|

What happened to Janet after indulging in artisan food in Tuscany? Here’s the unexpected answer in my latest post on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/life-changing/ Shortly after she returned home to California I received a WhatsApp message from her which began:

“You have ruined me!!!” I was worried, but not for long. Read the rest of my blog on the Slow Travel Tours website: http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/life-changing/

0 Comments

I’ve long wondered how to incorporate the rich agricultural heritage of the Lucca plain into a tour. Watching a bean stalk grow would try the patience even of a very slow traveller. On Thursday I visited the organic farm Favilla in the suburbs of Lucca, where I was welcomed by Andrea, the owner’s son. As he spoke about his farm and its crops, the words tumbled out of his mouth and his face was alive with the enthusiasm he and his family devote to their project. The list of crops is long leaving no season without its fruits: wheat, vegetables and fruit. To find out more about the small group tour germinating at Sapori e Saperi Adventures, read the rest of my blog at http://slowtraveltours.com/blog/a-tour-sprouts/. Read to the bottom of the blog and you’ll find a special offer.

Save the dates: 2–9 July 2017. In England when I used to prepare historical feasts for Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music, I pined futilely for a cardoon farmer. Cardoons cropped up regularly in recipes of the 17th and 18th centuries. I finally persuaded a friend to grow them on his allotment, but he planted them next to his artichokes, which are nearly identical, and couldn’t remember which was which. In culinary terms it matters; you eat the flower of an artichoke, but the stem of a cardoon. I can’t find any advice on what would happen if you ate the stem of an artichoke, and I didn’t try. Cardoons are common in Italian shops and markets from November to February. Although they are completely unrelated, they look like giant celery but surprise with a flavour of artichoke hearts. The heads come in two shapes, depending on how they’re grown: straight stalks which are called cardi, and curved ones called gobbi. Gobbo means ‘hunchback’, and touching an amulet of a gobbo is said to bring good fortune. Whichever the shape, the cultivation and preparation of cardoons is fiddly. During their last month in the field, the stems are blanched like celery, by piling up the earth or tying straw or paper around them so they lose their chlorophyl and become creamy white. If you’re growing them gobbo-style, you bend them in half before covering them with soil. In the kitchen you de-string them, cut them into chunks and boil them in acidulated water to keep them from rusting. They’re good eaten hot simply with a drizzle of this year’s extra-virgin olive oil. In the Abruzzo a traditional Christmas lunch begins with a soup of cardoons and meatballs. I’ve recently tried a Lucchese recipe for using up leftover bollito (boiled beef): infuse olive oil with garlic and sage leaves over a low heat, add chunks of boiled cardoons and sauté until they start to brown, add the boiled beef cut into cubes, stir well, deglaze the pan with white wine, add a few tinned tomatoes (not tasteless winter tomatoes) and simmer for 15 minutes. As long as you go light on the tomatoes, the flavours balance each other perfectly. Nutritionally cardoons are star players. They are said to have a fortifying and bracing effect on the stomach, protect the liver, reduce cholesterol and blood sugar levels. Who knows, maybe they’re the elixir of youth.

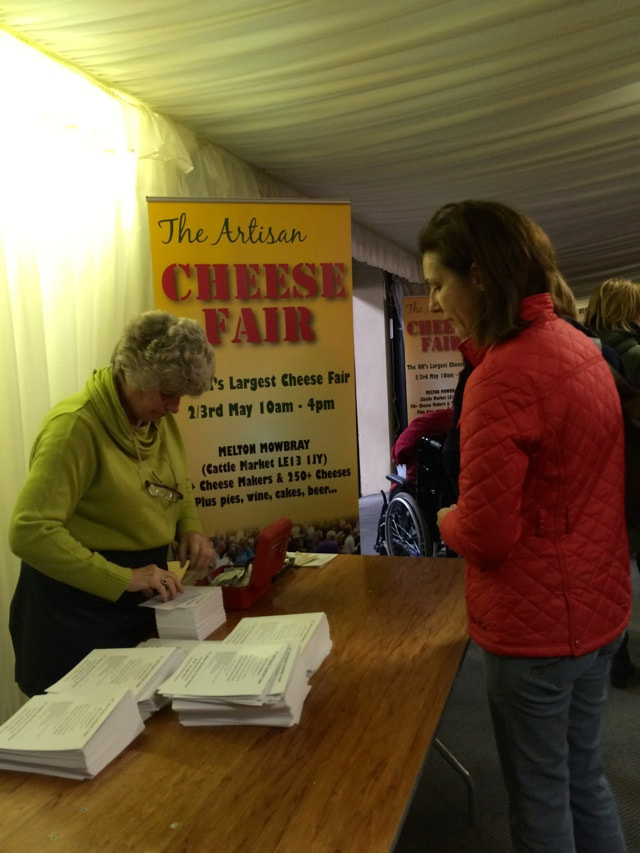

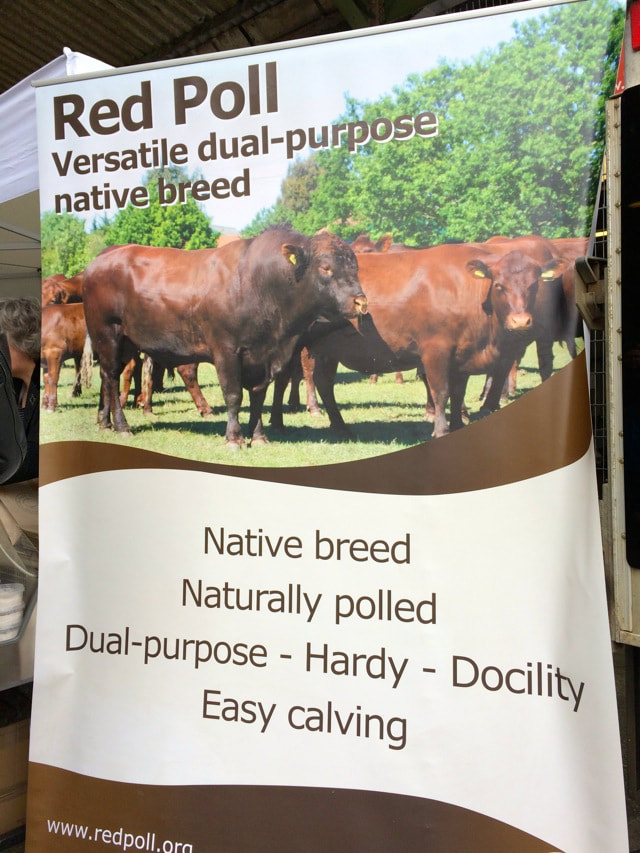

There’s an old variety called cardo gobbo of Nizza Monferrato from the province of Asti in Piedmont. Being on the brink of disappearance, Slow Food has recognised it as a presidium. It grows on sandy soil with no fertilisers, chemical treatments or irrigation. Sown in May, by September the tall luxuriant stalks are ready to be bent over and covered with soil. The Slow Food website describes the plant dramatically attempting to liberate itself to get to the light. In the process of its struggles, it swells up and turns pure white. Once harvested and cleaned, it’s the only cardoon that can be eaten raw, and is an indispensable ingredient of bagna cauda, the typical Piemontese warm sauce based on garlic, extra-virgin olive oil and anchovies. Continuing the purple prose, ‘It’s not merely a dish but a convivial ritual. Simmering in the centre of the table in an earthware terrine, the diners dip the pieces of vegetable and bring them to their mouths, catching the oil on a chunk of bread.’ If you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Nizza Monferrato right now. Postscript: Some ingredients draw me to repeated research. I had written this piece before discovering that I also wrote about cardoons in January 2013: http://www.sapori-e-saperi.com/seasonal-eating-4-cardoons-2/ At the end of my Theory & Practice of Italian Cheese course, I organise a little game: an England vs Italy sheep’s milk cheese tournament. This entails a trip back to the UK immediately before the course to go to Neal’s Yard Dairywhere I can always find a few excellent sheep cheeses. For the May course I did my shopping instead at the annual Artisan Cheese Fair at the old Cattle Market in Melton Mowbray. Although in its fifth year, I had never heard of it, but being featured by the Specialist Cheesemakers Association, I figured it would be worth the trip to Leicestershire, a direct train journey from Cambridge on the line to Birmingham, from where my friend Amanda joined me. It’s also one of the counties, along with Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, in which Stilton is allowed to be made. (Stilton, like Parmigiano Reggiano, is a registered product with a Protected Designation of Origin.) Unlike the market in Cambridge, which is today a ‘cattle market’ in name only, the one at Melton Mowbray still functions every Tuesday morning. I make a resolution to come back to witness the livestock auction. Turning to the entrance to the cheese fair opposite, we find the entrance fee is only £2 and admits you not only to the area populated with vendors’ stalls, but also to a series of cheese classes and tastings. The Red Poll Cattle Society was founded with the aim of preserving this versatile native breed. They note the long lactation period and ideal composition of the milk for cheesemaking. The British Isles are a land of cattle. Sheep these days are reared for meat, and it’s harder than I expected to find sheep’s milk cheese. These people from Canterbury can’t offer any. Amanda has served me excellent goat’s milk cheeses made by Pete Humphries of White Lake Cheeses in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, heart of cheddar country. At the far end of his stall, I glimpse a label saying ‘No Name Sheep Cheese’. He’s begun experimenting with sheep’s milk and this cheese is so new that he hasn’t come up with a name yet. It’s a bit young to compete with the mature pecorinos in the Italian team, but I hope it will make up in youthful energy for what it lacks in experience. Sharing a corner stall are two outstanding talents of British cheese, Jamie Montgomery who makes arguably the best cheddar in Britain, and Joe Schneider who makes Stichelton. Amanda and I found the farm on the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire for Joe and Randolph Hodgson of Neal’s Yard Dairy when they were setting up the dairy to produce what they expected to call ‘raw milk Stilton’, a return to how Stilton was made for centuries. However, due to an anomaly in the PDO definition of Stilton, it can only be made with pasteurised milk. One of the Dairy’s customers suggested Stichelton, an early name for the village of Stilton. Joe welcomed us to the stall and gave us a good chunk of this incomparable cheese to take home. Notice in the photo that the Stichelton isn’t excessively blue. The flavour of the blue mould doesn’t kill the flavour of the cheese. In search of two more sheep cheeses we crossed to another pavilion, passing a ukulele band and an artful display of Quickes Traditional Cheddar. Right at the entrance was the stall I needed. Carlow Farmhouse Cheese had brought several mature sheep’s milk cheeses to the fair. They don’t have their own website, and this one only admits to cow’s milk cheese. Their cheesemaker, Nadja, guided us through her samples. It was hard to choose, but I finally took some ‘pecorino-style’ and ‘cheddar-style’. Business done, we threaded our way through the crowds to a promising-looking pork pie stall. The pies were obviously raised by hand. The pastry is made by mixing hot melted lard with flour. It has to be exactly the right temperature to form it around the wooden moulds (see photo above)—not so hot that it burns your hands and not so cold that it cracks. The baker himself sells us our pie. He reminds me of my Italian artisan food producers when he talks about the natural ingredients he uses: the flour from a nearby windmill, pigs from a local farm and pig’s-foot jelly he makes himself. He’s sold 300 pies this morning and will be off soon to make another 300 for the next day’s fair. With a glass of incredibly strong cider, we settle down to lunch. I used to make pork pies myself, but these pies beat even my best. The crust was crunchy, the filling tasted like pork (not overpowered by spices and preservatives) and the jelly was well seasoned and firm without being rubbery. Melton Mowbray is a pretty market town, but even without its other attractions, it would be worth a pilgrimage for the King’s Road Bakery pork pies alone.

Italy is usually the clear winner of the pecorino match, but this time Ireland came out top in the opinion of our maestro Giancarlo Russo, a judge in international cheese competitions. Young ‘No Name’ was a big hit too with several of the course participants. A guest blog by Bob Schroeder Bob, his brother Dick and their friend Cullen Case came on my Advanced Salumi Course. They wanted to make the most of their visit and signed up for a truffle hunt on the Tuesday afternoon after the extension workshop. Bob gave me permission to republish his enthusiastic report to his family and friends back in the States. January 20, 2015 We went truffle hunting today. Lots of fun. Our guide actually trains dogs. He took Guy Fieri of Food Network fame on a hunt. Thanks, Bob!

In case you don’t know, truffles can be found all year long. Although the white Italian and black Périgord truffles are the stars, they’re all good and well worth tasting. We have seven edible ones in Tuscany. After the hunt, we go back to Riccardo’s home for a truffle feast cooked by his wife Amanda. We sit in their kitchen sipping prosecco with the antipasti and get to be part of the family. Just back from my annual visit to family and friends in Los Angeles, Costa Mesa and Santa Barbara. It was a foodie time. Not least because my sister Gai Klass, before she retired, was top caterer in LA (according to me and the Zagat Guide); my 3-year-old great-nephews are following in the family tradition; my friends in Costa Mesa came on my Advanced Salumi Course last year and are ace picklers, aficionados of Mexican cuisine and blossoming norcini(curers of pork); my friend in Santa Barbara is a private chef (who did a personalised tour with me several years ago); and the rest are great cooks and lovers of good food. I report the latest trends. Armies of pigs have invaded delis, restaurants and antique shops. Everywhere I went pork, from ears to ribs to tails, was on the menu. As expected wine held sway even in the loos in the Santa Ynez Valley, best known for its Pinot Noir. But craft beer was running a close second (as it does now in Italy)… …and came first on Main St, Venice (CA) …and in Carpinteria. Sardinians on Main St, Santa Monica, produce one of Italy’s best exports. And everyone was getting on the buy local and gluten-free band-wagons. In case you’re in the area, I’m sure they’d all love to see you:

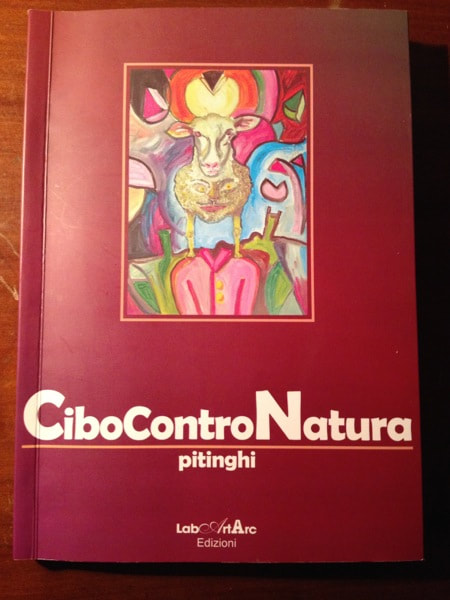

Bacon & Brine, Solvang http://www.baconandbrine.com/ Angels Antiques, 4846 Carpinteria Avenue, Carpinteria, DolceNero, 2400 Main Street, Santa Monica http://www.dolcenerogelato.com/ For a dinner that was so good that I forgot to take a photo: Barbareño, 205 W Cañon Perdido Street, Santa Barbara http://barbareno.com/ PS The next generation gets a head start in the kitchen. The first year I went to the International Truffle Fair at San Miniato one of the sideshows was a small bookstall. A woman thrust a book into my hands and explained exasperatedly, as she touched a finger to her head, that it had been written by her loopy husband. Perhaps he had insisted she listen as he declaimed each of its 121 pages. As I read the polemical Cibo Contro Natura (Unnatural Food) I could hear Signor Pitinghi shouting his manifesto while gesticulating with his hands. The flowery language can be over the top, but far from being mad, it’s full of insights into a passing Italian food culture. This is a frustrated man with the memory of a flavour in his mouth which he finds harder and harder to reproduce in the kitchen. Perhaps his wife is a bad cook, but this isn’t what he laments. He’s dismayed by the swamping of natural food by industrial food, of slow food by fast food, of real cooking by virtual cooking, of found ingredients by packaged and marketed products. Having read a chapter or two, the book itself got swamped by other literature I picked up at other food fairs and only re-emerged recently. My experience of Italian culture, not to mention my comprehension of the Italian language, has grown in the intervening years and many of Signor Pitinghi’s ideas set me thinking and exploring half-trodden paths. Among his many provocative statements is the chapter title ‘Bisogna provare a cucinare o almeno…a cuocere’, which translates literally: ‘It is necessary to try to cook or at least…to cook’. The dilemma for me is one of linguistics and culture; for him it’s one of action. I check my excellent Italian-English dictionary by Ragazzini and Biagi just to make sure both cucinareand cuocere mean ‘to cook’. They do, but there’s a hint of a difference. Cucinare can also mean ‘to do the cooking’. My Italian friends sometimes correct me for using one or the other incorrectly, but I haven’t quite got it yet. Back in San Miniato having lunch with Riccardo and Amanda, my truffle hunter and his wife, I ask them if they can enlighten me. We’re eating a typical Tuscan lunch, a simple roast chicken with potatoes and onions. Amanda explains that if she had bunged the chicken into a roasting pan and stuck it in the oven until it was done, that would be cuocere. Instead, she had seasoned the chicken, browned it in olive oil, deglazed the pan with white wine, put it in the oven and basted it from time to time. She’d cut up the potatoes and onions and added them to the roasting pan to cook and become glazed by the juices of the chicken. All very simple yet this is cucinare. Now I could transfer it to my own culture: ‘I can boil an egg, but I can’t cook’. Pitinghi reminds his Tuscan readers how simple their cuisine is and muses on whether in our ‘global village’, with mother at work and incessant television cooking programmes interleaved with adverts for snacks full of preservatives and breaded fish fingers ready for frying, the family no longer knows how to keep traditions alive, especially those of cooking and local food. He ends with this exhortation ‘to all of us: “let’s try to cucinare!” or at least, if this verb seems too challenging “let’s try at least to cuocere something”.’

Christopher Hogwood died on 24 September at the young age of 73. Although he will be remembered first and foremost for his contributions to music, his interests were wide-ranging. High on the list was dining. He understood perfectly that a convivial meal could bring friends closer together and facilitate business meetings. When asked to name a time for a meeting, there were only two answers: ‘Lunch’ and ‘Dinner’.

Christopher wasn’t a cook. His idea of cooking was to mix three different flavours of Waitrose’s soup-in-a-box. This suited me perfectly. During the quarter century that I was his personal manager and editor of the introductions to his many musicological publications, I also had the unofficial position as head chef in his Cambridge household. My first career having been in archaeology, we shared a common respect for the past. We both enjoyed the search for how ‘they’ did it ‘then’. This must have been what led us to the idea of historical feasts. In the late ‘70s the Academy of Ancient Music performed at least one concert in each of the annual Cambridge Summer Music Festivals. One year we decided to throw a post-concert garden party at Christopher’s house. The menu would consist of dishes of the same period and nationality as the music in the concert. It must have been Purcell that year. I headed to the Cambridge University Library and found only a paltry collection of antique cookery books. Among them was Robert May’s The Accomplisht Cook published in 1660. I was a novice to interpreting historical recipes, and I’m sure I made more mistakes than the musicians in their interpretation of the notes on the page. Spectacle and bravura were all, as in pageants of the day. I invited many people to contribute. I remember especially a spectacular fortress of a raised pork pie complete with crenelations constructed by Christopher’s keyboard restorer Chris Nobbs. No feast is complete without wine. Christopher had an excellent cellar, but it didn’t contain bottles of 17th-century English wine. We found a good substitute in English wine from nearby Gamlingay. Christopher’s personal library now began to swell with 17th and 18th-century cookery books. From then on the feasts became ever more historically informed. We started from the premise that people who were capable of appreciating sublime art and music, wouldn’t have tolerated the foul tasting food that historians claimed they put on their tables. Our assumption proved correct. Everything I made from those historical cookery books was excellent, without any modernisation. The next step should have been cooking with original instruments. Maybe if I hadn’t left in 2004 to found Sapori e Saperi Adventures — Flavours and Knowledge of Italian Artisans, we would have built a wood-fired oven, reopened the dining room fireplace and installed a spit for roasting mutton. After I left, he started an occasional restaurant guide aimed at musicians who so often find themselves performing in unknown cities and in need of a good meal: http://www.hogwood.org/archive/food-counter/ I shall be ever grateful to Christopher for his support and faith in me as a cook and interpreter of historically informed cuisine. ‘Garfagnana Dove Il Tempo Non Corre’ is the motto printed on aprons sold by the tourist office in Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. It means literally, ‘Garfagnana where time doesn’t run’. We might say, ‘where time stands still’. In fact, it creeps along slowly. I’ve just reread a piece by Rebecca Solnit in the London Review of Books (29 August 2013) in which she reflects on some of the effects our electronic age have had on our experience of time: the interruptions to our concentration, the fragmentation of our solitude and relationships. She wonders how far we will allow big corporations to shatter our lives. Will we all be wearing Google glasses with continuous pop-up messages reminding us of practicalities while causing us to forget to ‘contemplate the essential mysteries of the universe and the oneness of things’? Then she muses: ‘I wonder sometimes if there will be a revolt against the quality of time the new technologies have brought us… Or perhaps there already has been, in a small, quiet way. The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn’t food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn’t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes and labour, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken.’ Reading this I realise it’s that wholeness I see in the producers to whom I take my clients: an immersion and satisfaction in what they do. It’s not that they don’t have to work hard or that they don’t have troubles, but that doing something from start to finish, from sowing to harvest, from slaughter to salami, from fibre to fabric, for themselves, their families and their communities produces a contentment way beyond the monetary value of their work. I can think of so many examples it’s hard to know where to start or stop. …in a wood-fired oven he built himself heated with wood he chopped himself. He didn’t grow the wheat, but he does grow farro and corn. The farm is an agriturismo which he and his wife Cinzia run. And he has a bar a short walk from the farm. Paolo Magazzini is another unhurried multi-tasker. He’s a farro and beef cattle farmer. He fertilises his fields with the manure of the cattle. He ploughs, plants with his own seed corn, harvests and pearls the farro. He provides the pearling service for about a dozen other farmers. Paolo is also the village baker, carrying on his mother’s trade. His recipe includes his farro flour and his own potatoes. From her smile, I wonder if she’s thinking about the beautiful finished articles he weaves. Schoolchildren come to her workshop to learn about the history of their families and Lucca in the silk trade. Gino will carry the business forward with a smile into the next generation. What more could any parent hope for? …in his forge powered only by water. It takes considerable inner fortitude to resist the health and safety inspectors who want her to use stainless steel. Andrea is never short of time when he can spend it with customers who he feeds with his latest artisan food finds. He dreams up new recipes when he comes to check his beer in the middle of the night. …and the long hours he spends in the woods with his dog infuse his family and work life too. The wholeness of my producers’ lives floods over to envelop my driver Andrea Paganelli and me.

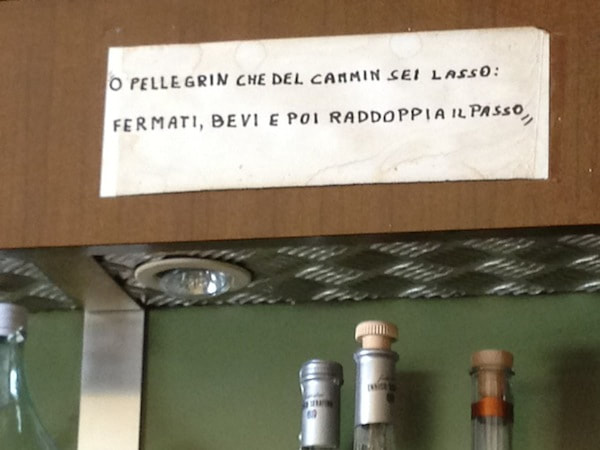

A couple of Thursday evenings ago I wrote a to-do list for Friday. The first item on the list was to pick up some leaflets at Topo Gigio, the bar-trattoria in Fabbriche di Casabasciana, the village at the bottom of my hill. The leaflets advertised a concert on Sunday for the benefit of the centre for the elderly at Casabasciana, which I was helping to organise. Considering the length of my list, all the things I wanted to get done before the weekend, the sensible thing would have been to hop in my car and drive the 3.8 km (2.4 mi). But it was a warm, not too hot, sunny day, and I hadn’t walked the mulattiera in ages. People in the village used to walk down it to school or work and back up again at lunch time every day. It seemed a bit feeble not to do it. I strapped my pennato lucchese, a Lucca-style billhook, around my waist and invited my friend Penny to accompany me with her secateurs. Mulattiera translates as ‘mule track’, but this makes it sound a paltry dirt path. In fact, the mulattiere (plural) were the super highways of the past, often many metres wide, surfaced in rounded cobbles or flat paving slabs, with stone-lined drainage channels at the sides or down the centre. Where necessary they were stepped. In mountainous areas like mine, they ran along ridges, usually just below the crest. Although they frequently crossed streams and small rivers, it was at the top where the water course was narrow and presented no great obstacle even in the rainy season. They descended to the valleys of major rivers only where absolutely necessary to arrive at a destination on the other side of the river. I’m not sure how old the roads in the Garfagnana are. It’s known that the Roman Consul M Claudio Marcello had the Via Claudia or Clodia Nova built in the 2nd century AD, and it’s likely that it followed an Etruscan road and possibly even earlier routes. The mulattiera that links Casabasciana with the valley is said to be mediaeval, but that’s the date people always attach to anything old. It’s about 4 metres wide and forms the main street in the village, descends about 100 m below the village and splits in two, the left fork diving steeply down to the pieve, the old romanesque parish church, and then continues to Sala, a hamlet of about 15 houses, which is linked by another mulattiera to the Liegora River which runs into the Lima River to the right. The other branch carries on straight down to the Lima, along which Fabbriche di Casabasciana is strung out. I’ve learned from my neighbours that upkeep of the mulattiera was the responsibility of each family through whose property it passed. In the ’60s the present-day car road was built, and since then the mulattiera has been used less and less by the locals. Only the sections used by woodsmen, hunters of wild mushrooms and wild boar, and horse riders (mostly tourists) are now maintained, and even these denizens of the forest tend to favour newer dirt roads suitable for 4×4 vehicles. It’s to us stranieri, who arrive with the notion of nature as a setting for recreation instead of work, that the task of cleaning the mulattiere now falls. Penny and I set off at about 9.30. We hacked, slashed and clipped our way to the bottom by around noon. Some parts of the road had been cleared but others were thick with elder and acacia saplings intertwined with clematis (old man’s beard) and brambles. It was particularly galling to find that one household had cut their land down to within a metre of the mulattiera and hadn’t been civic-minded enough to cut that stretch of the mulattiera as well. At Topo Gigio, arms scratched and bleeding, we bragged about our feat to the men playing cards or arriving for lunch, and taunted them by asking where they had been when needed. ‘O pilgrim, weary of your journey: stop, drink and then redouble your pace.’ Restored by the excellent worker’s lunch, I collected the leaflets and we set off back up the mulattiera. Even though uphill, it was much easier going this time.

If anyone knows of a volunteer work group skilled at repairing cobbled roads, please get in touch with me at [email protected]. They’ll receive warm hospitality at Casabasciana. |

Email Subscription

Click to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. AuthorErica Jarman Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

|

copyright 2017 sapori-e-saperi.com | all rights reserved

|

Website by Reata Strickland Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed