me her modern dairy, the maturing room and the cows in the barn. Her younger daughter clung to her apron; the older one arrived home from school. I was much more curious about her than she about me. In the dairy she had fondled a spino, the wooden stick traditionally used to cut curds, so I knew she respected tradition. I asked diffidently whether the cows ever went outside, and was relieved to hear they still practise transhumance, taking the cows to alpine pastures a couple of hours’ walk above where we were now. The cows have to wait until school is out and the whole family can up stakes and move to their summer home. We went to see it without them. On a shelf I noticed a slim book entitled Come le Stagioni: Daniela Pagliai (Like the Seasons), a biography of her written by a friend from Pistoia in the form of an interview. I bought a copy and learned she was practically born making cheese. During school holidays she and her dog herded her father’s sheep. By the time she was 14 she was in charge of the pigs and all the phases of cheesemaking on the family farm. At 16 she married Valter and discovered that his contribution to the marital economy was a herd of milk cows. She moved to her in-law’s farm and transferred her cheesemaking skills to cow’s milk. After five years she and Valter realised their dream of buying their own farm and becoming organic. In the book she sums up her philosophy of life: ‘I think there are many types of “love” all led by the heart. Without its beating, there can be no beginning. I’m not talking only of the beating that pumps blood through our veins, but also the beating for our children, our parents, our house, our land, our work, which are all united in one thing: love. ‘How can I explain to you how much I love my life and my work? How can I make you understand what I feel for my children and my husband? For nothing else in the world and no other life in the world would I change my own life and these loves. ‘For me life is like the seasons: moments of joy are like the flowers and perfumes of spring and like the ripening of its fruit and the embrace of the hot summer sun. Moments of melancholy are like the autumn with its rain, which sometimes also streams from my eyes, and like the winter, because you have to move with the rhythm of the snow, delicately placing your feet like the large snowflakes descending joyously from the sky, sprinkling the roof and our valley, and walking, walking lightly, toward a new spring.’ There was still snow on the ground when I took Giancarlo Russo to visit Daniela in preparation for our new cheese course. He approved, and Daniela became part of the course in which Giancarlo teaches the theoretical sessions. For more information about the Theory and Practice of Italian Cheese course: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/courses_with_artisan/theory-practice-of-italian-cheese/

My thanks to Kirby Piazza for his photographs of Daniela and the farm.

0 Comments

This week I got into a Fiat Panda 4×4 that turned out to be a time machine. The precise date to which it took me was 1969, but it could easily have been a couple of centuries earlier. Renato, the butcher and shopkeeper of my village Casabasciana, wanted to take me somewhere hidden. He knows I like walking in the wilderness, and thought this place would appeal to me, but wouldn’t reveal any more. We fixed Thursday afternoon, and I gathered my equally curious and appreciative friends Lone, Klaus and Tove to accompany us. Crammed into the Panda, we drove down the hill to the Lima Valley and turned right toward Abetone and Renato’s home town of Popiglio. Opposite the road to Lucchio, before Popiglio, we turned left into a gravel lane where Renato’s cousin Giuliano was waiting for us with his Panda 4×4. We divided ourselves between the two cars and bounced and wound up the eroded track, passing an occasional farm building. Just when it seemed we couldn’t go any higher, we reached the end of the road and the farmstead where Renato’s and Giuliano’s mothers and Giuliano himself were born. The sky was a uniform grey that day which added to the mood of desolation. The buildings sat on a narrow terrace, with stalls and pigsty beneath the house on the downhill side and the main door at the back. Numbers 1 and 2 must have been the buildings we passed on the way up. Giuliano opens the main door and to our right is the kitchen, focal point of a farmhouse. There are almost too many things to take in, objects signifying a different way of living. The family tries to keep the place in good repair, but it’s becoming more and more difficult. I’ve seen these burners in many old houses. You put coals from the hearth in the iron boxes and a trivet on top on which to rest the pot. The bottoms of the boxes are gratings that allow the ash to drop through and you remove it through the square holes beneath. The bedrooms are on the upper floor. Renato explains that this object was made from thin strips of chestnut wood. You hung a pot of hot coals on the hook inside at the apex and placed it under the covers as a bed warmer. We all giggle at the idea of a priest in the bed. In the background another model of ‘priest’, and in the foreground a tool to hold a skein of yarn while you wound it into a ball. The upstairs landing, like the kitchen, was another ethnographic museum. Giuliano’s father and grandfather were charcoal burners. There was a mountain cable car for hauling heavy goods up to the house. The tour of the main house concluded, we went to see the rest of the buildings. At the far end of the courtyard the door on the right opened into the much smaller house where Renato’s mother was born. Renato asked if we could guess why they left the courtyard covered with weeds. Because the pavement was so beautiful that if anyone saw it, they’d be up there with crow bars in an instant. The metato was the building in which chestnuts were put (‘mettere’ means ‘to put’) to dry on a slatted ceiling above a smouldering fire before being shelled, sorted and taken to the miller to be ground into flour. Back in the house we had seen some of the other tools required for the later stages. When the earthquake of 1920 caused landslides that covered several villages, the lower walls of houses were reinforced with these stone buttresses, just like a mediaeval fort, one of which we could just see across the Lima valley. Above the tiny village clinging onto the wooded slope are the remains of a fortress, part of Lucca’s late mediaeval line of defence against the Florentines. There was an almost unwelcome surprise. Adjoining the far end of the house was another house, owned by other people from Popiglio. They had brought it right up to date, including a television aerial. I wanted to see where the charcoal pile used to be. We drove back down the road a few hundred metres where we were greeted by more spectacular views. We know Vico Pancellorum well because of its restaurant Buca di Baldabò, one of our favourites in the area. On the spot where the charcoal used to be produced was a strange orchid. It has no chlorophyll, but is a saprophyte which feeds on rotting vegetation with the help of a symbiotic fungus.

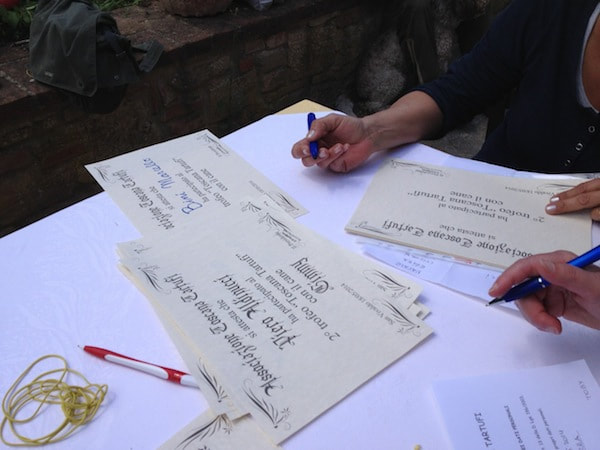

As we drove away, we learned the sad subtext to the visit. The family had concluded they had to sell the house. Their children have no interest in it, and since Prime Minister Monti introduced more taxes for uninhabited buildings, it was becoming too much of a financial drain. Their 7 hectares (14 acres) of fields and woodland are also subject to taxes. The top half of the road is private and requires constant maintenance. But who would buy it? Do I know anyone? I’m just back from the second annual Tuscan truffle hound competition organised by Riccardo, my truffle hunter. The competition is about as exciting as a village cricket match without the beer tent. Very little happens, but it does have the merit of being easy to understand the rules, unlike cricket (at least for me). I used to listen occasionally to a cricket match on the radio enjoying the foreign language of the commentators. Truffle hunters also have their own language which seems to consist of one- or two-syllable utterances to which the dogs rarely listen. This video gives you some idea of the pace and mutterings. [vimeo]https://vimeo.com/95670529[/vimeo] If it’s not much of a spectator sport, at least it demonstrates the method used and patience needed to train a dog to be a good truffle hound. There are very few breeds that can’t excel, but you have to start the training when they’re just a few weeks old. Give them simple commands, teach them to retrieve a stick and eventually bury a plastic capsule with a fragment of truffle in it for the puppy to find—over and over and over again. Riccardo explains the psychology of training: dogs are pack animals and the man (I haven’t met a female truffle hunter yet) has to play the role of leader of the pack. Some men don’t have it in them. Others have figured out how to motivate their dogs to keep their noses to the ground. Riccardo and Teo demonstrate best form. Note his subtle hand movements. While not exactly electrifying, the location is beautiful and the camaraderie enjoyable. What better way to spend a sunny Sunday than chatting to friends while sitting on a stone wall in the shade of a pergola at San Vivaldo monastery. When the trials are finished, all the dogs and owners converge on the ring to retrieve the buried capsules. At this point a Franciscan friar emerges and surveys the scene. He gazes at the small square marked out on the lawn, shakes his head and states that surely in so small a space every dog would find every truffle. Meanwhile, the certificates are being prepared and the prize-giving begins. In 15th place, the man whose dog found none. No one’s a loser. In first place, a man no one knows. He wants to be notified of the next contest, but doesn’t understand what an email address is. What sets a Tuscan truffle hound competition apart from a cricket match is lunch. We drift into Il Focolare (‘the hearth’), a restaurant in the cellars of one wing of the monastery, for an abundant and well-cooked lunch. Riccardo and I have taken many guests on real truffle hunts (no plastic capsules) followed by a truffle lunch at Riccardo’s home (click November, but you can hunt truffles in almost any month). We’ve also designed an intensive truffle course, and soon we’ll have a truffle weekend on offer as well. Let me know if you’d like to be notified when it’s ready: info@sapori-e-saperi.com.

Pasqua is Italian for Easter. Last year I went to Francesca Bonagurelli’s agriturismo Al Benefizio to join her family and friends for their typical Easter lunch. Queen of the day Francesca at the right edge of the photo nearest the kitchen, her daughter, her nephew, her cousin from Milan, her brother-in-law, her sister, her mother and her dear friend Marta. An antipasto consisting of the usual crostini and some olives didn’t prepare me for the surprises to come. The primo was something I’d never had before: gnocchi alla romana. Instead of the little potato cylinders, these circular cakes were made of semolino polenta to which egg yolks and parmigiano was added. And instead of boiling them, they were sprinkled with butter and more parmigiano and browned in the oven. Delicious! The secondo, roast beef, was accompanied by enough vegetables to please any of my clients, who are always asking, ‘Where are the vegetables?’ Here again there was a surprise: a vegetable looking like the hair of a punk angel who had dyed it bright green. It was Salsola soda, a saltwort that grows around Mediterranean coasts and is harvested between March and May. In Italian it’s called agretti or barba dei frati(monk’s beard—a punk monk?). Wikipedia tells me that it was important historically as a source of soda ash, one of the alkalis needed for soap and glass making. The clarity of cristalloglass from Murano depended upon soda ash. As a food it’s supposed to have a detoxifying effect. Just when we thought we would burst, the table was cleared, the cakes arrived and the spumante was uncorked. Naturally there was a colomba di Pasqua (Easter dove), a traditional Easter cake similar to panettone served at Christmas. Recently arrived from Naples was another novelty: the pastiera napoletana wrapped in its Easter finery. One legend reveals its origin. One night some fishermen’s wives left baskets of ricotta, candied fruit, wheat, eggs and orange flowers on the beach as an offering to the sea, so it would protect their husbands and bring them back safe and sound. The next morning, when they descended to the beach to greet their returning husbands, they discovered that the waves had mixed the ingredients, and in the baskets was a cake.

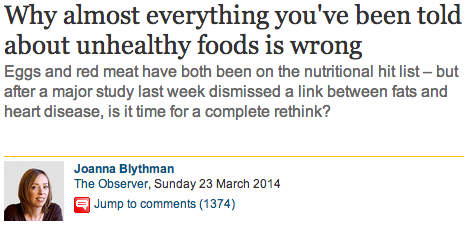

I feel vaguely uncomfortable every time I hear the phrases ‘healthy eating’ and ‘balanced diet’. It’s not that I disapprove of eating healthily or balancing my diet, it’s just that I’m not sure we can ever know what these terms mean. A recent article in The Guardian newspaper by Joanna Blythman highlighted the problem. Click here to read the whole article. It’s worth browsing a sample of the 1,374 comments too. What tempted me to add my voice to the throng is that I think there’s something much more fundamental wrong with what we’re told. I once took part in a UK medical research project aimed at discovering links between diet and women’s health. Every so often they asked me to fill in an online form giving details about what I’d eaten the day before. The designers of the project and the form clearly didn’t have me in mind. For example, in the section asking how many slices of bread I ate, they asked whether it was white or wholemeal, but there was nowhere to say I’d baked it myself using stoneground, organic wholewheat flour I’d bought from the miller. Nor to state it didn’t contain any flour improvers and was made by a long-rise sourdough method. Although I believe it’s healthier than mass-produced bread, do I know for sure? No, and this study wasn’t going to reveal the answer. Another major problem with all dietary research based on surveys is that people lie. Do you want the researchers, or even yourself, to know that you ate three Kit Kats and drank a whole bottle of wine yesterday? And what about the problem of the long-term effects of particular substances? In the laboratory biologists can test the effect on animals of chemicals occurring in food, either naturally or as additives during cultivation or processing. But as far as I know it’s difficult, maybe impossible, to test the effect of ingesting that substance for 20 or 50 years.

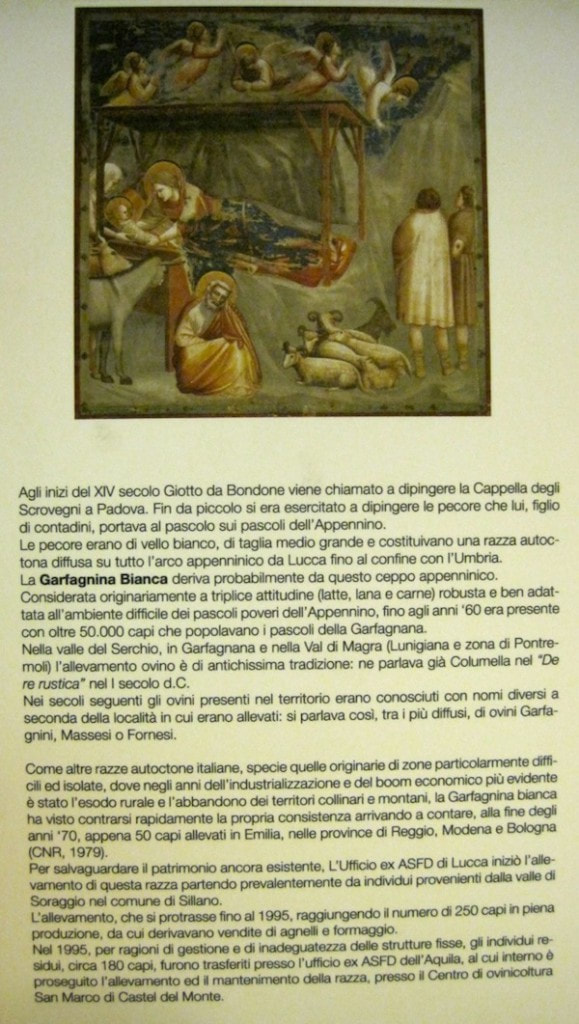

The last of my doubts about dietary advice stems from genetics. We’re all different. One person might live to 100 eating nothing but red meat and fat, whereas another dies of a heart attack at the age of 52. Was it their diet or their DNA? Many years ago when asked on her 120th birthday to what she attributed her longevity, the oldest woman in France replied it was giving up smoking when she was 118. On my tours you eat unprocessed food, much of it straight from the artisan producer. In my opinion it tastes much better than industrial food, but I can’t claim it makes you healthy. Next chance to taste for yourself is the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June (http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/component/content/article/2-small-group-tours/56-cheese-bread-a-honey). At noon on Wednesday 9 April in Florence, Dr Francesca Camilli of the Italian National Research Council will present a paper to the 1st European UNESCO-SCBD* Conference on ‘Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe’. Her paper is entitled: ‘The Garfagnana Model: exploitation of agricultural and cultural biodiversity for sustainable local development’. One of her prime examples will be Cerasa farm, a mountain paradise which is no secret to my clients who have written rapturously about their visits (here, here, here, and here May 2012). Mario, Gemma and their daughter Ombretta are a fundamental part of a project, overseen by the Germplasm Bank set up by the Comunità Montagna della Garfagnana (now the Unione dei Comuni), to preserve the indigenous Garfagnina Bianca sheep. If you’ve noticed some sheep lurking in the foreground of a nativity scene by Giotto, it could have been this breed, which was once common in the Apennine Mountains. Mario and the dogs look after the sheep. Gemma makes pecorino cheese and ricotta from their milk. Ombretta dyes their wool with natural dyes and has them knitted and woven into saleable products. Mario rears rams to sell to other farmers who want to join him in preserving the breed. Another strand of the Germplasm Bank project is the botanical station at Camporgiano. They have rescued dozens of indigenous varieties of fruit and vegetables. Besides being grown at the station, each variety has been entrusted to a custodian, a local farmer responsible for its propagation and preservation. I visited the station last year where the Director Dr Fabiana Fiorani explained their work. In 2013 the Garfagnana submitted several apple varieties to the European Pomological Exhibition at Limoges where it gained the distinction of ‘Custodian of Biodiversity’. Watch this space for the announcement that I can take you to the botanical station followed by a visit to one of the custodians and lunch in their home. The next opportunity to visit Cerasa is during the Cheese, Bread & Honey tour in June. The UNESCO conference lasts for three days, during which dozens of international experts deliver research papers. It could be a big yawn, but judging by some of the titles, I for one would be awake. For example, a paper by J. J. Boersma of Leiden University is intriguingly titled ‘Could the rewilding of Europe be seen as progress?’, with the implication that the answer is ‘yes’. To me the most interesting theme is that biodiversity of domesticated plants and animals appears closely connected to cultural diversity arising from the traditions and identity of a place. Finding the balance between tradition and modernity may be the virtuous path to sustainable rural development. The mere fact of an international conference organised by UNESCO on the topic of biodiversity and sustainable development raises hope that the planet will not be entirely subjugated to the interests of agri-business. A more local, but equally important action took place yesterday, also in Florence, when Slow Food organised a demonstration against the introduction of GM corn in Italy. Fingers crossed! Find out more: Joint Programme Between UNESCO and CBD, Convention on Biological Diversity, Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity in Europe Conference programme, Les Croqueurs de Pomme

*Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, based in Montreal, Canada By Gina Piazza and Heather Jarman One of the great pleasures of organising tours and courses is getting to know my clients. Often this happens during the initial phases of communication, even if people are booking a Small Group Tour or one of our Courses with Artisans for which the dates and programme are already fixed. People ask questions, I reply and we get to know each other. A wonderful example of this is the emails between Gina and me as she and her husband from California were preparing to come on the Advanced Salumi Course which is taking place right now. ME (during the previous course): The course is going well. We had a good day yesterday. But one man on this course is having problems understanding because he has never done any butchering and doesn’t know pig anatomy. This reminded me of you telling me that you didn’t have any butchering experience. I think you will get more out of the course if you at least do some reading up on the internet and maybe look at some diagrams of pig anatomy. GINA: I did help butcher a half hog just a few weeks ago!! I completely dissected the head and then helped saw it in half for roasting. I deboned the shoulder, cut rib chops, and trussed up a shoulder roast stuffed with garlic and herbs- it was fantastic!! After the course we bought an entire hog head and I made pig head pozole- I’ll send pics later but it took 2 days to complete and it was delicious! Had some friends over and made a party of it- See you in a few weeks! YAY! Ps…Is it raining a lot? ME: I’d never heard of pozole. Looked it up on the internet and got an ‘authentic’ recipe for pork shoulder and saying it takes 1 hour 45 minutes. Yours sounds much more authentic! Would love to see the photos. We’ve just had three whole days of sun!! GINA: We had to split the head in fourths to get it into 2 pots- Boiled it with herbs for 3.5 hours… …soaked hominy overnight then cooked all 2.5 pounds of it (dried white corn) for 3.5 hours, cut up 5 pounds of pork shoulder and boiled for 2 hours, then took 3 types of dried chilis and garlic charred them on an iron skillet, de-seed the chilis and soak the skins in hot water for 30 minutes. Blend garlic, chilis and chili water in a blender to make a paste that seasons the soup base. So you see, if I bought canned hominy, that would save time but taste horrible. I boiled and shredded the head one day… …and make everything else the next- the broth from the head is amazing!! We put some aside to add to both a ramen and a Cannellini bean soup- delicious. ME: Amazing!!! Your description and photos would be perfect as a guest blog on my blog. GINA: Let’s do it! AND, tonight I’m casing 20 pounds of farce for Sbriciolona salami to dry cure for 4 months- I’ll document that too. We’ve made Cotechino, Gaunciale, and Cacciatorini as well. ME: Great!! You’ll be able to teach the course by the time you arrive! GINA: The day began with lots of rain so it was a perfect time make salami! We didn’t even change from our pajamas! I prepared 20 pounds of pork leg and hog casing the night before, then proceeded to turn the casing inside out with the awesome trick of running the water through. I ground the pork to stuff into the 20 feet of hog casing for our final product of fifteen, 1 yard each Sbriciolona salami, that will air cure first for 4 days in the shed, then for four months in a temp and humidity controlled stripped out refrigerator. My husband, Kirby, also prepared 20 pounds of pork leg to make Cacciatori and spicy Italian sausage. I won’t bore you with the details of how we got to this point because in truth, our kitchen is small and tempers are short…..but, I’m still married and we poured a BIG glass of wine and toasted- to our salamis, that hopefully won’t crash down from the ceiling! THREE WEEKS LATER When Gina and Kirby arrived on the course we hugged and kissed on both cheeks like old friends! She’s excelling on the course. I’m eager to follow Gina and Kirby’s progress after the course, and I hope to visit them when I visit my sister in California.

As soon as Marzio saw my last blog ‘What Grandparents Ate‘, he phoned to tell me I’d got it all wrong. Picchiante aren’t pig’s lungs; my dictionary is correct: they’re cow’s lungs. Could be. Ismaele rears beef cattle as well, including the rare Pontremolese breed. I emailed Ismaele to find out what he’d given Marzio. The reply just arrived with a variant of the name picchiante: ‘Il picchiatello è di manzo’ (the lungs are beef).

Health warning: Vegetarians and hesitant carnivores may find this blog disturbing. At the end of the last Advanced Salumi Course I was chatting with the norcino (pork butcher) Ismaele Turri and my driver Marzio Paganelli outside Ismaele’s butchery. Marzio asked me whether I’d ever eaten picchiante. I’d never even heard the word, so I wasn’t sure. They’re lungs, he explained, and his grandmother used to make a delicious dish with them. Did I want to try them? I wasn’t sure, but thought I ought to in the name of research. Problem is, where could he get them? He hadn’t seen them at a butcher shop in years. Ismaele rears pigs, and when one is slaughtered, he gets the whole animal back from the abattoir—head to tail, skin, offal, bones and blood. Nothing missing. He led us into the cold room; I briefly saw something long, grey and smooth before he popped it in a plastic bag and handed it to Marzio. No money changed hands. We fixed Tuesday for the dinner. I phone Tuesday midday to check what time to arrive. Marzio is already in the kitchen. He says if it doesn’t come out well, we don’t have to eat it. I consider taking a pork chop. When I arrive at 8 pm, his wife Carla tells me she’d gone out for the day to avoid cramping his style. I’m relieved that there are good smells coming from the kitchen. Marzio loves to recount recipes as if they were stories. This is what gave me the idea of ‘Cooking with Babbo’. Babbo is the Tuscan equivalent of ‘dad’ or ‘pa’. I bring my guests to the Paganelli’s summer haunt, a renovated chapel on the ridge above their home in the valley, and we cook whatever Marzio feels like. No menu, no recipes. While a ragù simmers, he’ll grab a jug and lead you down to the spring below the house, or take you to the veg patch to pick tomatoes. Carla is there too, and steps in to teach her to-die-for tiramisu. As a rule I don’t approve of cooking lessons as the only introduction a traveller gets to our food. Tuscan cuisine relies above all on good primary ingredients, and you have to know where to find them and how much better the flavour is than industrial food. That’s why I take my guests to visit artisan farmers and producers. But ‘Cooking with Babbo’ is as much a lesson in the dynamics between Italian husbands and wives as a cooking lesson. It’s a cultural experience. This time Marzio lifts the lid to a simmering pot and shows me the deep, rich red sauce from which small brown cubes of meat protrude. The story begins. He chopped two onions and sautéed them for several minutes in extra virgin olive oil, pressed from his own olives. He had already prepared the lungs. That’s what took longest, because you have to remove all the tubes so the finished dish won’t be chewy. He added the cubed lungs to the onions along with a small clove of garlic and a pinch of peperoncino (chile pepper), and sautéed them for an ‘abundant 15 minutes’, splashed in some white wine and evaporated it (sfumare), added chopped, peeled tinned tomatoes (much better in winter than tasteless hothouse ones) and some tomato paste. Then some hot water (or vegetable stock) to cover. He put the lid on the pot and simmered it for ‘an abundant 50 minutes’. Time is often as important an ingredient as the physical ingredients. The recital over, the pot is brought to the table along with a platter of hot, fairly firm polenta which he has piled in a mound and decorated with a fork. Formenton otto file, he states. It’s the old variety of maize whose stoneground meal makes polenta that actually tastes like corn. He cuts a slice of polenta with a knife and struggles to carry it to my plate. His grandfather used a pliable willow branch, which was perfect for cutting the polenta and getting the slice to a plate in one fell swoop. Carla spoons the picchiante in umido, the lung stew, to the side of the polenta. We look at each other, exchange the ritual buon appetito, and taste it. I’d expected a slightly slimy texture, but the cubes of lung are resistant while not being tough and the flavour is deep and complex. Truly delicious! As we enjoy Marzio’s creation, we ponder the origin of the word ‘picchiante’. The Italian for ‘lung’ is ‘polmone’. Maybe it’s Tuscan. When I get home, I check my Italian-Italian dictionary compiled by two Tuscan scholars, Devoto and Oli. They confirm the word as 16th-century Tuscan, but say it refers to the lungs of a cow. Nevertheless, the Italians in my village know I’m talking about pig lungs when I tell them what I’ve eaten. It also means door knocker, and was applied to lungs because they lie near the heart. Marzio and Carla talk nostalgically about all the ingredients that have disappeared from shops and the dishes that no one makes anymore. They think young people don’t like them, and wouldn’t eat them even if their parents could be bothered to prepare them. Every year Carla’s family reared a pig which they slaughtered in January. Marzio and I chorus, ‘Il giorno di Sant’Antonio’, the 17th of January. Sant’Antonio is the patron saint of animals, and it always seems strange to me that this is the day of the slaughter, but Carla thinks he only protected young animals. Anyway, no part of the pig was wasted; there were traditional ways of eating or using everything. Not only every cut of an animal was used, but a large variety of wild and cultivated plants formed part of the daily diet. This is partly old people’s talk. We’re at that age when the world seems to be going to the dogs. But I’m cautiously optimistic. I see hopeful green shoots: farmers’ markets, artisan bakers and butchers, restaurants featuring liver, pigs’ feet and foraged plants. And Marzio is still making his grandmother’s picchiante in umido.

Participants on our Advanced Salumi Course taste a vast array of salami, prosciutto, capocollo, soppressata and other cured pork delicacies, some not so delicate. For dinner they get to try other typical dishes of the areas where the course takes place. On our first night we’re in Versilia, the northern coast of Tuscany. Gabriella Lazzarini, one of my cooking teachers and a skilled chef, lives here near Viareggio and invites us to her home for a seafood meal, which is one of the highlights of the course. Not only is it special eating in a private home, but Gabriella’s repertoire of local recipes is exceptional. She buys fish from the small family fishing boats called pescherecci that bring their catches to the molo (quai) in Viareggio. They fish off the rocks close to the coast, and the fish look strange to people who are used to seeing branzino (sea bass), orata (gilt-head bream), tuna and other large, usually farmed or endangered species served in most of the seafood restaurants here. You don’t have to enrol in the salumi course to eat at Gabriella’s home. All Sapori e Saperi Adventure’s guests can choose a meal with her as one of their activities. The other unique dining experience is on Saturday night after we’ve moved east over the Alpi Apuane to Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. We go to the Osteria Il Vecchio Mulino where our host is Andrea Bertucci, who is known affectionately as ‘Andreone’, which means ‘big Andrea’. You can see that the love of his life is food. But Andrea doesn’t cook; in fact, his osteria doesn’t even have a kitchen. Andrea is a food collector. He finds the best products in the Garfagnana, and sometimes further afield, which he serves as a tasting menu. The nearest analogy is a tapas bar, but his place is more like a hybrid of a corner grocery, wine bar and a cheese and salami maturing cellar. Since the menu depends on his latest finds, there are always surprises. In his tiny oven, not a microwave, he heats crostini and savoury tarts. There’s usually a salumi board, but I suspect we’ll be salumied-out on the course and ask him for alternatives. On a two-burner electric hot plate he warms up local specialities prepared by his mother or friends. This time it’s polenta formenton otto-file, an heirloom variety of corn, with roe deer ragù. Every time we thank Andrea and say we must leave, he produces another goodie: cinta senese salami, cured roe deer loin, fruit salad he made that very day, 15 February, which is San Faustino’s Day, the patron saint of singles. I’ve checked on Google and it’s true!

|

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed